Will my anorexia stop me going to university?

- Published

For the past two years Maya has been in the grip of anorexia. Despite her illness, she wants to move on with her life, so this year she decided to sit her A-levels and try to enter university. The BBC's Sarah Bowen followed her efforts in the months leading up to results day.

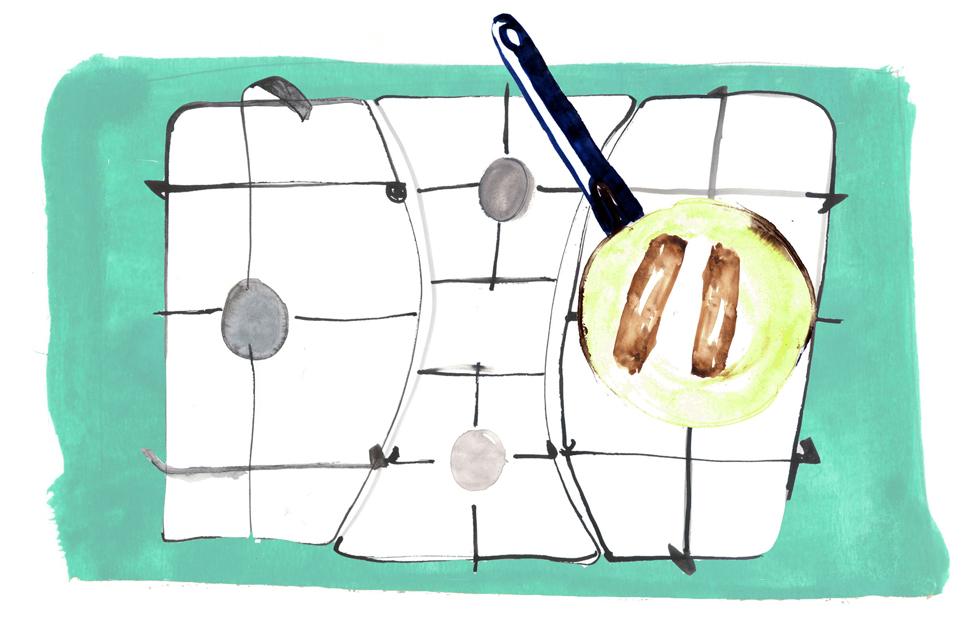

Maya walks down to the kitchen, where her mother is frantically trying to get dinner ready. If her food is not ready at the time she expects, Maya may refuse to eat it.

It's too late to heat up the oven, so she's dry-frying two vegetarian sausages in a hot pan, without oil.

When Maya sees this she freezes. "Why are you frying them?" she asks, panic in her voice. "You're meant to do them in the oven!" A huge argument follows. Maya storms back upstairs. Dinner is ruined.

This is what life has been like at home ever since Maya developed anorexia.

"I hate my illness so much," she says. "It's more than just starving yourself of food, it's starving yourself of everything - I starve myself of friends, I starve myself of family, I starve myself of education."

She has missed almost a year of school but now she has decided she wants to sit her A-levels and go to university.

It is something Maya desperately wants, so the pressure is on. "These exams are the key to proving to myself that I have a life beyond this illness, that I can beat it," says Maya. "In my moments of doubt I just get so scared, because if I fail the exams how am I going to get better, how am I going to succeed in life?"

Studying is a challenge. It's hard to concentrate when she is hungry, and after eating she feels compelled to exercise. "The thought of sitting down and not constantly moving is too stressful," she says. "Every single thing in your life is about using as much energy as you can, to compensate for the food that you're eating."

Maya's anorexia diary

Her mother feels the exams will give Maya a focus which may help her recovery. "There is enormous pressure around these A-levels, but it's been her motivation," she says. "If I was to take that away from her, I think she'd be completely lost."

Maya knows she has to nourish her brain in order to revise, but the thought of putting on weight terrifies her. "It is a phobia where you are afraid all the time of the consequences of recovery," she explains. "I constantly feel like every single thing I eat is a weakness, a failure."

Her obsession with food began when she was revising for her GCSEs in 2015. She told her mother that she wanted to eat by 7pm every night and have no chocolate, ice creams or meat - just "power foods" like vegetables and fish.

"It started off being about nutrition," Maya says. "I told myself I was eating healthily." But it soon became about calories. And then she started exercising more to burn off any calories she ate.

"I used to do secret exercise in my room. Or we would have an argument, and I would run out of the house and sprint," says Maya.

By the time she started at a new, very competitive sixth form, all she ate was steamed vegetables.

Maya began losing weight, but nobody realised quite how much. Her mum thought she was growing taller.

When Maya's periods stopped, she didn't tell anyone.

It wasn't until that November, when an old friend pointed out how unwell she looked, that the family realised something was wrong. Their GP referred Maya to hospital. They waited anxiously until the appointment finally came in January.

"Wow, that was a stressful day," says Maya. "We didn't realise how serious it was until my assessment."

Maya was severely underweight. Her blood pressure didn't even register - the doctor thought the equipment was faulty, but it was because she hardly had a pulse.

They were just in time - the doctors said she was lucky to be alive.

Her hair was falling out and she was furry, her entire body covered in a soft down.

"I was so shocked, I just wanted to get her home safely," says her mother.

She agreed to nurse Maya at home, according to strict guidelines.

Since then, they have been locked in a battle of wills. The only way for Maya to get better is to eat and gain weight, but she doesn't want to, because of the anorexia.

"It's like a prison sentence," says her mother. "It's completely exhausting because I spend all my time making sure that she's got the correct food."

Maya is meant to eat six small meals a day. If her food is not exactly how she expects it, she panics and her mood flips. Some foods, like cucumber, apples or bread, she's happy to eat - but others, like cream, chocolate muffins or rice, scare her.

Find out more

Listen to: In the grip of anorexia via iPlayer

Maya and her mother told their story to Sarah Bowen on BBC Radio 4's The Untold

Maya and her mother spend hours in the kitchen, arguing over one meal.

"We have written out meal plans but you try battling with somebody who is so clever - it's hard," says her mum.

"The anorexia is very manipulative and devious. When I do stand up to her she screams, and plenty of times she has run out of the house. She self-harms and uses it as a threat, and that is the hardest thing."

The rows at mealtimes are terrible and affect the whole family. Her father is so worried about the effect on Maya's brother that he's considering moving out with him and setting up a second home.

"The illness is so selfish that in the moments I am so distressed, I don't think about my family. My brother has become depressed and upset," says Maya. "It is a difficult illness and does turn you into a monster."

Maya's feelings after a family argument (from The Untold)

After two years without progress, her mother feels stuck. "I feel very useless and a bit demoralised. Every time I see a little glimmer of hope, it all closes in and it's dark clouds, thunder, bad times," she says.

When Maya was first diagnosed she went into hospital every day to have meals and therapy. This was effective, even though she found it upsetting.

"I struggled to see other young people so ill. I felt a sick kind of competition where if someone was thinner than me, I would compare myself, and I hated being fatter than that girl. I hated it while I was there, but in hindsight it was good because it acts as a motivation to get better."

By April 2016 Maya seemed better and her mother went back to work. But things soon took a turn for the worse, and she quit completely to look after Maya full-time.

Before her illness, Maya was fun to be around. She had lots of friends and she was independent, capable - with a perfectionist streak when it came to her school work.

But her mother has learned that it's not helpful to look back. "Young people with anorexia have to look at a whole new identity. They've got to reconstruct themselves. It's really hard for them to consider their body shape, their face, how their arms and legs will look - all these things that we take for granted."

This is now Maya's second go at recovery. She feels it's going well.

"Compared to last time round, my mindset is different and I want to do it. But my parents think I am doing badly because I'm not putting on weight."

She thinks it's unfair that she's always being judged on her weight. "I don't think being at a low weight is a problem but everyone around me does, they think I'm dangerously ill."

But her mother can only go on evidence. "I'm not sure whether she's still throwing away all those sandwiches that I've made her every single day for school," she says.

At the same time, she can see that Maya is working hard - the promise of university and independence are keeping her motivated. "She can see that there's life out there, it's within her grasp," she says.

But she has made it clear that, no matter what grades she gets, if Maya is not well enough she can't go to university.

"I think she could [recover], she is wilful, she has got discipline, but it's whether she can sustain it," says her mother. "What anorexia does, it creeps in through the cracks - if she is upset over a boy or teacher, it will find a crack."

The atmosphere at home improves when the family decides to have separate meals, but Maya still won't eat unless she's being watched over by her parents. She doesn't have a single unsupervised meal. "I put the responsibility on them because they are the ones who get more worried if I lose weight," she says. "I don't want to eat every meal."

She wants to be praised for every mouthful, but her parents find it increasingly difficult to do so. This leads to more rows.

The exams go by in a blur. After the last one, Maya's friends all go out for the evening without her. She feels sad and left out.

"My illness has transformed me into someone no-one wants to be around," she says.

"The illness kidnaps you. It wants you to be with it, not your friends."

The summer holidays begin, and the long wait for results.

As her mother feared, Maya struggles without the structure of a school timetable, homework, and exams to prepare for, and her mental health gets worse over the summer months.

She doesn't meet up with her friends, and instead watches their adventures unfold on social media.

On holiday in France, Maya is expected to eat along with everyone else. Suddenly she's faced with salads dressed with oil and vinegar and creamy potato Dauphinoise. She forces herself to eat. "Don't focus on the food, enjoy the rest of the day," she tells herself.

Back home, her pride at having tried these new foods turns to dismay - she has actually lost weight. "I thought I was doing really well - but I overestimated how much I ate," she says.

Something very important happens over the summer: Maya turns 18, and the hospital now treats her as an adult.

It's a big shift. Parents are no longer of such significance and her mother worries that Maya won't get such a high level of support.

But Maya is excited about adult therapy. Her first task is to write two letters to a friend, five years from now - one where she imagines she has recovered from anorexia and one where she hasn't.

"That was really powerful because I realised that if things don't start getting better now, they're only going to get worse," she says.

17 August 2017: A-level results day. Maya is very nervous. There are tears in the car outside school, but when she brings herself to open the envelope everyone is astonished.

She has three A* grades, and has secured a place at her university of choice. "She is incredible," says her mother. "I don't know how somebody who is so ill can perform so amazingly."

"When my therapist heard my results she said: 'Well done - but this is not going to help your perfectionism,'" says Maya, laughing.

But as well as the good news, there is also bad news. Unfortunately, when it comes to her weight, she has not made the required progress.

By the time of her exams in June, she had gained some weight. "I distracted myself from my urges by studying," she says. But over the summer she lost it all again.

The decision is taken to delay her university entry for a year, to focus on getting better.

Her mother is worried about what the year will bring. "She's very lost. It's a bit like a blank canvas - and a blank canvas is scary. Everything is out there, but where do you start?"

Help and advice:

In September, Maya's friends start leaving for university. It's a difficult moment for her.

"I did initially have a few days where I felt really low and left out and didn't know what to do," she says. "I didn't have a job, I wasn't going travelling… I just felt so bad."

But then things start looking up. Quite a few of her friends are having a year out, and Maya starts seeing them again.

Then she applies for two jobs - and is offered one.

Despite her parents' concern that doing nothing will be harmful for Maya, they are not sure a full-time job is a good idea.

"My mum thinks I should have more time at home, relaxing and resting," says Maya.

"But if I have nothing to do that gives me a sense of achievement, I'll just go and run up and down the stairs until I'm tired.

"The exercise is my least favourite part of the disorder because it feels like a waste of time."

And Maya is now putting on weight again. She is trying hard to accept this new turn of events, because she really wants to get better.

"I do want a boyfriend," she says. "I want to look and feel like a typical 18-year-old."

There is so much that lies ahead of Maya - relationships, university, employment - if only she can beat her illness.

Maya's name has been changed.

Illustrations by Katie Horwich

Additional interviews and production by Vibeke Venema

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.