The science of a trustworthy face - and how to spot a liar (or Traitor)

“Nobody can spot a liar. At least if you do it’s through a slip - through reason, not this ‘gut instinct’ we put so much value on.”

So said Sir Stephen Fry, the Mensa card-carrier with a reported IQ of 170, shortly before he was voted out of The Celebrity Traitors.

Watching the show, his theory certainly seemed to prove itself to be true - it took a full seven episodes for the 16 so-called “Faithful” contestants in the gameshow to identify the first of the three lying “Traitors” in their midst.

Sir Stephen's theory is at odds with conventional wisdom, though. For centuries people really did believe they could read faces, an ancient practice known as physiognomy.

It was used in the 19th century to identify criminals - features apparently associated with “less civilised” humans, such as large jaws and cheek bones, asymmetrical features, prominent brow ridges or noses that were considered to be flat or big, meant you were at risk of being deemed dodgy.

Utter nonsense, of course: it was everything to do with social and racial prejudice and nothing at all to do with science. It has long been discredited.

Yet some modern studies suggest that we continue to be biased by the superficial, trusting people based on their perceived levels of attractiveness, their facial symmetry and their facial expressions.

All of this can, scientists argue, make a face appear more trustworthy to others - even if in reality, that person is as unscrupulous as Jonathan Ross, Alan Carr and Cat Burns put together.

The Halo effect

Among the evidence that we tend to put a lot of stock into superficial features is a study published in 2000, which suggested that attractive people are perceived more positively - in other words, as more intelligent, competent and reliable.

“What is beautiful is good. That’s the assumption,” Rachael Molitor, a chartered psychologist and lecturer at Coventry University says. "If you see someone and you find them attractive, you assign all of these positive qualities to them.” Although, of course, the notion of what is considered to be attractive or beautiful varies wildly across the globe, and indeed across the decades.

But another study published back in 2015, which explored perceptions of attractiveness and trustworthiness, found that as a face becomes more typical or average, it becomes more attractive and more trusted.

This suggests there may be a certain halo level of attractiveness that leads to high perceptions of trustworthiness. And if this “attractiveness” goes over a threshold, then people begin to be perceived as less trustworthy.

Our “trust reflexes” - automatic, unconscious responses toward others - may also be triggered by a face that appears happy and friendly.

This was demonstrated in a series of experiments back in 2008, led by academics at Princeton University, in which participants consistently rated faces with happy or smiling expressions as significantly more trustworthy than the same faces displaying angry, sad, or neutral (grumpy) expressions.

The participants were generally recruited from the local university community, typical for cognitive science studies at the time.

A 2015 study among French volunteers, also found that smiles rated as more genuine strongly predict judgments about trustworthiness, and even signal higher earning opportunities.

On the flipside, obscuring facial features with sunglasses, masks, or even having a fringe can diminish perceived trustworthiness, Dr Molitor says.

How trustworthy is my face?

So, in a potentially career-threatening move, I asked researchers about the trustworthiness of my own face.

They first investigated the symmetry in my facial features.

Symmetry equals beauty, which equates to trustworthiness, explains Mircea Zloteanu, a lecturer in psychology and criminology at King's College London. But again, there is a halo effect.

“A small degree of bilateral facial asymmetry is expected in all humans,” Dr Zloteanu says. “So, some facial symmetry can be related to beauty, but not too much symmetry or it starts to appear unnatural.”

This is also why too-perfectly symmetrical faces, such as digital avatars, robotic or artificially created faces, can seem almost creepy. (There’s even a term for the feeling it elicits - “uncanny valley”, a sense of unease or revulsion when encountering something that’s almost, but not quite, human.)

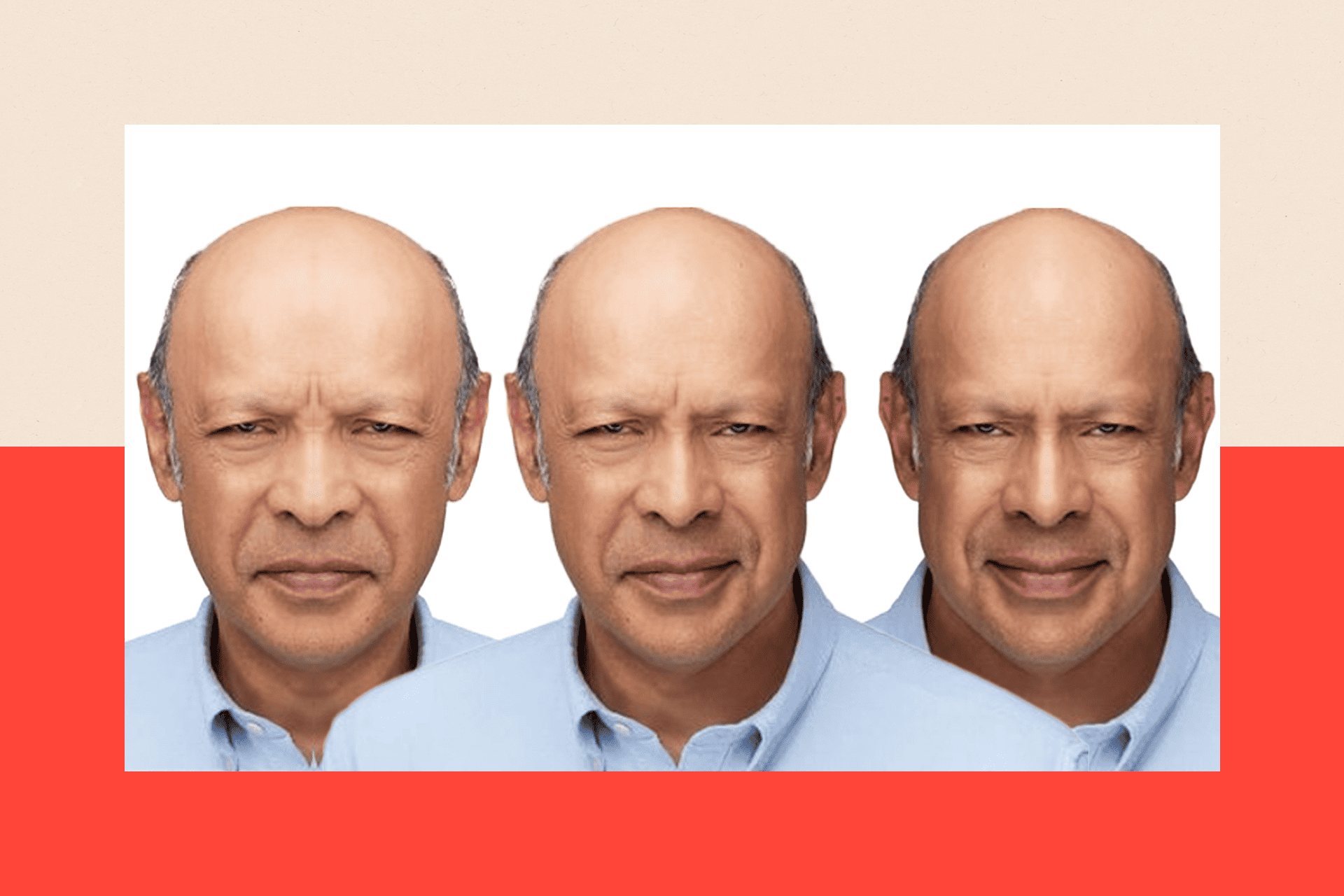

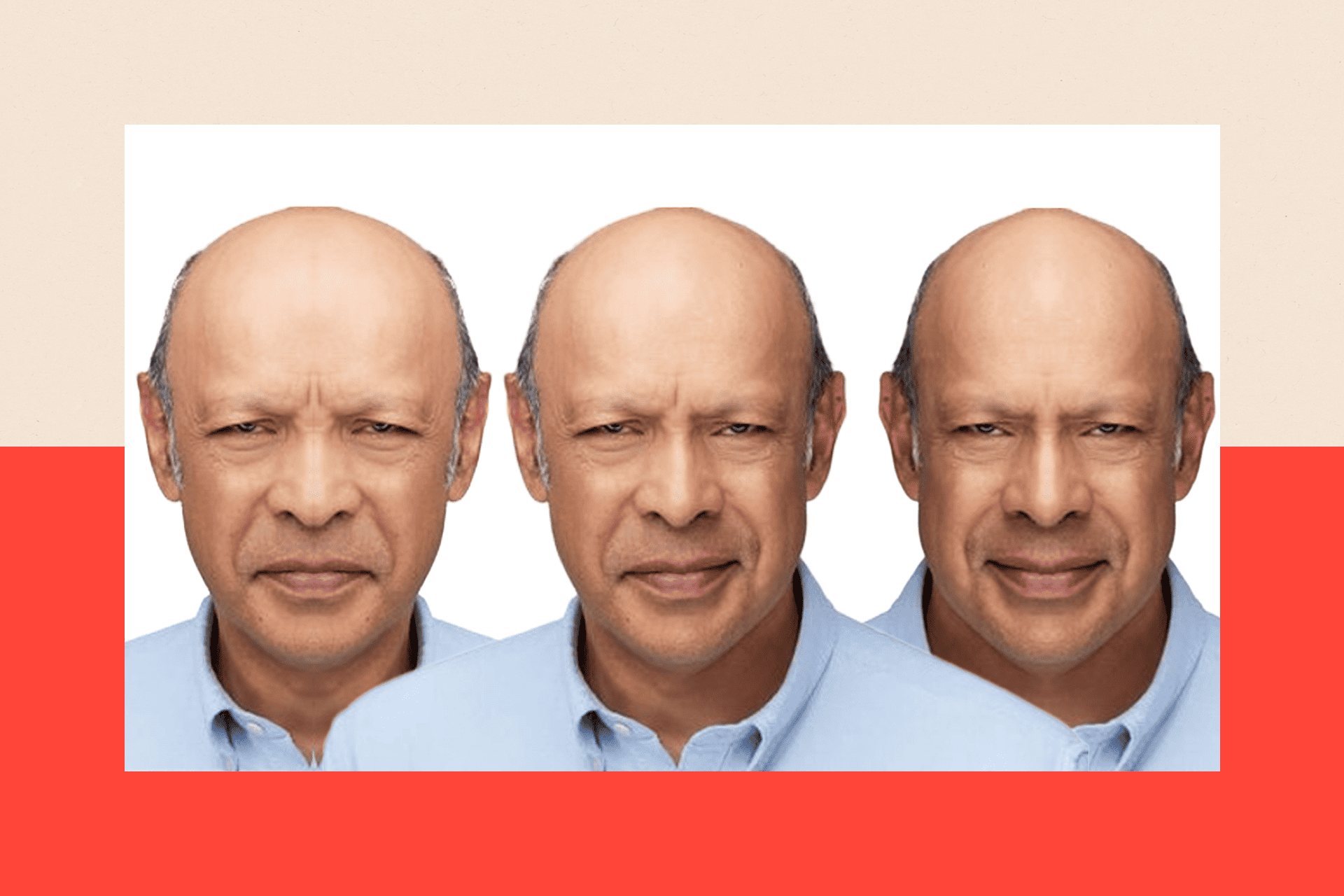

In an attempt to demonstrate how my face could become more trustworthy, various clever editing was done to it. Mila Mileva, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Plymouth, helped with this, manipulating the photograph of my face - the symmetry of my face was adjusted, and my lips tinkered with until they formed a smile.

Next she took this a step further. Some studies have shown that female voices, faces and names are perceived to be more trustworthy than males ones - other studies have also indicated that as the femininity of a face increases so does the perception of trustworthiness - so Dr Mileva rejuvenated my features to make them appear more feminine.

Afterwards, she gave the various versions of my face to 26 volunteers to score in a short online survey. The images were embedded within a set of 35 other images and rated for trustworthiness on a scale from one (not trustworthy at all) to nine (extremely trustworthy).

Though it was not an official scientific or academic review, the results were as expected - sure enough the younger, happier, feminine version is more trusted by the majority of the volunteers.

The verdict? I decide I can smile a little more if I want people to trust my science reports in future.

Herd mentality and false groupthink

But when it comes to the Traitors, questions around who to believe get much more complex and layered, on account of the group dynamic.

Dr Molitor specialises in deception. She is also a huge Traitors fan and has her own view on why it took this year’s contestants so long to identify a liar: she argues that groupthink, also known as conformity bias, results in poor decision-making.

"Herd mentality draws [people] into collective error, even when the evidence for betrayal is thin or ambiguous.”

She also says that the mind disregards evidence that does not support the original, often false, groupthink assumption.

The speed at which people tend to form impressions of how trustworthy someone is can also be part of the problem - and lead to misreading a person’s trustworthiness.

Dr Mileva explains that our ability to gauge trust evolved very early in human evolution - our ancestors needed to tell whether someone was a friend or foe in a split-second. “It is an extremely quick process. It takes us about a 10th of a second to form a very stable impression of trustworthiness,” she says.

The bad news is that her research shows that although our trust reflexes are quick, they are also terrible.

Why we’re terrible at spotting liars

Mircea Zloteanu, an expert in scientific approaches to lie detection and the social role of deception, agrees.

He has discovered two things. First, we think we are really good at spotting those we can trust and those who lie. And second, we're not.

“We all think that we’re able to spot a lie because we look for signs like sweating, looking away, blushing, fidgeting, or other bodily cues. But the truth is, these cues are incredibly context-dependent and not reliable indicators of deception at all,” he says.

"Someone could be sweating or looking away simply because they’re nervous, shy, or anxious - not because they’re lying. Often, we misinterpret these signals because we expect them to mean dishonesty, when in reality, they’re just signs of discomfort or emotional arousal in a particular situation."

In a series of experiments, volunteers watched videos or listened to conversations with participants who were either lying or telling the truth. The observers used typical cues, like sweating, looking away, or blushing, to try to spot the lies.

Dr Zloteanu and his team found that the volunteers couldn't tell the difference, and they were no better at spotting different types of lies, such as faked emotions or made-up stories.

Accuracy decreased even further when more people were involved, with groupthink, again, confirming an incorrect answer. Two or more heads were definitely not better than one, in this experiment.

Confidence didn’t help either; people who were sure they were right actually weren't.

"When you look at the scientific literature, and also when you look at our own results, which mirror [it], what you find is that people detect lies at a rate that is no better than chance,” Dr Zloteanu, told me damningly.

"So, it’s essentially equivalent to flipping a coin."

The mastery of the Traitors

Perhaps much of this accounts for why the Traitors got away with it for so long in this series.

The experts have their own views on how individual characteristics of the contestants played a part too.

So, is the lesson of The Celebrity Traitors simply that we will continue to be fooled by people we trust?

Dr Zloteanu argues that if it is, that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Scientifically speaking, he says, lying has had a bad rap for too long and in fact, the ability to be fooled and fool others has more socially useful benefits, than harmful ones.

"You lie to your friends about mundane things, you tell them they look good, that everything is going to be fine, that they don't have to worry about eating that second slice of cake.

“All of these things are not morally reprehensible. They are about building relationships, keeping the cohesion and helping others feel better.”

It is, in these sorts of cases at least, a type of “social glue”.

As for whether someone is being truthful, the critical insight for contestants on Traitors and the rest of us, say the scientists, is to become aware of these biases, to question first impressions, and - where possible - to pay less attention to our gut instinct.

So in that respect at least, national treasure Sir Stephen Fry was right.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published - click here to find out how.

Image credits

BBC/Studio Lambert/Cody Burridge/Matt Burlem/Artwork - BBC Creative/Euan Cherry/Mila Mileva