Xinjiang Police Files: Inside a Chinese internment camp

The highly coercive and potentially lethal systems of control used against minority groups in China’s internment camps have been revealed in a giant cache of secret documents shared with the BBC.

China insists the network of secure facilities built across its far western region of Xinjiang are simply “schools” for combatting extremism to which “students” sign up willingly. But the contents of the leaked Xinjiang Police Files suggest a different story.

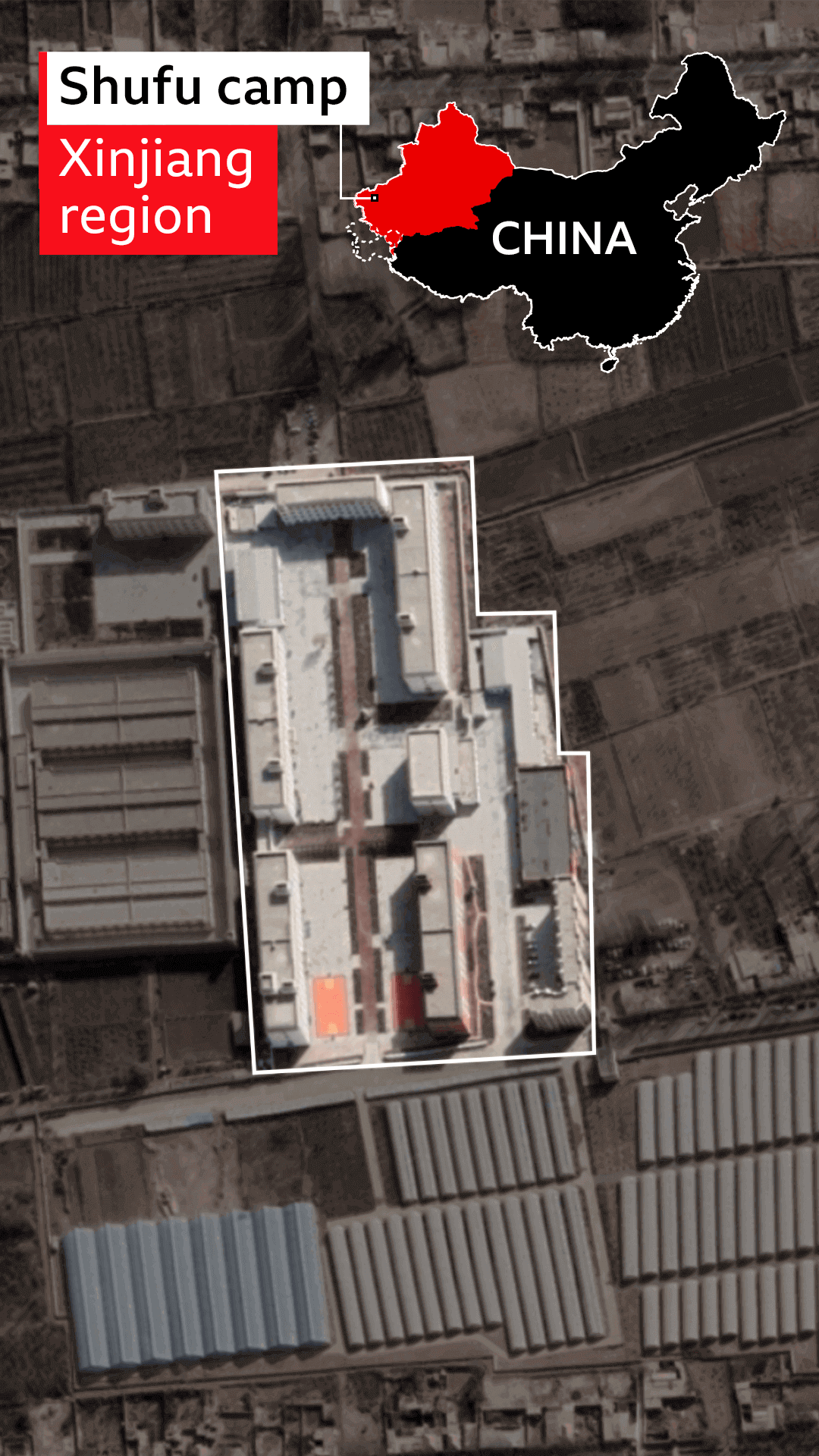

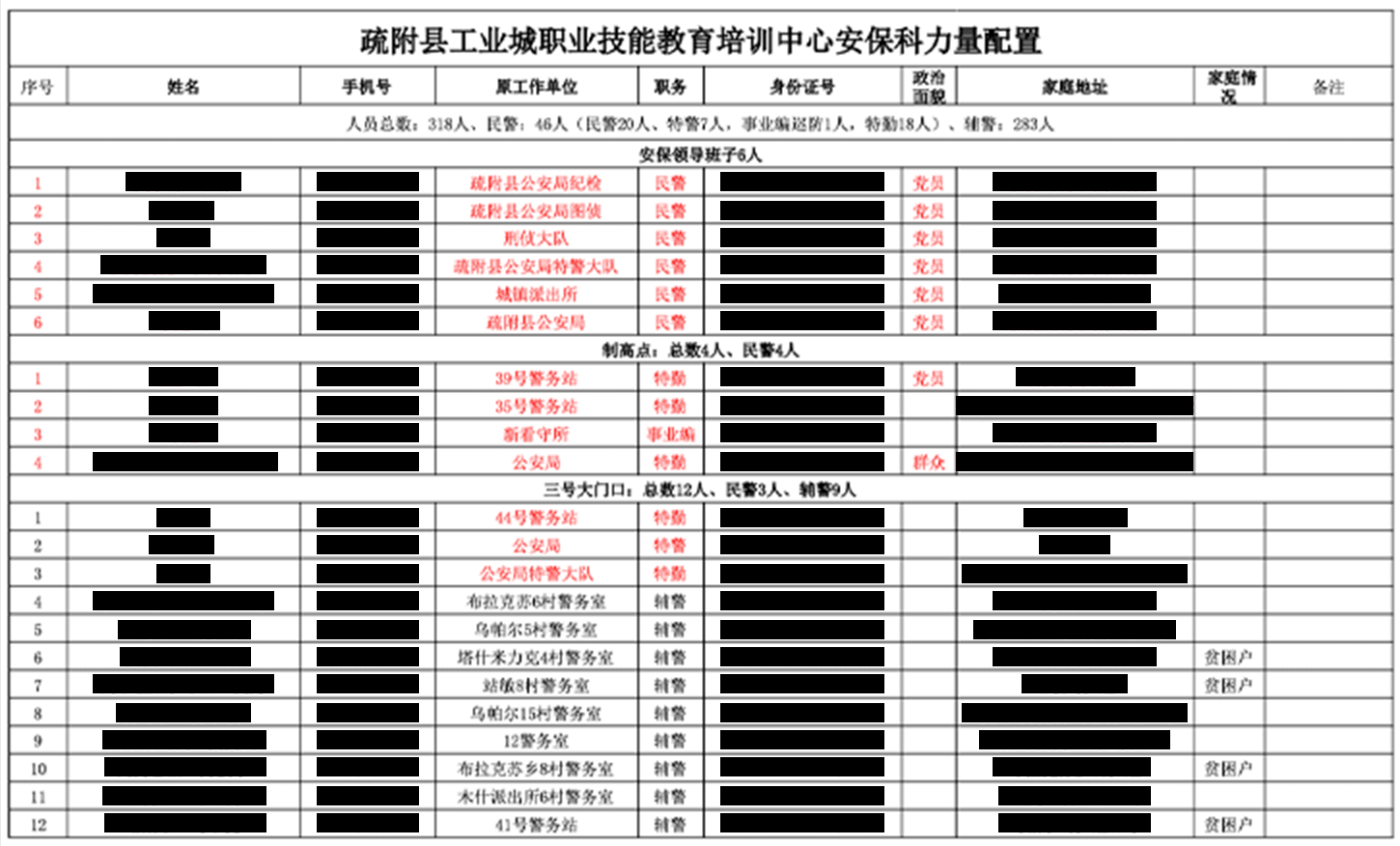

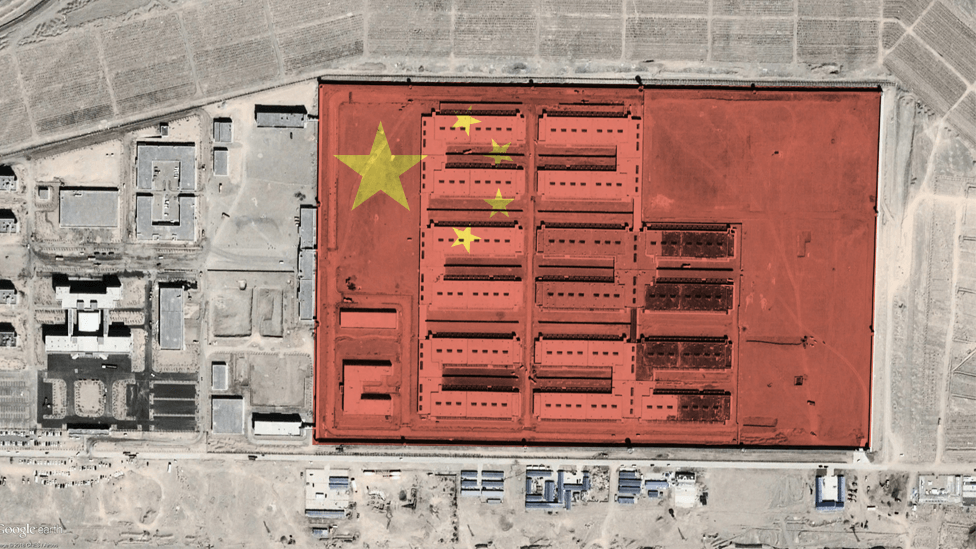

Taking information from the leaked documents, the BBC has reconstructed one of the camps – the Shufu County New Vocational Skills Education and Training Centre - to reveal the methods used inside.

The camp is just south of the city of Kashgar.

The documents show it holds 3,722 “students”, guarded by more than 366 police officers.

Police are stationed at the front gate…

…and each of the main buildings.

Watchtowers, the documents say, are guarded by two police officers.

Exercise yards are fenced off and watched over by seven officers.

Two of them have guns.

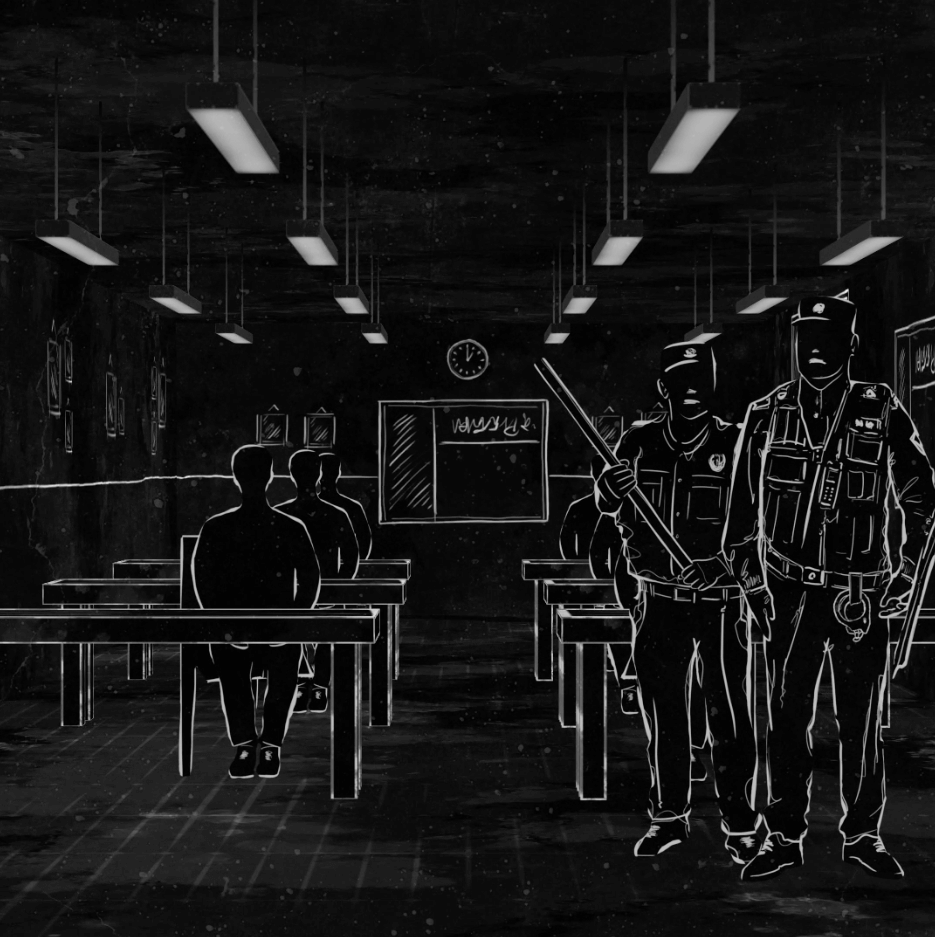

Inside the building, “students” are overseen during lessons by police.

The officers carry shields, batons and handcuffs.

The leaked papers detailing the protocols, or rules, for guarding the camps are part of a cache of tens of thousands of documents, mostly dated from 2017 and 2018.

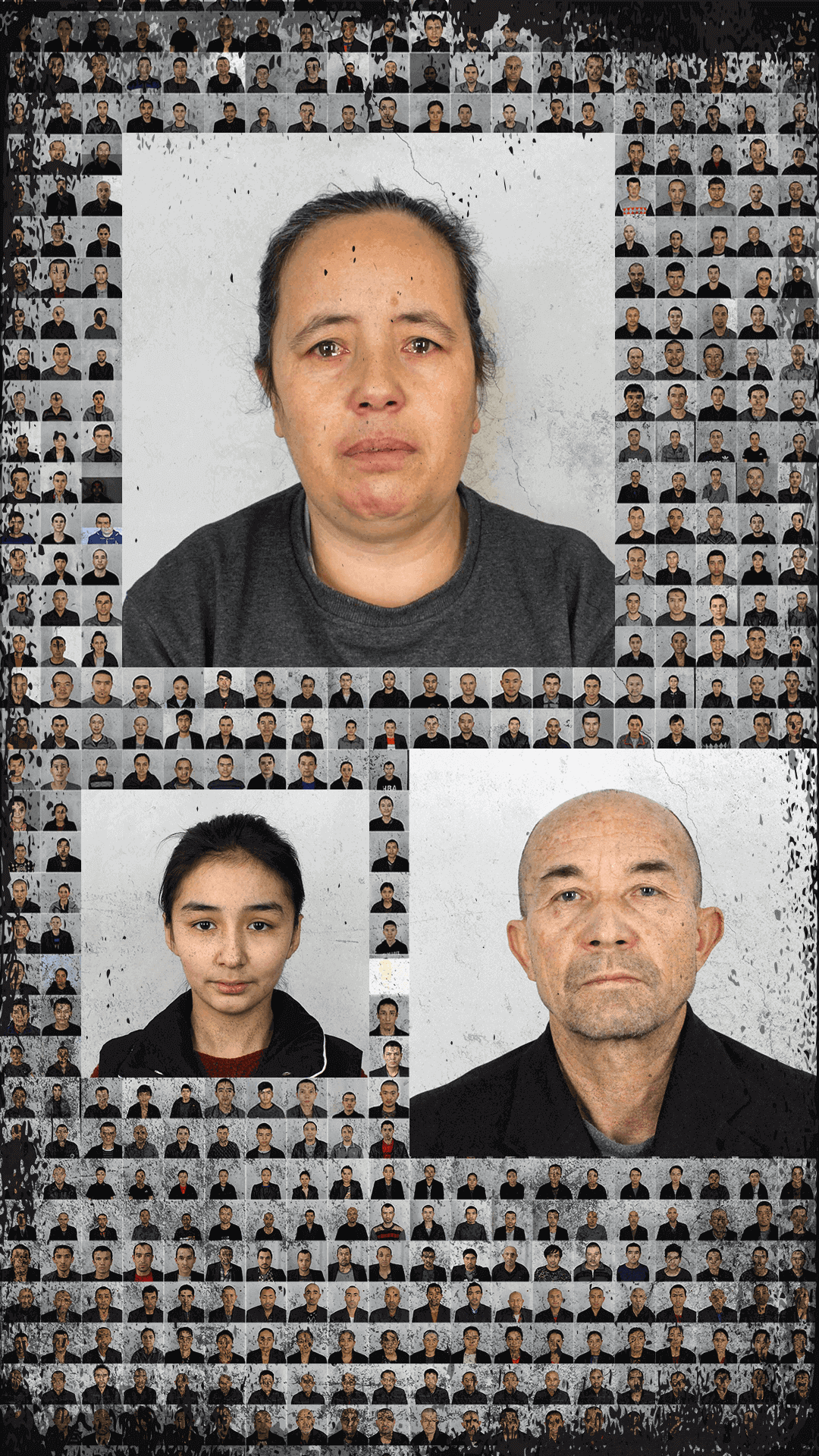

The Xinjiang Police Files - the title given to the cache by a consortium of international journalists of which the BBC is part – include classified speeches by senior officials, thousands of images of Uyghur detainees, spreadsheets detailing their internment status, and the personal information of hundreds of police officers.

An anonymous source, who claims to have hacked, downloaded and decrypted the files from a number of police computer servers in the Xinjiang region, first passed them to the US based Xinjiang scholar, Dr Adrian Zenz, who in turn shared them with the BBC.

The painstakingly detailed police work rosters, training manuals and instructions for guarding the camps show more than just the presence of guns.

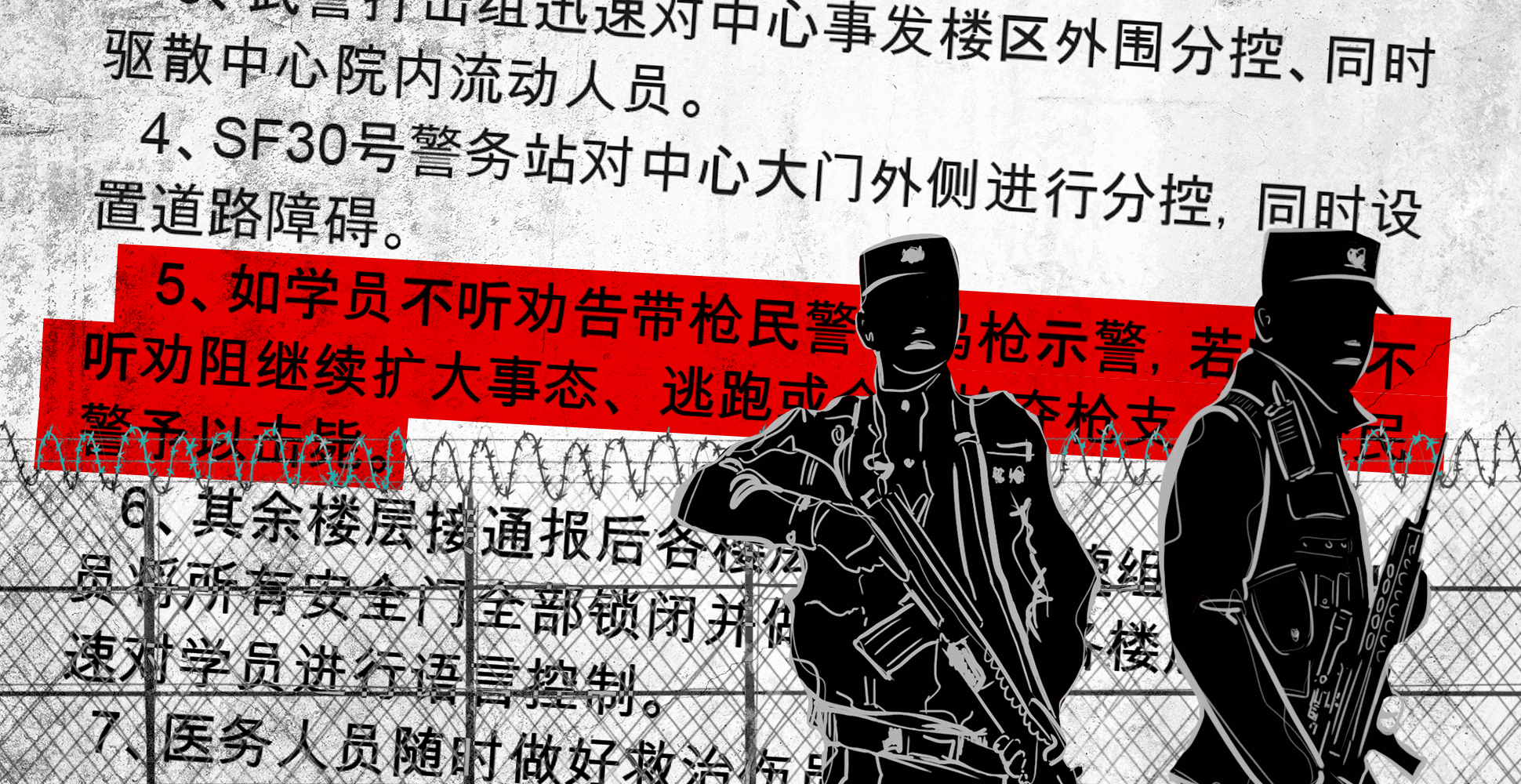

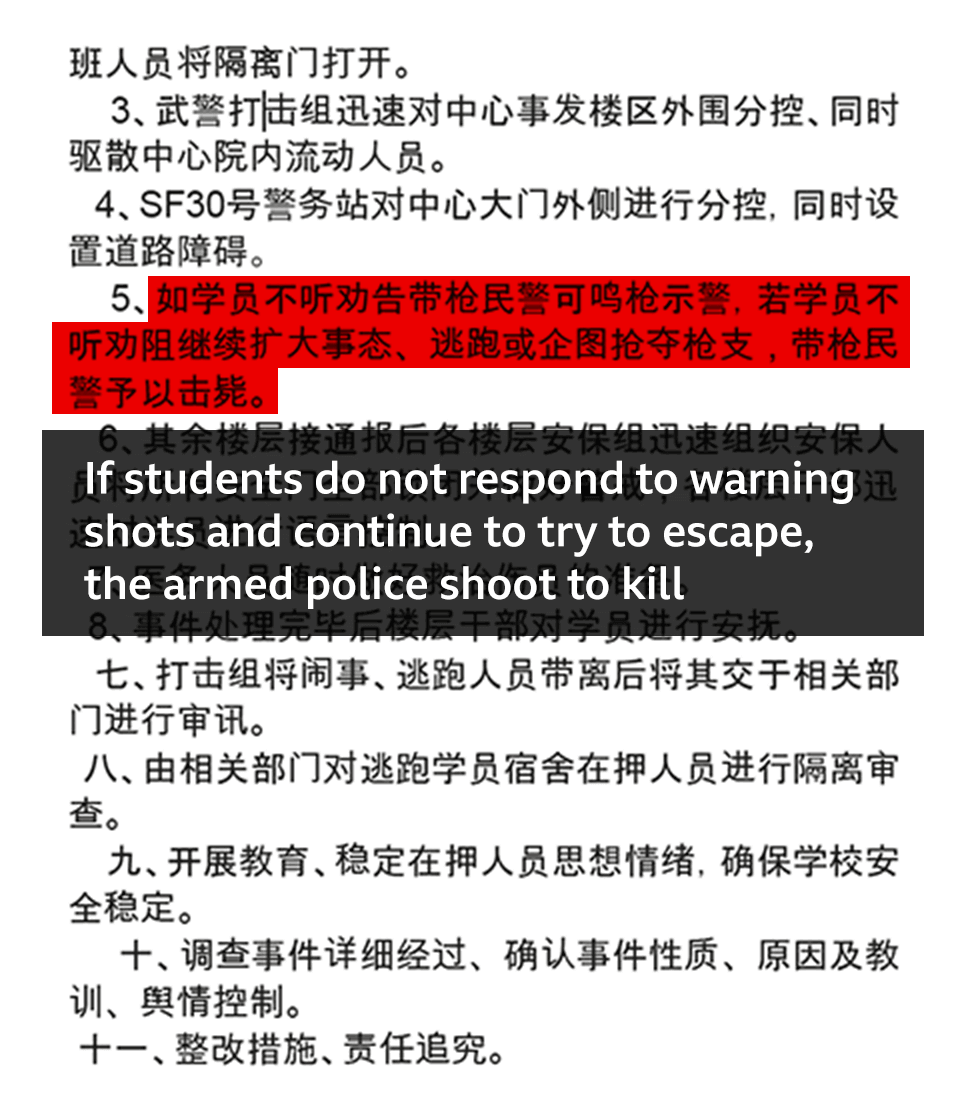

In the most significant document in this part of the dataset, officers are ordered to be prepared to use the weapons in the event of an escape.

When the alarm is triggered, the papers say, the perimeter roads must be sealed off, the buildings locked down and the camp’s own armed police “strike group” sent in.

After a warning shot is fired, if the “student” continues to try to escape, the order is clear: shoot them dead.

The documents also state that any apprehended escapees should then be taken away “for interrogation”, while camp management should focus on “stabilising other students’ thoughts and emotions” to ensure the school is “safe and stable”.

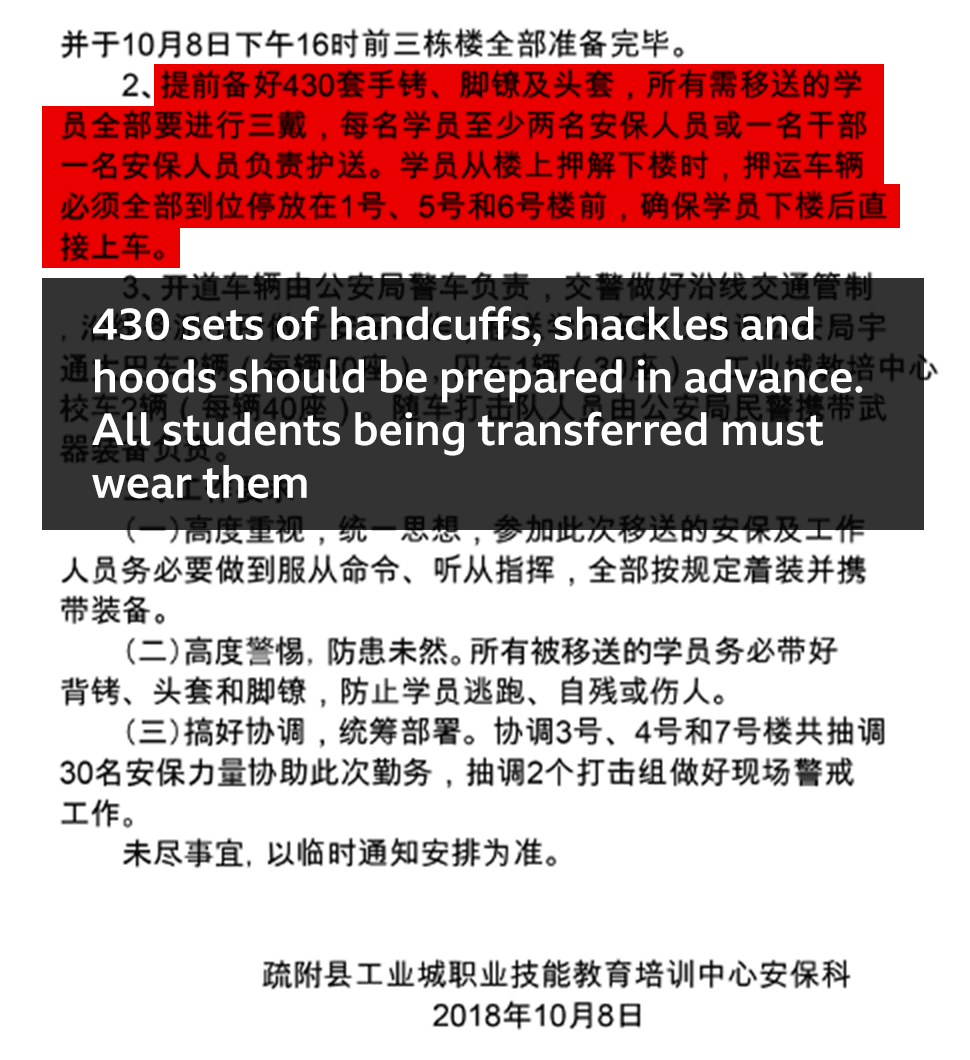

The police protocol documents also describe the rules for transfers from one facility to another.

Those being transferred should be blindfolded with their “hands cuffed” and their “feet shackled”, the papers say.

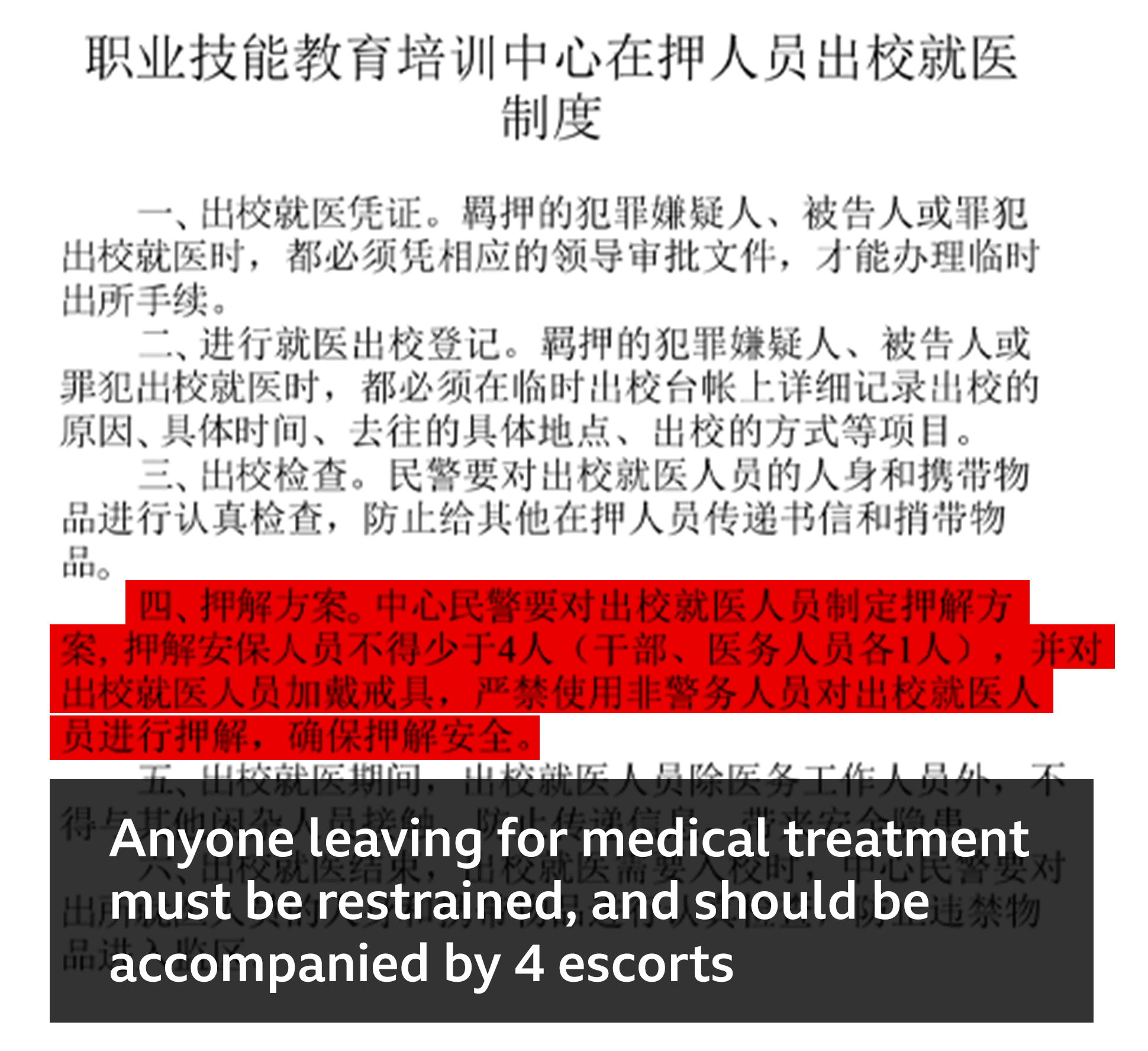

The documents reveal that even the sick must be restrained and escorted by four staff – again while wearing cuffs and shackles.

This is an approach used in other countries only for highly dangerous prisoners.

The above instructions on transferring detainees between facilities bear a strong resemblance to footage seen in 2018, which China vehemently denied had anything to do with the camps, but now appears to be given further weight as a result of the hack.

YouTube video from 2018 shows similar techniques

There’s a striking similarity between the instructions for moving the sick and an image from the hacked files, showing the highly controlled circumstances under which medical procedures are carried out, not in a camp, but in a detention centre.

China insists that the camps provide grateful and willing Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities with lessons that steer them away from the dangers of terrorism and extremism.

In some regards, they bear a passing resemblance to schools, with the rote learning of Chinese and the reciting of propaganda slogans.

But the cache goes further than ever before in showing the harsh, involuntary nature of these facilities designed to target almost any aspect of Uyghur identity, and replace it with an enforced loyalty to the Communist Party.

Although the police protocols - which are written in simple Microsoft Word files - are difficult to independently verify, they sit alongside many other documents that are far easier to authenticate.

The hacked data contains thousands of photographs of people who have been incarcerated – many of which also show evidence of a high degree of control with officers carrying batons visible in some of the images.

These images can be verified by being shown to contain real people, identified as the missing relatives of a number of overseas Uyghurs approached by the BBC.

The BBC has also been able to verify the spreadsheets containing the photographs, ID numbers and cell phones for camp police officers.

Although security personnel in Xinjiang are known to be under orders not to answer calls from overseas, after dialling the numbers listed for more than 150 police officers and government officials, several picked up and confirmed their names, roles and respective offices.

Transcript of call to police mobile phone number

Hello, is that police officer [name] ?

Yeah, what’s up?

Are you the police officer who works at the Tokzak Township police station?

Yeah, who are you?

May I ask, have you worked at the Shufu Industrial Park Vocational Skills Education and Training Centre?

Who are you?

I would like to verify a piece of information with you.

What do you want to verify? Who are you?

I am the person who is calling you.

What the [expletive] do you want to verify?!

(Officer hangs up call)

In 2019 China began to claim that most of its re-education camps were closing and the “students” had all graduated.

But the evidence suggests that many remain operational or have simply been renamed as formal prisons or detention centres, in an attempt to dampen the international criticism.

After approaching the Chinese government for comment about the hacked data, with detailed questions about the evidence it contains, the media consortium received a written response from the Chinese Embassy in Washington DC.

“In the face of the grave and complex counter-terrorism situation, Xinjiang has taken a host of decisive, robust and effective deradicalisation measures,” the statement said.

“As a result, Xinjiang has seen no terrorist case for several years in a row,” it went on, claiming that “a large amount of false information had been spread on the Xinjiang issue” in recent years.

“The local people are living a safe, happy and fulfilling life,” it added.

But the statement offered no detailed responses to any of the specific evidence raised by our questions, such as one document that suggests that responsibility for the highly coercive methods of control and the shoot-to-kill policy rests with some of the Communist Party’s most senior officials.

The cache contains the transcript of a secret speech given in May 2017 by Chen Quanguo, until recently Xinjiang’s Communist Party secretary.

On the one hand, Mr Chen insists that Uyghurs are the beneficiaries of the great love of the party, but on the other, he urges his audience to treat those returning from abroad “as criminals” to “arrest, detain, handcuff and shackle them without exception".

And he tells the assembled police and military officials that they should “shoot dead” anyone who even attempts to escape.

Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide?

Who are the Uyghurs and why is China being accused of genocide?

Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape

Uighur camp detainees allege systematic rape

What's happened to the vanished Uighurs of Xinjiang?

What's happened to the vanished Uighurs of Xinjiang?