Greek financial crisis explained

- Published

Protestors clash with riot police in the Greek capital Athens.

Three people, including a pregnant woman, have been killed during riots in Athens.

They died after striking workers set fire to a bank where they worked.

The Greek capital has been gripped by days of violent protests over government plans to slash public spending.

The country is being forced to make massive savings to deal with its financial crisis.

Why are people protesting?

Flowers outside the bank where three people died during the riots.

Many of the protesters are public service workers, whose salary comes from the tax payer.

Others are just ordinary Greeks, angry about how the financial crisis will affect them.

They object to their government's plan to get Greece's economy back under control.

It includes a freeze on public sector pay, raising the tax on fuel, and cutting pensions.

Why is Greece in such a mess?

For years, Greece has been spending money it doesn't have.

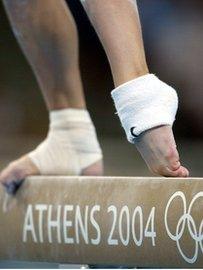

The government there took advantage of the economic good-times to borrow money and spend it on pay-rises for public workers and projects such as the 2004 Olympics.

It began to run-up a bigger and bigger deficit (the gap between how much a country brings-in from tax, and what it spends).

Greece enjoyed high public spending during the boom years, including an expensive Olympics.

After the world economy went bad, Greece suffererd.

Banks started to view it as a country that might not be able to manage its money.

They worried Greece might eventually fail to pay its loans, and even go bankrupt.

To cover the risk, banks started charging Greece more to borrow cash - making the problem even worse.

Eventually the government there went looking for help.

It is now borrowing 110 billion euros (£95bn) from other EU countries and the International Monetary Fund.

That money is being loaned at a much better rate, but comes with tough conditions.

Greece has to promise to cut its budget deficit.

It's those cuts that have led to the riots in Athens.

What does this mean for other countries?

As well as Greece, banks and credit rating agencies are going through their books looking for other bad risks.

That means countries that have a big budget deficit, compared with how much money their economy generates.

The crisis in Greece is being felt in financial markets around the worls

Portugal and Spain are reckoned to be two that could face problems next.

The EU hopes that its bailout will reassure the money markets that their cash is safe.

However, that depends on Greece getting control of the situation and proving it can make the cuts needed.

The UK does not use the Euro currency, but could still be affected.

Its budget deficit is also large, and we could start to appear unattractive to lenders.

UK banks also hold some of the debt of countries such as Greece, Spain, and Portugal.

If they were to go bankrupt, it would mean more problems for Britain's banks.

In the mean-time, there is some good news for holidaymakers.

A fall in the value of the Euro means the pound currently goes a bit further at the bureau de change.