How do you decide when a statue must fall?

- Published

A defaced statue of Cecil Rhodes is removed from the University of Cape Town in 2015

We name buildings after people, or put up statues to them, because we respect them. But what if we then discover they did wrong? In what cases should the building be renamed, or the statue be removed, asks the BBC's in-house philosopher, David Edmonds.

It's been described as "the loveliest room in Europe". Gothic on the outside, classical on the inside, it's a cathedral but not for the gods. It's a cathedral for the worship of books. The Codrington Library in All Soul's College is one of Oxford University's hidden architectural gems. It's also got a back story, and one rather embarrassing for the College.

Inside the library is a magnificent marble statue of the former All Souls Fellow after whom it is named, Christopher Codrington. Codrington died in 1710. His will was found, so we're told, in his boots.

A fortune - £10,000 - was bequeathed to All Souls for the books and the building.

And the source of all this money? Well, Codrington was descended from a line of sugar magnates. Their plantations were in Barbados and Antigua - and they were worked by slaves.

All around the world, institutions are dealing with a conundrum. What to do about statues or buildings or scholarships or awards, honouring or funded by people we now regard as seriously morally flawed? It's causing tensions from Princeton, external to Cape Town, external to Sydney, external.

You don't have to walk far from All Souls College to find another illustration of the dilemma - it takes just one minute, in fact.

Oriel College has become one focus of the Rhodes Must Fall movement. Some students have objected to the statue of Cecil Rhodes - it's inappropriate, they say, to have a statue of this 19th Century businessman, an advocate of white supremacy whose life was so deeply enmeshed with British imperialism.

Despite a vociferous campaign to have the statue removed, the College announced early in 2016 that Rhodes will not fall (a decision no doubt influenced by threats from potential donors that if it were pulled down or relocated, they would withdraw their bequests).

According to Daniel Butt, a politics fellow at Balliol College, arguments about whether to pull down or move once revered figures - like Rhodes - inevitably provoke powerful emotions.

"We want to have positive views of our ancestors, we want to think we come from a moral community, that people who came before us were good people - and also that we're good people," he says. "We react very strongly to the idea that just by living somewhere or having a certain identity we're linked to historical injustice or present-day wrongdoing."

Oxford attracts millions of tourists a year. Few of them will be aware that everywhere you look in the city you can find links with Britain's colonial past.

Balliol College, where Daniel Butt teaches, is no exception. In the late 19th Century it educated many of those who went on to administer the Empire, including three successive viceroys of India (Lansdowne, Elgin and Curzon).

How then should we deal with discomforting reminders of the past? One approach is to do nothing. The do-nothing advocates say history shouldn't be rewritten. To do so would be a form of censorship. And, they say, it's ridiculous to expect every great historical figure to be blemish-free, to have lived a life of unadulterated purity.

Even those held up as saintly figures, such as Mahatma Gandhi or Nelson Mandela, had flaws (Gandhi's attitude to women is excruciating, seen through 21st Century eyes).

So we're on a slippery slope. If we were to denude Britain of all the statues of dead politicians and soldiers who held a few views we now find problematic, the country would be littered with unoccupied plinths. And what message would it send to contemporary philanthropists? Give generously today, and risk having your reputation trashed tomorrow.

But this "do-nothing" position seems too extreme. Imagine that Goebbels had endowed scholarships to Oxford, like Rhodes. Would anybody seriously claim the Goebbels Scholarships shouldn't be renamed (would anybody want to be a Goebbels Scholar?) or that a Goebbels statue shouldn't be demolished?

How do you decide when a statue must fall - join BBC Radio 4's Global Philosophy Club debate, external

Daniel Butt says some sorts of crime or reprehensible behaviour are rightly regarded as so severe that they can't help but contaminate our overall assessment of that person's moral worth.

"There are some forms of moral wrongdoing that are beyond the pale, that are just so wrong that it becomes completely inappropriate to have that kind of person as a role model, to put them on a pedestal and look up to them," he says. "Paedophilia might be an activity which falls into this category."

Still, the vast majority of people are neither complete monsters nor complete angels. So what is needed is a middle path, a way of thinking about which buildings to rename, which statues to leave, which to remove. Dr Butt believes it would be a mistake to seek a universal formula. "There are so many different variables. So we don't want a one-size fits all. We have to examine particular cases on their merits."

What sort of considerations, then, should come into play? One may be whether the views or actions of the figure in question were typical for their time. If so, that could make them less blameworthy. Another is the extent of their misdeeds and how that is evaluated against their achievements. Churchill held opinions that would disbar him, external from political office today - despicable yes, but surely massively outweighed by the scale of his accomplishments.

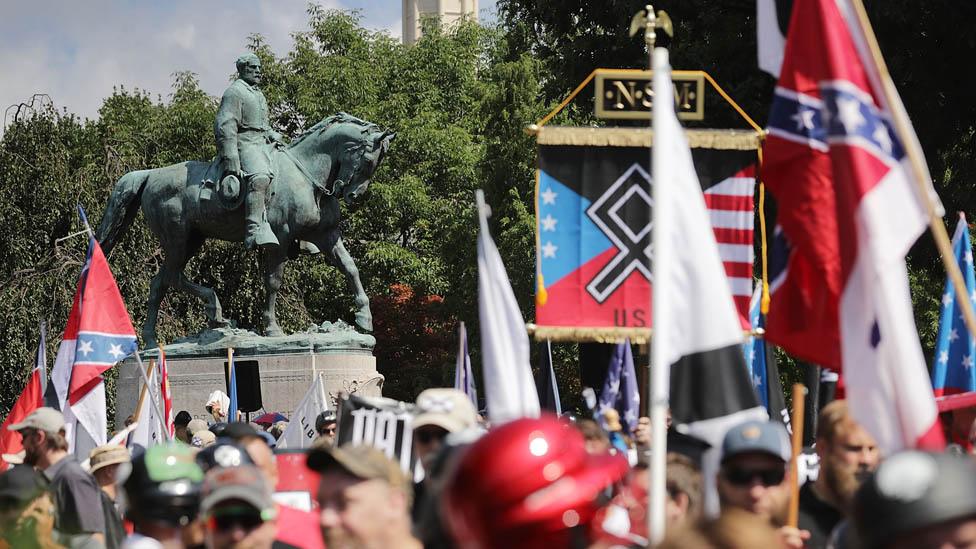

Unite the Right March in Charlottesville, Virginia, in front of a statue of Confederate Gen Robert E Lee

Then there are what philosophers call consequentialist considerations. How does looking at the statue make passers-by feel? This, in turn, will be connected to whether the history still resonates - an ancient statue of some medieval warlord, however bloody and brutal his conquests, probably won't bother anybody. And, arguably, a statue of Rhodes in Cape Town will arouse more offence than one of the same man in Oxford.

Then there are other prosaic but important factors, like the cost of pulling a statue down (might the money be better spent elsewhere?) and the aesthetic value of the statue.

Decisions about how to remember the past are profoundly political as well as ethical. Next to Balliol College is a stone monument, Martyrs' Memorial. It marks the place where, in the mid-16th Century, in the reign of Queen Mary, Protestant bishops were burned. But the memorial itself was only erected three centuries later, in the mid-19th Century, when elements within the Anglican Church were anxious about the growing influence of Catholicism.

Statues and plaques usually occupy public spaces and confer honour and respect. Pulling them down, or renaming buildings, carries symbolic significance. But should institutions do more? Should they make amends in more tangible ways for sins of earlier generations?

Intergenerational justice is a hugely complex topic, not least because over the passage of time it becomes tricky to identify beneficiaries and victims. But Daniel Butt believes that where there is a clear historical continuity with the past, a modern institution has a duty to remedy wrongs, most especially when the impact of these wrongs is still being felt - for example in racial discrimination. He says Oxford's complicity in colonialism confers upon it obligations - obligations which it could discharge in several ways.

"We could think about scholarships in particular areas in the world, we could think about revising our curriculum. But this shouldn't be a decision made by a bunch of mostly white, mostly male academics sitting in an Oxford committee room. This needs to be a process of conversation involving a wide range of different communities - certainly students, but also representatives of the communities with which Oxford has this very complicated past."

Protest against Confederate statues in New Orleans

All Souls College is one of Oxford's most private institutions - its fellows are not required to do any teaching, and can focus exclusively on research. For that reason, few students pass through the lodge which opens on to Oxford's High Street. The college made a substantial donation to Codrington College in Barbados (which teaches theological studies) 30 years ago, but until recently, it has been reluctant to address seriously the awkward provenance of its extraordinary library.

However, a new generation of fellows has begun to agitate for a more honest reckoning with history. Last year several All Souls academics organised a low-profile conference to examine the life of Codrington and his link with the college. Daniel Butt delivered a paper at the conference.

"My view is that they should change the name of the library," he says. "Codrington is beyond the pale in terms of historical injustice. He was involved with slave owning that we now readily condemn as being clearly unjust. I just don't think it's appropriate to honour someone from the past in this kind of way. So I would change the name, and I would at the very least move the statue."

The college will probably not go that far. But it will be taking some concrete steps. It is supporting Codrington College with a five-year grant and has just announced that it will be establishing a fully-funded graduate scholarship to Oxford for students from the Caribbean.

One idea that emerged from the recent conference is a plaque to acknowledge the suffering of the slaves who made Codrington's fortune. Some might dismiss this as a "politically correct" meaningless gesture. But it would be further evidence that the college is at last beginning to square-up to its historical entanglements.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.