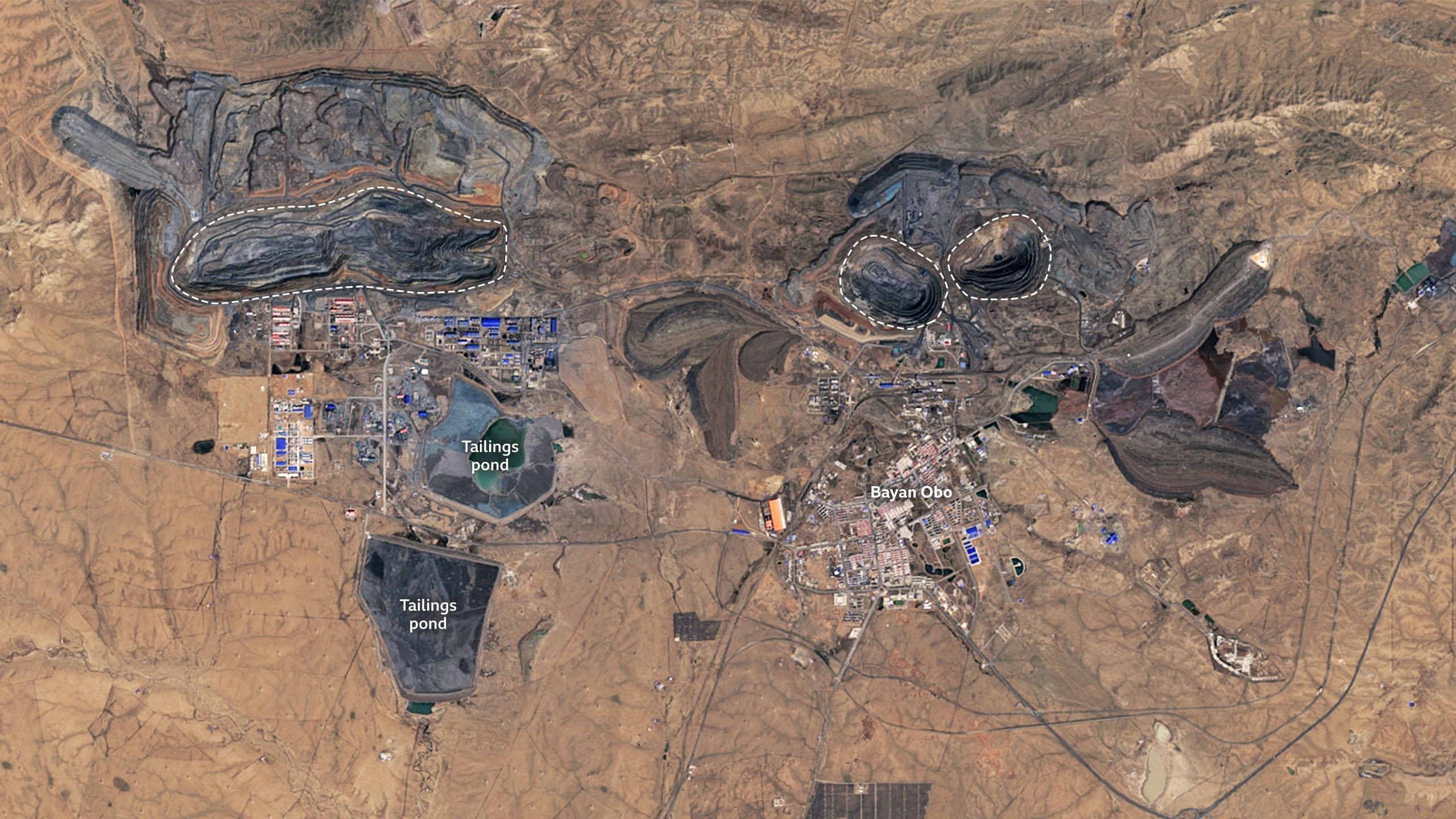

When you stand on the edge of Bayan Obo, all you see is an expanse of scarred grey earth carved into the grasslands of Inner Mongolia in northern China.

Dark dust clouds rise from deep craters where the earth’s crust has been sliced away over decades in search of a modern treasure.

You may not have heard of this town - but life as we know it could grind to a halt without Bayan Obo.

The town gets its name from the district it sits in, which is home to half of the world’s supply of a group of metals known as rare earths. They are key components in nearly everything that we switch on: smartphones, bluetooth speakers, computers, TV screens, even electric vehicles.

And one country, above all others, has leapt ahead in mining them and refining them: China.

This dominance gives Beijing huge leverage - both economically, and politically, such as when it negotiates with US President Donald Trump over tariffs. But China has paid a steep price for it.

To find out more, we travelled to the country’s two main rare earth mining hubs - Bayan Obo in the north and Ganzhou in the province of Jiangxi in the south.

We found man-made lakes full of radioactive sludge and heard claims of polluted water and contaminated soil, which, in the past, have been linked to clusters of cancer and birth defects. These journeys were challenging.

Beijing appears sensitive to criticism of its environmental record. We were pulled over by police, questioned by them and stuck in a three-hour standoff with an unidentified mining boss who refused to let us leave unless we deleted our footage.

Our calls for an interview or a statement have gone unanswered, but the government has published new regulations to try to strengthen its supervision of the industry.

Authorities have been making an effort to clean up these mining sites, scientists told the BBC. Still, China’s mining operations in the north just keep growing.

Machines are constantly on the hunt for rare earths called neodymium and dysprosium that go into making powerful magnets for a variety of modern technology, from electric vehicles to computer hard drives.

To find these rare earths, the machines strip away the topsoil layer-by-layer, kicking up harmful dust, some of which contains high levels of heavy metals and radioactive material.

Machines are constantly on the hunt for rare earths called neodymium and dysprosium that go into making powerful magnets for a variety of modern technology, from electric vehicles to computer hard drives.

To find these rare earths, the machines strip away the topsoil layer-by-layer, kicking up harmful dust, some of which contains high levels of heavy metals and radioactive material.

Satellite images from the last few decades show how the Bayan Obo mine has spread.

The mine sits in the vast, aridness of Inner Mongolia, a nine-hour drive from the capital, Beijing.

Satellite images from the last few decades show how the Bayan Obo mine has spread.

The mine sits in the vast, aridness of Inner Mongolia, a nine-hour drive from the capital, Beijing.

Further south, in the mining hub of Ganzhou, small, circular concrete ponds full of toxic waste sit on top of steep, eroded hilltops - many of the pools are uncovered and open to the elements.

These are "leaching ponds", where miners inject tonnes of ammonium sulfate, ammonium chloride, and other chemicals into the earth to separate the rare earth metals from the surrounding soil.

There were once more than a thousand mining sites, some of them illegal, dotted throughout this one county. Companies got what they needed from one mine, and then moved to another.

Then in 2012, the Chinese government stepped in to regulate, dramatically reducing the number of mining licences they issued.

But significant damage had been done to the area already. Research going back decades has linked the rare earth mines to deforestation, soil erosion and chemical leaks into rivers and farmland.

Local farmer Huang Xiaocong, whose land is surrounded by four rare earth sites, believes landslides are still being triggered by improper mining practices.

There were once more than a thousand mining sites, some of them illegal, dotted throughout this one county. Companies got what they needed from one mine, and then moved to another.

Then in 2012, the Chinese government stepped in to regulate, dramatically reducing the number of mining licences they issued.

But significant damage had been done to the area already. Research going back decades has linked the rare earth mines to deforestation, soil erosion and chemical leaks into rivers and farmland.

Local farmer Huang Xiaocong, whose land is surrounded by four rare earth sites, believes landslides are still being triggered by improper mining practices.

"The authorities’ tolerance and inaction towards what is happening… is, in my opinion, the main reason these landslides keep happening," he told the BBC.

He has also accused the state-owned company of grabbing land illegally. The firm refused to answer the BBC’s questions.

"This problem is way too big for me to solve. It’s something that has to be dealt with at the higher levels of government," Mr Huang said.

"We ordinary people don’t have the answers… Farmers like us, we’re the vulnerable ones. To put it simply, we were born at a disadvantage. It’s pretty tragic."

It is rare and often risky in China for villagers to take on huge companies - and even rarer for them to speak to international media. But Mr Huang is determined to be heard and has taken his case to the local Natural Resources Bureau.

Satellite images show the mining ponds surrounding Mr Huang's village and land. Within a six kilometres wide square, at least four sites are visible.

During our interview with Mr Huang, we were surrounded by men wearing uniforms branded with what appeared to be the logo of the same rare earth company. At least 12 other men used their vehicles to block our car from leaving.

Eventually, someone who identified himself as a local manager of China Rare Earth Jiangxi Company arrived. He confronted Mr Huang and us, and wouldn’t let us leave for nearly three hours, despite our attempts to negotiate and our offers to hear his argument.

Those living around the mines in Bayan Obo and Ganzhou appear to be victims of what used to be China’s "develop first and clean up later" approach to mining, says Professor Julie Klinger, author of Rare Earth Frontiers. That has changed now as they try harder to mitigate the damage, she adds, but the consequences are here to stay.

"I think it's very difficult to know the true human and environmental cost of that sort of development model," she told the BBC.

The worst health effects were found in and around the largest tailing pond south of Bayan Obo in the city of Baotou. In the decades leading up to 2010, villagers were diagnosed with bone and joint deformities caused by too much fluoride in the water and acute arsenic toxicity, according to Professor Klinger.

Most of them lived close to the Weikuang Dam, a man-made lake built to dump mining waste in the 1950s. Authorities have since moved villagers away from the site, but the 11km-long tailings pond is still full of grey clay sludge, including radioactive thorium.

Studies suggest this toxic mix could be slowly seeping into the groundwater and moving towards the Yellow River, China’s second-largest, and a key source of drinking water for the north of the country.

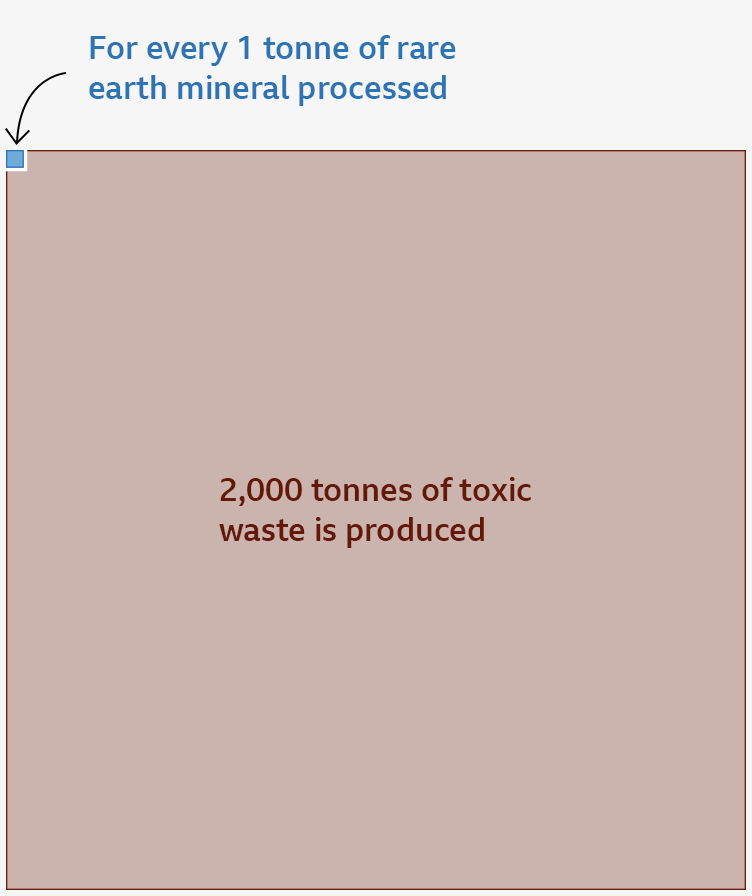

As the demand for pocket gadgets, electric vehicles, solar panels, MRI machines and jet engines surges, there is one worrying statistic to contend with - mining just one tonne of rare earth minerals creates some 2,000 tonnes of toxic waste.

China is now trying to rein in the environmental harm its rush for rare earths has caused, while expanding its mining operations abroad. Others, including the United States, are in a hurry to catch up with their own rare earth enterprises.

But scientists warn that no matter where these metals are mined, without the right solutions, landscapes and lives will be put at risk.

And yet, some farmers in Bayan Obo have adjusted to life in the the world’s rare earth capital.

The metals that have scarred their land and poisoned their water have also brought them jobs.

"With the rare earths, there’s money now," one farmer told us. "The mines pay 5,000 or 6,000 yuan ($837; £615) a month."

He says he lost money herding horses, among the traditional livelihoods in a region that has long been home to nomadic people. Horses still roam the pastures next to the mines, as diggers continue their search for more rare earths.

"Farming’s fine," he told us as he planted green onions. "You just grow your crop and sell it - simple as that."