I went driving and motorbiking in my sleep

- Published

Sleepwalking can be risky when water, busy roads or cliffs are involved. But sleep-driving elevates the dangers to a whole new level. Consultant neurologist Guy Leschziner describes the case of one of his patients, Jackie, who has been driving in her sleep on both two wheels and four.

Shortly after moving to the UK from Canada, Jackie was lodging with an elderly woman.

"One morning she asked, 'Where did you go last night?'" Jackie says.

Jackie said she had not gone anywhere.

"Well, you went out on your motorbike," the landlady replied.

Jackie was shocked. She immediately asked if she had been wearing her helmet.

"Oh yes, you clomped down the stairs and you had your helmet and you went out," the landlady said, adding that she had been gone for about 20 minutes.

Jackie had no recollection of her moonlit ride because she was asleep at the time. And there were no other clues to indicate she had been out, as she had returned the motorbike to exactly the same place it had been before.

As a child in Canada, Jackie was not the most popular girl to share a tent with in her Brownie group.

"I used to make this sort of growling," she says. "But it wasn't a quiet sort of growl. I think they thought a bear was coming after them. I growled so much and so loud that it frightened them, so they wouldn't have me around."

She was also a handful for the adults supervising the trips.

"I'd get up in the middle of the night and I'd walk down to the river. I'd walk into the woods and you know they couldn't cope with me, so I had to be picked up and taken back home again."

Jackie had been a sleepwalker even before these camping trips.

"I used to walk down the stairs to the lounge, open the door and stand in the doorway where my parents were," she says. "Well, it freaked mother out, but father just took my hand, took me back upstairs and put me to bed and that was it."

This kind of behaviour is very common in childhood.

So are other related forms of behaviour such as sleep-talking, eating in sleep and night terrors - where a child appears to be terrified, screaming and shouting in an inconsolable manner, but wakes with no memory of what has happened. As many adults will know, it can be even more terrifying for the parent.

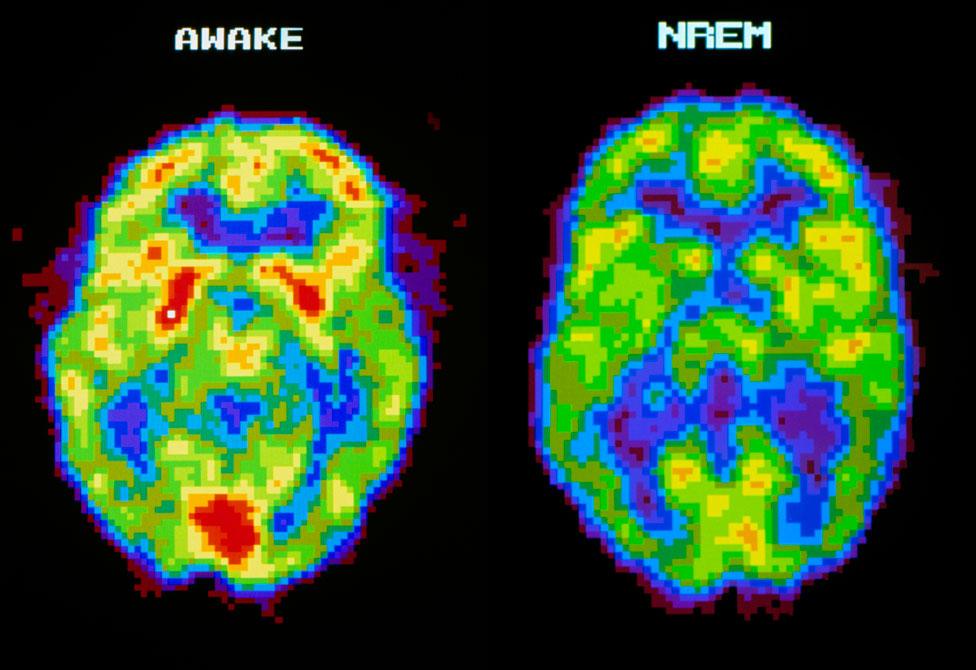

For most children, these events - termed non-REM parasomnias, because they occur outside the dreaming (REM) phase of sleep - slowly disappear over time. But in 1-2% of cases they persist into adulthood.

Jackie responded to the discovery of her motorcycling escapade by giving the keys to her landlady to look after. And with that she thought the problem had been solved.

Find out more

Listen to the second episode of Mysteries of Sleep - on dreaming - on BBC Radio 4 on Tuesday 12 December at 11:00 and again on Monday 18 December at 21:00

Search for #mysteriesofsleep on social media

Wrongly, as it turns out.

Many years later, now living in Seaford, near Brighton, she was leaving her flat in Brighton when some neighbours asked her what she had been doing around 01:30 or 02:00 in the morning.

She told them she had been asleep.

"They said, 'No, no, you were driving out as we were coming home.' And I said, 'I have no idea…' As I had done on my motorbike, I was now in the car driving."

Once again, Jackie had parked her car in exactly the same spot, leaving no clue that might have revealed her nocturnal wanderings.

The news that she had been sleep-driving was not entirely a surprise. Although her sleep-motorcycling occurred in the distant past, she had more recently gone walking around a cruise ship in the middle of night - to prevent an accident she had given her cabin key to a crew member, who locked her in at night and returned it in the morning. She has also been seen walking along the promenade in Seaford in the early hours.

But the thought of driving around the town in her sleep, putting herself and others at risk, greatly alarmed her. It was at this point that she asked her doctor for advice.

What explains this incredibly complex behaviour, apparently arising in deep sleep?

Dolphins and some other animals are able to sleep with one half of the brain at a time

We have known for years that certain animals like dolphins, seals and birds can sleep with one half of their brain at a time, allowing them to swim or fly while sleeping. In humans, this does not occur, but we do now know that sleep and wake can exist in different parts of the brain at the same time. When sleep-deprived, our brains show small areas of the cerebral cortex, the outer surface of the brain, exhibiting "local sleep" - electrical activity consistent with sleep.

Studies of sleepwalkers show that the parts of the brain controlling vision, movement and emotion appear to be awake, while areas of the brain involved in memory, decision-making and rational thinking appear to remain in deep sleep. These findings to some extent explain why sleepwalkers may appear to be awake - with eyes open, speaking and performing difficult tasks like riding a motorbike - but behave in an odd manner, and have no (or only limited) recollection.

A brain in deep sleep should look like the scan on the right - but parts of a sleepwalker's brain will resemble the scan on the left

Like many aspects of sleep, this probably has a genetic basis. Many of my patients at the Guy's Hospital Sleep Disorder Centre report a strong family history of non-REM parasomnias, and preliminary studies have identified areas of the genome that may be involved.

Jackie eventually ended up at Guy's Hospital herself, but in the meantime she had worked out her own ways of managing her condition.

Initial attempts such as hanging a large cowbell from the handle of her front door failed - Jackie's partner Ed is such a heavy sleeper that he was not woken up, and a bell any louder would have woken all the neighbours.

But then Jackie invested in a time-locked safe. Every night she puts her keys in, and the safe does not unlock until 06:00. She leaves a set with a neighbour, in case of emergencies.

This strategy has worked, preventing her from leaving the flat or driving in the middle of the night.

For the most part, behaving like this is inconvenient or embarrassing. People may make phone calls or send texts in the middle of the night, find themselves wandering outside incompletely clothed, or cook meals in their sleep.

"I know one person who every night would get up and sing the national anthem and then go back to bed," says Prof Meir Kryger, of Yale University. But for some, non-REM parasomnias can be more serious, and in rare cases devastating.

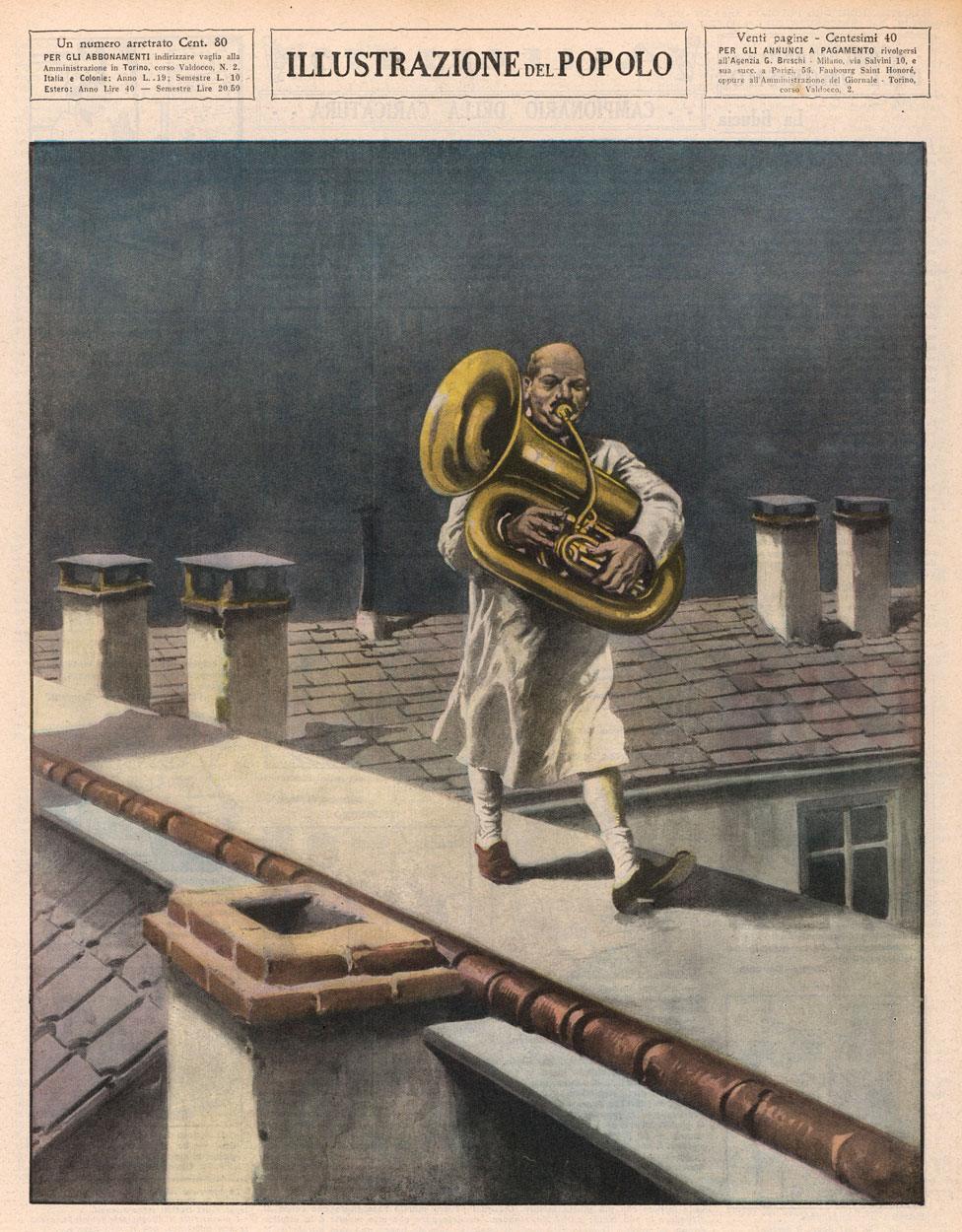

A German sleepwalker playing the tuba in Hettstadt, from an Italian newspaper (1932)

"We worry when a person who has this kind of behaviour gets into a car, if that type of person starts to walk outdoors and if they start to use implements like knives that may be quite dangerous," Kryger says.

For the vast majority of individuals however, non-REM parasomnias are much less dramatic, and managing them is often straightforward.

Anything that results in frequent interruptions to sleep, such as sleep apnoea - a condition that causes the airway to obstruct in sleep - makes this behaviour more likely to occur.

So by improving the quality of sleep and addressing any issues that might cause frequent sleep disruption, things often improve. Occasionally, for more severe cases, medication has a role. Like Jackie, and her time-locked safe, simple practical precautions can make a huge difference.

How to improve sleep quality

Go to bed and wake up at regular times

Avoid alcohol and stress

Limit caffeine

Avoid noises, such as traffic and snoring

Get sufficient sleep

We used to consider sleep and wake to be binary states - that people are either awake or asleep. These remarkable conditions tell us is that this is not the case.

In fact, sleep and wake are at the opposite ends of a continuum, a spectrum of brain activity. Depending where on that spectrum our brain is defines our behaviour, our recollection and our abilities.

So when we are sleep-deprived, and our brains show areas of sleep activity while we are awake, this may explain why we are mentally impaired. And when we are deep asleep, and our brains show certain areas of waking activity, this explains why we undertake these bizarre activities in the middle of the night.

See also:

Sexsomnia: My boyfriend raped his ex 'in his sleep'

The myth of the eight-hour sleep

'LED streetlights are disturbing my sleep'

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.