Hong Kong protests: What do young people want?

- Published

Pro-democracy protestors attending a rally in Hong Kong

As evening falls on the Kowloon side of Hong Kong, a queue of young people line up outside a small hardware store.

It's become a popular outlet for protesters to stock up on gear needed for demonstrations. Boxes of hard hats and goggles spill out of the doorway and into the streets.

Chris - a 22-year-old graduate whose name, like the others in this story, has been changed for safety reasons - is a customer. He upgraded his half-face gas mask for an industry standard full-face respirator - the protesters' gas mask of choice. He is a member of a 30-man team of battle-hardened protesters working in unison during heated street battles.

"There are many roles: fire fighters who put out tear gas, first-aiders, people who build the defence lines and runners who go up front to look out for the cops," he tells Radio 1 Newsbeat.

Anti-extradition protestors at Chater House Garden in Hong Kong

Hong Kong used to be a colony belonging to Britain.

It was returned to China in 1997 and was guaranteed certain freedoms not enjoyed in the rest of China.

Read more: Hong Kong profile

The territory has been rocked by 11 weeks of anti-government protests that started as opposition to a now-suspended extradition bill, which would have allowed suspected criminals to be sent to mainland China for trial.

It has transformed into a civil-disobedience campaign, with weekly demonstrations sometimes ending in violent clashes between fringe protesters and police.

Protesters are calling for the complete withdrawal of the extradition bill, an independent inquiry into police use of force and greater democracy.

Last week two mainland Chinese citizens suspected of working as undercover police officers were tied up at a mass protest which paralysed Hong Kong's international airport.

"People lost control of their emotions. Too much noise and people. It turned a bit chaotic," says Chris, who was there.

Protesters describe their ransacking of Hong Kong’s Legislative Council one month on

"The older generation didn't take their responsibility so we are forced to," says Daniel, a Hong Kong-born British national and protester.

"It's only people between 15 and 30 doing this. What we are doing is protecting ourselves and protecting our next generation."

Earlier in the summer he watched news of the anti-extradition protest from the UK and returned to Hong Kong to join the movement.

"If we are not going to do it, no-one is going to do it," he says, dressed in black and armed with an umbrella - a symbol of the 2014 Hong Kong protest movement.

Like thousands of protesters he has taken part in clashes between police and demonstrators, sometimes throwing tear gas canisters back at the police.

Tanks have been seen in Shenzhen, a Chinese city near Hong Kong

On 1 June hundreds of protesters stormed Hong Kong's parliament. The government building was ransacked, with some smashing computers, destroying documents and vandalising Hong Kong's emblem.

"It was really messy in there - everyone wanted to smash TVs, do graffiti everywhere. It felt chaotic but it was kind of organised at the same time," says Daniel.

Some protests since have become increasingly violent as demonstrators demand greater democracy.

"The British government can't really do anything, they can't take Hong Kong back. They should do their best to make them (China) do what the promise was. Give us a right to vote," says Daniel.

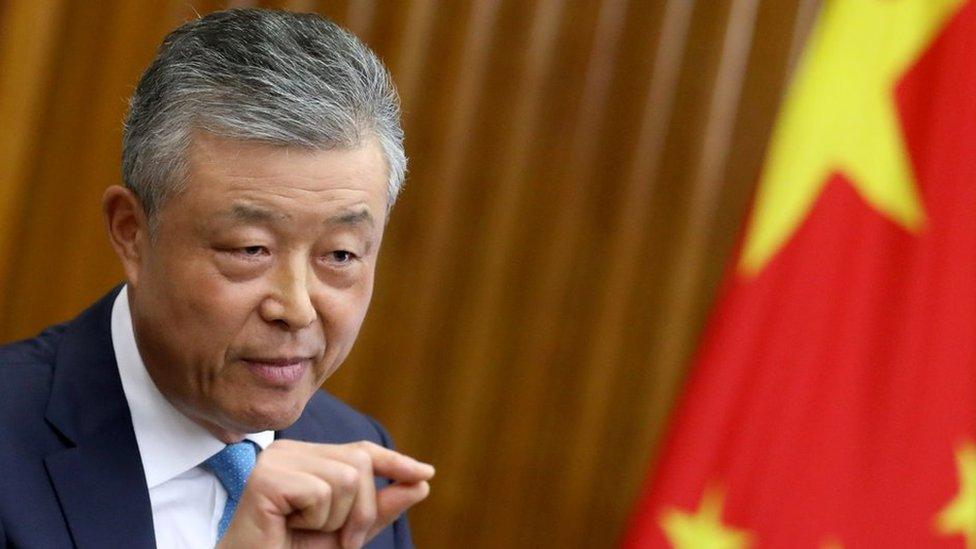

On Thursday, China's ambassador to the UK said Beijing would not "sit by and watch" if protests became "uncontrollable".

He urged Prime Minister Boris Johnson - who said he backed Hong Kong's protesters "every inch of the way" during the Conservative leadership campaign - to take "great caution" when dealing with the former British colony.

"I think some politicians in this country… still regard Hong Kong as part of the British empire," said Liu Xiaoming, China's envoy to the UK.

Police ready to confront protestors on the streets of Hong Kong

Police say that more than 700 protesters have been arrested since the movement began. Daniel fears he could be too.

"They can come to your house, knock on the door and arrest you for something you did years ago," he says.

"Everyone is scared every day. Will I get arrested today, tomorrow, the day after?"

Society 'falling apart'

Professor Francis Lee from the Chinese University of Hong Kong says young people are "fighting for a just and fair society that they perceive to have been falling apart" over the past decade or so.

His research into the protesters' motivations found that 80% of participants believed the protests should continue if the government did not make any concessions. Approximately half of those questioned supported further escalations.

On Sunday more than one million protesters were on the street in largely peaceful protests - which Professor Lee thinks shows the ability of the movement to "adjust and self-correct".

"Why are the protesters so anti-China?" questioned pro-Beijing legislator Regina Ip.

"I think they have been brainwashed by many anti-China teachers. They feel threatened by the mainland because of its economic rise," she said.

"Hong Kong is paying a big price for the extradition bill. All the pent-up anger, all the long-standing problems of wealth gap and housing problems."

Protestors have been gathering at Hong Kong airport to disrupt flights

Some protesters are concerned about the use of violence but emphasise the need to remain united in opposition.

"I would not physically pick up a brick and throw it at a police station, but I wouldn't stop others from doing this," says Lyla, a humanities university graduate.

"We are trying not to create all the fragmentation. It's is important not to leave anyone behind. Not to make anyone feel isolated."

China has warned that the military could be used to stop the protest movement, but that's only supposed to be possible in extreme circumstances:

If China declares an all-out state of emergency or war in Hong Kong

At the request of the Hong Kong government

For the "maintenance of public order and in disaster relief"

On Thursday videos emerged online of thousands of Chinese military personnel stationed in a sports stadium in Shenzhen - a Chinese city just four miles away from Hong Kong.

"It would become like the Vietnam War if the People's Liberation Army (PLA) comes in and no other countries are willing to help us. There are people who are ready to fight that war when it comes," says Chris.

Police at Hong Kong airport during demonstrations

"It takes the military 10 minutes to get to Hong Kong. But it takes us less than 10 minutes to get home," says Daniel.

"We'll just get on with our summer holiday like how it should be and we'll just let the economy collapse.

"That's the only way we can win. Because the Chinese economic system really relies on Hong Kong.

"If we burn they'll burn with us."

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external, Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

- Published4 September 2019

- Published21 August 2019

- Published15 August 2019

- Published28 November 2019

- Published15 August 2019