Baby loss: 'People sharing stories is the biggest comfort'

- Published

Stillbirth is rarely spoken about. But insights from those who have navigated the heartbreaking experience can help parents come to terms with their grief.

A new website, Stillbirth Stories, which collects detailed interviews with mothers, fathers and clinicians, has been launched to coincide with Baby Loss Awareness Week.

It aims to nurture a conversation about a once-taboo subject. Here are extracts of some of those stories.

"There was a cold cot that I could put Jannah in. She could stay overnight. And that was really lovely - it was special."

At 41 weeks, Rabia went into labour. But in hospital, she and David were told there was no heartbeat. Jannah was stillborn. The couple were able to stay with their baby for two days in the hospital's bereavement suite.

David recalls the time they spent together as a family:

"I was with her for two days in the hospital - they were absolutely amazing, what they did. They had their own bereavement suite, so you [could have] your own time with the baby.

I never let Jannah be on her own at any moment. I wanted someone always with her - even though I knew she had gone. But I always felt that she had the right to be loved for those days - to be hugged and kissed and whatever, and not left alone. Like a baby.

"The bereavement suite had a double bed, so I could stay as well. It was like us three sleeping together. It was quite nice to have her with us as part of our family. We spent a lot of quality time with her [there]. We talked to her, made lots of videos, lots of photography, and tried to keep as much memory of her as [we] could. I don't know if it's odd or not, but I looked at every little part of her, right down to between her toes.

"I've got somewhere I can go, and I know she's there. I can put flowers on her grave - but it's not the same."

Alexis was stillborn at term. It was 1963 and neither Marjorie nor her husband, Alex, were allowed to see, or hold, their baby. It would be another 50 years before they found out where she had been buried.

"I knew Alex had to go and register the baby. I must have said to him: 'What are they going to do with her?' And he just said: 'Well, you know, they're going to have her buried.' We went to the hospital at one point and asked where she was, and they just said that she had been buried somewhere in Stockport, in one of the cemeteries.

"I'd started to have more children, and it was, you know, one day we will find her. Until the day came that we did go and look for her.

"We went to the big crematorium in Stockport, and they sent us to the central library. They said everything was on microfilm, and we looked through it and we found two burials around the time Alexis would have been taken there. She was born on the 15th [of April], there was just this one buried on the 17th - a girl of 31. And underneath it said: "Stillborn". So I knew they'd put a stillborn in the grave. And that's when we went back to the cemetery. I saw a different lady, and she said: 'Oh did they not get the little book out for you? We have a little book for all the stillborn babies.' She brought it, and it was there, and she gave us a grave number."

Find out more

Stillbirth Stories, external is a collection of honest interviews from parents and and those who have worked with them. Besides offering emotional support, the site is a learning resource for clinicians. The project is supported by Wellcome, external.

"We went to look for it, and couldn't find it. There was no stone, it was just grass. Eventually, I did ask if I could put something on [the grave]. They said: 'No. The grave belongs to somebody, it's registered to somebody. You can put flowers on, but no, you can't put anything else on.' So, for a while, I just bought something that you could stick in the grass and put flowers on. Then I got a bit angry about it. I've had a proper stone flowerpot with her name put on it.

"Over the other side [of the cemetery] is where all the babies are buried. And that haunts me - to think that she was just put in a grave with somebody that I don't know. I just hope and pray it never happens to anybody else, because it's one of the cruellest things you can do to a couple. I know I can go there and put flowers on for her, but it's not the same."

"I bathed him for the funeral, which you do in Muslim culture."

Mohammed was stillborn at 27 weeks gestation. Parents Shazia and Omar decided to bury their baby according to the Muslim faith. Shazia says the hospital midwife appreciated the need to have the body released for the funeral as quickly as possible, and helped with the process.

It was Omar who performed the Ghusl - or ritual bath - for the funeral.

"So it was just me and him, and a priest. That was the time, I guess, it was just us two.

"That was the toughest part of all of this for me. That's where, you know, you're sort of past the birth and it's the day of the burial, and the funeral. It's a duty that you need to do. At that time, I guess, religion sort of took on a different aspect for me.

"And it was this grief that actually cemented my religion a little bit: maturing and going through that experience, learning what you do when, when it's your responsibility for the funeral. That point where I was bathing him, was the point where I was close to totally breaking down. But I soldiered through - for want of a better phrase.

"Something that I'm proud of, is that me and Shazia made it through it, having seen some really, really low, low times, to where we are now."

At the time of interview Shazia and Omar had recently had their fourth child.

"I just want people to understand it's much more common than they think. There's like over 300 babies a month stillborn."

Guy was stillborn on 13 November 2015 at 25 weeks and five days, to parents Sam and Martin.

"We had a couple of close friends we'd told at the time [when Guy died]. I just physically couldn't even speak to get the words out to tell people.

"Once he was born, we just decided to use Facebook. We thought that is the quickest way to get the message out there and not have to speak to anybody really.

"I got such an overwhelming response from that. So many people messaged me privately to say that they'd had similar experiences; that they'd had losses, various stages, and that was - I want to say comforting, to know that there were other people out there. But I wondered why nobody had ever said anything. And even then, they were posting it privately to me and I thought, well, tell people.

"It was nice to know that they'd opened up and they'd gone on to have their own children, and were trying to put that little bit of hope out to us.

"People sharing their stories is the biggest help, the biggest comfort - because a lot of people will shy away from it.

"The thing about meeting people online, is that you don't know if they're who they say they are. But these were all genuine people sharing their stories. I ended up meeting a few [of them] at a memorial service. A couple of the girls that I was following were going, so we said we'd meet up there, just to put faces to the names, and the stories. Over the last few months, I've just found my own little group of friends

"I've put [Guy's] story out there quite a lot. I've done a lot of fundraising, mostly for Tommy's. Then we've done some for Aching Arms, because they're the charities we feel have helped us the most."

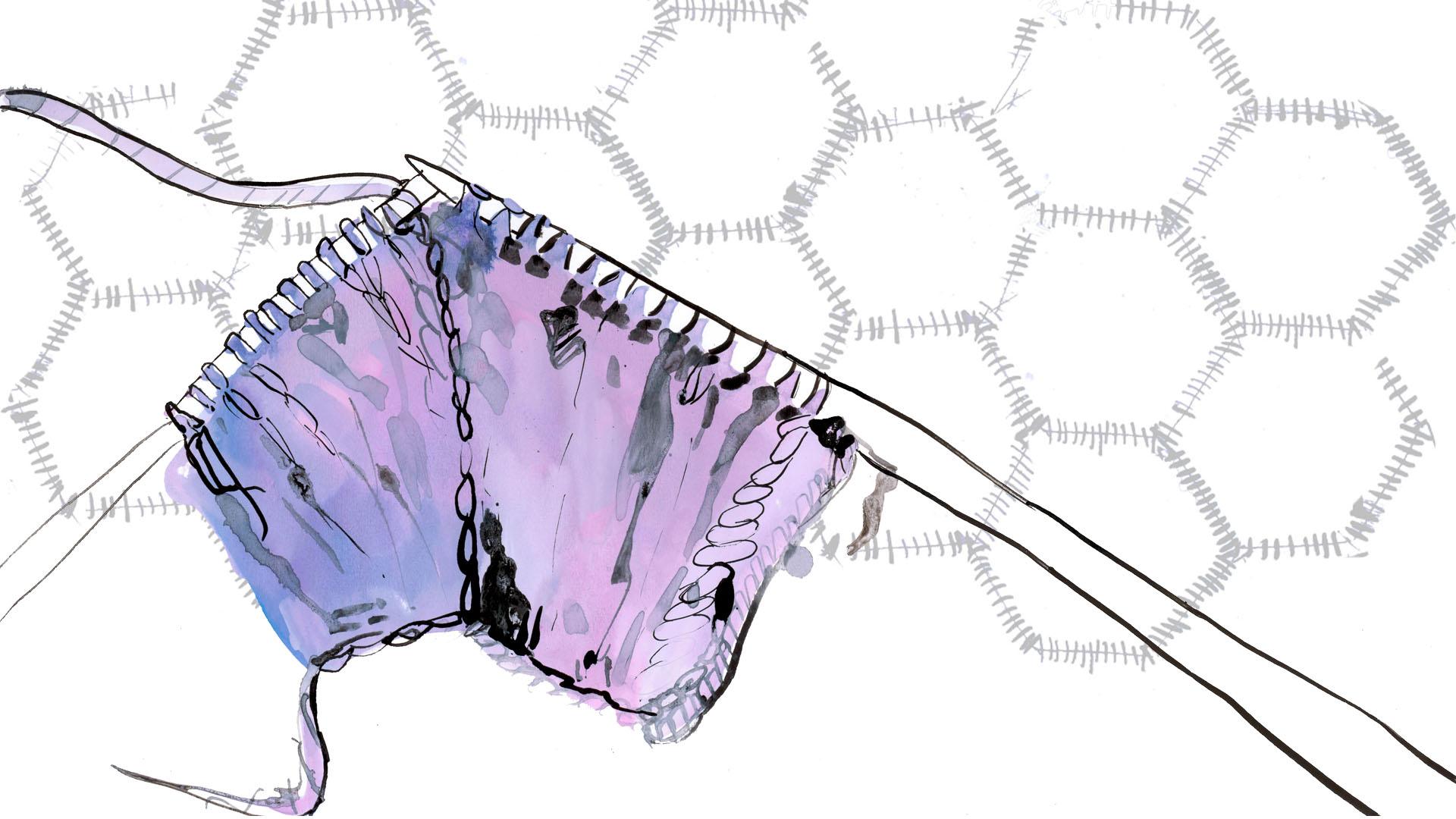

"We had like a little selection of little knitted dresses, little gowns that a woman had made via a charity"

Petal was born at 23 weeks and 6 days of pregnancy to Aimee and Marc. In the UK, the definition of 'stillborn' is a baby born with no signs of life at 24 or more weeks of gestation. Had Petal been born one day later she would have been legally 'stillborn'.

"Before I was induced, the bereavement midwife come round and she gave us a selection of clothes that Petal could have to wear. She was too small for babygros and things. We'd bought blankets and dolls and things for her [the day before], but none of the clothes would fit her. We had a selection of little knitted dresses, little gowns that a woman had made via a charity. It was really personal to be able to pick something for Petal to wear. So, when I delivered her, Marc bathed her and then dressed her in a little purple, pink gown, with a little hat and gloves.

"It was precious. It's all we have of her. That's the memory that I have of her that feels real - that she was really here.

"She was classed as a late miscarriage instead of a stillbirth. If she would have been born 22 hours later, I would have been able to register her and she would have had her own death certificate. We don't have any legal documentation for her.

"Sometimes I feel like that because she doesn't have a death certificate, she never existed.

"Since I lost Petal, I felt that people pitied me because of that experience, but I don't want to be defined as the mother who lost a child. I'm also a mother of three healthy children as well, who just wants to say that there is help out there for bereaved parents to carry on."

Where to find help

Tommys, external - Saving baby's lives

Sands, external - Stillbirth and neonatal death charity

Illustrations by Katie Horwich

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.