Does the world need polymaths?

- Published

Two hundred years ago, it was still possible for one person to be a leader in several different fields of inquiry. Today that is no longer the case. So is there a role in today's world for the polymath - someone who knows a lot about a lot of things?

"The winner of the 1964 Nobel Prize winner in chemistry, which British X-Ray crystallographer was instrumental in…"

"Man produces evil as a bee produces honey. These are the words of which Nobel laureate, born in Cornwall in 1911, his novels include Pincher Martin, the Inheritors and Rites of…"

Obviously you don't need to hear the rest of these questions to know the answers. At least, not if you're Eric Monkman or Bobby Seagull. Seagull's fist-pumping and natty dressing, and Monkman's furrowed brow, flashing teeth, contorted facial expressions and vocal delivery - like a fog horn with a hangover - made these two young men the stars of the last University Challenge competition.

"Wolfson, Monkman" and "Emmanuel, Seagull" became familiar phrases, Monkmania became a hashtag. They squared off as opposing captains in the semi-finals (though in the final itself, the team from Balliol College, Oxford triumphed).

At Cambridge, Monkman and Seagull forged a most unlikely friendship. The Canadian, Eric Monkman, is the middle-class son of two doctors. Bobby Seagull's family originate in Kerala, India, and he was raised in a working-class part of east London, before gaining a scholarship to Britain's most elite private school, Eton. "If I got married tomorrow, I'd ask Eric to be my best man," says Seagull.

Find out more

Listen to Monkman and Seagull's Polymathic Adventure on BBC Radio 4 at 20:30 on Monday 21 August

They're still recognised in the street. "People often ask me, do you intimidate people with your knowledge," says Monkman. "But the opposite is the case. I have wide knowledge but no deep expertise. I am intimidated by experts." Seagull, like Monkman, feels an intense pressure to specialise. They regard themselves as Jacks-of-all-Trades, without being master of one. "When I was young what I really wanted to do was know a lot about a lot," says Monkman. "Now I feel that if I want to make a novel contribution to society I need to know a great deal about one tiny thing."

The belief that researchers need to specialise goes back at least two centuries. From the beginning of the 19th Century, research has primarily been the preserve of universities. Ever since, says Stefan Collini, Professor of Intellectual History and English Literature at Cambridge University, researchers have labels attached to them. "They're professor of this or that, and you get a much more self-conscious sense of the institutional divides between domains of knowledge."

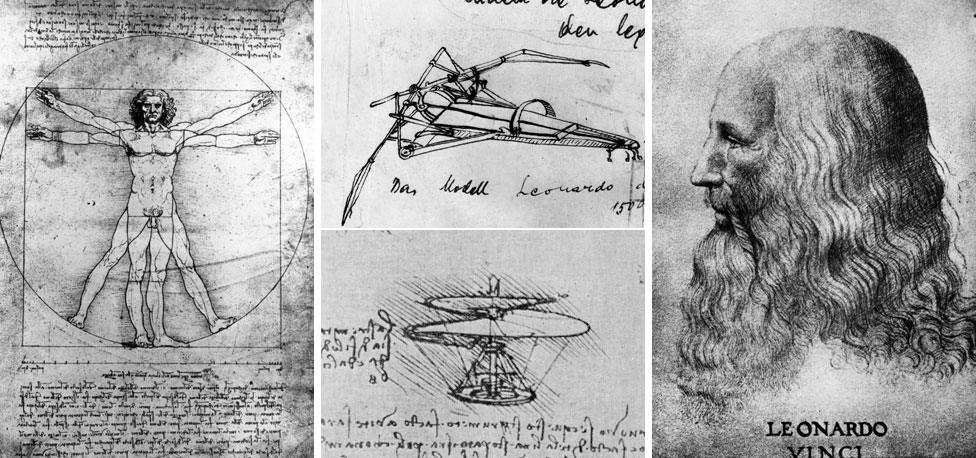

Before then, there were some polymaths who made original contributions in multiple areas. The word polymath stems from the Greek, polus, meaning "much" or "many" and mathe, meaning "learning". The first use of the word has been traced to the 17th Century. From the Renaissance, people such as Leonardo da Vinci - painter, sculptor, architect, physicist, anatomist, philosopher, geologist and biologist - gave rise to a synonym of polymath, the "Renaissance man".

Leonardo da Vinci designed an aeroplane and a helicopter-like "helical air screw"

One polymath/Renaissance Man was Thomas Young (1773-1829), the subject of a biography by Andrew Robinson entitled The Last Man Who Knew Everything. Young was a physician and physicist, whose achievements were breathtaking. He established the wave theory of light, undertook pioneering work in optics and studied 400 languages, helped decode the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone - and much, much more. And to confound any notion that he was a sort of 19th Century uber-geek, he was also an accomplished dancer and gymnast.

These days, any ambition to contribute to many disciplines is probably unrealistic. It takes years of immersion just to reach the boundary of our current knowledge in any one area. Today's polymaths might share the same personal qualities as Thomas Young - an abundance of grey matter, of course, combined with relentless curiosity and a tendency to workaholicism (Young barely slept) - but they are repositories of scholarship rather than contributors to it.

Monkman and Seagull's selected polymaths

Eric's choice:

Stephen Leacock (1869-1944): Anglo-Canadian political scientist and economist famous in Canada today for his collections of humorous essays and stories. The subjects of his comedy include academia, mathematics, life in rural Canada and the "leisure classes" described by his mentor Thorstein Veblen. When browsing a bookshelf in Canada, I always hope to find an early Stephen Leacock collection.

Joseph Needham (1900-1995): British biochemist, sinologist and historian. As a biochemist, Needham studied chemical embryology. As a sinologist, he was one of the first Westerners to realise the depth of Chinese accomplishments in science. This led him to pose the "Needham Question", asking why modern science arose in Europe but not in China. I find this an intriguing mystery.

Bobby's choice:

Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179): This German Benedictine abbess was a theologian, writer, poet, composer, artist, linguist, medical researcher and botanist. She is regarded as the founder of scientific natural history in Germany and is one of the first historically identifiable composers in Western music. I was taught about her during my years at St Bonaventure's Catholic secondary school.

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941): The Calcutta-born "Bard of Bengal" was the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize for Literature (1913). India chose one of his musical compositions for its national anthem, while Bangladesh chose one of his poems. He was also a painter, and founded the renowned Visva-Bharati University. My father, who studied Bengali literature at university, introduced me to Tagore at a young age.

So is there still a useful role for today's clever-clog - besides ringer in the pub quiz team?

Stefan Collini says that in many Western societies "there is a populist hostility to expertise in public life". It may be that polymaths, with their broader gaze, have an important role in communicating specialist fields. What's more, with ever narrowing specialism there is a need for generalists to synthesise information, to make connections between the discipline silos.

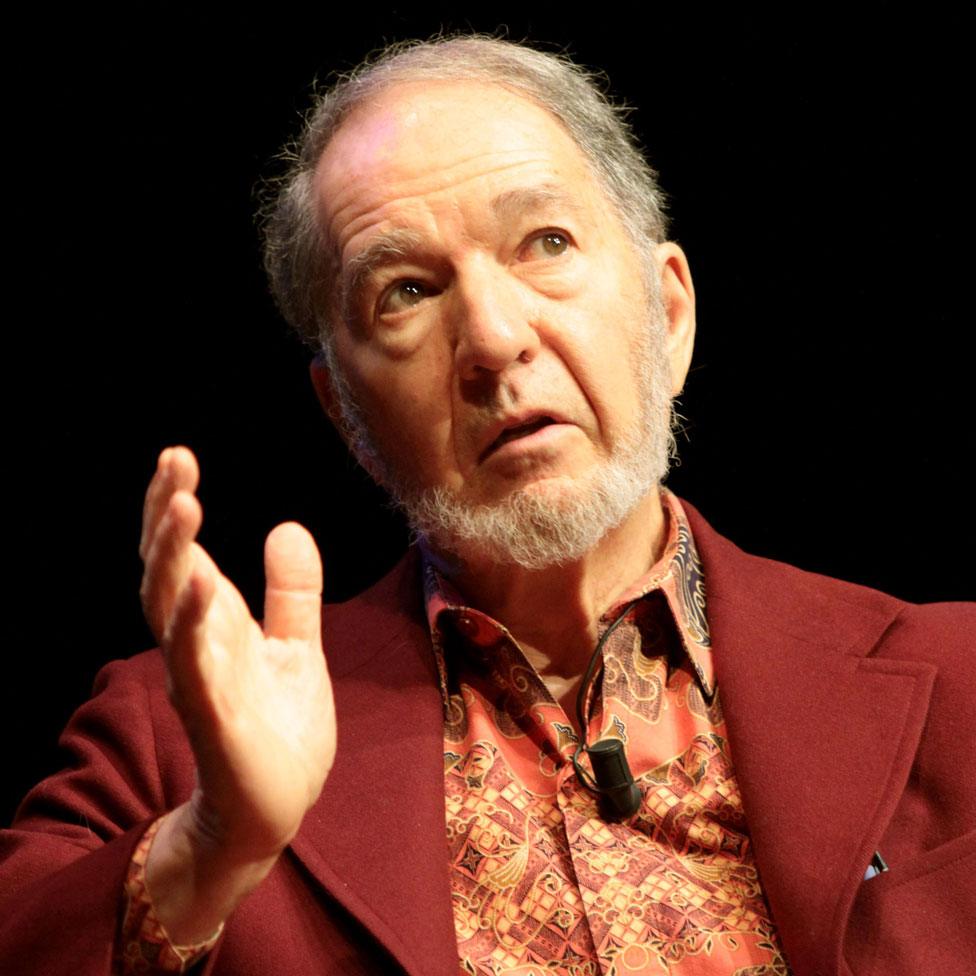

A contemporary polymath, the American academic Jared Diamond, drew on his interest in geography, evolution, anthropology, history and botany, to develop a theory explaining how it was that Eurasian and North African civilisations came to conquer others. It was turned into a best-selling book, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies.

Jared Diamond: One of Stephen Fry's favourite polymaths

Diamond is one of Stephen Fry's favourite polymaths. Fry - actor, comedian, writer and general egghead - is himself on the polymathic spectrum. He says he shares a personality trait with other polymaths - inquisitiveness. "If you know a lot, it's because you're curious," he says. "You have this impulse to know and, therefore, things stick to you. You put on, as it were, epistemological weight. I have always been fantastically greedy to know things."

Monkman and Seagull love knowing a lot of stuff. You might find them reading about the French Revolution one day, and about genetics or astronomy the next. Despite their anxiety about spreading themselves too thin, they share Fry's appetite to know. It's an overwhelming craving, likely to frustrate any countervailing drive to master one topic.

By the way. The answer to those two questions. Dorothy Hodgkin was the crystallographer, and William Golding the novelist. But you knew that anyway.

David Edmonds (@DavidEdmonds100, external) is the producer of Monkman and Seagull's Polymathic Adventure, on Radio 4 at 20:30 on 21 August.