The future of contraception? Four ways it could change for you

- Published

More than one in four women in the UK take the contraceptive pill.

For lots of people it's a convenient way to help prevent pregnancy, and it can ease problems like acne and painful periods too.

But it doesn't suit everyone. A recent Danish study even suggests the combined pill could be linked to depression.

Tuesday night's Radio 1 and 1Xtra Stories explores the future of the pill and what could come next.

Fertility apps

Apps are now available to help women track their own fertility cycle.

These range from a simple calendar to more complex versions that require users to take their temperature every day.

"It takes me 30 seconds a day and tells me when I'm fertile and when I'm not," explains journalist Holly Grigg-Spall, who spent years researching hormonal contraceptives for her bookSweetening The Pill.

"And when I'm fertile I can either choose not to have sex, or I can use a condom."

She thinks more women will start using fertility apps as technology improves.

"Eventually it'll be the technology industry that will step up and provide hormone-free alternatives that women can use to learn more about their bodies and avoid pregnancy very effectively."

But Dr Sarah Hardman, deputy director at the faculty of sexual and reproductive healthcare, thinks fertility trackers are less reliable than other methods because women have to monitor themselves every day.

"The hormonal methods and the copper IUD offer really effective methods of contraception that women don't have to think about day in, day out.

"[Non-hormonal] methods are not as robust. If women want to be absolutely certain that they have the most effective methods, they should be discussing that with a doctor so they can talk through the pros and cons."

A new type of pill

The pill is just one of 15 types of contraception, external available in the UK.

There are two types of pill.

The combined pill contains two hormones, oestrogen and progesterone, which women naturally produce.

Increasing the amount of these hormones in a woman's body stops the ovaries releasing an egg and thickens the lining of the womb, making it more difficult for a fertilised egg to grow.

But some women can't take contraception that contains oestrogen - for example, because they have high blood pressure, or are overweight.

That's why many newer pills contain only progestogen - they're also known as the "mini pill".

Both types are more than 99% effective at preventing pregnancy if used properly, although they don't prevent the spread of STIs.

Doctors say women might need to try out a few before they find what suits them.

"It's really all about making choice," says Dr Hardman.

"If they have a side effect with one hormonal method it doesn't necessarily mean they're going to have the same side effect with another."

The male pill - or will it be a nasal spray?

The male pill has been promised for almost as long as the female pill has been available in this country - 55 years.

But concerns over side effects, and a lack of funding, have meant it's never been released.

Now researchers from the University of Wolverhampton reckon they might have the right formula, external.

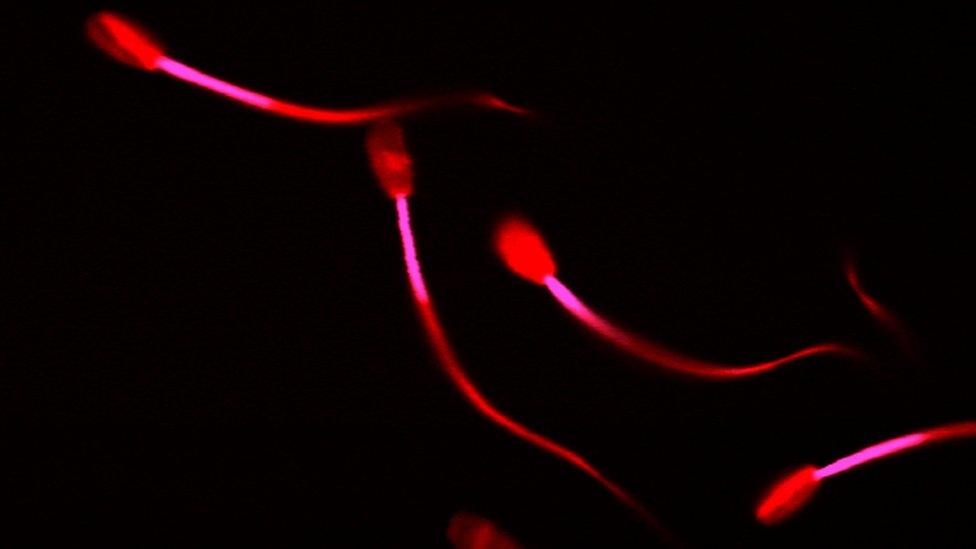

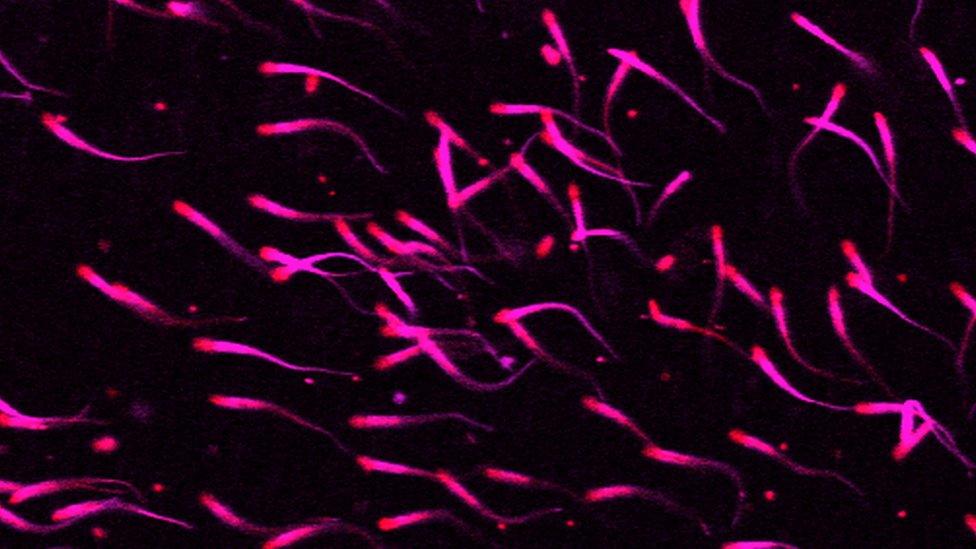

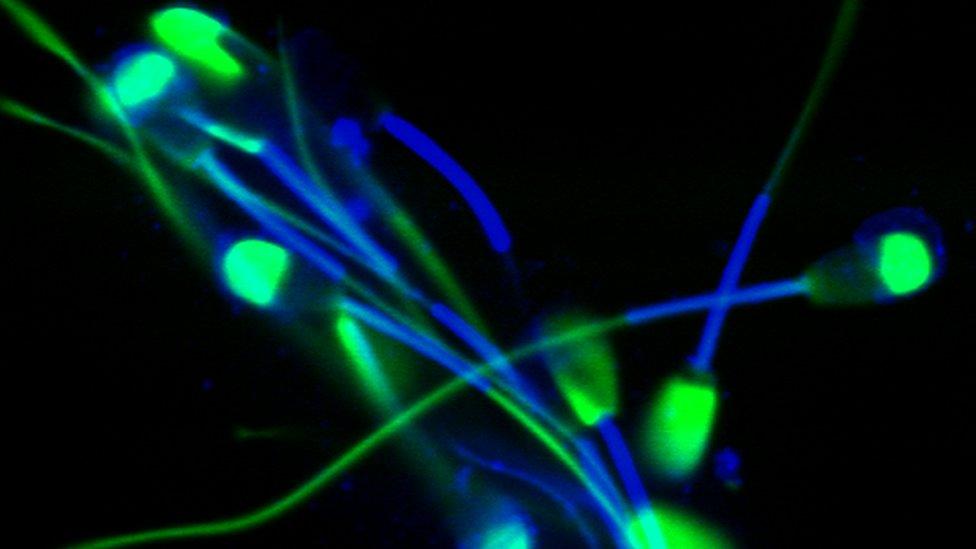

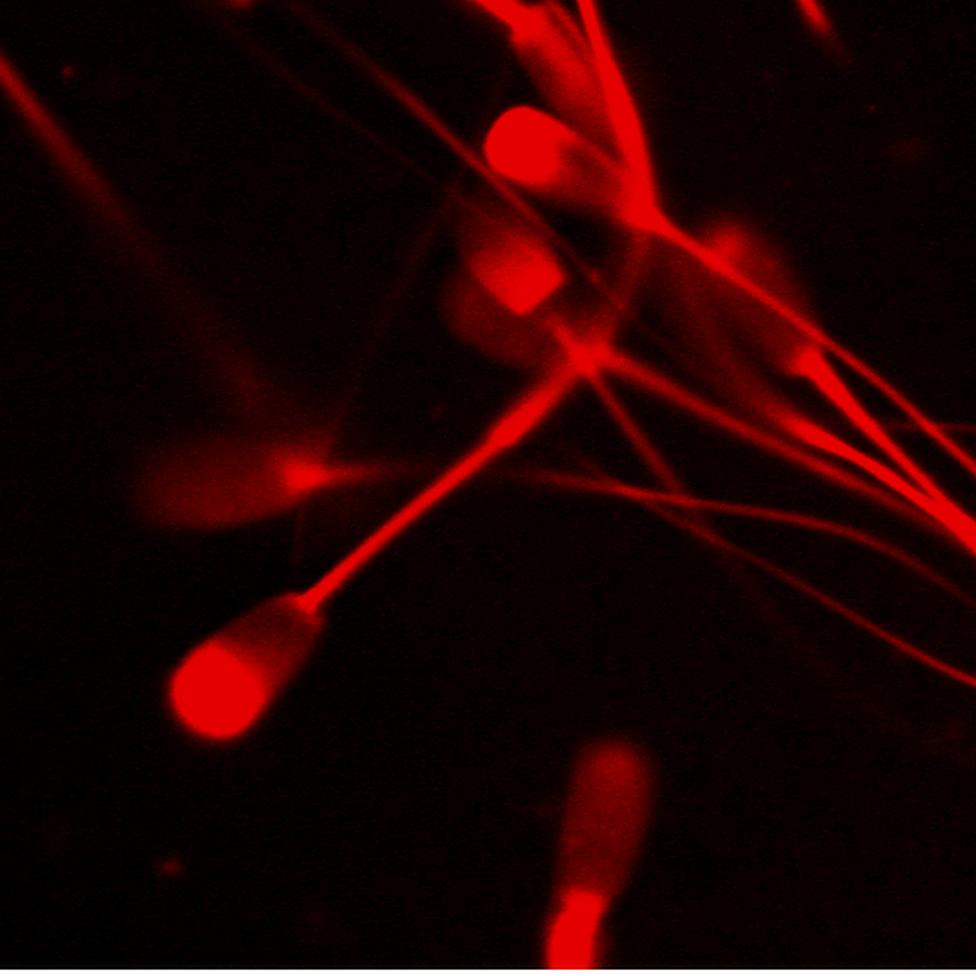

They've developed a peptide - or protein - which slows down sperm.

It could be made into a male pill, nasal spray or cream, which men would take a few hours before sex.

"It just gives couples another choice, but it's not going to be suitable for everybody," says Dr Hardman.

"It would rely on trust as well, and women having confidence that their male partner was actually using their contraception properly."

The University of Wolverhampton researchers claim their breakthrough could see a male contraceptive on the market within 10 years.

But Dr Hardman thinks that's optimistic.

"There are lots of studies going on at the moment, but we're certainly not there yet."

The male injection

A recent trial of a male contraceptive injection found it 96% effective in preventing pregnancy.

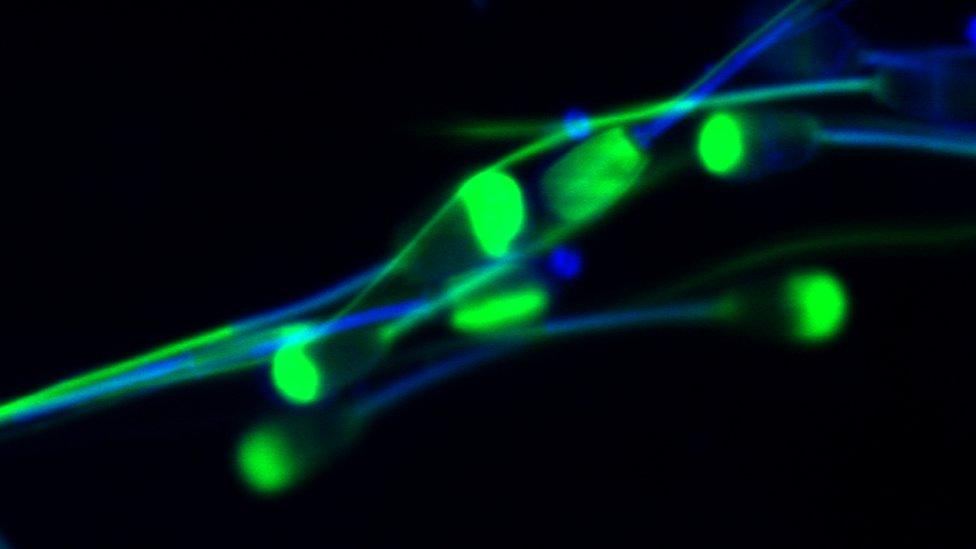

Two hundred and seventy men took part. They had two hormone injections (progesterone and a form of testosterone) every eight weeks, and were monitored for up to six months until their sperm count fell to under a million.

The trial was halted because of concerns over side effects like mood swings and acne.

But researchers say they'll continue to work on alternatives.

"The main thing we found out from this study is that this combination of hormones did switch off men's sperm production in almost every single man tested around the world," says Professor Richard Anderson from the University of Edinburgh.

"I don't think a male pill or injection would ever become the number one bestseller, but there's certainly a place for it in adding to the choices that couples have to find something that really works for them."

You can find more information about sexual health and relationships on these BBC Advice pages.

Find us on Instagram at BBCNewsbeat, external and follow us on Snapchat, search for bbc_newsbeat