My work as a prostitute led me to oppose decriminalisation

- Published

For most of her life in prostitution in New Zealand, Sabrinna Valisce campaigned for decriminalisation of the sex trade. But when it actually happened she changed her mind and now argues that men who use prostitutes should be prosecuted. Julie Bindel tells her story.

When Sabrinna Valisce was 12 years old her father killed himself. It changed her life completely. Within two years, her mother had remarried and the family had moved from Australia to Wellington, New Zealand, where her life was miserable.

"I was very unhappy," says Valisce. "My stepfather was violent, and there was no-one to talk to."

She dreamed of becoming a professional dancer and set up a lunchtime ballet class at her school, which proved so popular that a well-known dance group, Limbs, came to run lessons.

But within months she found herself on the streets, selling sex to survive.

Walking through the park on her way home from school, a man offered her $100 for sex.

"I was in school uniform so there was no mistaking my age," she says.

Valisce used the money to run away to Auckland, where she checked into the YMCA.

"I tried ringing someone to ask for help in the phone booth which was outside the hostel, but it was engaged, so I waited," she says.

"The police stopped and asked what I was doing. I said, 'Waiting to use the phone'."

The officers pointed out that no-one was using the phone, so there was no need to wait. They thought they were being "terribly clever" Valisce says - but didn't seem to understand when she explained that it was the telephone she was calling that was engaged.

"They searched me for condoms thinking I was a prostitute because the YMCA was behind Karangahape Road, the infamous prostitution area.

"Ironically, that was what gave me the idea to go get some money. The police scared me but I knew I was going to be on the streets if I didn't get cash, and the act of leaning against a wall was all it took to be searched and threatened anyway, so I figured it made no difference if I was or wasn't."

Karangahape Road pictured in 2003, shortly after the law legalising prostitution was passed

Valisce walked over to Karangahape Road and asked one of the women working there for advice.

She pointed out two alleyways where Valisce could work. "She also gave me a condom, told me basic charges and advised me to make them fight for services I was prepared to do, to avoid fighting against services I wasn't prepared to do. She was very nice. Samoan, too young to be there, and clearly been there for too long already."

In 1989, after two years working on the streets, Valisce visited the New Zealand Prostitutes Collective (NZPC) in Christchurch.

"I was looking for some support, perhaps to exit prostitution, but all I was offered was condoms," she says.

She was also invited to the collective's regular wine and cheese social on Friday nights.

"They started talking about how stigma against 'sex workers' was the worst thing about it, and that prostitution is just a job like any other," Valisce remembers.

It somehow made what she was doing seem more palatable.

She became the collective's massage parlour co-ordinator and an enthusiastic supporter of its campaign for the full decriminalisation of all aspects of the sex trade, including pimps.

"It felt like there was a revolution coming. I was so excited about how decriminalisation would make things better for the women," she says.

Decriminalisation arrived in 2003, and Valisce attended the celebration party held by the prostitutes' collective.

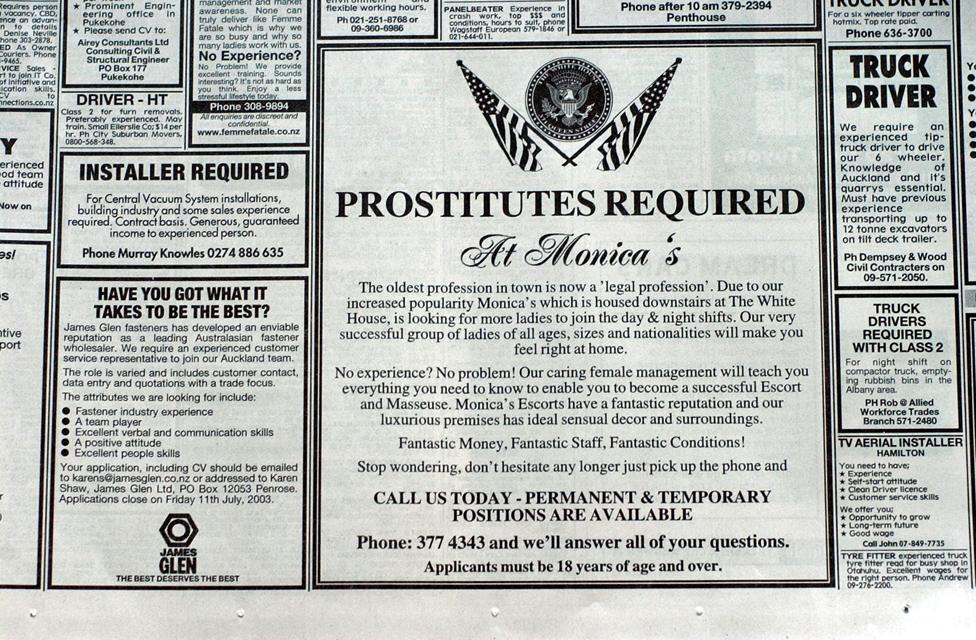

When prostitution was legalised in 2003, job adverts appeared in the New Zealand press

But she soon became disillusioned.

The Prostitution Reform Act allowed brothels to operate as legitimate businesses, a model often hailed as the safest option for women in the sex trade.

In the UK, the Home Affairs Select Committee has been considering a number of different approaches towards the sex trade, including full decriminalisation. But Valisce says that in New Zealand it was a disaster, and only benefited the pimps and punters.

"I thought it would give more power and rights to the women," she says. "But I soon realised the opposite was true."

One problem was that it allowed brothel owners to offer punters an "all-inclusive" deal, whereby they would pay a set amount to do anything they wanted with a woman.

"One thing we were promised would not happen was the 'all-inclusive'," says Valisce. "Because that would mean the women wouldn't be able to set the price or determine which sexual services they offered or refused - which was the mainstay of decriminalisation and its supposed benefits."

Aged 40, Valisce approached a brothel in Wellington for a job, and was shocked by what she saw.

"During my first shift, I saw a girl come back from an escort job who was having a panic attack, shaking and crying, and unable to speak. The receptionist was yelling at her, telling her to get back to work. I grabbed my belongings and left," she says.

Shortly afterwards, she told the prostitutes' collective in Wellington what she had witnessed. "What are we doing about this?" she asked. "Are we working on any services to help get out?"

She was "absolutely ignored", she says, and finally left the prostitutes' collective.

Until then, the organisation had been her only source of support, a place to go where no-one judged her for working in the sex trade.

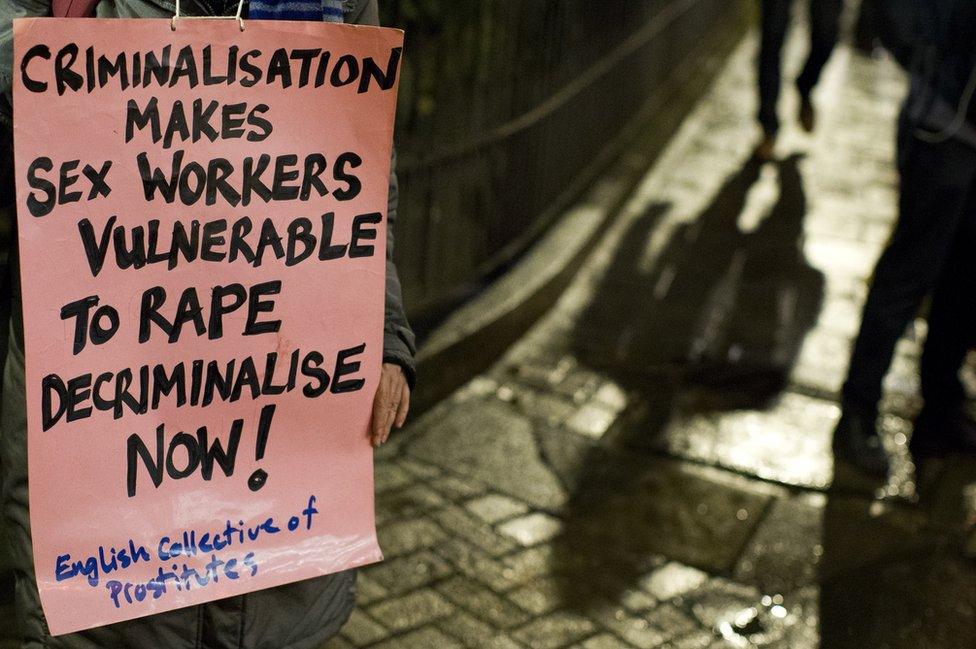

The English Collective of Prostitutes also campaigns for decriminalisation

It was while volunteering there, though, that she had begun her journey towards becoming an "abolitionist".

"One of my jobs at NZPC was to find all of the media clippings. There was one thing I read: it was somebody talking about being in tears and not knowing why, and it wasn't until they were out [of the sex trade] that they understood what those feelings were.

"I had been through that for years [thinking], 'I don't know what's going on, why am I feeling like this?' and realised when I read that: 'Oh God, that's me.'"

For Valisce, there was no turning back.

She left prostitution in early 2011 and moved to the Gold Coast in Queensland, Australia, seeking a new direction in life, but was confused and depressed. When her neighbour tried to recruit her into webcam prostitution, she politely declined. "I felt like I had 'whore' stamped on my forehead. How did she know to ask me? I now know being female was the only reason", says Valisce. Afterwards the neighbour hurled insults at Valisce whenever she saw her.

Valisce began to meet women online, feminists who were against decriminalisation and described themselves as abolitionists - the abolitionist model, also currently being considered by the UK's Home Affairs Select Committee, criminalises the pimps and punters while decriminalising the prostituted person.

Valisce set up a group called Australian Radical Feminists and was soon invited to a conference. Held at the University of Melbourne last year, it was the first abolitionist event ever to be held in Australia, where many states have legalised the brothel trade.

Melbourne itself has had legal brothels since the mid-1980s, and although there is a lot of vocal support for the system, there is also a growing movement against it.

One Melbourne bordello floated on the stock exchange in 2002

She describes this period, when she became a feminist activist against the sex trade and began to feel free of her past, as "the start of my new life".

"I exited first emotionally, then physically and lastly intellectually," she says.

After the conference Valisce went to a doctor and was diagnosed with PTSD.

"It was as a result of my time in prostitution - it had affected me badly, but I was good at covering up the effects," she says.

"It takes a long while to feel whole again."

For Valisce, the best therapy is working with women who understand what it's like to go through the sex trade, and those who also campaign to expose the harm prostitution brings.

She is also determined to ensure that the women who are usually silenced by their abusers have a voice.

"It's not my goal to trap people in the industry or tell anyone to go get out," she says. "But I do want to make a difference, and that means speaking out as much as I can, in order to help other women."

Julie Bindel is the author of The pimping of prostitution: Abolishing the Sex Work Myth

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.