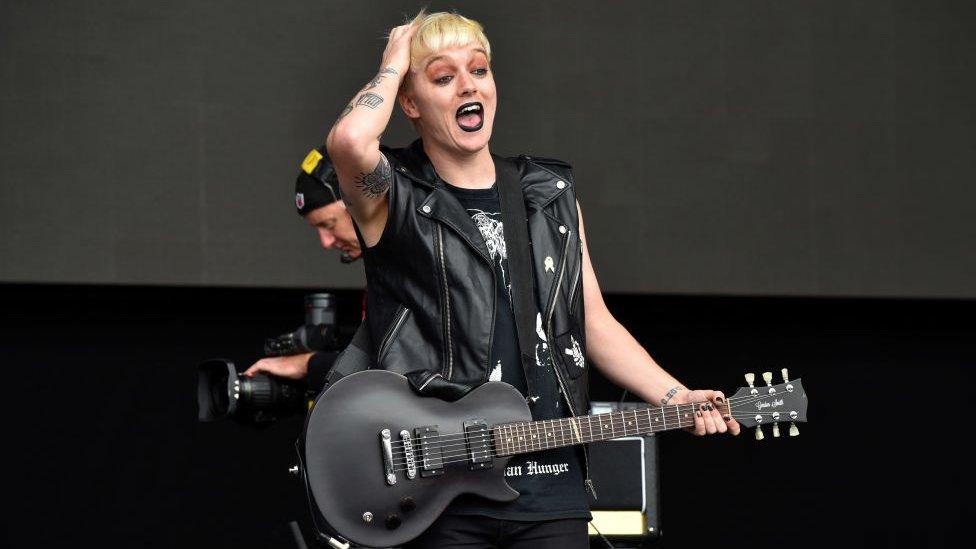

Creeper guitarist: 'I worked on the album from a psychiatric ward'

- Published

Last year Ian Miles went into a psychotic episode and was committed to a psychiatric hospital. Now, he's promoting new music with his band, Creeper, who told Radio 1 Newsbeat how they came through the "worst year of their lives".

I'm on a Zoom call with Ian and Creeper's singer Will, and Ian is talking about the day he was sectioned.

"I was told by this underground cult that my area was Southampton, so I was to go out and eradicate religion in my area. That was what happened that day - I was on a mission to help the cause."

Understandably, a lot of people find it difficult to speak about the experience to close friends, let alone the media.

"If it was something I was uncomfortable with you printing I wouldn't be saying it," Ian laughs when I ask if there's anything he doesn't want me to include in this piece.

"There's a lot of misinformation out there about mental health and I feel like people should be educated," he says.

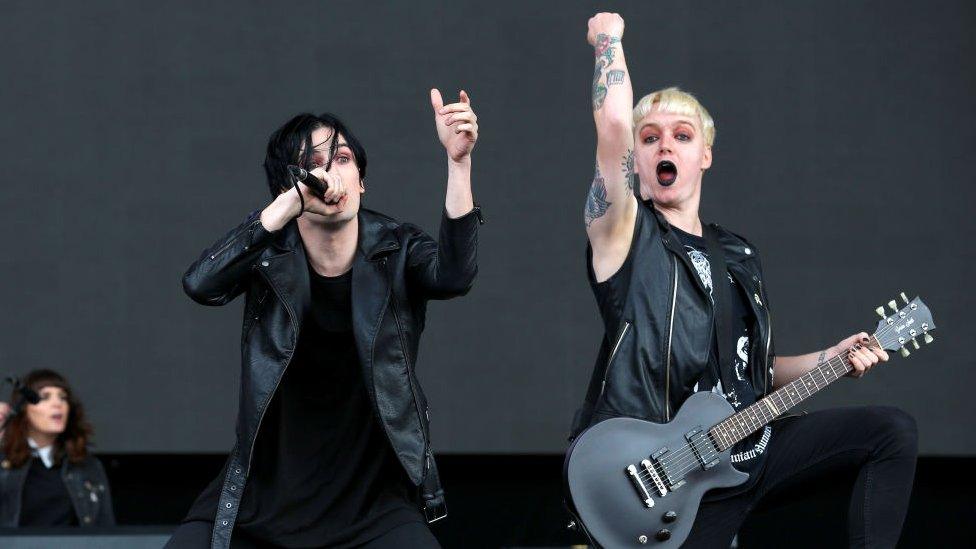

Will and Ian on stage together at Download festival in 2017

If you're new to Creeper, they're quite hard to pin down.

They describe themselves as "more of an art project than a band", with elements of punk and pop as well as horror movie aesthetics and a lot of theatrics.

It can get pretty dark and, listening to the music, it's clear the band have experience wrestling with demons.

Ian says that although he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder "a long time ago", he didn't really appreciate how bad things had got until it was too late.

"There was all sorts of stuff going on. Like I thought I could kill people by blinking at them.

"I thought religion and the police were collecting money and handing it up to the government and MI5 to buy nuclear weapons to end the world.

"And so I thought there was an underground cult that were looking to shut down religion - I was trying to fight the good fight."

Creeper's debut album - Eternity, in Your Arms - made the top 20 when it was released in 2017

Ian says it's taken a lot of treatment and "the right cocktail of drugs" for him to even remember his breakdown.

"One of the hardest things about it was then effect it had on the people around me - and it's only recently I've realised that."

One of those people was Will - who was not only dealing with his friend being sectioned, but also grieving the loss of a family member.

Will says although he was an "anxious mess" he had no choice but to keep working on the album.

"At the time, basically the band was going to break up if if we stopped... we had to deliver.

"So Ian's wife brought a guitar into the hospital and I would FaceTime him from a piano and we would try and write like that.

"I remember trying to find a chord for a song and, at the time, Ian was still really unwell and believing all these delusions, but it was really funny because he could still just turn all of that off for a second to help me work out what chord I needed."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The album, called Sex, Death and the Infinite Void, closes with the heart-wrenching track All My Friends - a song that Will wrote for Ian.

"I can't even listen to it. I find it very, very real and very difficult," Will says - explaining that he had to be persuaded to put it on the album.

They both say they've got "no idea" how they are going to perform it live.

"I'm just glad it's a piano ballad," laughs Ian, "so I can go off stage and find a bit of space to myself."

Will says there is a 'very real pain' on the band's new album

Ultimately, Will says he's glad the song made it onto the album because it helps "normalise" conversations about mental health.

Ian agrees, and he knows first hand how alienated you can feel when you're having a crisis.

"When you come round from a psychotic episode, it does make you question yourself a lot, because all you see in movies and media and computer games is that psychotic people are killers.

"And then on Halloween you've got the psycho clown hospital or whatever and it makes you think to yourself, 'am I in that category?'"

'I realised I shouldn't be in denial, I should just be open about it'

He thinks society is often reluctant to engage with what's seen as the "scarier" side of mental health.

"Yes it's important to talk about depression and anxiety, but it's also important to talk about psychosis and OCD, and all of the harder subjects to talk about.

"Children should be made aware at a young age that if they do have these issues they're not alone and that there are people older and younger, from different classes and ethnic backgrounds, that all go through the same stuff.

"I feel like the more people are aware of that, the less alone they'll feel."

If you are experiencing emotional stress, help and support is available here

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external, Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

- Published20 May 2020

- Published22 January 2020

- Published17 March 2017