Arturo Suárez says he was beaten by guards as soon as he arrived at El Salvador’s notorious Cecot prison. When he regained consciousness - his glasses smashed - everything was blurred, he says, but he heard the greeting clearly.

"Welcome to hell. Welcome to the cemetery of living men. The only way you leave here is dead."

Arturo says the person speaking was the jail’s director, Belarmino García.

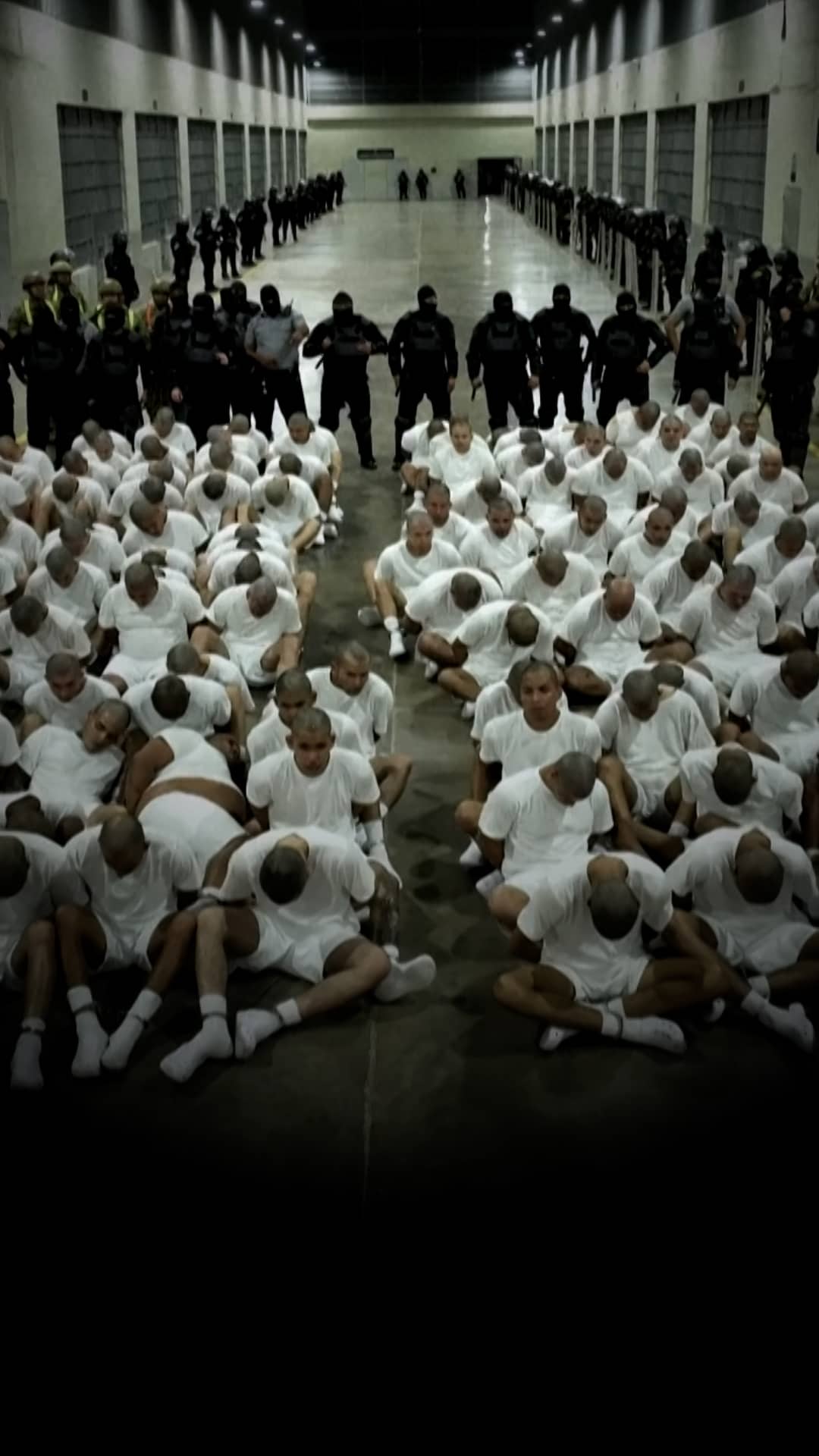

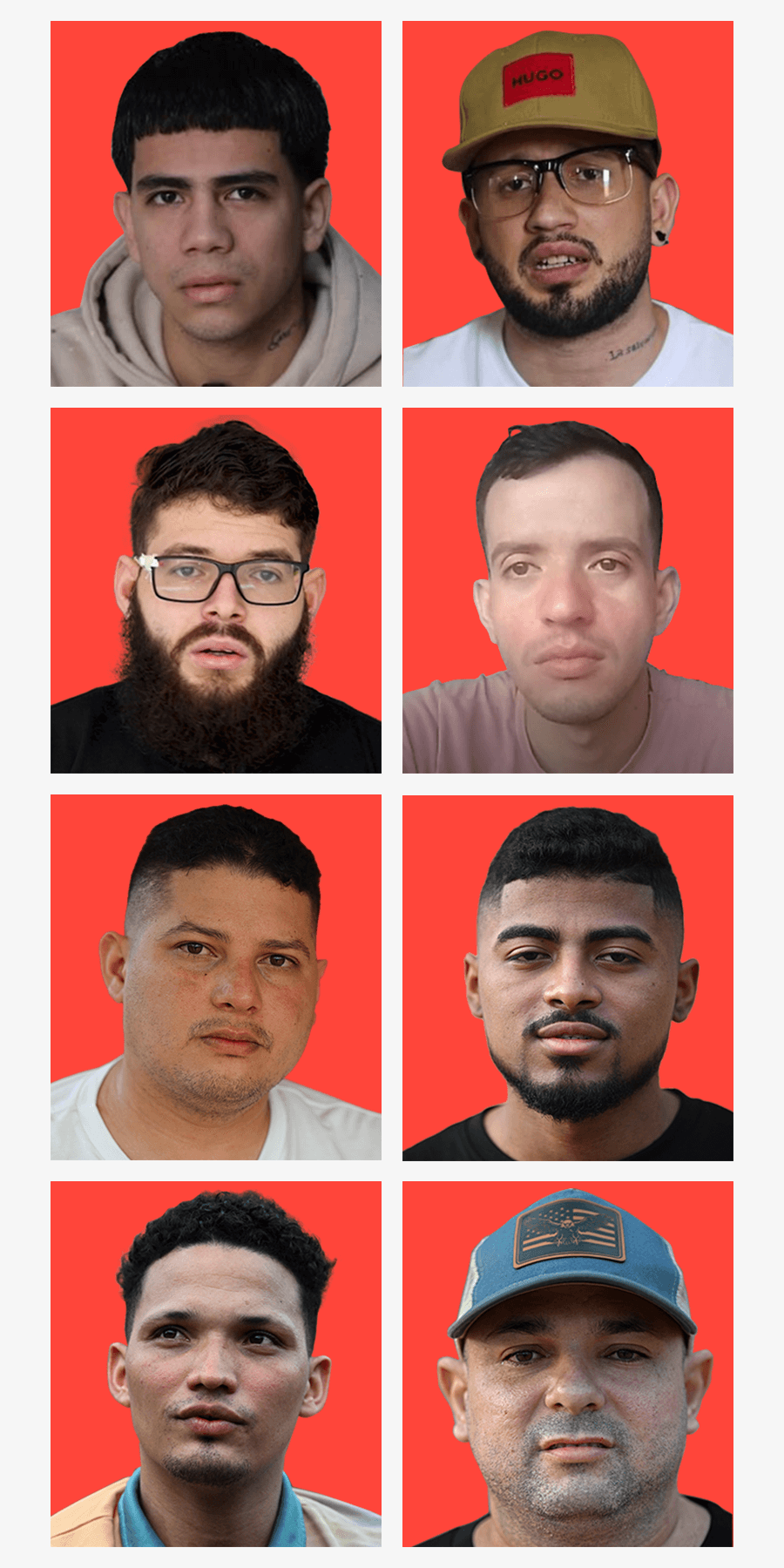

Cecot - the Center for the Confinement of Terrorism - was designed for the mass incarceration of El Salvador’s most violent and dangerous gang members, a symbol of President Nayib Bukele's hardline approach to the wave of murders and extortion that had terrorised the country.

Since it was opened in 2023, authorities have been secretive about life inside Latin America’s largest prison. And with few inmates ever let out, there has been little information available about what goes on behind its concrete walls and electrified fences.

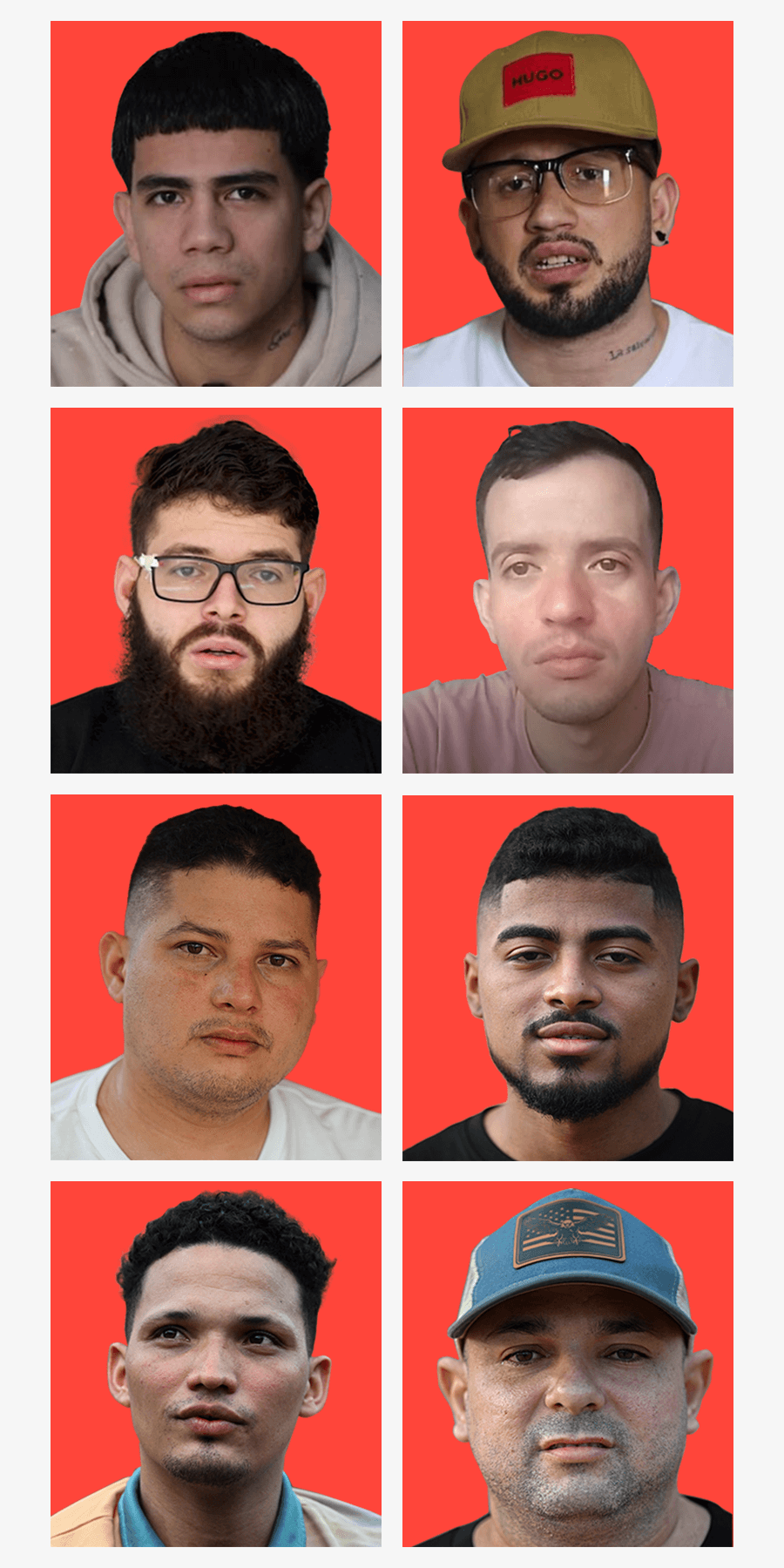

But Arturo and 251 other Venezuelans have recently been released from Cecot, having been sent there in March in a deal between the US and El Salvador, as part of President Trump’s campaign of mass deportations of migrants.

After arriving at their family homes in Venezuela last month, amid celebrations and tears, eight of the released men told BBC News Mundo about their time behind bars.

In their testimonies, they describe regular beatings, sometimes with sticks while handcuffed. One says he was sexually abused by guards.

The men say they slept on metal bunks with no sheets or mattresses and had to eat with their bare hands. They also had no access to lawyers or the outside world, and no clocks or watches to tell the time of day.

Aged between 23 and 39, they had all been living in the US. Some had entered in accordance with US law, others had crossed the border illegally, before they were accused of being violent gang members and deported to El Salvador.

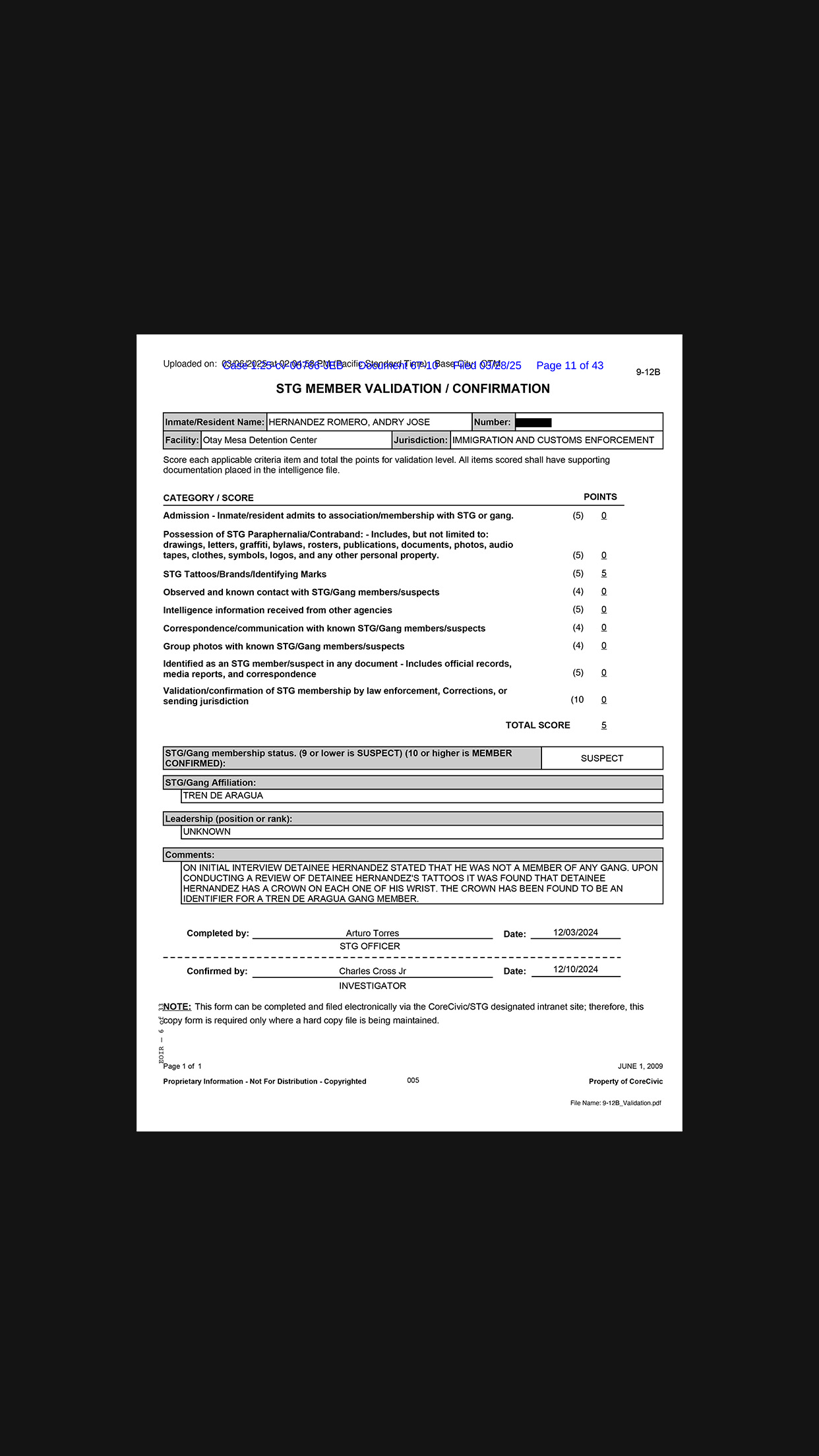

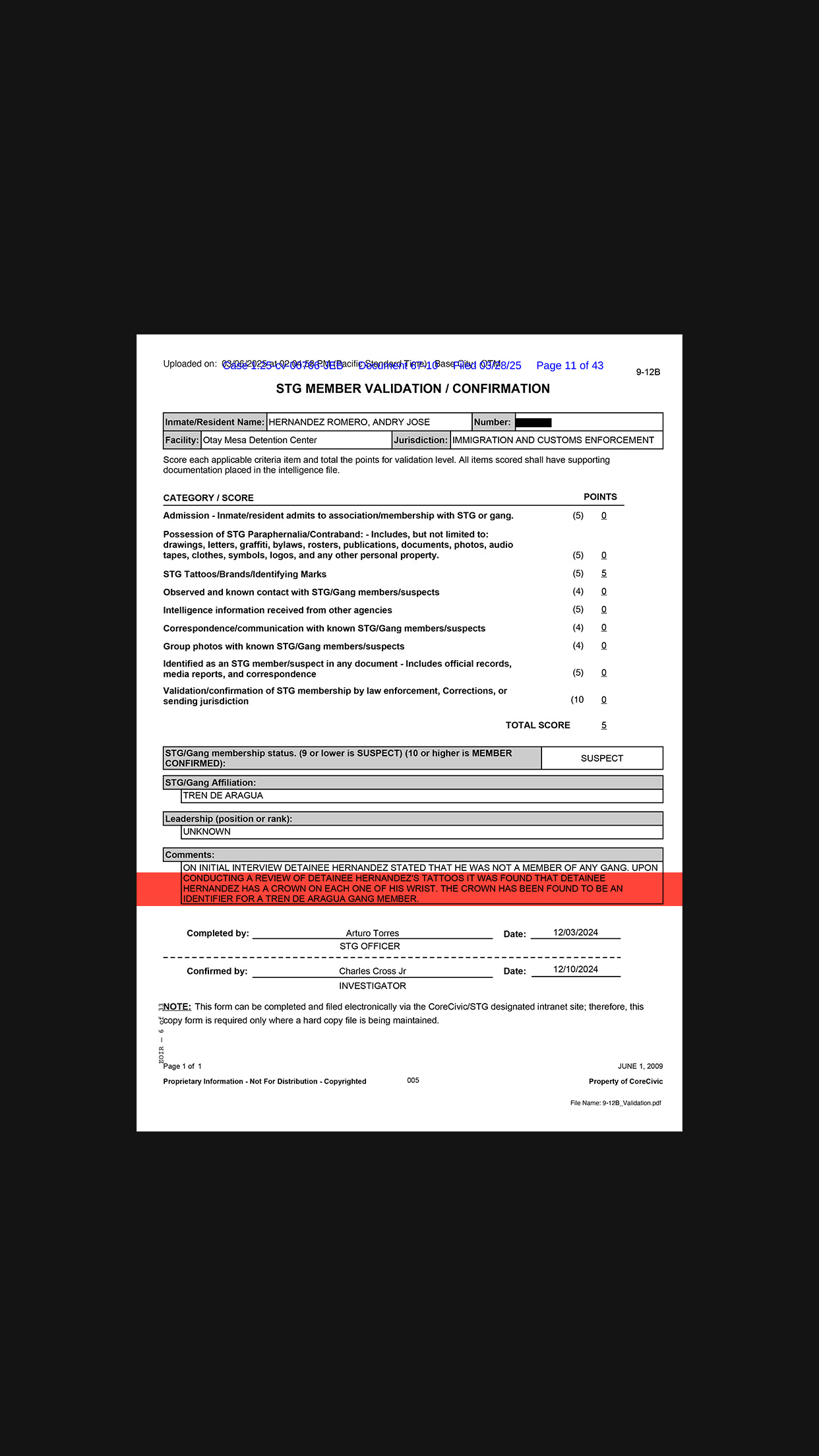

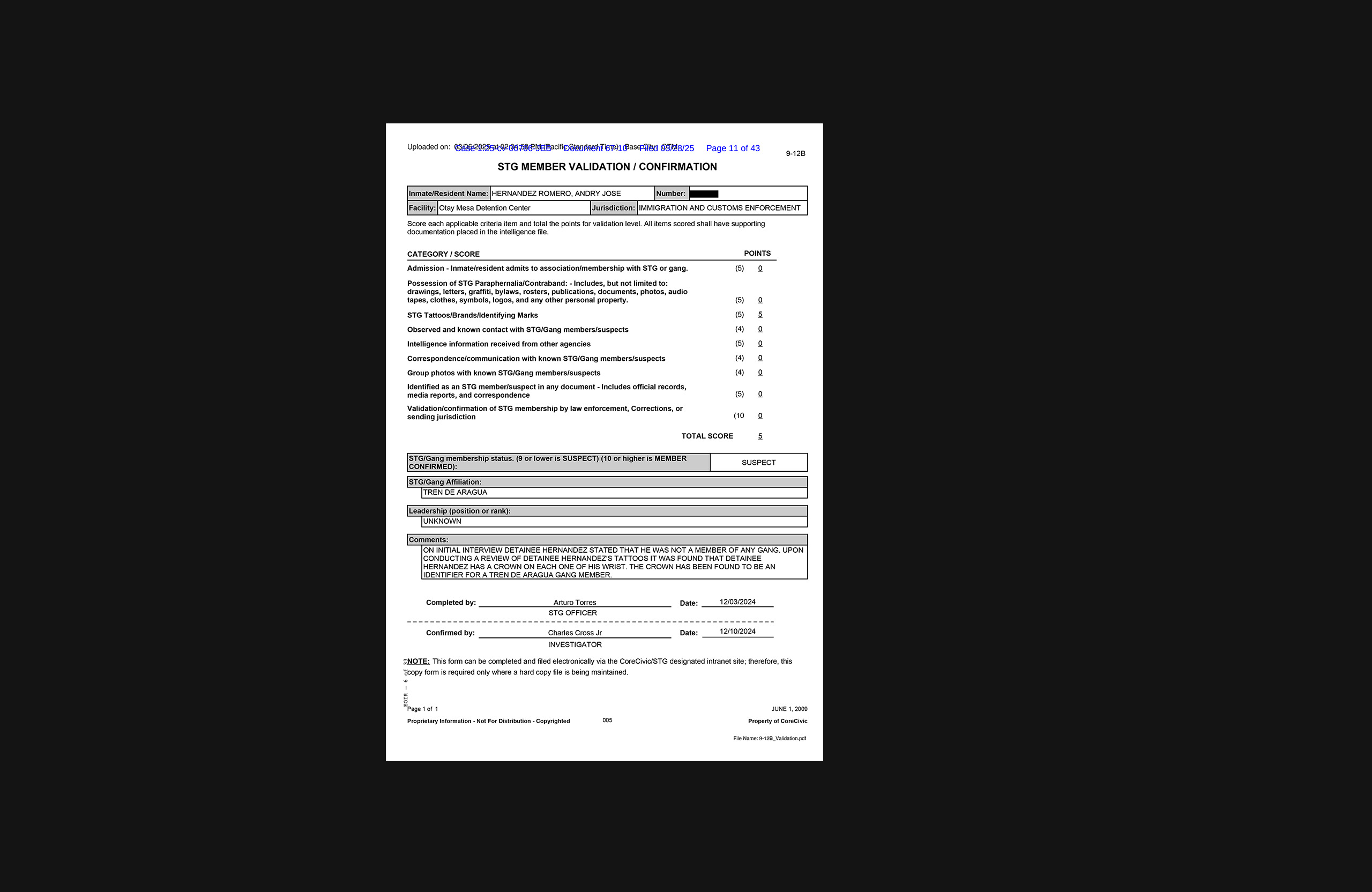

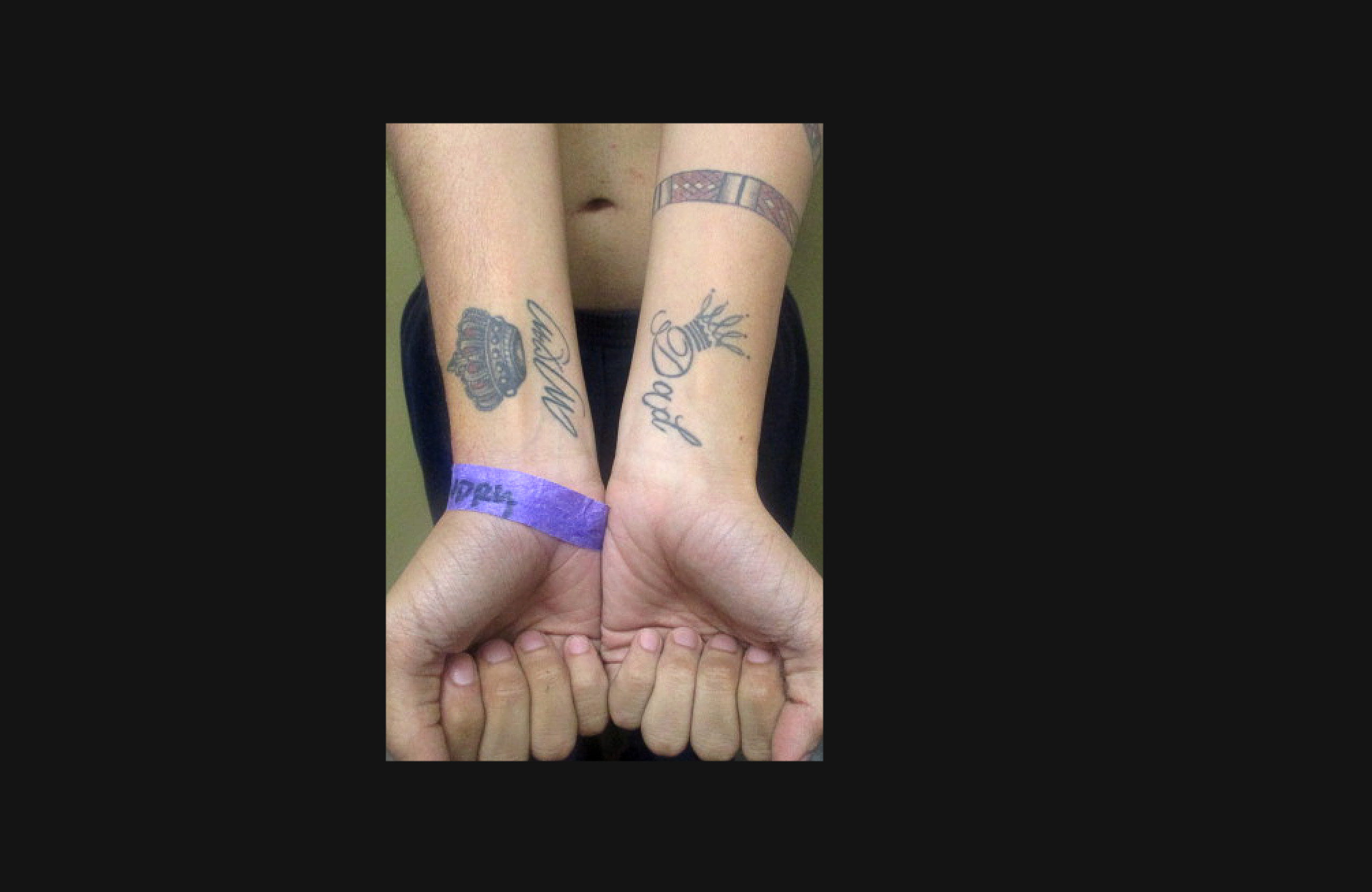

They all deny any gang involvement and criminal activity, and say they were never given an opportunity to challenge the accusations against them. Most are convinced they were singled out because of their various tattoos, which US authorities have claimed demonstrate potential links to Tren de Aragua, a powerful regional criminal group that originated in Venezuela.

The US says deportees were carefully vetted, but did not respond to questions about what evidence was used against them.

Bundled on to a plane with their ankles and wrists shackled, the men say they thought they were being flown from the US back to Venezuela. But when they landed, guards with covered faces dragged them off the aircraft, says Edwuar Hernández, and they realised they were in El Salvador.

When they arrived at Cecot, still in chains, they were forced to kneel before men who shaved their heads. They describe how they had to undress, then put on white shorts, a white sweater and white rubbery shoes.

Mervin Yamarte, who had been working in a tortilla factory in Texas until he was deported, says he was beaten while naked.

"They hit my butt with a stick, punched me in the ribs - they wouldn't let me put on my clothes."

The BBC repeatedly put the Venezuelans’ allegations to the Salvadoran government, but officials did not respond.

The prison and its cells

When they were first assigned to their cells, Ringo Rincón says a guard told them: "You know there are no lawyers here, there are no phone calls, there are no judges, there’s nothing. The only thing you have is what you're wearing and what you have inside the cell."

The Venezuelans say there were 10 to 19 of them in each cell and they were generally kept apart from Salvadoran inmates. But sometimes a group of Salvadoran prisoners would bring food and collect the rubbish, and because of their yellow uniforms, the Venezuelans called them "the minions", like the characters from the animated Despicable Me films.

The lavatory could be seen by everyone and "the smell was horrible… it stank so much inside the cell", says Wilken Flores.

"There was no ventilation, no airflow. The heat was suffocating," recounts Arturo.

The men all say they weren't allowed outside. "We felt the sun on our bodies only twice, both times when the Red Cross came," says Arturo, referring to visits the humanitarian aid group carries out in prisons to check conditions.

The daily routine

There were no windows in the cells and guards refused to tell them the day or time, the Venezuelan migrants tell us.

The men estimate their day would start about 04:00 when the guards would shout: "Counting time!"

"That was our alarm," says Andry, and the inmates would be counted before being allowed 10 minutes to wash.

In the four months he was detained, Arturo claims he was given toothpaste three times - when there were visits from the Red Cross or US politicians.

The inmates had to ask for permission to get water to drink and to go to the toilet, he adds, otherwise the guards "would hit us".

Despite having no way of telling the time, the men estimate meals were served at 07:00, 12:00 and 17:00 and were a combination of rice, beans, pasta and tortillas, sometimes with sour cream or cookies. They all say they had no cutlery and had to eat with their hands.

The guards demanded total silence, says Ringo, and if prisoners disobeyed, they would be made to stand in the "frisk position" - leaning forward, their eyes and heads down - waiting to be checked by the guards. "They would leave us like that for two, three, four hours," he says.

All the men acknowledge they could have requested a medical consultation if they felt unwell, but say they were not given any medicine during their time in Cecot, except for nine pills - six red and three white - every Monday. These were to prevent tuberculosis, they say they were told.

"Those pills made your urine red for about four days and gave it a strong smell," explains Edwuar.

The Island

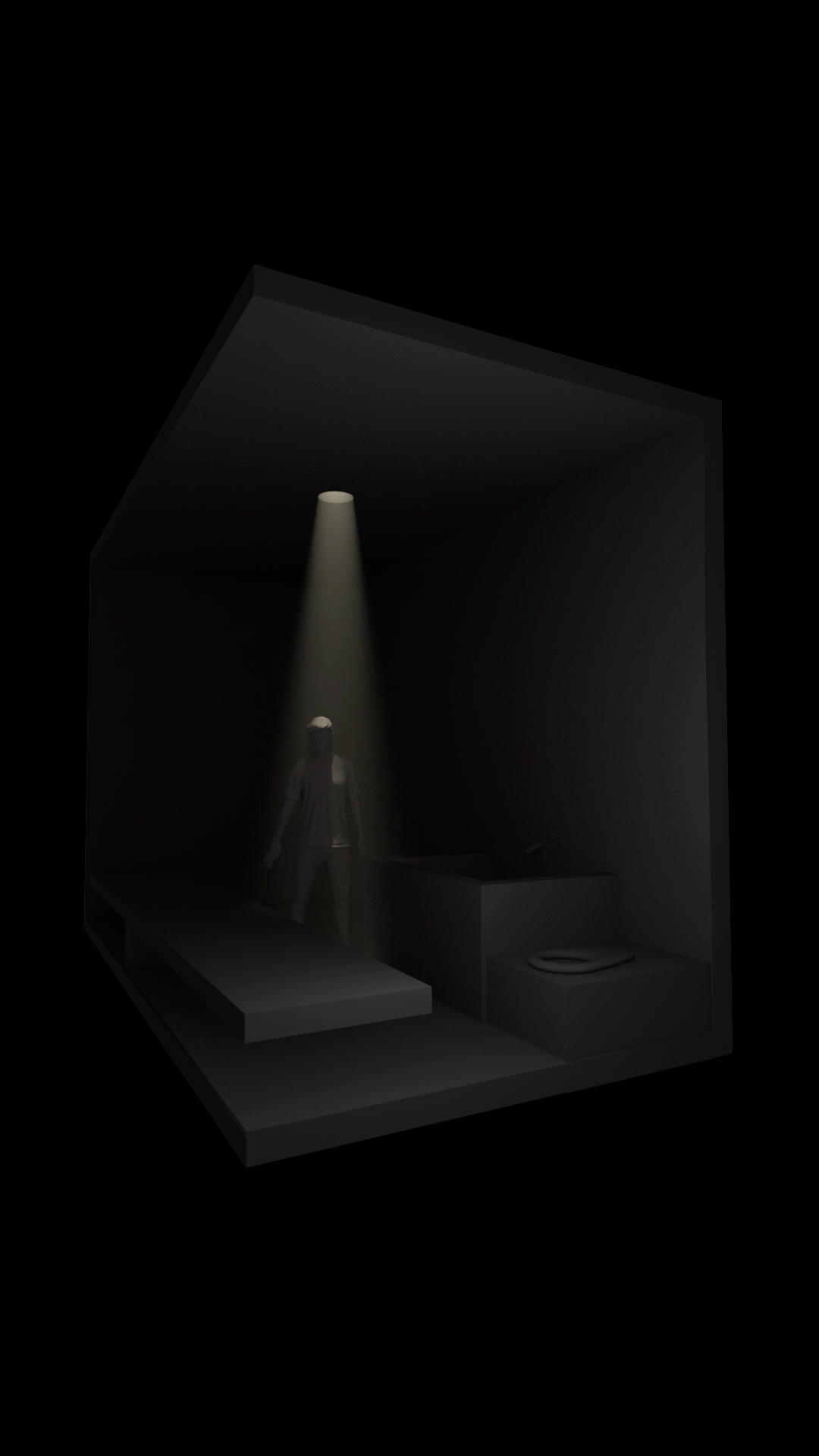

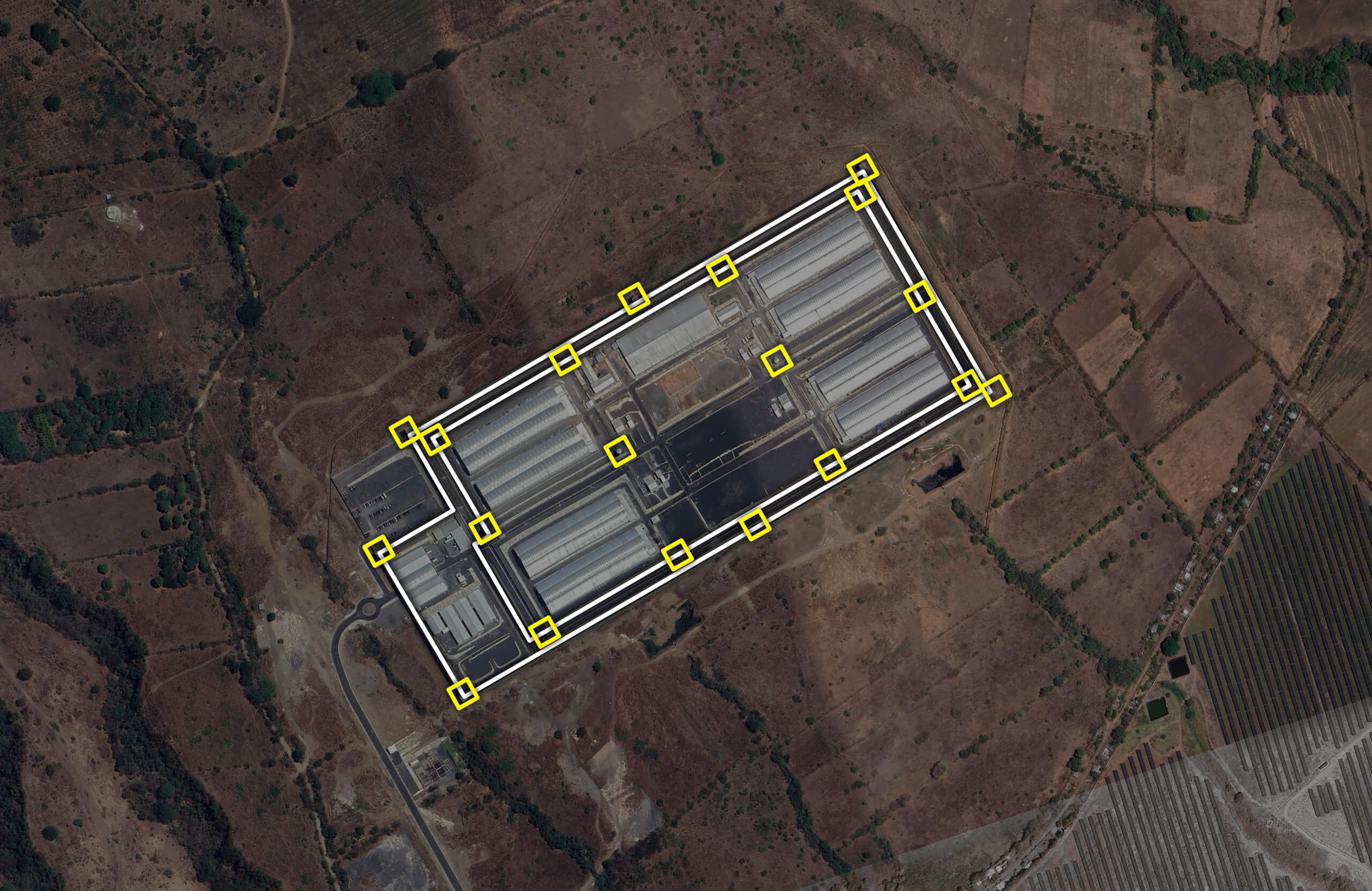

Some of the most brutal treatment is alleged to have happened in a place known as "The Island" - this is what they called each of the "three dark cells where they take you to torture you", says Joén Suárez.

The BBC has created this illustration from testimony shared by the men.

"They make you kneel, slap you, hit you, kick you," sometimes with sticks, he adds.

Arturo - a singer from Caracas - says after one beating there, he was unable to sit down because his ribs and kidneys hurt so much. "Twice I spat blood. My head was like a punch bag."

He was taken there more than 10 times, he says, mostly as a punishment for singing.

Andry says on one occasion, guards sexually abused him. He believes this was because he is openly gay.

He says he didn't dare report it to prison management because he "was afraid that something much worse would happen… that’s why we all decided to remain silent".

After about a month, locked in their regular cells, the prisoners revolted, says Joén. He describes how some of them had been made to kneel on the floor and sprayed with pepper spray - one fainted, hitting his head.

"We weren't going to let it happen again and we rose up," he says, adding that they had thrown soap and water at their jailers.

"We had a white sheet. Some of the prisoners cut themselves and used their blood to write on it: 'We are immigrants, we are not terrorists. Help. We want a lawyer,'" Joén says, describing how they had hung it through the bars of their cell like a flag. Wilken says the scars from where he deliberately cut himself are still sore.

The Venezuelans say they followed this with a hunger strike lasting about three or four days, calling for better conditions.

But nothing changed.

We put the allegations to the White House, and spokesperson Abigail Jackson responded: "The Trump Administration is grateful for our partnership with President Bukele to help remove the worst of the worst violent, criminal illegal aliens from American communities."

She said any further questions should be directed to El Salvador and Cecot.

BBC News Mundo requested interviews with the prison’s director, Belarmino García, and El Salvador’s justice minister but did not receive a response. In the past, President Nayib Bukele has denied accusations of human rights violations at Cecot and other prisons.

The visits

The Venezuelans had also tried to protest when the US Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem, visited to tour the prison in March, says Arturo.

Her office co-ordinates US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which carries out migrant detention raids and operates deportation flights - including the ones that took the Venezuelans to Cecot.

Arturo says when Kristi Noem tried to record a video of herself in front of a cell, wearing a white top and blue baseball cap, the Venezuelans in the background disrupted it, signalling for help and shouting "freedom".

He says the video she finally posted on social media, warning that "if you come to our country illegally, this is one of the consequences you may face", had a cell filled with Salvadorans behind her instead.

Asked about Arturo’s account of the visit, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) told us: "Tren de Aragua and MS-13 are some of the most violent and ruthless terrorist gangs on planet Earth. They rape, maim, and murder for sport.

"Once again, the media is falling all over themselves to defend criminal illegal gang members. We hear far too much about gang members and criminals’ false sob stories and not enough about their victims."

The DHS added that the migrants "are not US citizens and were not under US jurisdiction", once again directing queries to Cecot and El Salvador’s government.

As well as Kristi Noem, the Red Cross also visited the Venezuelans twice. Conditions briefly improved during these visits, say the migrants.

Several say they were given meat to eat or that mattresses and sheets were temporarily provided.

"They would take us out to play soccer or to worship, just for the photo," recalls Andy. "They would stop hitting us, treat us well, give us food, and take pictures, just for that moment."

And although "there was always a guard next to us", Ringo says the Red Cross visits were "the first support we felt in that place - through them, we could send messages" to relatives.

The International Committee of the Red Cross confirmed it had visited the Venezuelans twice but said it does not publicly share information about conditions in the prison "in order to maintain the integrity of the confidential dialogue it maintains with the detainees, the authorities, and their families".

Deportation

To justify deporting many of the Venezuelans to El Salvador, the Trump administration had invoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, last used during World War Two, which allows the detention and expulsion of citizens from countries with which the United States is at war.

However, a few weeks after the men were sent to Cecot, a judge in the District of Columbia ruled the act could not be used to deport Venezuelan migrants, because the US was not facing an “armed organised attack”, and he suspended flights.

Some of the men we spoke to had been applying for asylum, or were going through other official processes to be able to live in the US, when they were flown to El Salvador.

Joén says he had been given Temporary Protected Status (TPS) until April - this allows people to live and work in the US legally if their home countries are deemed unsafe. But the Trump administration eliminated this status for Venezuelans on 5 February.

Three days after this decision, Arturo - who says he had also applied for TPS - was arrested while filming a music video in North Carolina.

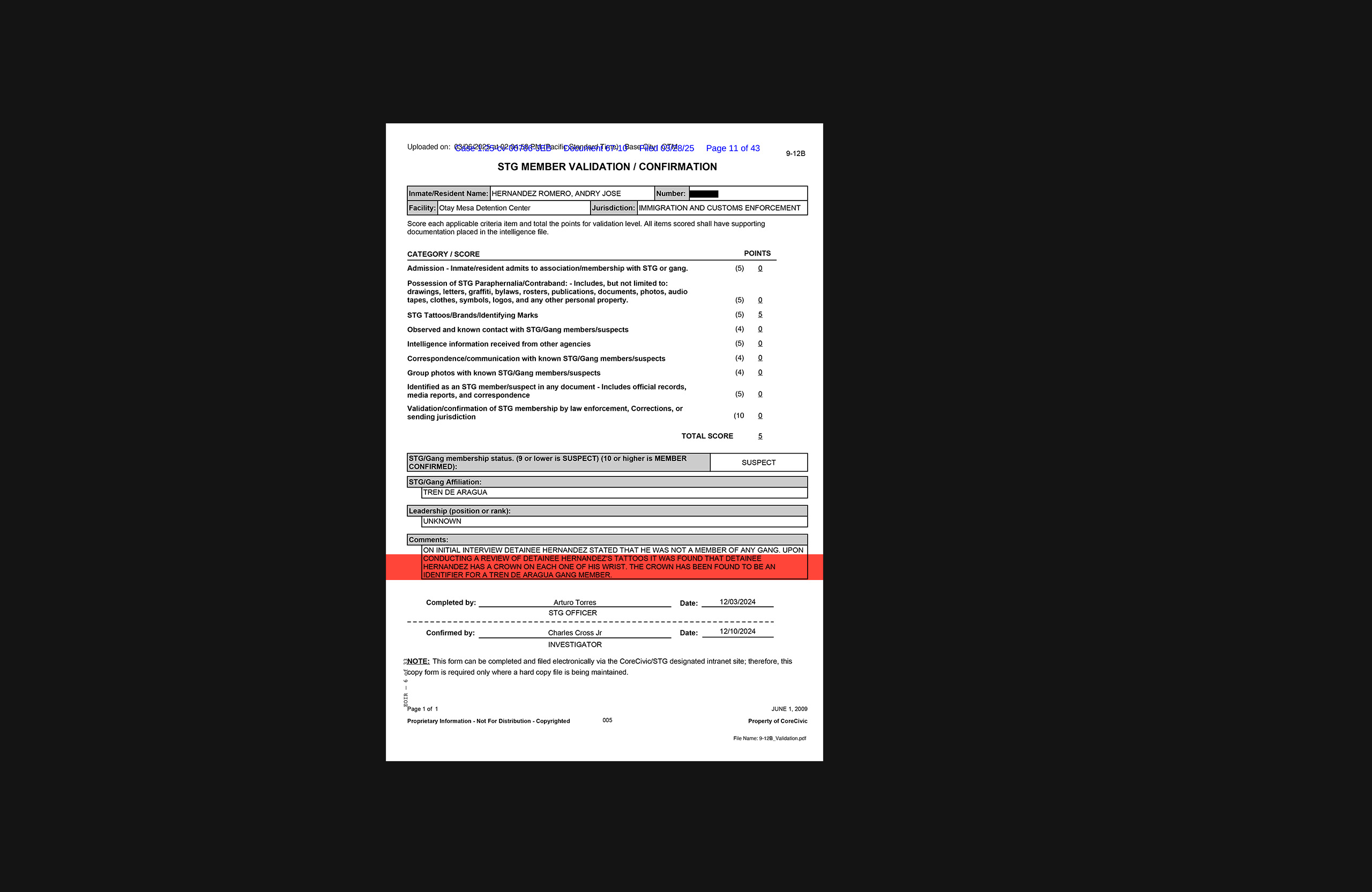

Andry, a make-up artist, had applied for asylum. In court documents, US authorities cited his tattoos as evidence he was linked to the Tren de Aragua gang.

Only two of the eight migrants we met, Wilken Flores and Andy Perozo, had been under deportation orders.

At the time of writing, another, Edwuar Hernández, is still listed in the US Immigration Court’s automated system as having a hearing pending for January 2027.

A minority of the overall group of Venezuelans sent to El Salvador have been convicted of crimes, including some violent offences, according to reports, but US officials have acknowledged that many of those deported to El Salvador had no criminal record. The BBC has been unable to find evidence in US court or other records that any of the eight men we spoke to had criminal convictions.

One of them, Joén Suárez, was charged with driving without a licence, insurance and unlawful licence plates in Colorado in 2024, but court records show the case was later dismissed.

The Department of Homeland Security did not respond to a request for further information on the men’s alleged gang affiliation, any pending criminal charges or convictions. The BBC was not able to verify claims from all the men that they had no criminal record in Venezuela.

Going home

In July, the 252 Venezuelan migrants incarcerated in Cecot were put on a bus and taken to the airport as part of a prisoner exchange that included the release of all US nationals held in Venezuela.

Realising they were being sent back to Venezuela, "we all cried, we looked at each other, we hugged", recalls Wilken. "An inexplicable joy."

Once he was home, Arturo’s family bought him some new glasses. "I spent four months not seeing properly. I couldn't read," he says.

Arturo and Andry are now planning to make a documentary about their experience.

Whenever he hears the sound of keys, Andry says his immediate thought is: "Are they coming for me? Are they going to open the cell? Are they going to punish me?"

Production and design by Visual Journalism team, Carlos Serrano and Daniel Arce. Additional reporting by Leire Ventas. Edited by Daniel García, Alison Gee, Tamara Gil and Carolina Robino. Videos of Cecot were distributed by El Salvador’s government.