Finsbury Park attack: Roses for Ramadan worshippers

- Published

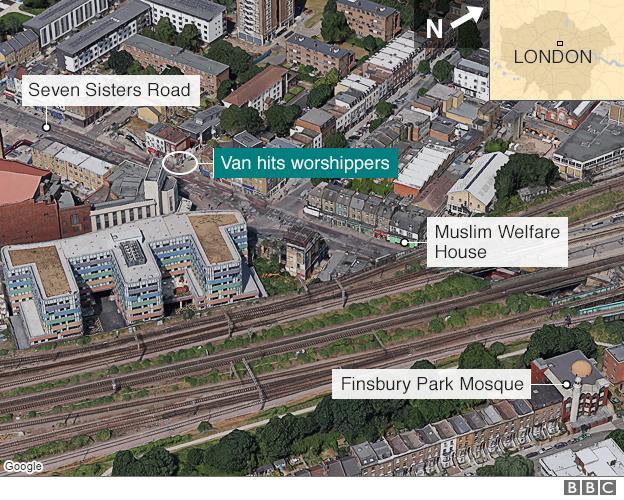

Journalist Lipika Pelham lives close to the Finsbury Park mosque, is a member of the local synagogue, and is accustomed to seeing girls in hijabs acting in the Nativity Play at her children's school. On Monday evening, nearly 24 hours after the van attack a few yards away, she was one of hundreds handing flowers to Muslim worshippers as they entered the mosque to pray.

A sea of roses - pink, yellow, white and red - symbolised multicultural London. People's faces were glowing in the evening sun. These non-Muslims, mostly from the area, were offering roses to Muslim worshippers.

A man in a Muslim skullcap and long white robe accepted a bouquet from a young Londoner in shorts and a sleeveless top.

I stopped an Orthodox Jew in a black hat, Hananja Fisher, and asked him what brought him there. He pointed to his eyes.

"My tears. This is all too familiar to us Jews, such attacks."

I had received a message telling me about the rose-giving event from my female rabbi, Shulamit Ambalu, as I was talking to a Somali neighbour who had been in the mosque when the attack took place.

Muhubo Barre always struck me as an extraordinary woman, raising 10 children in London, with a husband often away on business in Somalia. Her girls, wearing long Muslim robes and hijabs, would whizz past my house on scooters and bicycles on the way to school.

Muhubo had been at the mosque when the attack occurred, during a break after the first prayer session. People poured out on to the street, but the imam - who went on to stop the crowd beating up the alleged attacker - urged them back inside, in case other assailants appeared.

She went in and prayed that her older sons, who are 24 and 21, were safe. She heard that Salah, a friend of the family whose child is in year one at the local primary school where her younger children are pupils, was among those seriously injured.

"We finished the second prayer very quickly," she says. "I walked home at 2:10am on my own. I was advised not to, but I wasn't afraid. Why should I be? The attacker has no community, he's a lone crazy man, whereas I have one."

By "community" she meant not only fellow Muslims, but neighbours like me, a British Bengali married to a white British man.

Muhubo arrived in the UK in the 1990s from the autonomous region of Jubaland in south Somalia, as it became engulfed by a civil war which would leave Islamist militants largely in control.

She acknowledges that the Finsbury Park mosque went through "difficult times" under the radical cleric, Abu Hamza, from 1997 to 2004, but says tensions have evaporated in recent years.

On Saturday a "More in common" event was held at the Muslim Welfare House to commemorate the death of the MP Jo Cox, who in her maiden speech to Parliament famously said of her Batley and Spen constituency: "We are far more united and have far more in common with each other than things that divide us."

This applies just as well to Finsbury Park.

Last weekend Rabbi Shulamit was a guest at the mosque for Iftar, the breaking of the fast after nightfall during Ramadan. She found that she was simply able to walk in, without passing through any security checks - which are now routine at British synagogues.

Rabbi Shulamit Ambalu, pictured recently with other faith leaders near London Bridge

The imam initially assumed she was a Muslim worshipper, and invited to join the other women downstairs - she was amused, because the same would happen at any Orthodox synagogue. Then he realised his mistake and invited her to join him at the multi-faith Iftar.

When she left the mosque she walked out into a warm summer night, just as large numbers of worshippers were arriving to pray.

"It felt like Jerusalem," she says.

"That sense of anticipation, holiness, the excitement of a festival night. The sense of the closeness and also the differences between us, and how at times that very junction of similarity and difference can be so creative and also so uncertain. I simply felt at home."

I remember all too well the times when Finsbury Park would be in the news, if not for football hooliganism spreading out from Arsenal's stadium, then for the extremism preached by Abu Hamza.

In 1998, I sent a frivolous invitation to a party at our house to two of Abu Hamza's henchmen, including Omar Bakri Mohammed, who went on to head the al-Qaeda-affiliated group, al-Muhajiroun.

I never imagined that they would ring my doorbell.

I opened the door in my short dress with a glass of champagne, which I offered to the men. Omar Bakri Mohammed declined both the champagne and my outstretched hand.

We had a chat in the hallway. The men never ventured into my living room, possibly because people were dancing there. When they left, after about 20 minutes, I explained who the two guests had been - sending a shockwave through the party.

Things have come such a long way since then.

When I asked Muhubo Barre's eldest son, Ayub, 24, about Sunday night's attack, he said it had taken him a while to grasp that it could have been racially or religiously motivated. The idea seemed so strange.

"I didn't feel being Muslim in Finsbury Park, in London, was ever an issue," he said. "I believe as a community we'll get through this."

Despite the recent tragic events - Manchester, London Bridge, Finsbury Park - I left the roses ceremony in an upbeat mood.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.