Akala: Why we need more black, working class period drama

- Published

The UK loves its costume dramas.

Bridgerton was Netflix's "biggest series ever", 73 million households have watched The Crown since it began and Downton Abbey's getting its second film spin-off this Christmas.

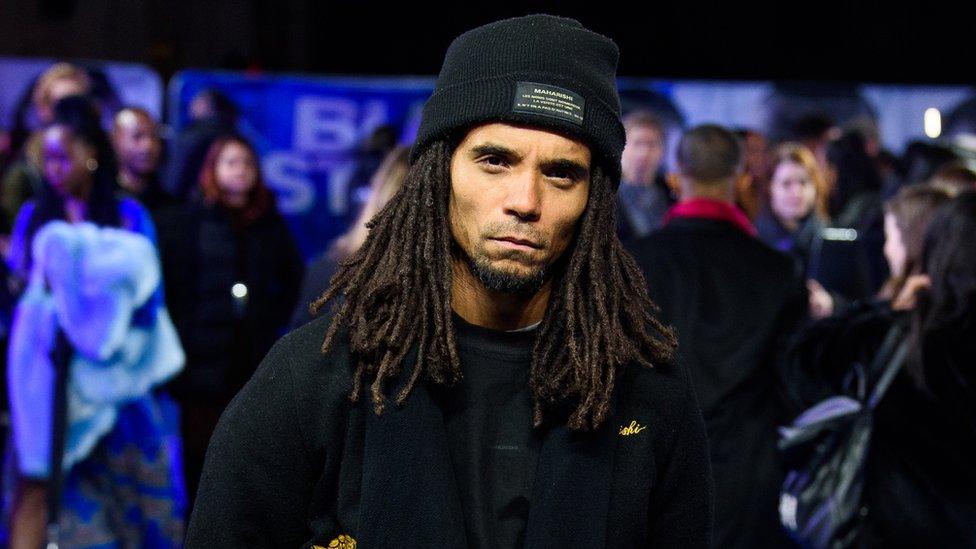

But according to artist, writer and social commentator Akala, they're all missing something.

"Most of the period drama we get is usually focused on elites. Kings and queens and 'great men' - so to speak," he tells Radio 1 Newsbeat.

"I want people to be able to imagine and historicise a black experience, specifically a black working class experience, and hopefully relate to that."

Although Bridgerton was mostly praised for its racially diverse cast, it was still focused on elites.

Akala's first novel, The Dark Lady, aimed at teens and young adults, follows the story of Henry - a 15-year-old pickpocket, living in a notorious slum in Elizabethan England, around the time of Shakespeare.

He's black, and working class, and he finds he has secret powers.

'Were there black people back then?'

Akala isn't new to tackling this sort of thing for younger audiences.

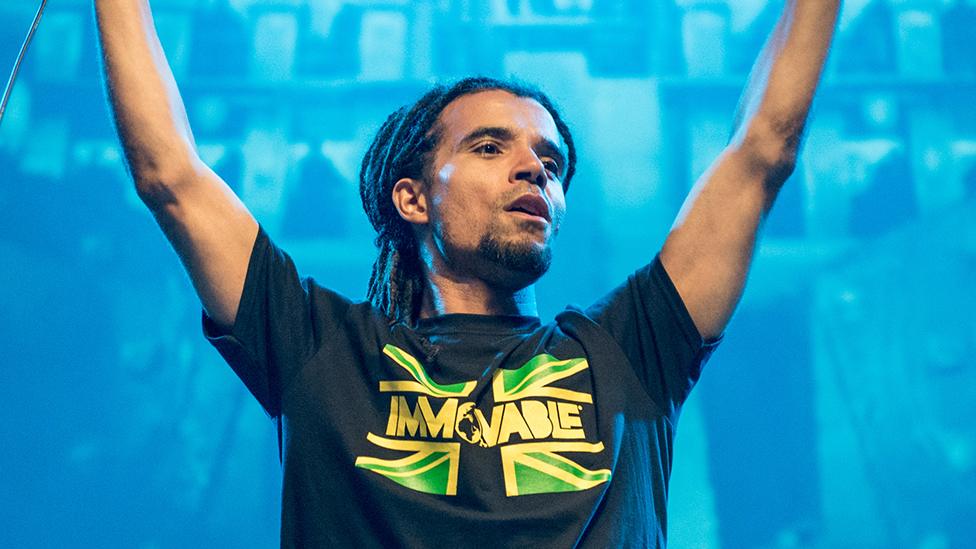

In 2009, he co-founded The Hip-Hop Shakespeare Company, which translates the writer's famous plays into modern rap.

More recently, he was doing work on Shakespeare in schools, when a student asked him: "Were there black people back then?"

"That, in my view, is because there's been so little period drama about the subject," he says.

"Whether that's TV or writing. It's a deliberately cultivated ignorance, globally."

Akala started rapping in the early 2000s, and even won a MOBO

Akala feels that most people get their "sense of the past" from entertainment, and that the "black presence" in Elizabethan England is not well known. He hopes his novel will "surprise people".

Although it's commonly thought that black immigrants mostly arrived in Britain after the war, you could have met people from Africa in London streets in Shakespeare's day.

Employed often as servants, but also entertainers, there were hundreds of black residents.

We know they lived, worked and married into British communities.

'London similar to 500 years ago'

The original Shakespeare theatre was built in 1599, it has since become Shakespeare's Globe theatre

Although it's not "well known", Akala says the world in the book might feel familiar to some because "London hasn't changed that much".

"In terms of Dickensian inequality, in terms of the haves and have-nots, living cheek by jowl, London is really quite similar to what it was 500 years ago."

"I think lots of people will be shocked how much a teenager living in a slum then would have faced some similar challenges to kids living on a council estate today."

Filling this "gap" in black history will help people "understand their place within the world", he says.

"I want people to understand the way the world works, the way power works."

He says he wasn't brought up to "believe the police were just there to protect everyone."

"My parents gave me a certain level of understanding of the way the world worked, I wasn't surprised. I was able to mentally process some of those experiences."

Akala has spoken previously about being disproportionately pulled over and searched by police

Race, class, and their impact on society is something Akala is often called to speak on. His previous book, Natives, was a non-fiction commentary on these topics.

Although The Dark Lady is a fiction book, Akala didn't feel the need to separate his political views.

"The idea that there's this neutral way of presenting art that isn't from a particular class position or doesn't have a particular view of the world - I don't believe is true.

"People have tried to present one view and one section of society as the default in the past, and then say anything else is political correctness gone mad. It's nonsense."

"I've taken my own experiences growing up, my own view of the world and some of my own politics. I don't make any bones about that.

Follow Newsbeat on Instagram, external, Facebook, external, Twitter, external and YouTube, external.

Listen to Newsbeat live at 12:45 and 17:45 weekdays - or listen back here.

Related topics

- Published9 June 2020

- Published22 January 2020

- Published21 January 2021

- Published25 December 2020