Why I became a jihadist poetry critic

- Published

Elisabeth Kendall in Sanaa, Yemen

Osama bin Laden shared an unlikely interest with many other jihadists - writing verse. These poems might not win any literary prizes, but Elisabeth Kendall is fascinated by them. Could they help in the fight against extremism?

Back in the late 80s, Kendall decided to study Arabic at university. An Egyptian writer, Naguib Mahfouz, had just won the Nobel Prize for Literature and Kendall was annoyed how difficult it was to find any of his books in translation. Learning Arabic was apparently the only way to find out if he was good or not.

She also thought that picking such a difficult subject might make it easier to get into Oxford (she did). It helped, too, that the choice would annoy her parents.

"I could have rebelled in lots of ways - I could have done drugs or become a prostitute or something," she says. "But I decided to study Arabic. I think that was quite painful enough for them."

Over the next 20 years, Kendall became an expert in Arabic literature - any qualms about her ability to get into Oxford were wildly misplaced. She focused on avant-garde Egyptian works, largely the angst-filled poems that appeared after the country's defeat to Israel in the 1967 Middle East War.

She tracked down authors from that time. She translated their efforts. The subject became her life.

Until one day she realised it was, essentially, useless.

"I ended up being pretty bored at conferences where everyone talks about some book no one's really heard of, goes into enormous detail about it and never works out why it actually matters," she says.

"I just thought: 'Here I am with this massive amount of training' - probably 20 years of analysing literature at that point - 'how can I make this useful?"

Her answer to that question likely annoyed her parents all over again - she decided to study the poetry of jihadism.

Today, Kendall - a senior research fellow in Arabic and Islamic Studies at Oxford University - is arguably the world's foremost expert on jihadist poetry. She can, off-hand, chat about poems written by everyone from Osama Bin Laden to Ayman al-Zawahiri, al-Qaeda's current leader (Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, leader of so-called Islamic State, does not write poetry, but did do his PhD thesis on the subject).

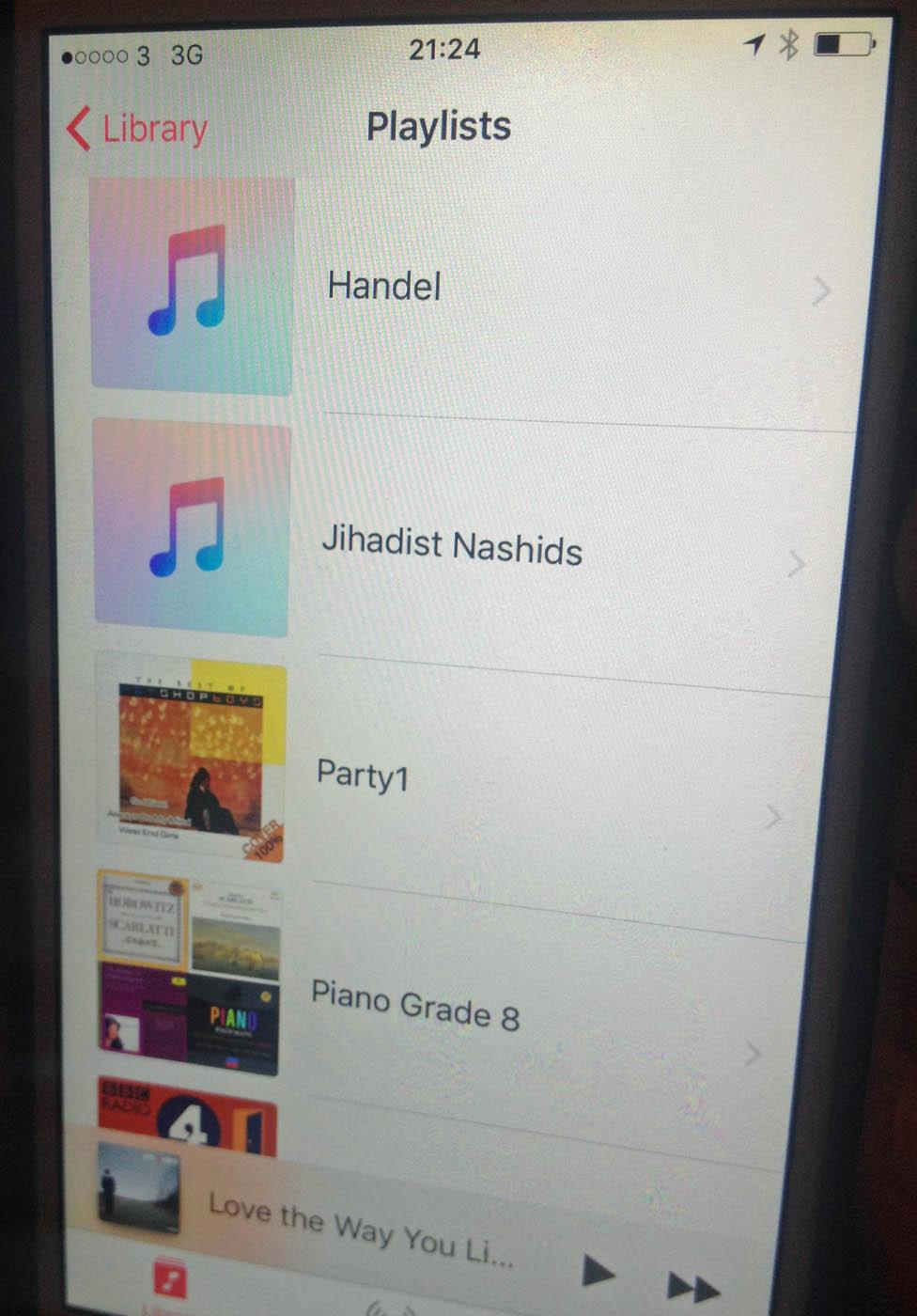

She keeps watch on multiple jihadist poetry groups through the phone app Telegram. She even has a playlist of jihadist poems on her phone, sandwiched between one of Handel compositions and another of party tunes (it features a lot of Pet Shop Boys).

Kendall's eclectic playlists

Some will find her work upsetting or controversial. But Kendall's convinced it is important, giving insight into just why jihadism flourishes, especially in the Middle East. British security services clearly agree, as they are known to have considered using poetry, among other creative methods, to combat extremism.

Kendall started looking into poems by going online and getting hold of three years' worth of magazines produced by al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, the group's arm in Yemen. The peninsula is the birthplace of Arabic literature, so the choice seemed appropriate. She quickly discovered that poems featured on almost a fifth of pages.

"It was astonishing," she says. "I knew it was important as soon as I saw how much there was. Why would they be wasting their time on it otherwise? Plus, anybody who's spent time in the Middle East knows how important poetry is. Any tin-pot taxi driver in Cairo can recite poetry."

The poems Kendall found weren't simply propaganda. Yes, there were a lot calling for attacks and ones urging people to join the group ("Where are you as Muhammad's community burns in flames?"), but there were others lamenting dead friends ("I know you're with Allah… but, if I'm honest with myself, I am going to miss you") and even ones trying to instil conservative values in women ("How much she pleased me when she walked about not letting her veil fall," goes one of those, clearly from a male point of view).

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula van, offering jihadist CDs and books

What struck her most about them, though, was not that variety, but how much they repurposed old poems from hundreds of years ago.

"It's actually one of the very, very few occasions where I thought that my undergraduate degree in Islamic studies had some use, because having spent so much time looking at classical poetry, I was able to read one of these and go, 'That sounds vaguely familiar,' then trace it back." She discovered that over half were plagiarised from the classical tradition. Nearly 10% turned out, ironically, to be from the pre-Islamic era.

Even the new poems were written so they looked as if they had been dreamt up during the time of the Prophet Muhammad, rather than by a bored jihadist driving through a desert a few weeks before. It was as if al-Qaeda wanted anyone hearing them to think they could have been written by a distant ancestor, someone just like them.

"If I'm sitting here as a literary judge on the Booker Prize or something, I'd say most of this stuff's utter rubbish," Kendall says. "But it's not designed to be good literature - it's designed to plug into a tribal tradition that's authentic and speaks to people's hearts, and it does that."

Kendall could have just stayed in her office glued into jihadist social networks to research these poems, but she didn't. Not long into her research, she went to Sanaa, Yemen's now tragically war-torn capital, to see what material was there.

Kendall in the Yemeni desert

"I started hunting around bookshops, and you wouldn't get the stuff easily," she says. "It was difficult to know what terminology to use. 'Poetry about jihad?' That didn't work. It turned out to be 'Enthusiastic poetry', 'Poetry for a cause'. I'd say that and, 'Ah!', a backdoor would open and there you go."

She also surveyed Yemeni tribespeople on poetry (among many other topics), to check it was important to their daily lives - some 84% of men and 69% of women said it was - and while travelling around sometimes played her minders jihadist songs from her phone just to gauge their reactions.

"Once, one turned around and went: 'Doctor, this is rubbish! If you want good jihadi poetry, we'll find you good jihadi poetry.'"

Kendall gives regular talks on the subject and if you hear one you could be startled. At an event in London earlier this year, she happily read excerpts from one of her "favourites", and later said, of two al-Qaeda poets, that "these guys were so talented, even I felt a pang of regret when they got droned."

Kendall with tribesmen in Yemen

But her audiences never look shocked, because it's always clear her sympathy lies entirely with the Yemenis exploited by such groups. Yemen has sadly long been a country with so few opportunities that jihadism could seem to some people like their only option.

"I get a sense of desperation [sometimes in these poems]," Kendall says. "'What can we do? We have corrupt leaders who've pocketed all the aid money, who don't invest in us, and they're the ones supported by the West. We just need to take over, implement Sharia, ban everything and we'll be ok.'

"I mean, it's desperate stuff."

Kendall's sympathy for the Yemenis has found her working beyond academia. She's involved in educational projects in the country and has helped establish a newspaper to give locals a voice (with a poetry page, naturally). She even represents tribes from the Mahra province, in the east, flying around the world to get their views heard at the UN and elsewhere. She speaks at their inter-tribal meetings, an honorary man for the occasion.

Kendall speaking about her research in Riyadh

Jihadists know who she is due to all this. Earlier this year, while passing time in Dulles airport, in Washington DC, she logged onto some jihadist communications and found herself mentioned. She also believes some members of al-Qaeda once came to check her out in Yemen, when she was working with the tribes. "They knew who I was. They knew what I'd published. They knew how to argue," she says, still clearly unnerved by the occasion.

Did they have guns? I ask. "Yes, but everyone has guns," she says, her laughter breaking the tension.

Could poetry help turn such people away from jihad? "I think it could," she says. "I'm not suggesting counter-terrorism experts start writing poetry. That'd be a huge mistake and counter-productive, because it wouldn't be authentic."

But countries could help fund publications that do promote anti-jihadist poetry written by locals. Kendall insists you can find such poems if you look closely and give people the opportunity to speak. Pseudonyms would be essential, unfortunately.

Jihadist poetry has clearly taken over Kendall's life in a similar way that avant-garde Egyptian literature once did. "I do live and breathe this stuff," she says. She has even got to the point where she makes jokes about it, although she says that's normal for anyone working with jihadism.

"You have to have a sense of humour when doing this, otherwise how would you continue?" But this time, her obsession seems to only partly be because she finds the subject fascinating. It's clear another driver is she simply thinks it is important.

"Lots of people spend all their time looking at what a group like Islamic State pumps out in English. And you could do that and feel like you're getting somewhere [in understanding them], and maybe you would be with a small group of foreign fighters. But that completely neglects the vast majority of these groups.

"We always ask the question, 'What radicalises people?' and not the bigger question, 'What enables these groups to be tolerated among well-armed populations?' And the way they do that is just getting into the rhythm of the local culture with things like poems.

"If they didn't do that, they wouldn't survive. And if they didn't have a safe haven, foreign fighters would have nowhere to go."

Photographs courtesy of Elisabeth Kendall

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.