Lady Gaga fixes me with a withering stare.

I’ve just asked her a simple, but apparently impertinent, question: "What’s the perfect length for a pop song?"

"Whatever length the artist wants is the perfect length," she intones.

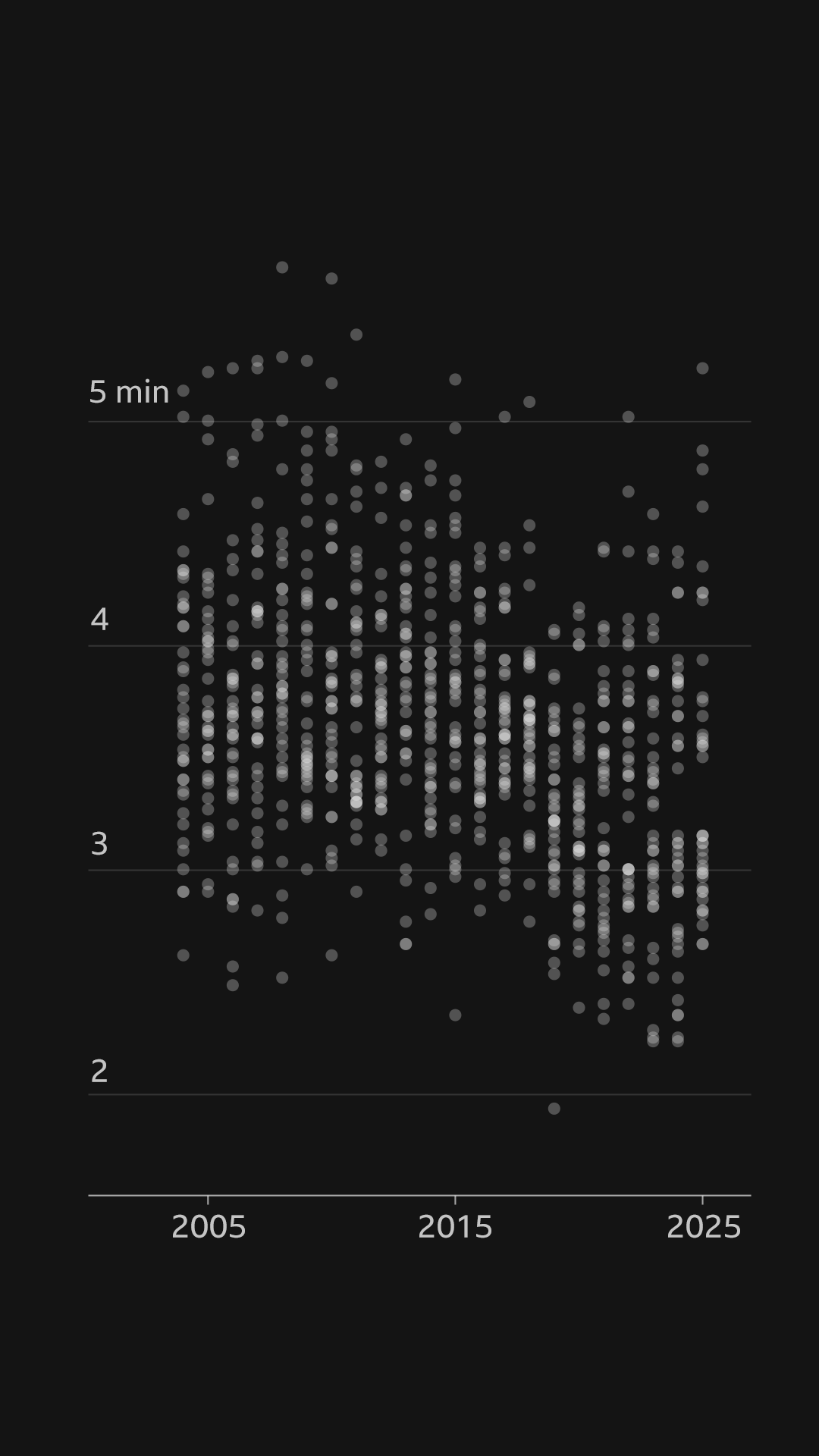

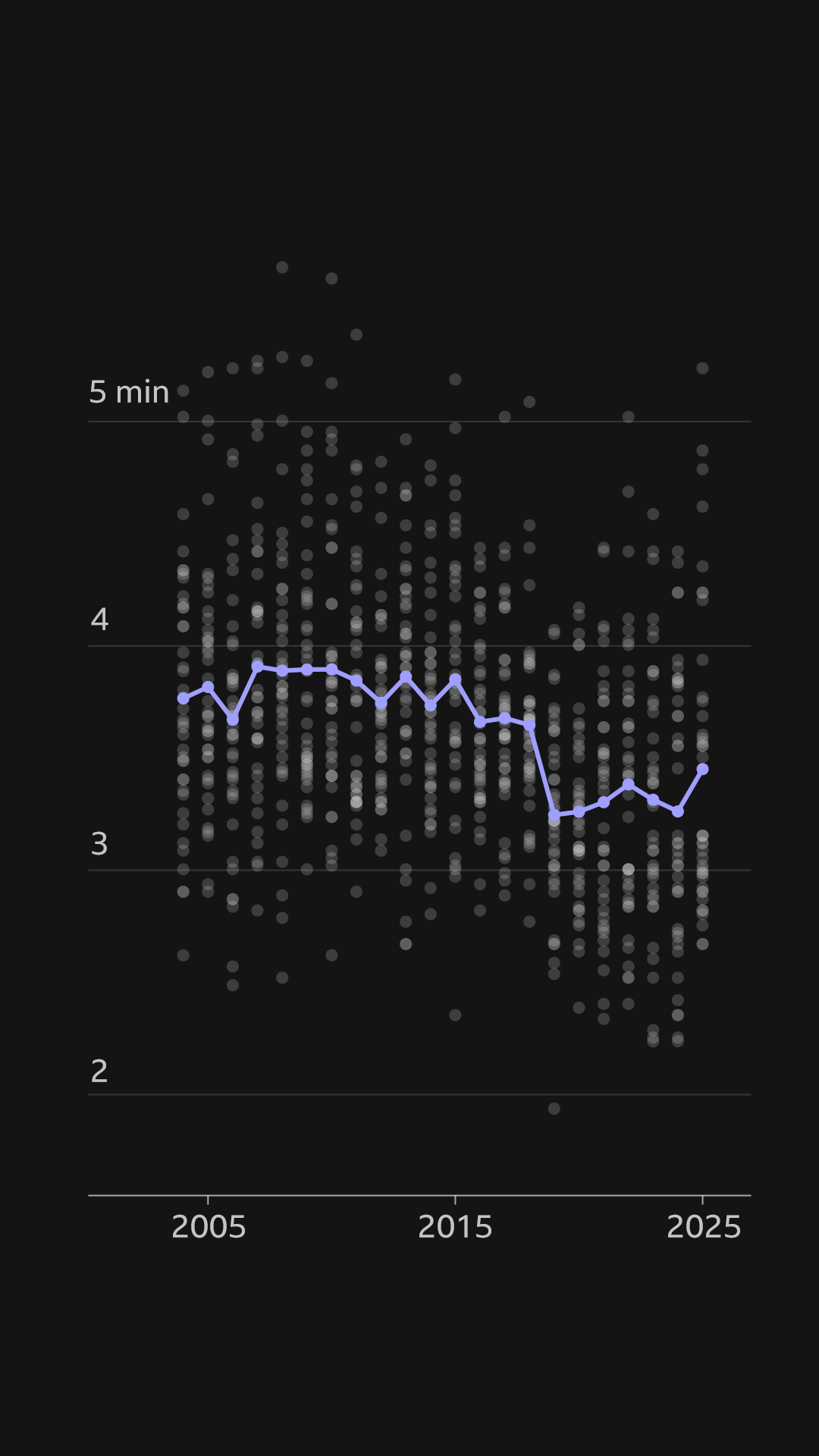

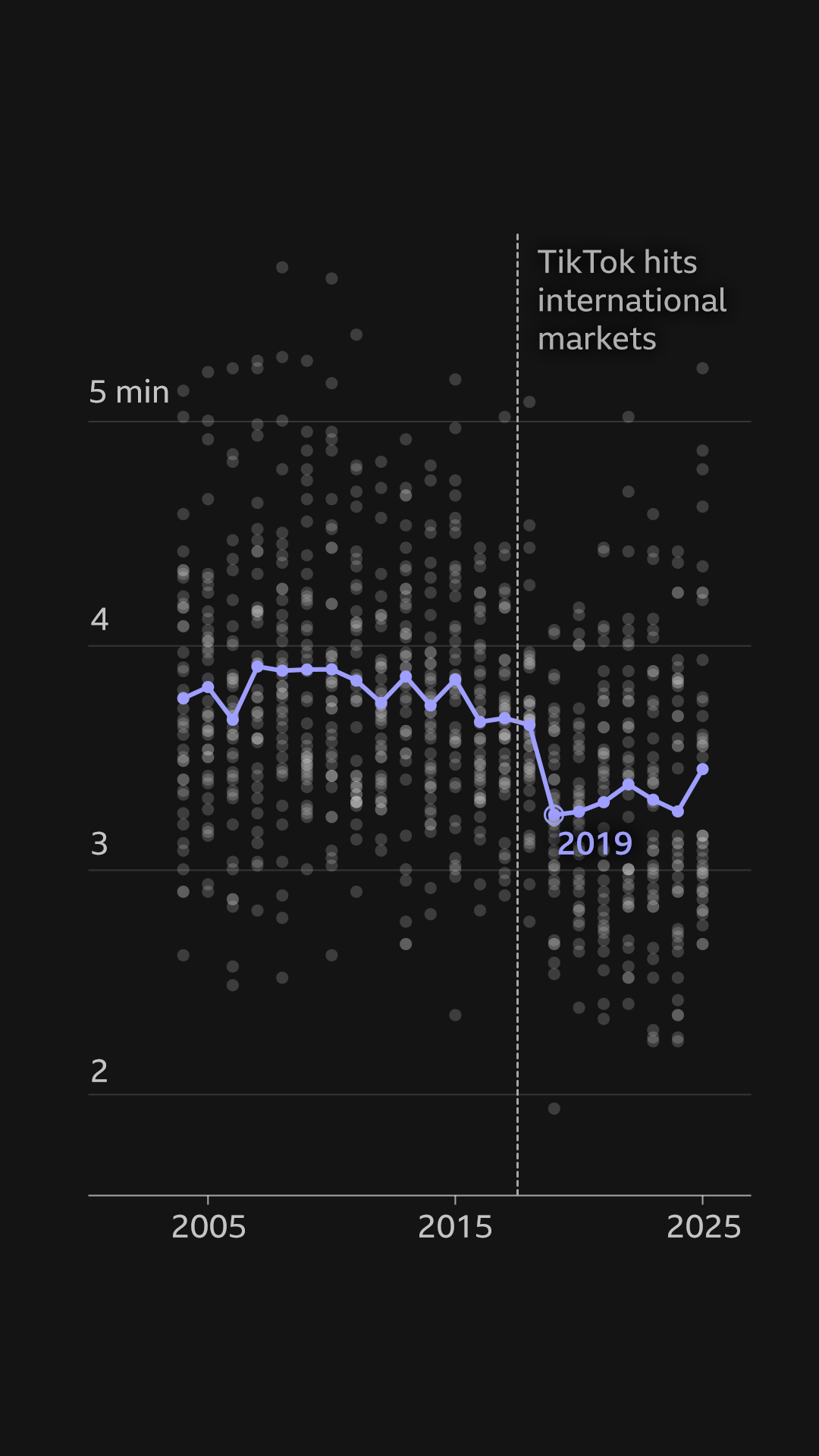

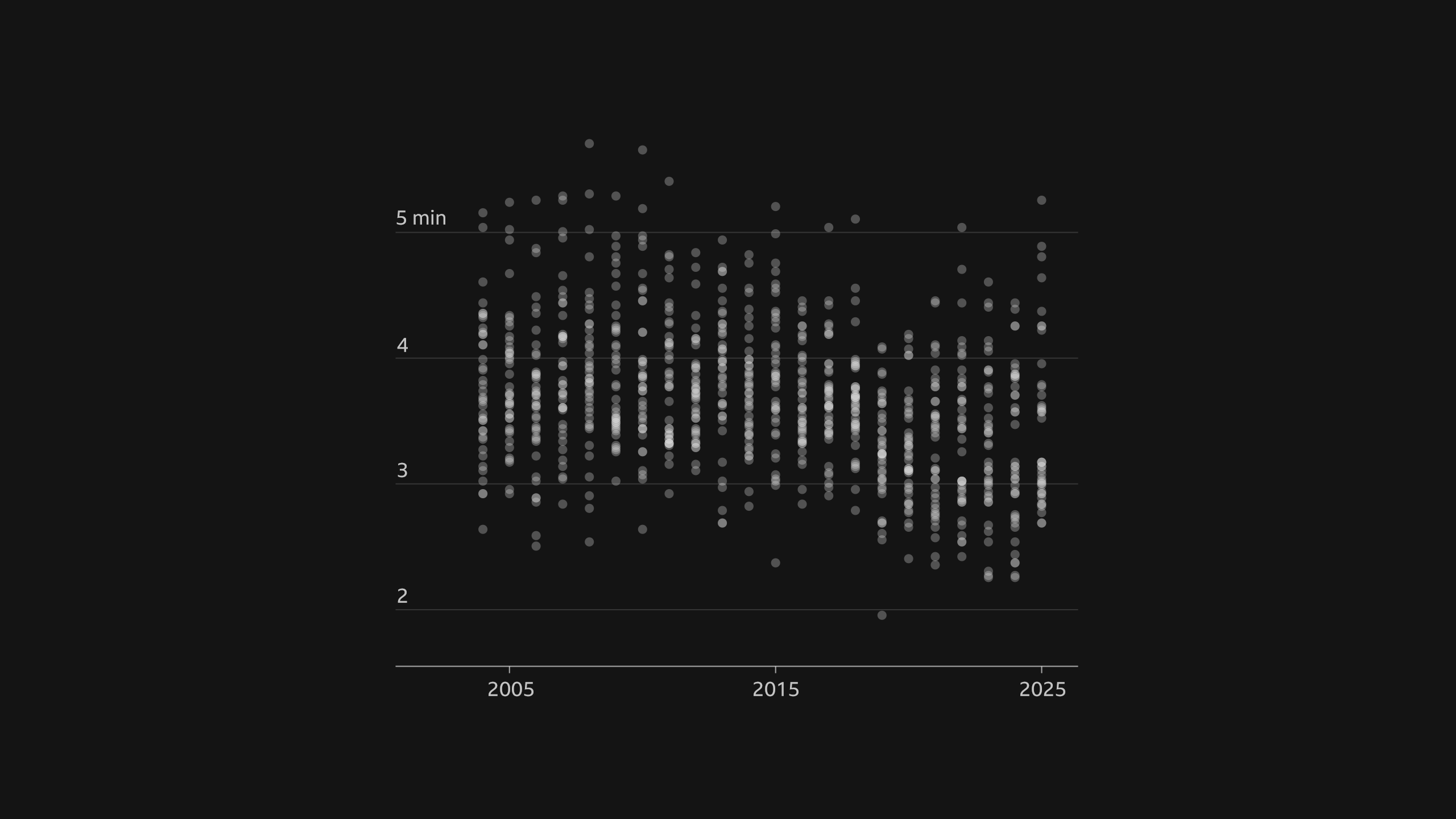

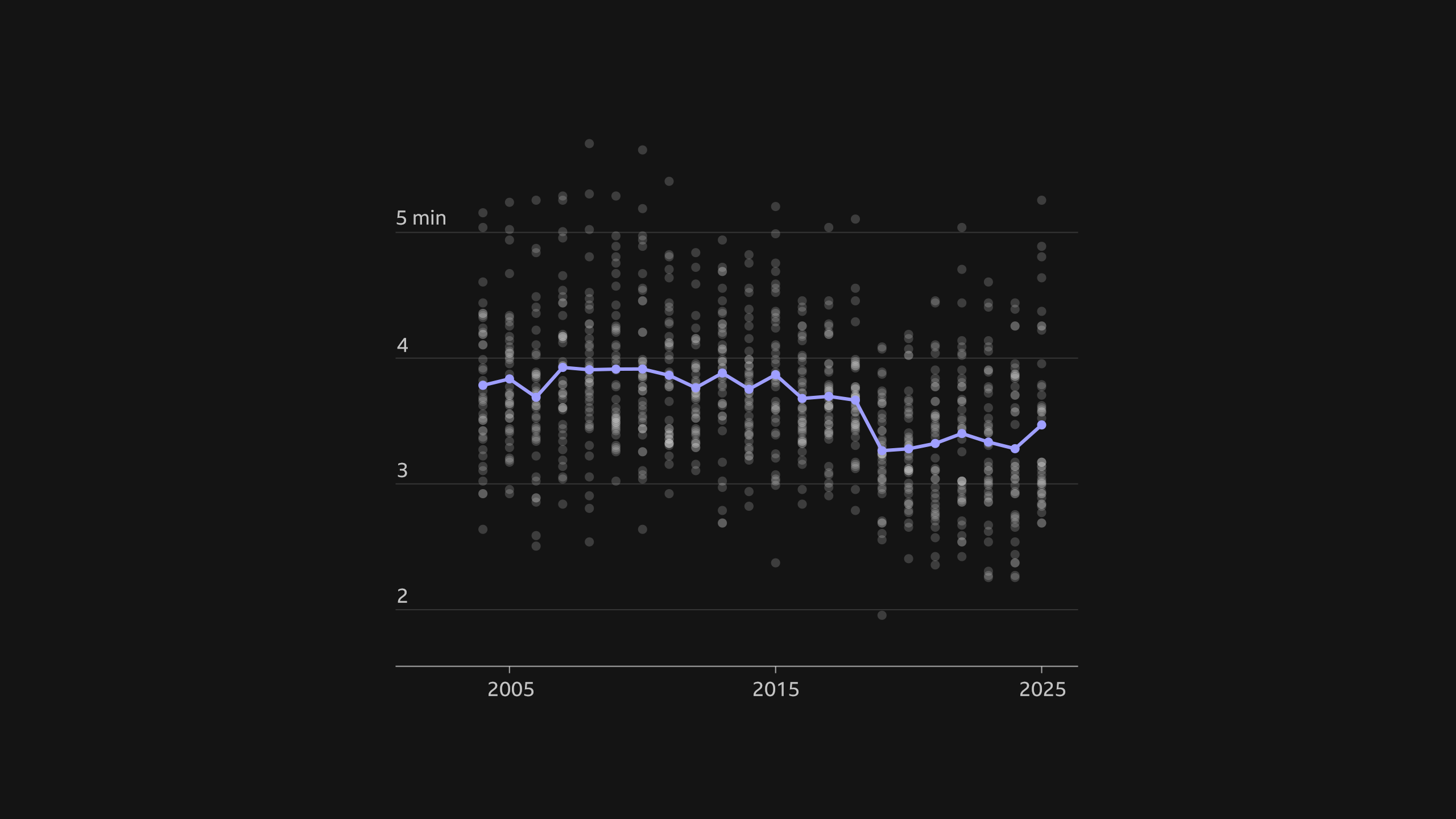

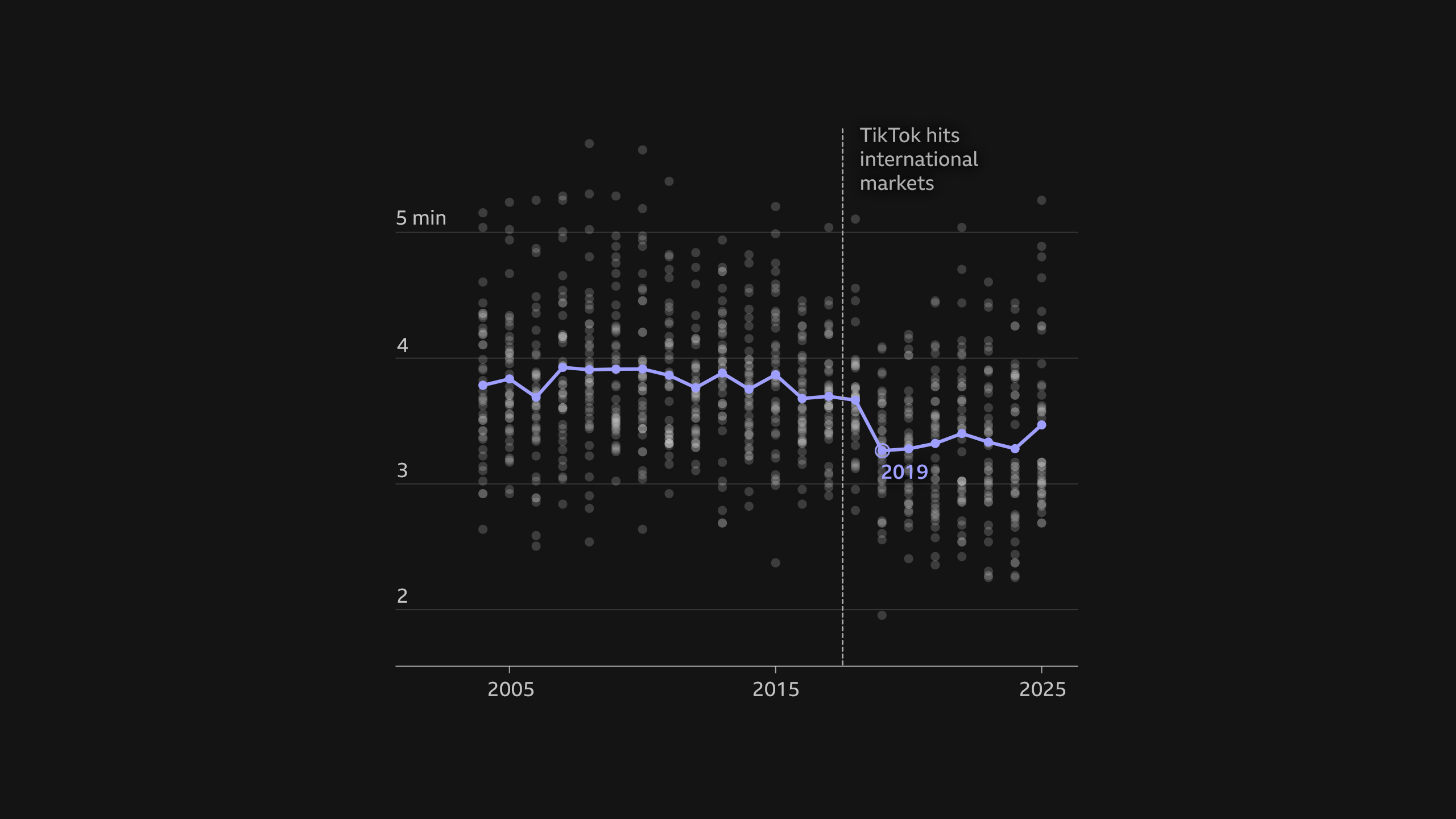

It's a fair answer, but the charts suggest otherwise.

Songs got drastically shorter in the streaming era. But new BBC research shows that trend is over...

"When TikTok came along, it changed a lot of things," says Ines Dunn, a songwriter with credits on hits like Mimi Webb’s House On Fire (2m 20s) and Maisie Peters’ Run (2m 49s).

"People’s attention span dropped quite dramatically. You tune in for 20 seconds of a song, you don't know the name of the artist, you don't know anything, really. You just love that bit of music."

But musicians soon discovered that there’s a reason why TikTok is named after the sound of a ticking clock.

"You had to get people’s attention in the first two seconds, and it only really mattered if the song had one line that did well," says Claudia Valentina, a British pop singer who’s just scored two global hits as a writer on Blackpink’s Jump (2m 44s) and Jennie’s Mantra (2m 16s).

"I remember being like, 'Why would I even finish the song? I might as well just make a 30 second thing that's a meme, so that it'll go viral'."

Valentina wasn’t the only person thinking like that.

In London, a film student called Victoria Walker started posting unfinished snippets of music to TikTok, using the app as a crowd-sourced quality filter.

If a track gained enough likes, she’d finish it and release it under her stage name, PinkPantheress.

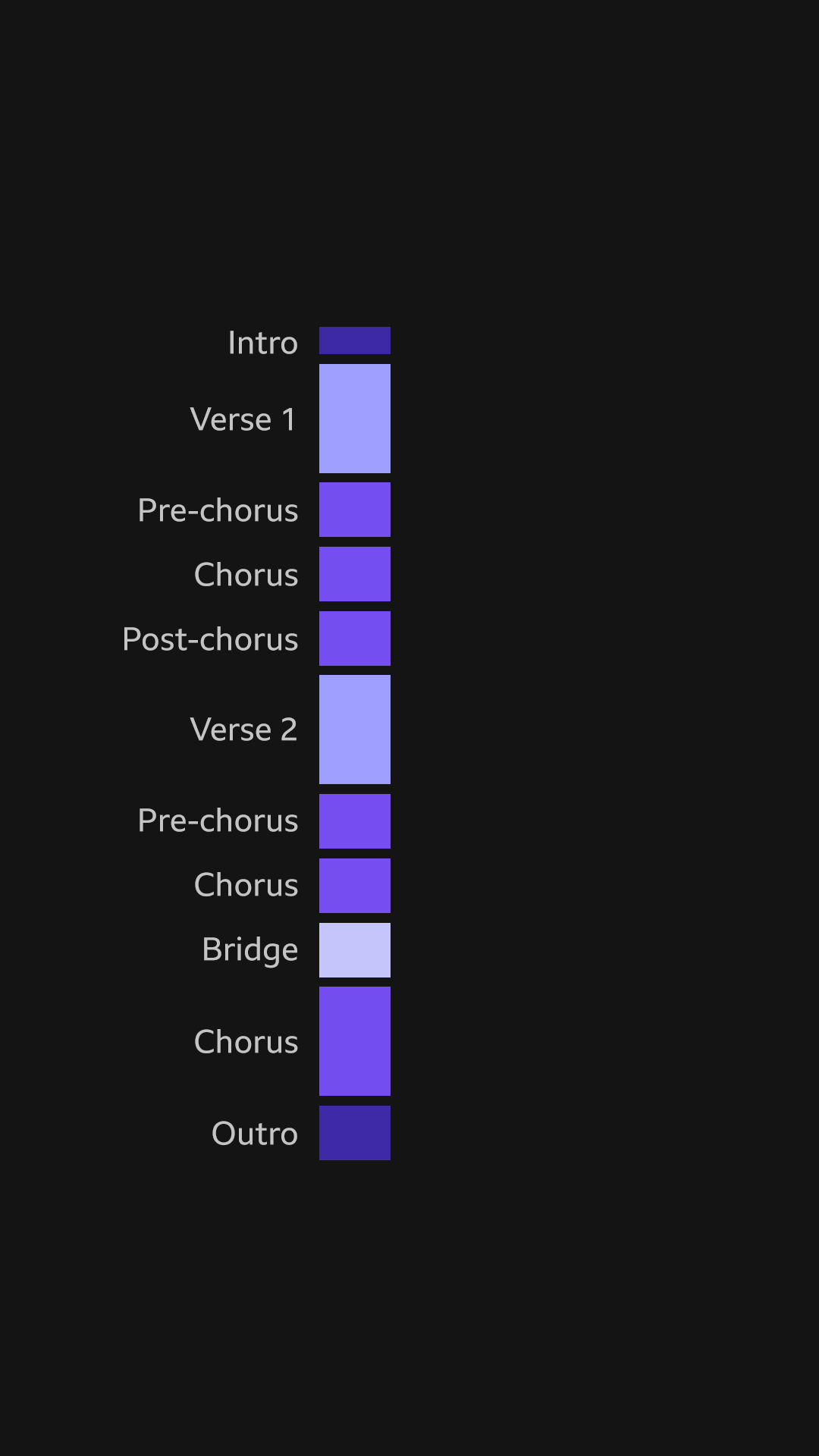

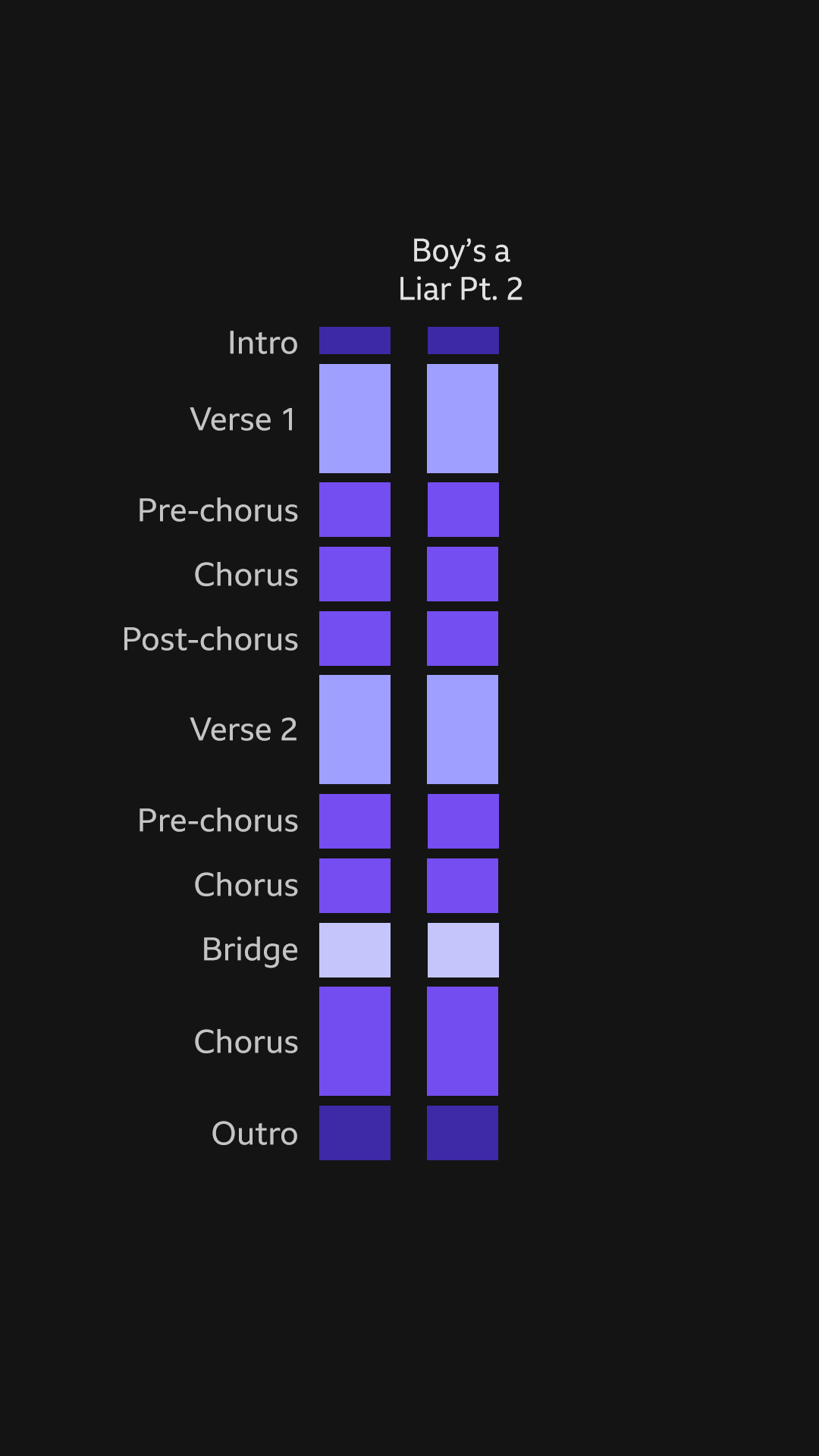

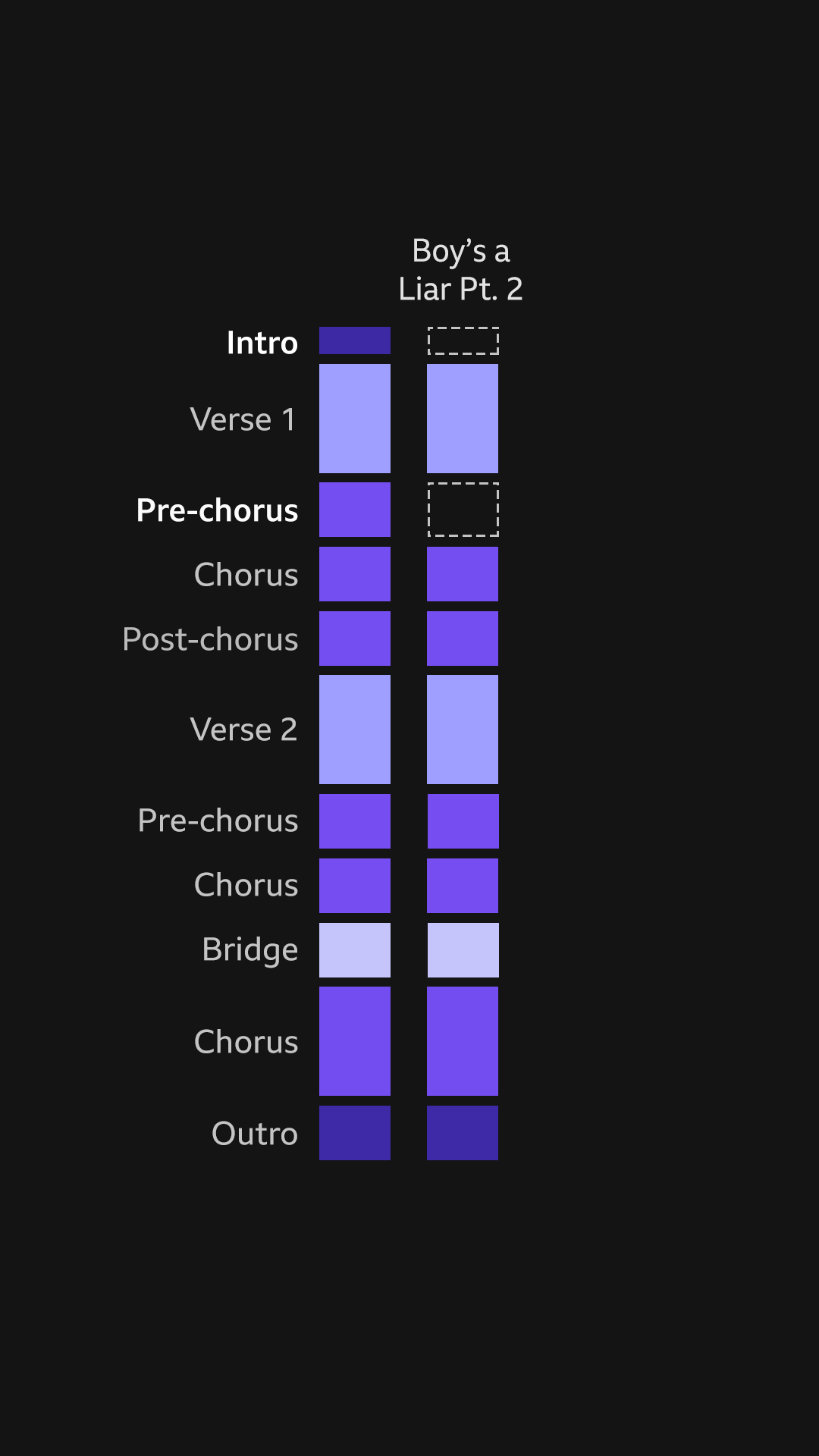

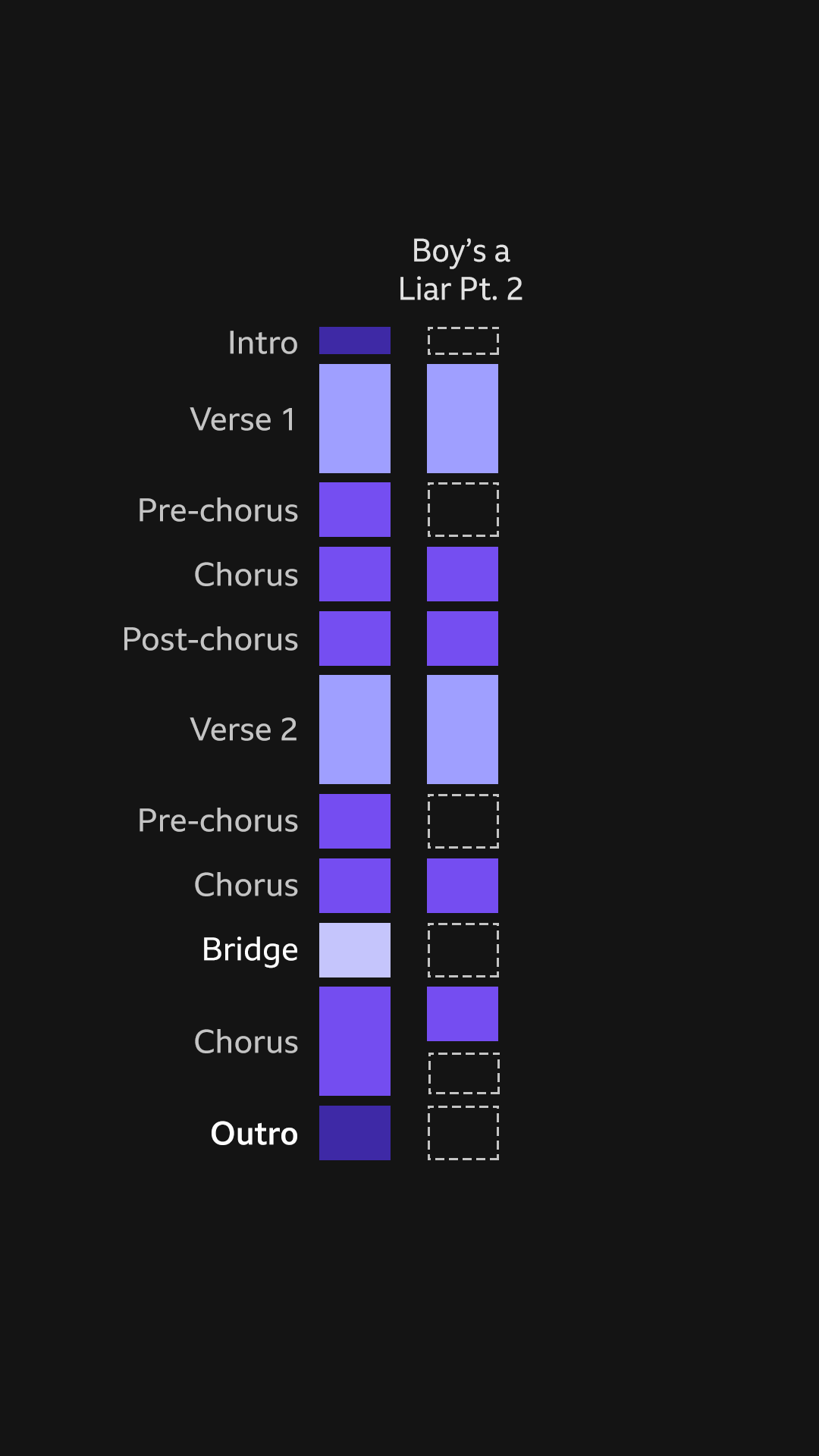

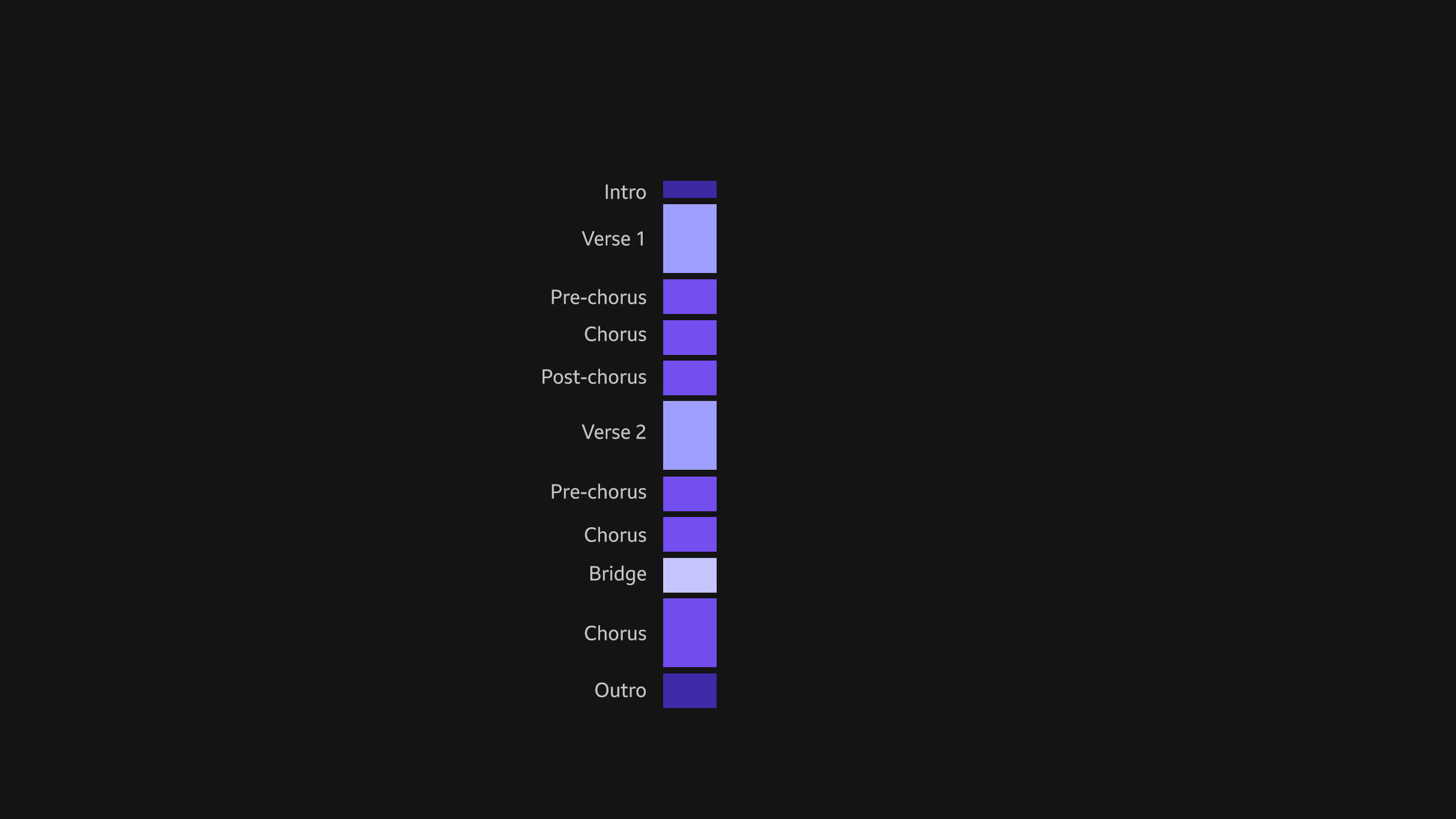

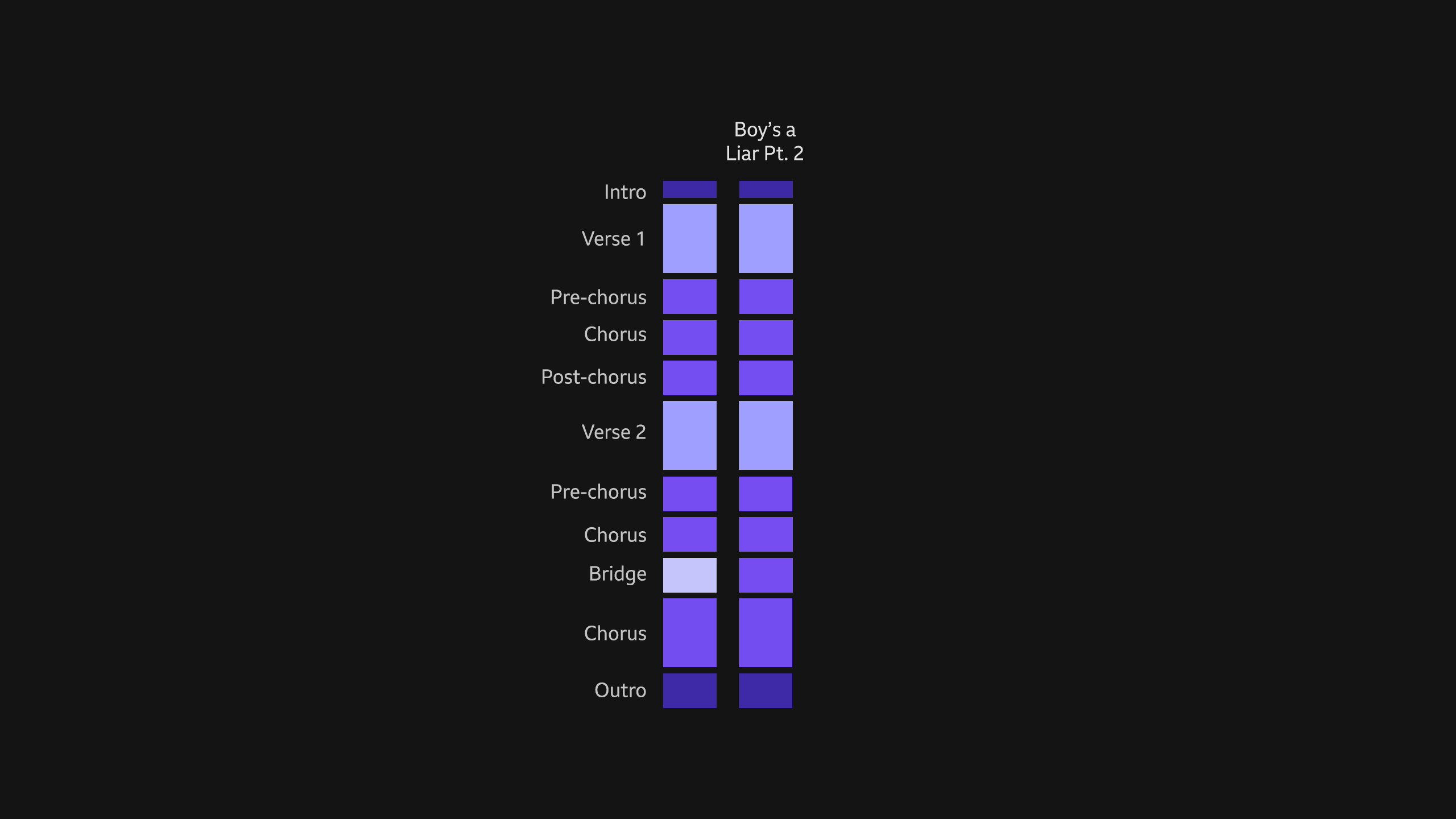

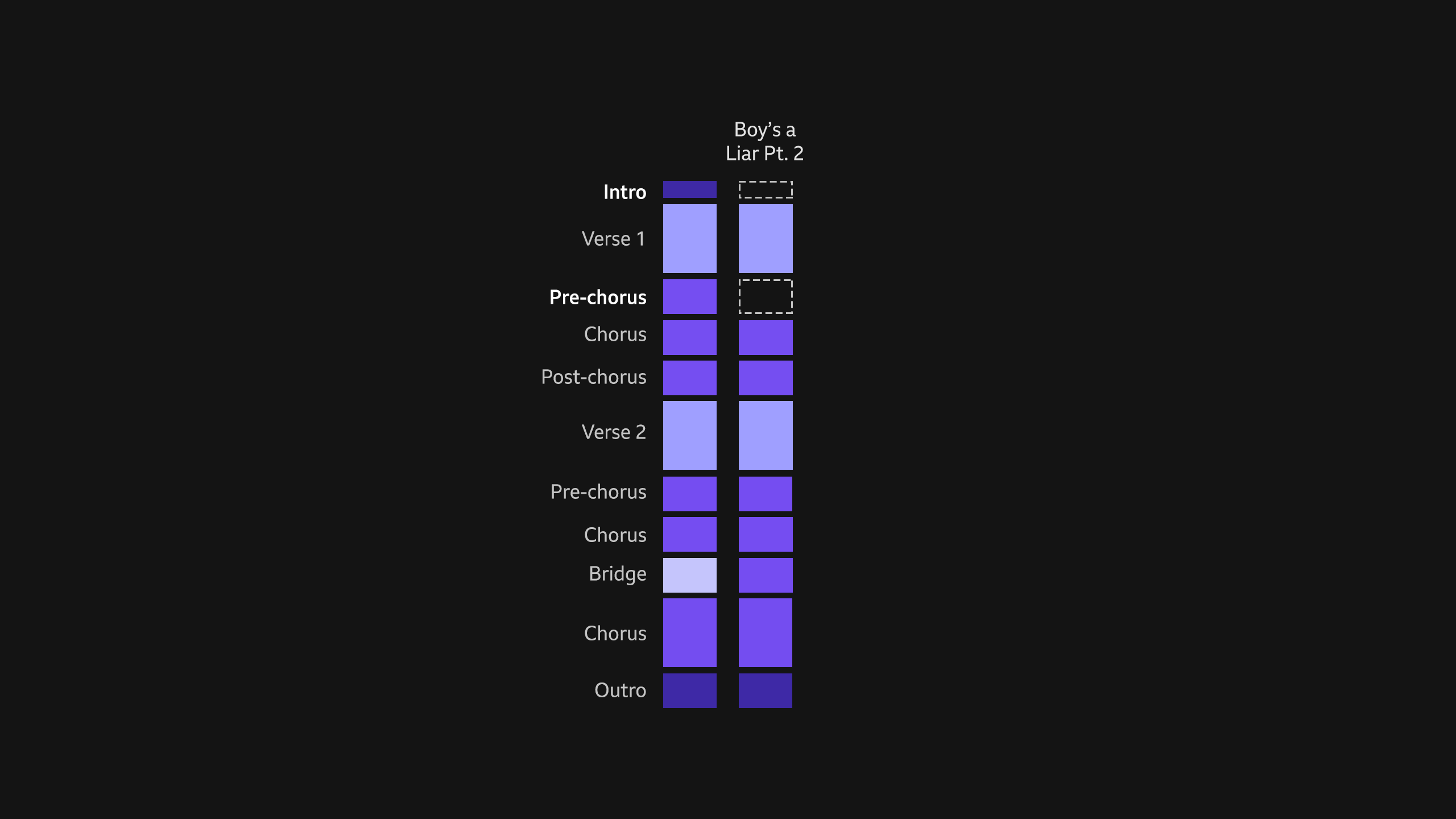

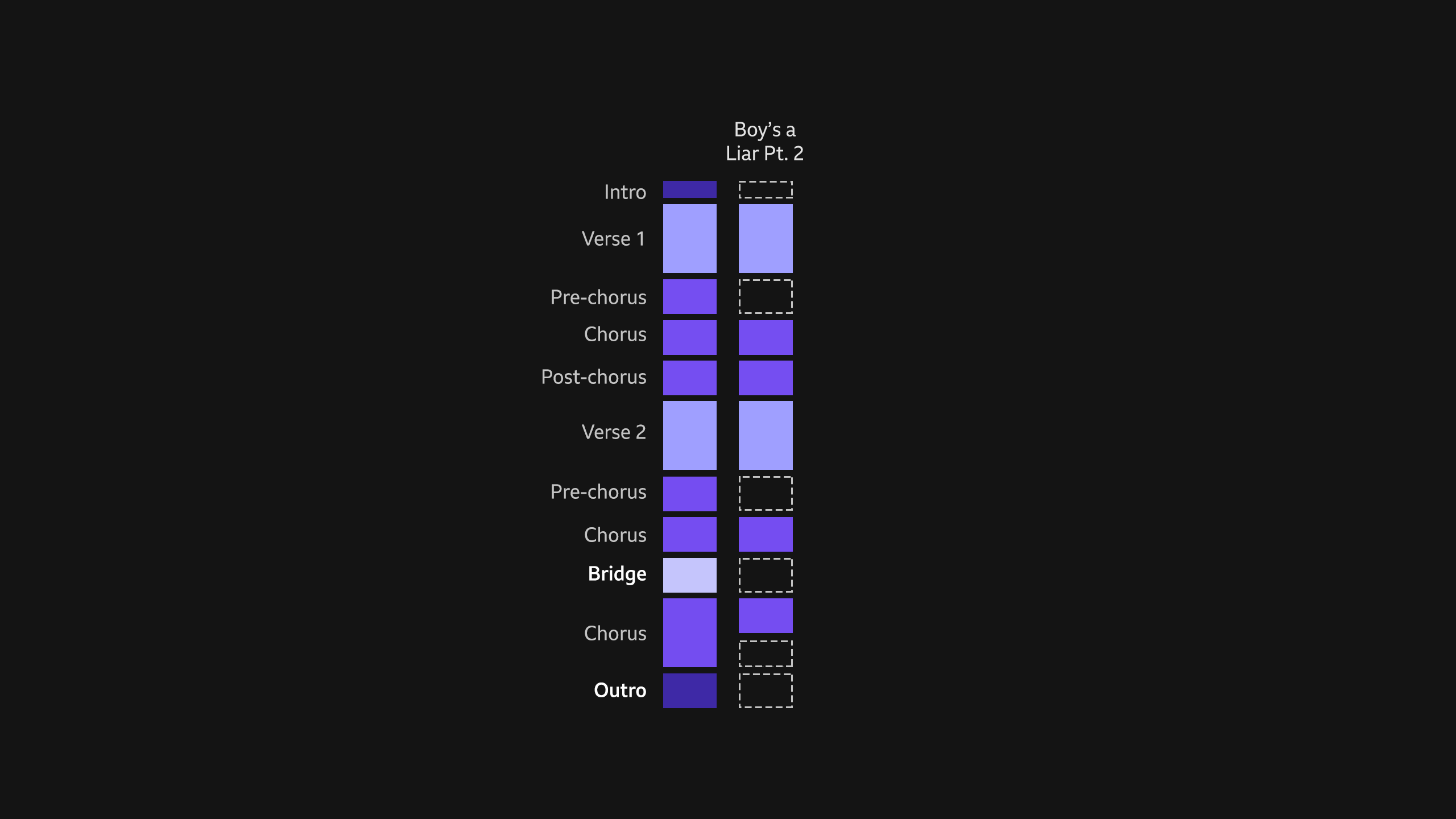

But even then, she found it pointless to stick to traditional song structures.

"I just get really tired of singing the same melody again and again," she told me in 2022 . "By the time I've finished one melody, I'm like, 'OK, I can do better,' so then I move on to another one and another one."

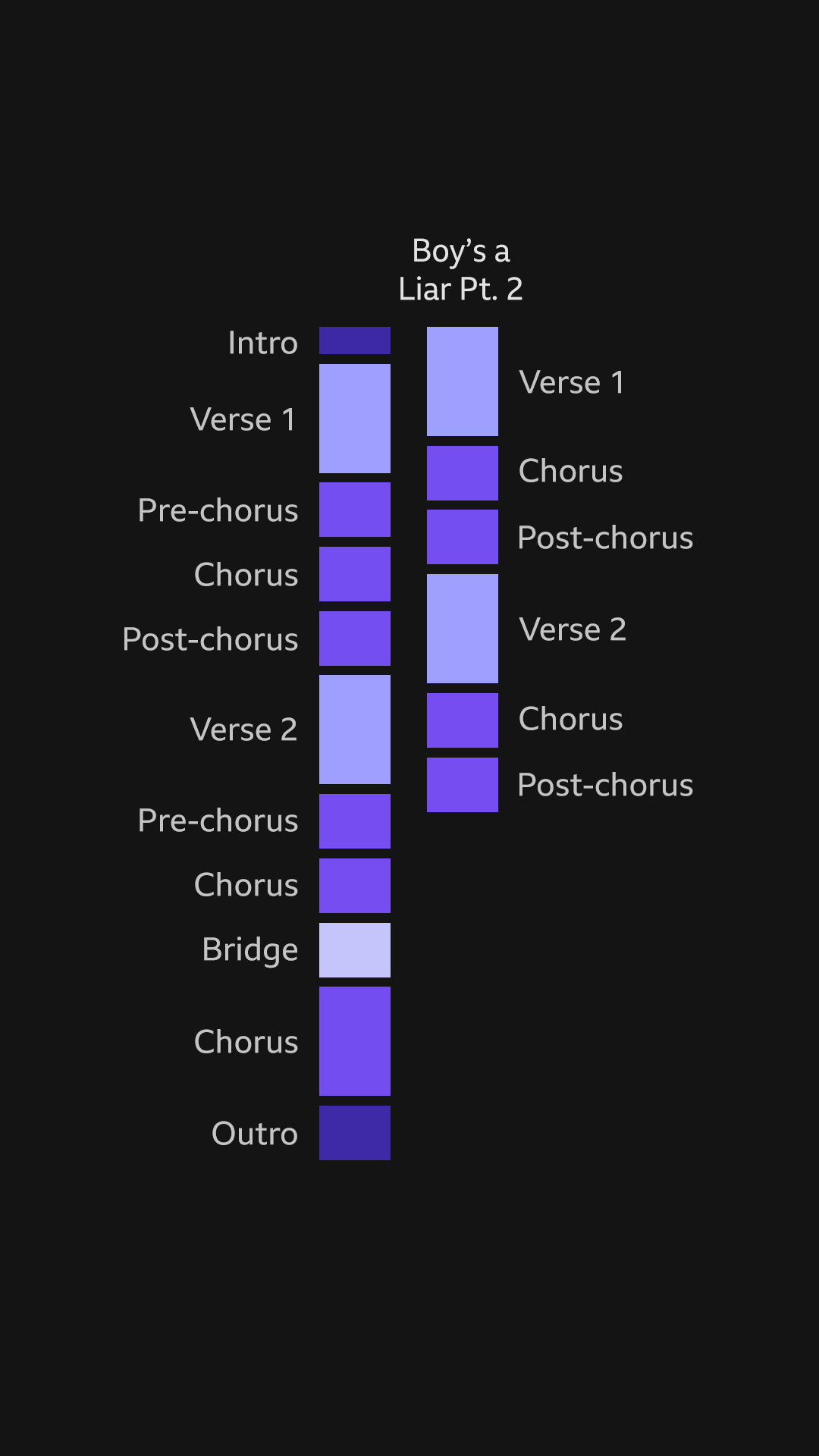

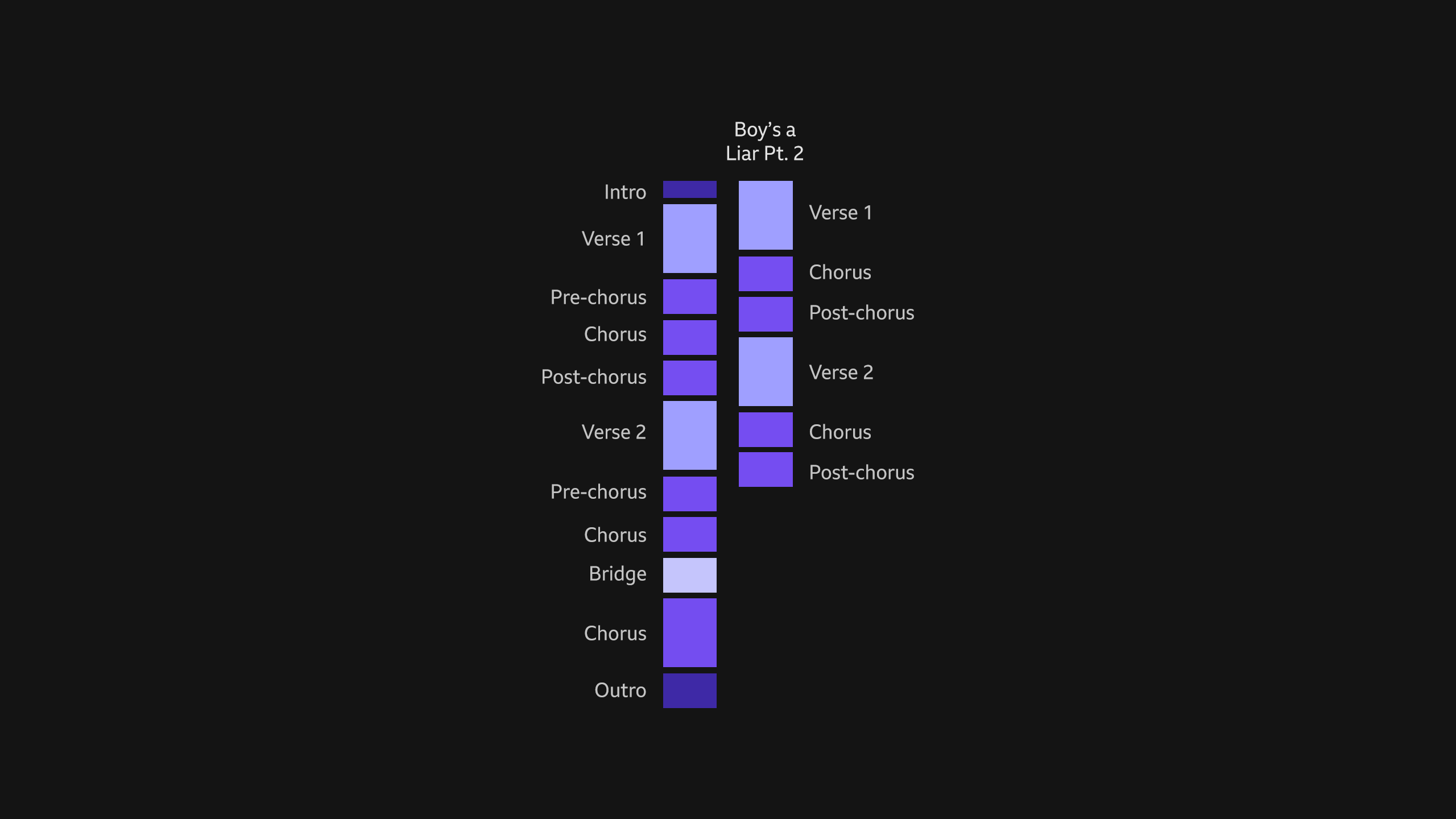

With hits like Attracted To You (1m 07s), I Must Apologise (1m 48s) and Boy’s a Liar Pt. 2 (2m 11s), PinkPantheress became emblematic of attention deficit pop.

"Every time I write a song, I think it's going to be three minutes - then I see the length and it's always, like, one minute," PinkPantheress told me.

"So it's not something I consciously do but it just ends up being the case. I don't think it necessarily is a bad thing."

Brevity hasn’t harmed PinkPantheress’s career. She’s racked up hundreds of millions of streams. And, because streaming royalties are calculated on a per-play basis, her nine-track album Fancy That will earn the same amount in its 20-minute running time as Michael Jackson’s Thriller makes over 42 minutes.

Still, her music is crammed full of ideas and hooks, a virtue that doesn’t extend to other hits from the TikTok era.

"You start to notice songs that basically have just one catchy bit they hammer over and over again," says music critic Todd Nathanson, best known for his acerbic YouTube alter-ego Todd In The Shadows, and the Song vs Song podcast.

"Like Artemas, I Like The Way You Kiss Me (2m 22s). That song basically has five seconds that you know off the top of your head, and you couldn’t sing the rest of it. You probably don’t even know if there are any other parts to it."

"It doesn't really scan as a song, in the way that it would in the 1960s. Motown would not make a song like that."

Nathanson also mentions Unholy by Sam Smith and Kim Petras (2m 36), which sandwiches two perfunctory verses between three repetitions of its tantalising, Middle Eastern chorus before coming to an abrupt stop.

"It feels especially weird for that song, because it’s so grandiose and operatic, but it’s gone in a flash," he says.

"But why put in effort if you don't need to?

"If shorter songs are catching on, why break yourself trying to come up with a good bridge? Studio time is expensive, and writing things is hard."

But here’s the thing: people are pushing back.

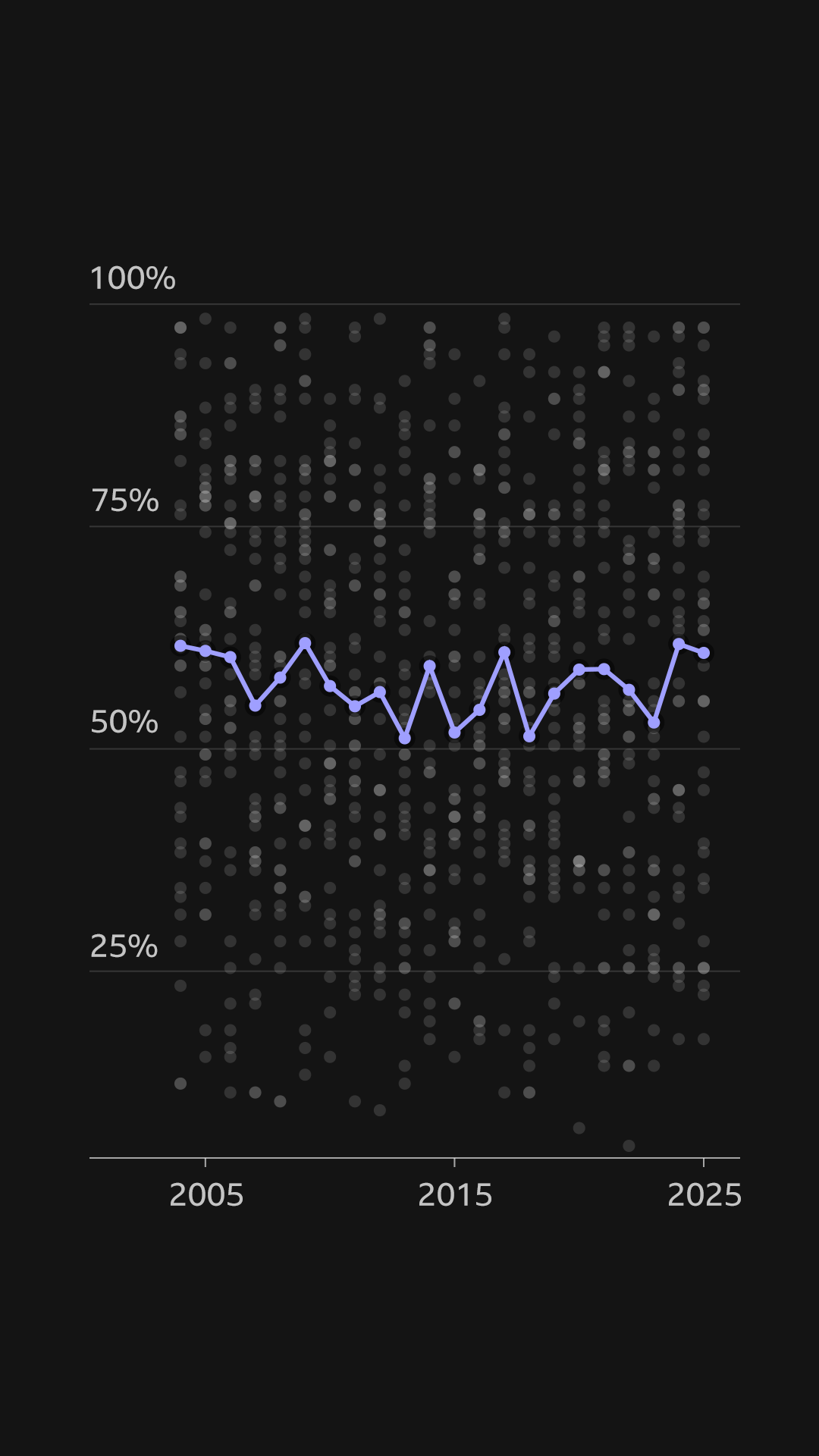

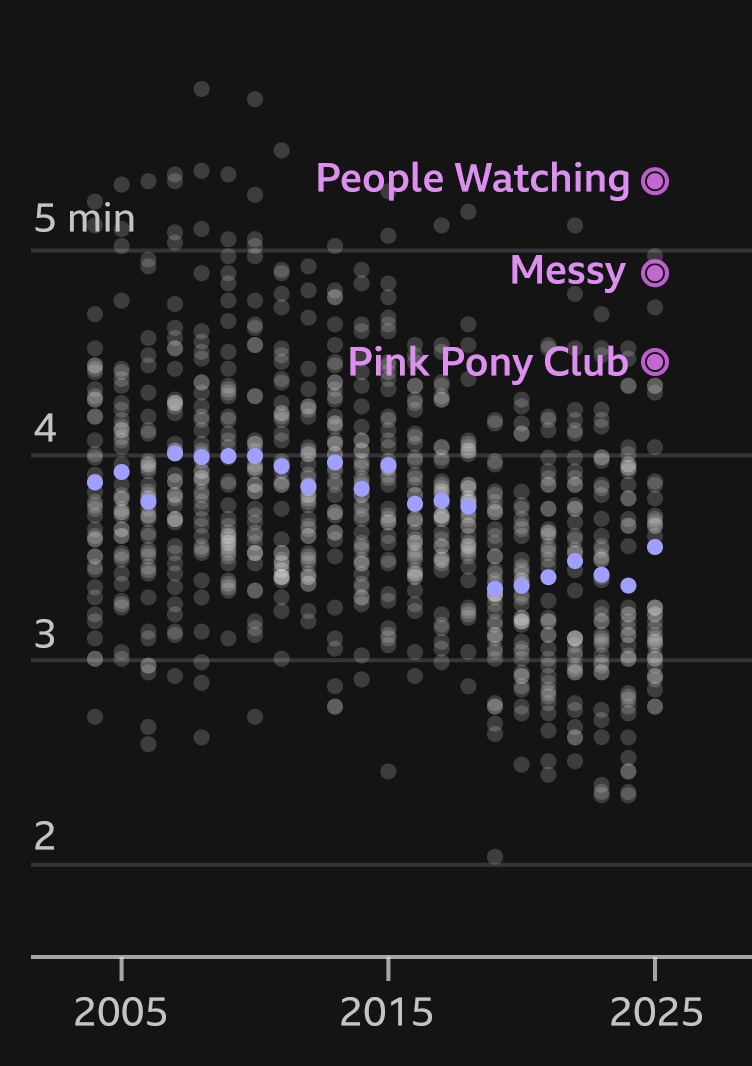

Chart analysis by BBC News shows that, since their nadir in 2019, song lengths have crept back up again.

The average length of a hit single in the first six months of 2025 rose to almost three and a half minutes. Some stretched out even longer.

The chart is now full of hits defying demands for diminution, like Lola Young’s Messy (4m 44s), Chappell Roan’s Pink Pony Club (4m18s) and Sam Fender’s People Watching (5m 11s).

It’s no coincidence that all three contain meaningful lyrics, with a distinctive worldview.

Lola Young’s anthem to self-doubt and internal conflict resonates with a wide audience, in the same way that Chappell Roan’s coming-of-age story gives a voice to thousands of closeted rural teens who hope to find themselves in the big city.

"I think fans have been thirsty to actually feel an artist’s presence in their work," says Valentina.

"Perspective is coming back," agrees Dunn. "Taste is coming back. People's uniqueness is making them successful."

In other words, if you’ve got something powerful to say, people don’t mind how long it takes.

Raye’s Genesis, released in 2024, is a frank and fragile exploration of her mental health, and runs out the clock at seven minutes.

Yungblud’s recent single, Hello Heaven Hello, is an epic, nine-minute song suite.

"We wanted to swim against the current, in terms of song length, because everything is so digitised and compartmentalised," he says.

It’s not just size that matters. Other artists are rejecting what New York Times critic Jon Caramanica disparagingly calls "Spotify-core": that slightly washed out, mid-tempo sound which isn’t quite pop and isn’t quite indie and incorporates elements of hip-hop but somehow just fades into the background.

Among them is former Little Mix star Jade Thirlwall, whose solo debut Angel of My Dreams (3m 17s) is a quirky and frenetic race through half a dozen different musical genres and vocal styles.

"It is quite a bonkers song,” she laughs. “I wasn't chasing a radio-friendly hit."

If you asked artificial intelligence to write a song like Angel Of My Dreams, she adds, "it would glitch. It would explode".

"You need real artists in the room, having these visions and changing the game and long may that continue."

After half a decade of chasing virality, pop is becoming wayward and reckless again - and it's getting happier too.

"I like to think of it as recession pop,” says Dunn. "Everyone’s just going dancing to counter the fact that the world is falling to shreds."

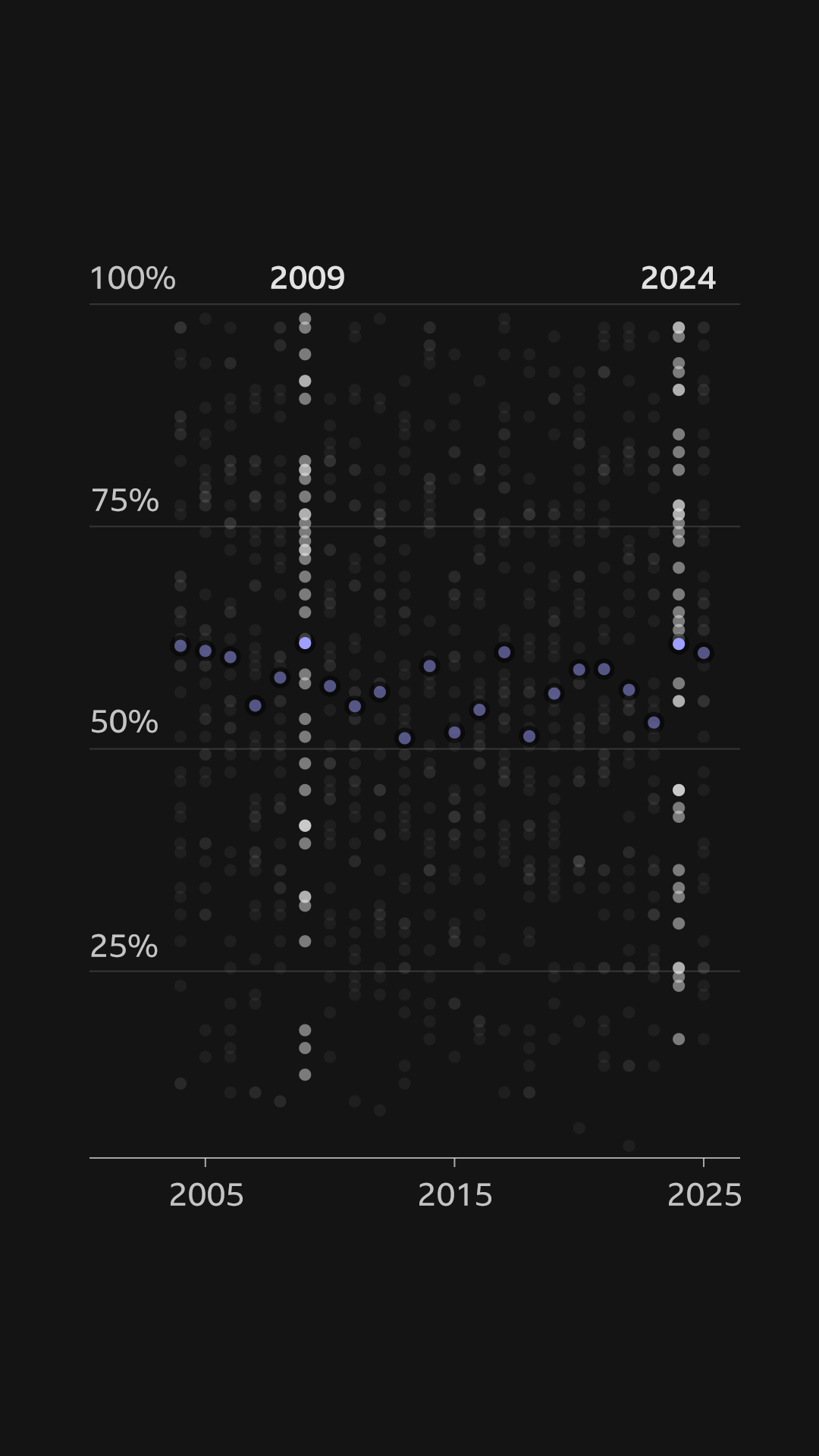

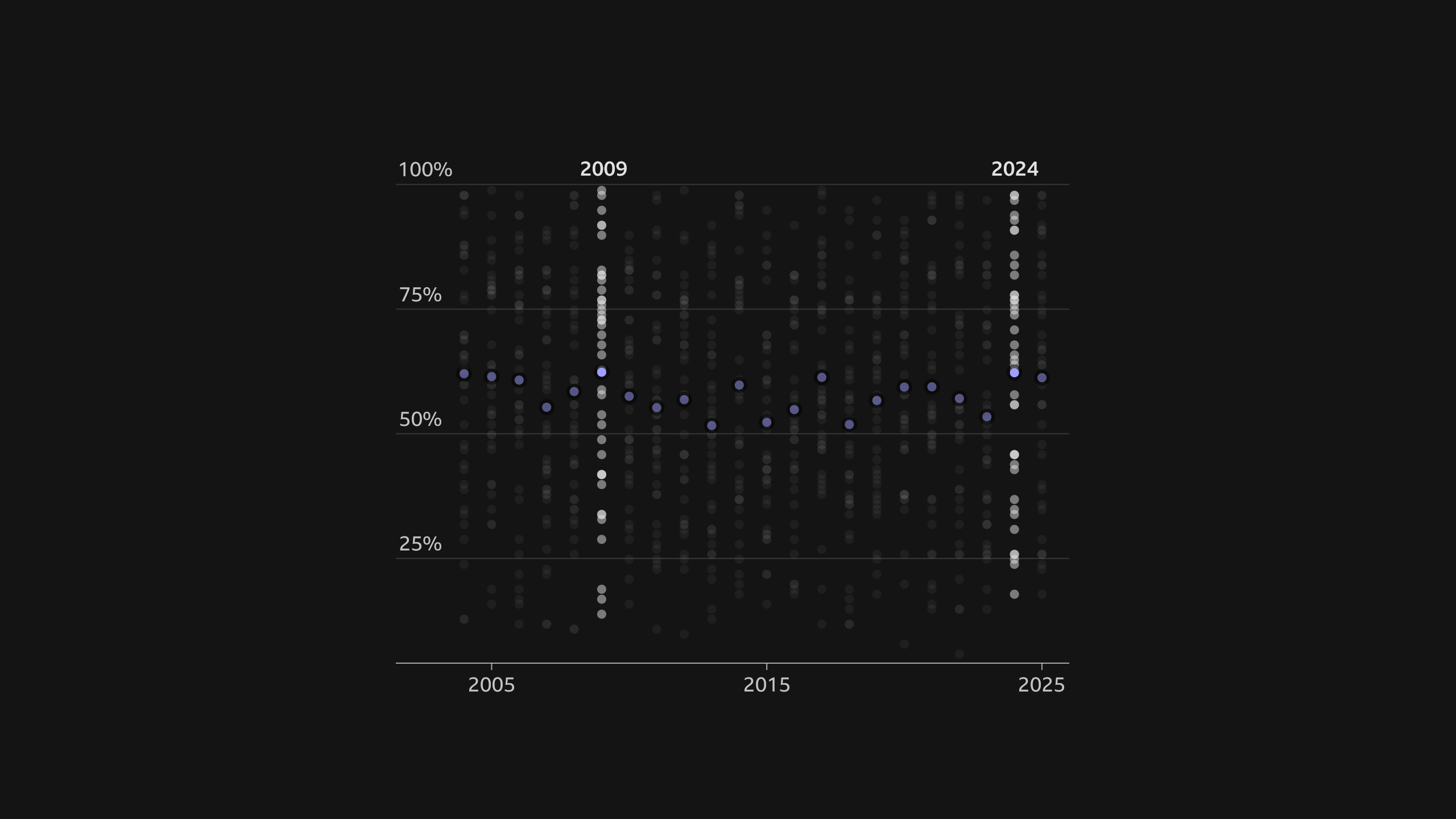

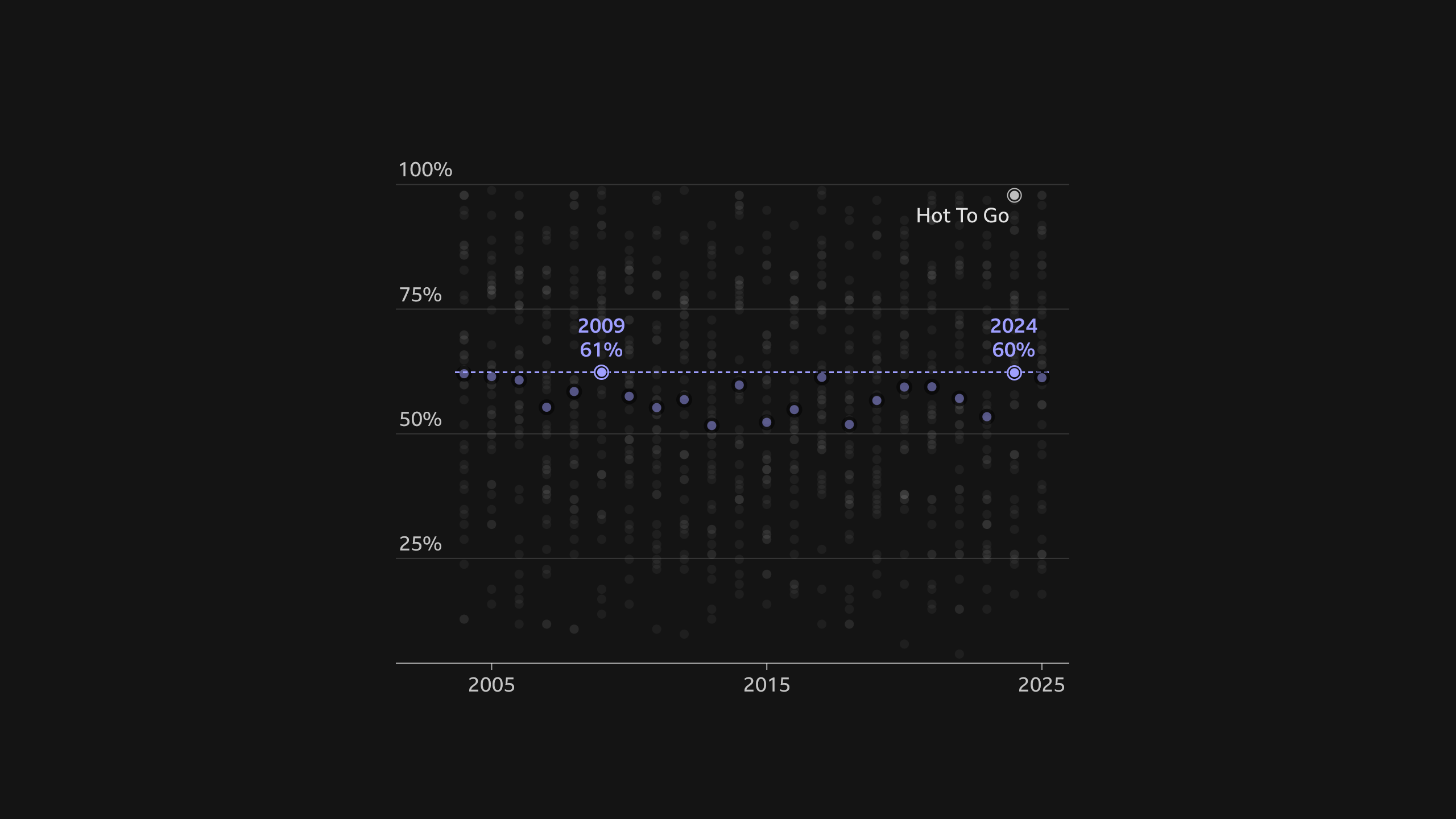

If you’re not familiar with the term "recession pop", here’s a brief explainer: In 2008, a global financial crisis, sparked by the collapse of the US housing market, was soundtracked by some of the most ridiculous, carefree music you could imagine.

As people tried to escape the grim realities of life, they turned to hits like Black Eyed Peas’ I Got A Feeling (4m 49s), Rihanna’s Only Girl In The World (3m 55s) and Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance (4m 54s).

So is it happening again? Luckily, we have the data.

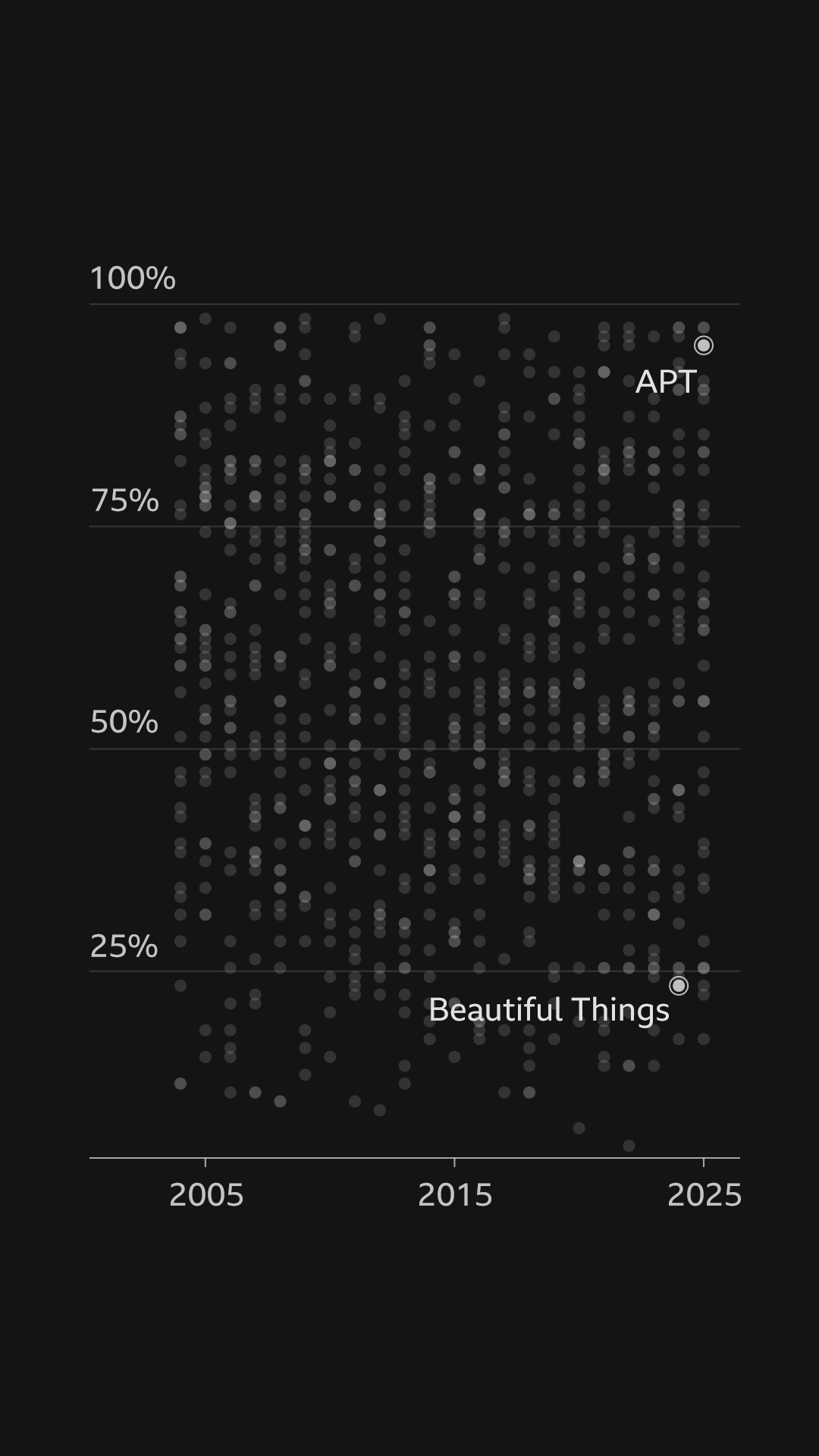

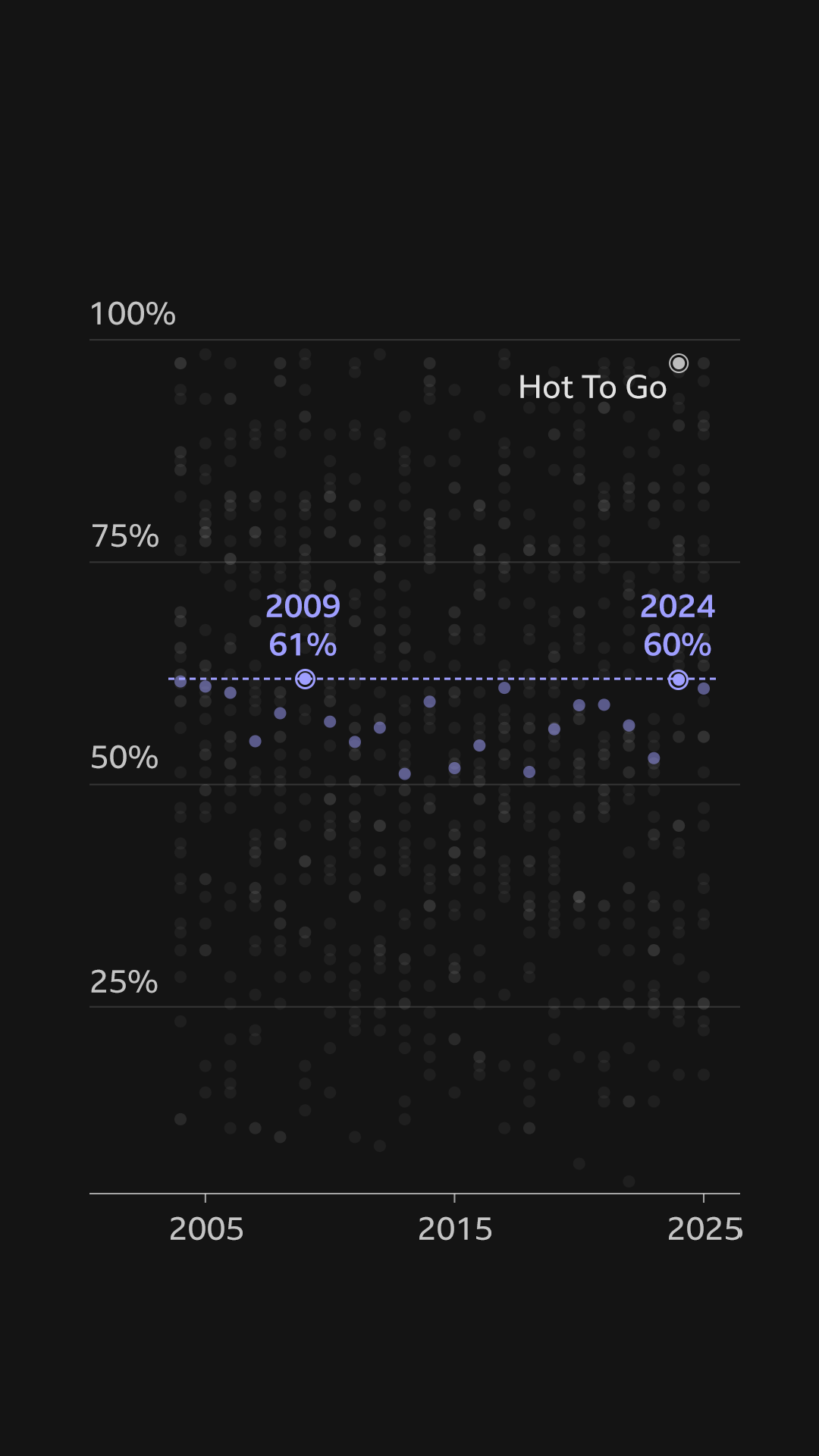

Five years ago, the BBC reported that the music people streamed during the Covid-19 pandemic was uniquely upbeat and sensual.

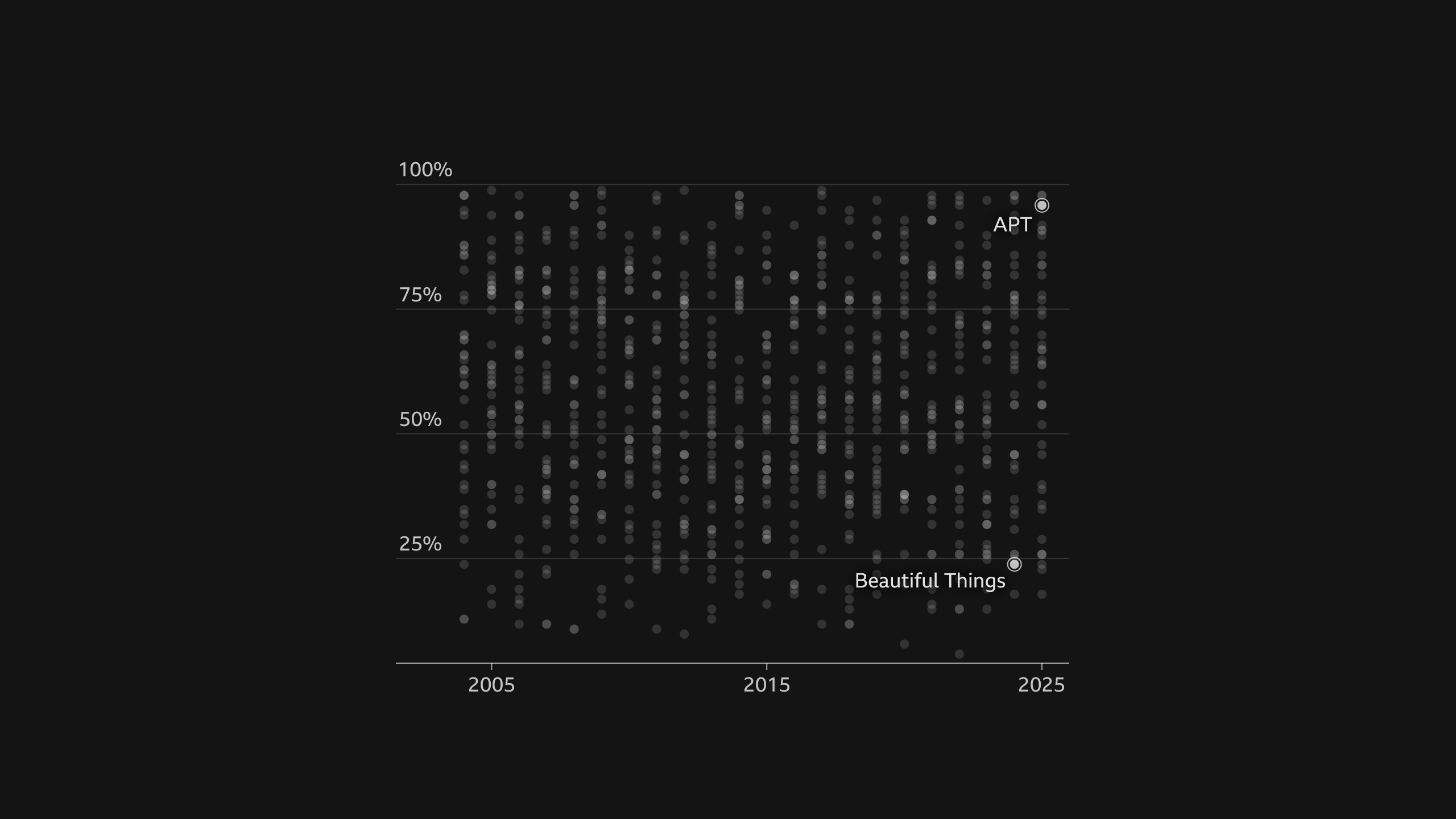

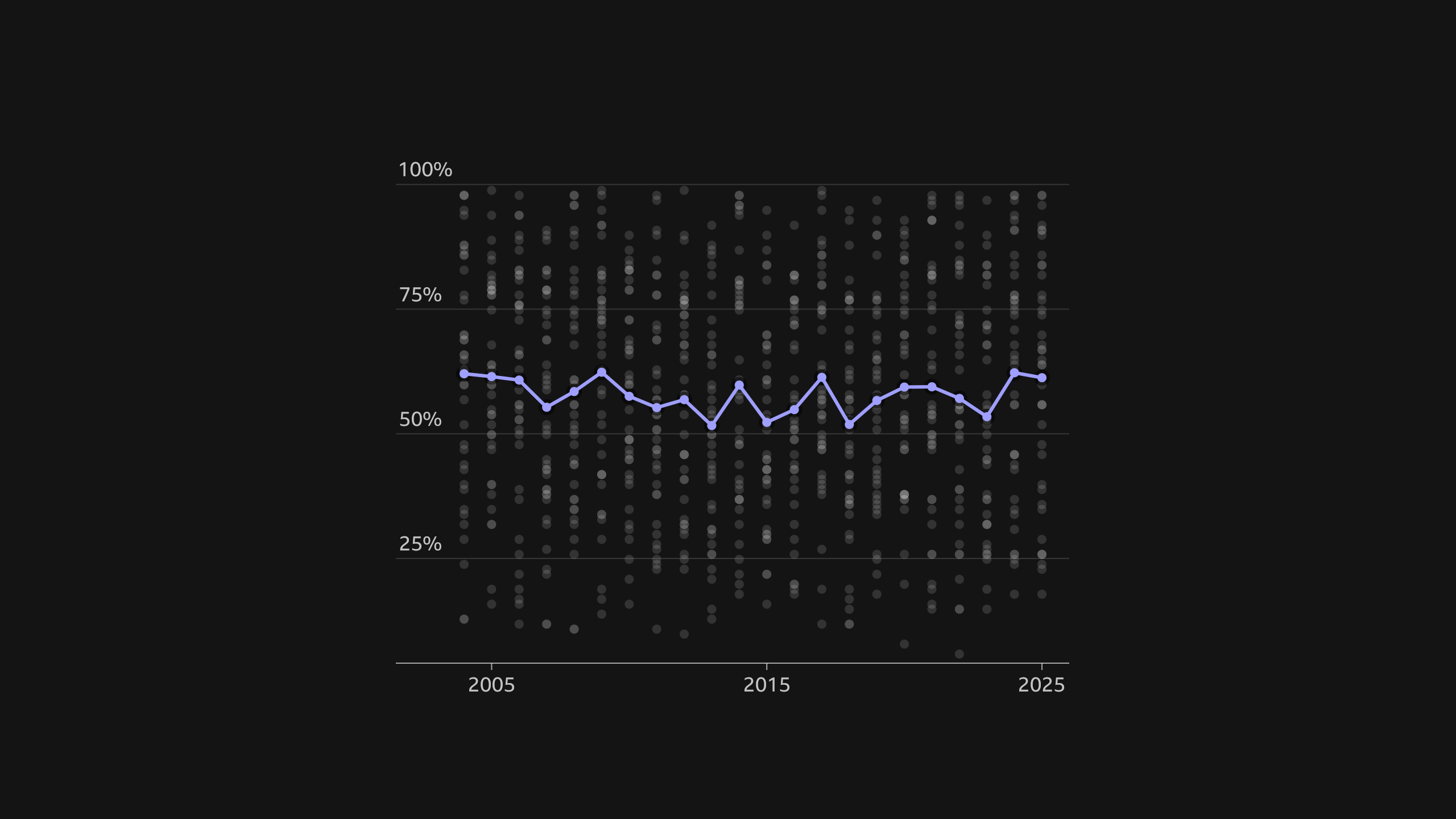

To illustrate that, we relied on the vast catalogue of musical metadata that Spotify generates for the 100 million songs in its database.

We were particularly interested in something called "emotional valence" - essentially a score for positivity, based on indicators such a song’s lyrical outlook, whether it is written in a major key, and the strength of its beat.

Tracks with a high score sound more positive (happy, euphoric), while tracks with a low score are considered negative (sad, angry).

It’s not a perfect measure, but it’s largely accurate.

But Nathanson cautions against mapping global events onto trends in pop music.

"No one calls disco, 'gas shortage pop'. No one says The Carpenters were 'Nixon's impeachment pop'."

Correlation, he says, is not causation. Music simply goes in cycles and, right now, the public wants happier, longer songs with a unique outlook.

Ines Dunn couldn't be happier.

"I don't know if we're going to get back up to Bohemian Rhapsody-length songs, but I think attention span is slowly creeping back up. And that means that people care, which is very much music to my ears.

"I'm like, 'Wow, I can make a three-minute song again!'"

Listen to a playlist of the songs featured in this article on Spotify, Apple Music or YouTube.

Additonal reporting:

Phil Leake and Becky Dale

Produced by:

Visual Journalism

Data:

Spotify via Musicstax, Genius