Five facts you should know about the Northern Ireland election

- Published

Northern Ireland's elections are quite different compared to the ones held across the rest of the UK - in England, Scotland and Wales.

In fact some of the campaign issues were put to bed in the rest of the country almost 50 years ago.

And although every party wants to "win", they all know they'll never be fully in charge. Polling takes place on Thursday 5 May.

Here are five things to know about the election in Northern Ireland.

Green and Orange

For 30 years there was fighting in Northern Ireland between two sides of the community.

Those who want to break Northern Ireland's links to Britain ("Green") and those who want to stay part of the UK ("Orange").

The Green/Orange divide is sometimes referred to as Catholics v Protestants but that's not totally accurate.

When it comes to politics you'll most often hear the two sides referred to as nationalists (Green) and unionists (Orange).

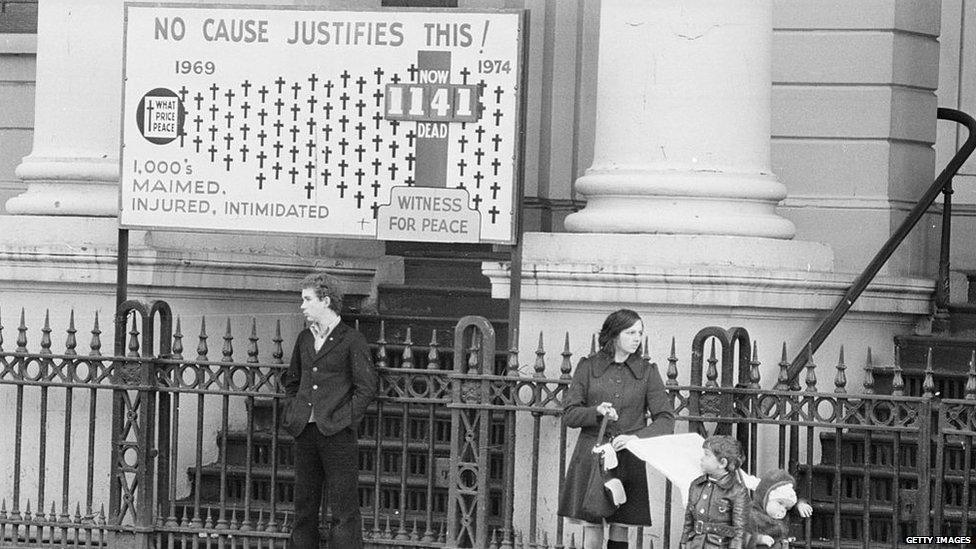

The Troubles caused thousands of deaths

The fighting, known as "the Troubles", affected most families in some way. 3,000 people were killed.

It's still an issue that dictates how a large number of voters make up their minds.

For example, a unionist may care deeply about education, but is generally unlikely to vote for a nationalist party, even if they agreed with their policies on education.

It's the same the other way around. In other words, there's very little that would trump the green/orange issue for a lot of voters.

Some parties like Alliance and the Green Party (That's "green" as in the environment…) identify as being neutral.

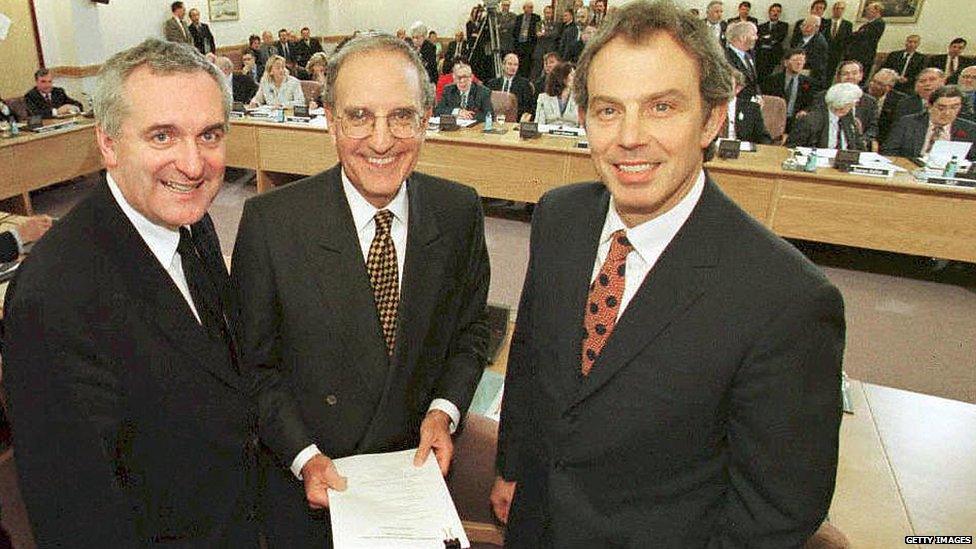

Generation Good Friday

Some people voting won't remember this picture of Prime Minister Tony Blair (R), US Senator George Mitchell (C) and Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern (L) signing the agreement

The Troubles ended in 1998 with the world famous Good Friday Agreement and Northern Ireland has become quite peaceful since then.

This year the babies born that year have been turning 18, which means for the first time there is a section of the community who have a vote but do not remember the Troubles.

Many of them say they will vote based on "issues" rather than simply along Green/Orange lines.

It remains to be seen what impact Generation Good Friday has.

The big issues

Protests both for and against abortion take place regularly in Northern Ireland

Some of the hot topics in Northern Ireland are almost never discussed in the rest of the UK - perhaps most famously abortion and same-sex marriage.

Abortion is only permitted in Northern Ireland to save a woman's life or if there's a serious and permanent risk to her mental or physical health.

Many young voters say they want to see the country's laws brought into line with the rest of the UK where abortions have been legal since 1967. But not everybody does and religion has a big part to play.

In the 2011 census 82% of people identified as Christian. That's considerably higher than the average in Britain which was 57%. Only one party running in this election is calling for full legalisation of abortion (the Green party).

Watch Newsbeat's documentary: No Gay Marriage Here: The Northern Ireland Story, external

The biggest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly is Christian and called the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). They have also been the main group to block same-sex marriage, meaning NI is the only part of the British Isles where gay couples cannot marry (civil partnerships are recognised).

NI also has the highest rates of suicide in the UK, so mental health is another issue many young voters feel strongly about.

Average wages are among the lowest of anywhere else in the UK and the Northern Ireland economy has not been recovering as well from the recession.

Working together

Northern Ireland's main government buildings are in the grounds of Stormont Estate

The party that wins the most votes doesn't get to be in charge like they would in other parts of the UK. In Northern Ireland there is a system called mandatory coalition which means power (and the top jobs in government) are shared among the biggest parties.

The country is led by the first and deputy first ministers. Both roles are equal despite the titles.

The party with the most votes (last time it was the DUP, a unionist party) appoints the first minister and get first pick at some of the top government posts. For example, they chose to be in charge of finances.

The second biggest party (last time it was Sinn Fein, a nationalist party) appoints the deputy first minister then chose some roles - last time that included education.

And so on, and so on.

Mandatory coalition was designed to make sure there was a balance in power and that each side of the community felt they had proper representation.

But it means there can be very little done without total agreement from both sides. And in Northern Ireland that can be easier said than done.

It's led many younger voters to describe the Assembly as "stale" with too much time spent bickering rather than decisions being made.

However, others say the system is much better than how things were before the Good Friday Agreement.

There are *lots* of parties

Fewer people live in the whole of Northern Ireland (1.8m) than in Manchester (2.5m). But that doesn't stop them having lots of choice.

This year 19 parties will be represented on the ballot paper. There are also 23 other candidates running independently.

One reason is that opinions can differ within the Green/Orange communities.

For example some unionist parties will see themselves as more liberal than others.

There are also parties concerned mainly with say, animal welfare or the legalisation of cannabis.

There are 18 constituencies, with six MLAs (Members of the Legislative Assembly) voted in in each. That means a total of 108 MLAs take their seat at Stormont.

See all the parties that are running in your area.

Find us on Instagram at BBCNewsbeat, external and follow us on Snapchat, search for bbc_newsbeat