Independence: Do Indians care about the British any more?

- Published

Seventy years since India gained its independence from the British Empire, the UK is seeking a closer trading relationship. But what do modern Indians think about the British?

I have an intimate family connection to the independence movement in India.

It is not something I normally talk about because it is nothing to be proud of - quite the opposite.

But as India celebrates 70 years of independence, this personal link has got me thinking about India's complex and often contradictory attitudes to Britain.

What India thinks of us is arguably more important now than ever before, given how much the British government is pinning on our future relationship with this vast and increasingly mighty nation.

Theresa May chose India as her first major overseas visit as prime minister very deliberately. As Britain looks towards its post-Brexit future, it is reaching out to India for support.

The prime minister hopes that refreshing the UK's trading ties with our former colony can form a major part of the country's new global economic strategy.

But India's response to her overtures has been distinctly tepid, and perhaps with good reason.

British-era buildings still dominate some parts of New Delhi

It has just rained when I drop in on the diplomat and MP Shashi Tharoor at his large, whitewashed colonial bungalow in South Delhi.

Insects throb in the humid evening and Delhi's incessant traffic roars in the distance.

I'm led through the dripping garden to the former under-secretary general of the United Nations' book-lined study, where he greets me with a warm smile.

He happily acknowledges that the legacy of British rule here in India has helped shape the attitudes and tastes of the tens of millions of English-speaking Indians.

"So much of what we take for granted in our daily life - the books we read, the way we eat, sometimes the way we dress, our habits and cultural allusions - have come from colonialism, British institutions and the English language," he tells me.

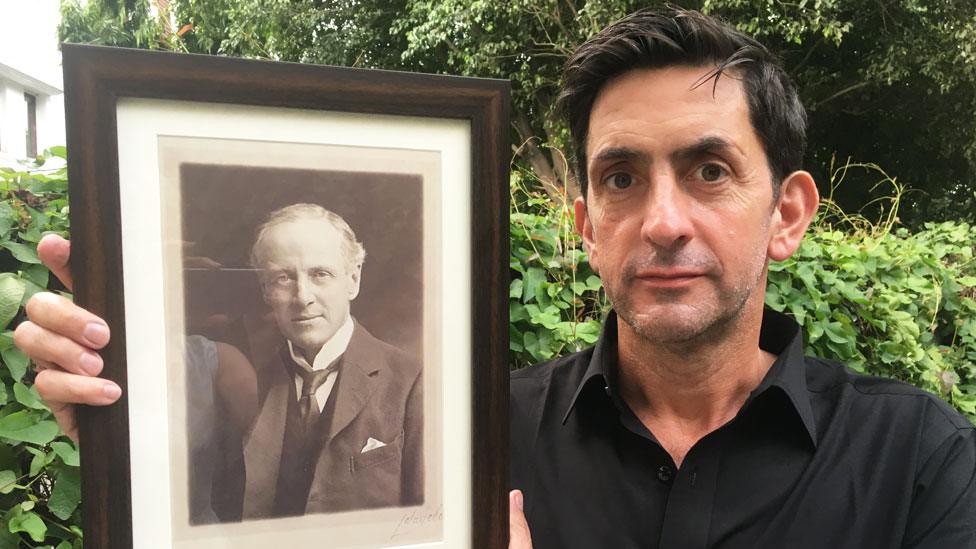

Justin Rowlatt holds a picture of his great-grandfather Sidney Rowlatt

"Most Indian nationalists used to enjoy reading PG Wodehouse - loved playing and following the game [of] cricket, for example.

"In fact, cricket - and beating the British at cricket - became a great trope of Indian nationalism," he laughs mischievously.

He even praises Britain for introducing India to the delights of tea - "now our national drink, to all intents and purposes".

Yet Shashi Tharoor is perhaps the most vocal and potent critic of Britain's imperial legacy around today.

A speech he made at the Oxford Union in 2015 demanding Britain atone for its wrongs in India became a social media sensation.

It has been viewed more than four million times online, prompted a wide debate in the British and Indian media and even earned him the praise of a political enemy - the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi.

The impact of his address persuaded him to write a book, published earlier this year, and - in Britain - called Inglorious Empire.

He felt compelled to write it, he says, because of the "moral urgency of explaining to today's Indians why colonialism was the horror it turned out to be".

The Victoria Memorial in Kolkata is another relic of the the colonial days

There's no doubt that there is anger and resentment in India at the indignities and brutality of empire.

But the truth is few Indians appear to bear grudges against the British today.

I should know, because a draconian law written by, and named after, my great-grandfather was the cause of one of the most notorious atrocities in British colonial history.

The law was known as the Rowlatt Act and led directly to the appalling massacre at Amritsar on 13 April 1919.

Gandhi, then a rather marginal figure among India's nationalist leaders, launched his first "satyagraha" - campaign of non-violence - in protest at the Rowlatt Act.

Sidney Rowlatt's law was immensely unpopular in India

The law suspended basic civil liberties for those suspected of plotting against the Empire and meant you could be imprisoned without trial for up to two years simply for having a seditious newspaper.

That is why thousands of Indians were in the walled garden of Jallianwala Bagh that day. Urged by Gandhi, they were there to express their disgust and fury at the legislation my great-grandfather, Sidney Rowlatt, had authored.

Almost a century on, it is worth remembering just how shameful the events at Amritsar were.

I went to the scene of the massacre for the first time last week. It was one of the most moving experiences of my life.

Sukumar "SK" Mukherji, the chairman of the Jallianwala Bagh board, led me through a narrow passageway and into the garden.

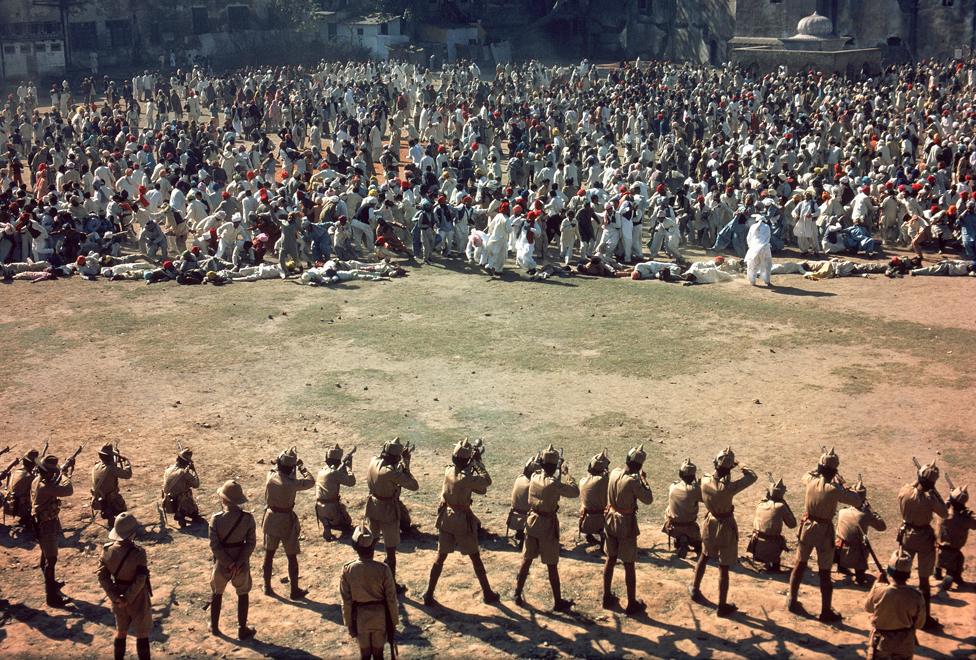

The Amritsar massacre was a turning point in Indian history

This is the route the commander of British forces, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, took with his 90 troops.

Mr Mukherji tells me how his grandfather, who was there on the day of the massacre, remembered how they formed into two semi-circles, aiming out into the crowd and blocking the only exit.

Without warning they opened fire.

Sashti Charan Mukherji ducked behind a stage that sheltered him from the hail of bullets, but he later recounted how the soldiers had aimed directly at the protesters.

They maintained the fusillade for 10 minutes, firing 1,650 rounds and killing at least 379 people (unofficial Indian sources put the numbers higher). There were 1,137 injured.

The massacre was portrayed in the 1982 film Gandhi

His grandson shows me the well where many people dived for cover. They recovered 120 bodies from there.

As we turn back to the garden, Mr Mukherji says his grandfather recalled how, their ammunition now almost exhausted, the general ordered his troops to pack up and leave.

They offered no aid to the injured.

Dyer then ordered a curfew, threatening to shoot any Indian seen out on the streets.

The wounded were left writhing in agony on the ground, says Mr Mukherji.

I'm astonished he appears to feel no animosity towards me. "You feel shame, so I feel no anger towards you," he says.

So what does this tell us about Indian attitudes to Britain?

Well, the Amritsar massacre was a key turning point in Indian history.

The historian AJP Taylor called it "the decisive moment when Indians were alienated from British rule".

As a result, the Rowlatt Act and its role in the independence movement is part of the history syllabus for all Indian children.

According to the course book used by tens of millions of Indian students, "it was the Rowlatt Satyagraha that made Gandhiji into a truly national leader."

I was worried, when I came out to India two-and-a-half years ago with my wife and children, that our family name would be a burden.

Wouldn't being a scion of an emblem of imperial evil be a handicap in my new role as the BBC's South Asia correspondent?

The answer is it hasn't been. Not at all. I've never experienced anger, even disapproval.

Former UK Prime Minister David Cameron visits Amritsar, 2013

A powerful explanation was given to me by none other than Mahatma Gandhi's great-grandson, Tushar Gandhi, when I met him outside the house in Delhi his famous ancestor used to live in.

He offered gratitude, not hostility.

"I appreciate your great-grandfather's role to provide the first nail in the coffin of the Empire," Tushar says with a laugh as we shake hands.

It's a backhanded compliment.

He explains why the law my great-grandfather wrote was so important to the Mahatma.

"The beauty of the Rowlatt Act was that he didn't have to be a spin doctor to make people understand that it was unjust," he says.

"It was so transparently malicious in intent that he could use it to create anger, to create resentment but then channel it towards the kind of protest he wanted it to be - a peaceful protest."

And, Tushar believes, it is the fact that the Indian opposition to the British was non-violent that is the key to understanding why there is not more resentment and anger between the two nations.

"It allowed us to believe we had won independence," he says.

"And it let the British console themselves by saying 'we were benevolent by giving them independence'."

But does that really explain the lack of rancour?

When I ask Mr Tharoor what he thinks, he says the answer that flatters Indians is the one reportedly given by the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, when Winston Churchill asked him why he didn't feel more bitterness about all the years of imprisonment he'd suffered at the hands of the British.

"I was taught by a great man, Mahatma Gandhi, never to fear and never to hate," Nehru is said to have replied.

"I wish that were the full explanation," says Mr Tharoor. "But I think there is a less flattering explanation, which is that forgive and forget is possible because we forget far too soon.

"I do believe we should forgive because hatred is a terrible emotion... but forgetting is unforgivable. I would say face up to the past, know it, but keep it in the past."

And, in that context, it is instructive to compare how the 70th anniversary of independence and the partition of India is being reported in India and in Britain.

In India it is not a big story.

Yes, the day will be marked by a speech from Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the magnificent Red Fort in the middle of Delhi.

There have been articles and television discussions reflecting on the state of the nation 70 years on, but nothing like the torrent of coverage the event is receiving in the UK.

In Britain newspapers and television programmes will mark the anniversary with big features and special items, while the BBC and other broadcasters have commissioned a raft of documentaries and dramas - even a film.

It isn't that India has forgotten its past - up to 50,000 people visit Jallianwala Bagh every day - it is just that the end of empire appears to be a far more compelling story in Britain than in India.

And I am not sure the British desire to "celebrate" India's independence is entirely healthy.

One senses that part of the fascination is a kind of self-flagellation.

We wallow in our shame at the horrors of our legacy in part because it reminds of what we once were - a superpower.

Enoch Powell spoke of the shared infatuation between Britain and India

It is sobering to learn what young Indians think of Britain today.

When I ask a group of 16 and 17-year-olds at Amity International School in Delhi which of the two countries is most powerful, all but one says India.

This isn't just blind nationalism, they have solid reasons for their views.

"It is our economy that is growing a much faster rate," says Sarthak Sehgal.

Doha Khan draws on history to justify her view, saying: "Before Britain came to India it gave 22% of GDP to the world and when the British left we were no more than 4%.

"So I would say that India was much more important to Britain than Britain to India, even then."

Another girl says it is a question of demographics.

"India is the second largest population, so even by numbers India is much greater.

"We are young and we have great ideas," she says to giggles from her classmates.

Across Delhi, Swapan Dasgupta echoes the teenagers' views. He is a member of the upper house of India's parliament, a senior journalist and an intimate of many senior figures in the ruling party, but he chooses a surprising figure as he seeks to explain Indian attitudes to the UK - Enoch Powell.

The former minister was infamous for warning of the "rivers of blood" that would flow on British streets if immigration from Britain's former colonies was not restricted.

According to Mr Dasgupta, Mr Powell loved India and once dreamt of becoming viceroy. He quotes a private conversation where the politician described the relationship between India and Britain as a "shared infatuation".

"There is certainly a love-hate relationship which binds the two," Mr Dasgupta reflects.

"Initially I think the hate factor was greatest. There is a lot of love, but increasingly what worries me is that there is a lot of indifference that has also crept into that relationship."

He fears the once passionate relationship is beginning to cool.

"Middle-class Indians today have a greater affinity with the United States than they have with the UK," he believes.

More Indians study there, he says, and the impact of American popular culture is greater in India now.

His analysis is damning. "Post-The Beatles and the Rolling Stones," he says, "the impact of British culture is probably limited to Downton Abbey and Upstairs Downstairs and things like that."

In part, of course, the decline in influence of Britain in India reflects the decline of British influence in the world more generally.

Like Mr Tharoor, he cites cricket as the perfect example of India's changing relationship with the UK.

Within five years of independence India had won its first Test, thrashing England by an innings and eight runs at Madras in 1952.

The Indian takeover is now virtually complete, he believes.

"Cricket is an Indian game that was accidently invented in the British Isles," he says.

"The economy of cricket is undeniably Indian now. The money is all here in India."

And what is true of cricket is true of the Indian economy more generally.

India is still a poor country in terms of per capita income, but the terms of trade with Britain have decisively changed.

With its vast market of more than 1.25 billion people and steady economic growth of about 7% a year - India is in a powerful position in trade talks.

In 2016 India had a $4.7bn trade surplus in its dealings with the UK.

Tata became a major industrial employer in the UK

The roots of the changing economic relationship run deep.

When the visionary entrepreneur Jamshedji Tata was planning the iron and steel works he believed could be the backbone of Indian industrialisation way back in the late 19th Century, he touted the idea around the finance houses of London. None wanted to invest.

"As a desperate venture," the Times reported in 1921. "The iron and steel project was offered to the Indian public and to everyone's amazement the sum needed was subscribed in a few days."

Tata's evolution has come full circle over the past century.

As the owner of Jaguar Land Rover and Corus Steel, it is now the largest industrial employer in the UK.

And, as well as Britain's most iconic car brands, it also has a firm grip on the national drink - Tata owns Tetley, the UK's largest tea business.

Mr Tharoor chuckles when the subject of trade comes up.

He argues that Indians who are angry about the wrongs committed by the British need not seek revenge.

"As the wheels of history turn, the cycles move on, you will find that history is its own revenge," he says with a smile.

"Watching Theresa May come cap-in-hand to Indian businesses looking for Indian money to revive her post-Brexit economy is to my mind the best kind of revenge you could possibly want."

Which is not to say that Mrs May is wasting her time.

Mr Dasgupta agrees that India's colonial history can still generate a sense of outrage and indignation. But Indians are, he says, practical people.

"There is a transactional attitude among Indians which is that, yes, there are uncomfortable facets of history but the question is how do we deal with it now?

"What's in it for us? As long as that extreme pragmatism rules the roost we can do business together."

Tech centres like Bangalore have grown massively

India may be a very different nation now from the one the British left 70 years ago.

It may be more interested in trade with behemoths like China and America than with the UK.

But there is a special place in Indian hearts for Britain and the British.

The abuses of empire, while not forgotten, have been - largely, anyway - forgiven.

Mr Dasgupta summarises the changes succinctly.

Cricket might now be, to all intents and purposes, an Indian game, "but there is still an iconic status to beating England at Lord's".