Blurred Lines verdict: How influence was ruled as stealing

- Published

It's taken the best part of two years for a US court to rule the writers of Blurred Lines copied a Marvin Gaye track.

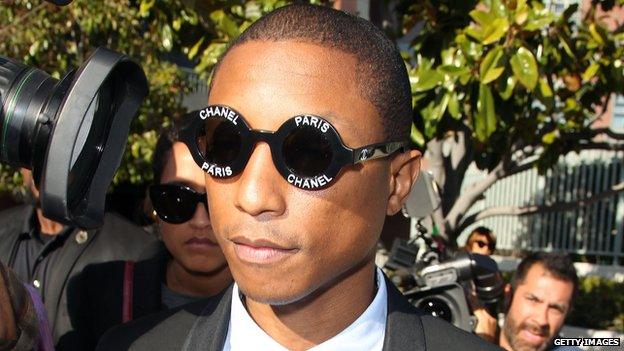

A US jury decided the 2013 single by Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke breached the copyright of Gaye's 1977 hit Got To Give It Up.

As a result, the family of the late soul singer have been awarded $7.3m (£4.8m) in damages.

Now they want the song, one of the best-selling of all time, banned.

Listen to the two songs and see why a US jury came to the conclusion they did, external

Blurred Lines made more than £3m for Pharrell and Robin Thicke and £459,000 for TI

Thicke, Williams and TI, who also features on the track, always denied copying the song and their lawyer said the ruling set a "horrible precedent" for creativity in music.

The outcome over the track, which made $16m (£10.8m) profit, is a rare one in the music industry.

Copyright lawsuits are common in music but few ever make it to trial with disputes usually being settled before getting to court.

This tends to happen because judges decide similarity in songs like melody and tone aren't enough to take to trial and are sometimes unprotectable.

During the trial Williams admitted that Blurred Lines channels "that 70s feeling" and that he looked up to Gaye, but that creating a similar feel or mood with a song isn't copyright infringement.

"The last thing you want to do as a creator is take something of someone else's when you love him," said Williams.

Thicke testified that he had contributed little to the writing of the song

Although claiming to not have much part in the writing of the song, Robin Thicke said he had talked about doing "something like Marvin Gaye's Got To Give It Up" during an interview with Trevor Nelson on BBC Radio 1Xtra when the song came out.

"Marvin Gaye's song is in the minor key. We changed it to major key which makes it more like a country song."

So where did Blurred Lines cross the line between being inspired by Gaye to being deemed to be stealing from him?

The lawyer for Marvin Gaye's family revealed outside court that the case had originally been brought against them

Paddy Gardiner, a music lawyer at Michael Simkins LLP, spoke to Newsbeat when the trial started.

"The difference is between styles of music and people being influenced by other artists," he said.

"And then situations where an artist will deliberately or subconsciously take music or lyrics and that's where it can cross the line into a dispute."

Howard King, who represented Thicke and Williams, spoke about how artists needed more creative freedom.

During opening arguments, he told the jury: "We're going to show you what you already know; that no-one owns a genre or a style or a groove.

"To be inspired by Marvin Gaye is an honourable thing."

The judge told the jury they couldn't just listen to the songs and make a decision.

Sections of sheet music were compared in the court room and also saw Robin Thicke playing a selection of songs on a piano in the hope of proving that the musical structures of the two songs were different.

Rulings can be made if a certain amount of bars in two songs are thought to be too similar.

Marvin Gaye's daughter Nona Gaye spoke after the trial in Los Angeles

Gaye died in April 1984 leaving his children the copyright to his music.

"Right now, I feel free," his daughter Nona told reporters after the ruling.

"Free from... Pharrell Williams and Robin Thicke's chains and what they tried to keep on us and the lies that were told."

Although the Blurred Lines trial ended in a financial payout, Paddy added copyright cases don't always end in money changing hands.

"There can be an injunction, which means the later track can't be used," he explained.

"Also in some cases the writer can be credited on the newer track which can bring in royalties."

Sam Smith said he was "not previously familiar" with Tom Petty's track

That was the outcome in a recent case between Tom Petty and Sam Smith over Stay With Me.

The American songwriter was given a song-writing credit after claiming there was a strong similarity between his 1989 track I Won't Back Down and Smith's 2014 single.

A spokesman for Smith said the singer "acknowledged the similarity", but the likeness was "a complete coincidence".

It was "amicably" agreed Petty and his collaborator Jeff Lynne would be credited as co-writers of Stay With Me.

Naughty Boy told Newsbeat that making music similar to an old track can happen completely by mistake

Katy Perry, Naughty Boy, Jessie J and Lady Gaga have all been caught up in a recent rise in accusations of artists copying others.

Marcus O'Dair, lecturer in popular music at Middlesex University, told Newsbeat there are reasons for the increase.

"This is just something to do with social media, that in fact there aren't more cases than before - they are just more public," he says.

"Of course there is also the fact that there is a limit to the number of chord sequences and melodies that actually work and connect."

Follow @BBCNewsbeat, external on Twitter, BBCNewsbeat, external on Instagram and Radio1Newsbeat, external on YouTube