Buried without a name

The untold story of Europe's drowned migrants

More than 1,250 unnamed men, women and children have been buried in unmarked graves in 70 sites in Turkey, Greece and Italy since 2014, a BBC investigation has found. The majority died trying to cross the Mediterranean to seek a new life in Europe.

Over the past two years an estimated 8,000 people have lost their lives trying to cross into the EU, according to figures from the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Most are lost at sea, but many bodies have been washed ashore, bringing tragedy to the beaches of Greece, Italy and Turkey.

But who cares for these dead? Where are they buried? And how can desperate relatives many miles away discover if their missing loved ones are among the drowned?

Ten people a day have died trying to cross the Mediterranean, since 2014.

On average, at least one person each day has been buried in an unmarked grave.

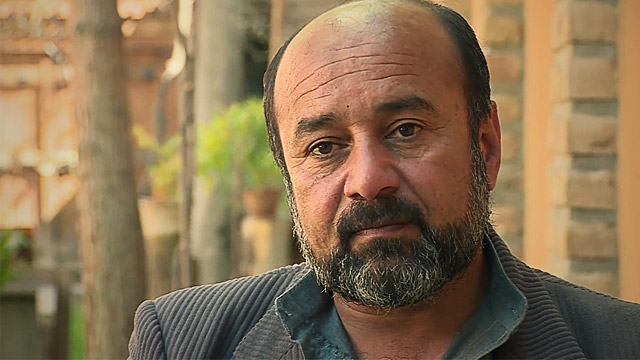

Farouk's story

In less than six months, Farouk's beard turned from black to grey.

It was 28 October 2015, when he spoke on the phone to his brother Ghulam for the last time.

Threatened by the Taliban, Ghulam Nabi Pakar, a veterinary surgeon, had decided to look for a safer home in Europe with his wife, three sons and daughter.

From his house in Herat, Afghanistan, Farouk listened to his brother Ghulam explain that the family had made it to Turkey. They were waiting to board a smuggler's wooden boat they hoped would take them to the Greek island of Lesbos. He promised to call again when they arrived.

The family were following the same route as more than half a million others who attempted the sea crossing from Turkey to Lesbos that year.

After several hours with no news from his brother, Farouk called the smuggler who had arranged the crossing. He was told the terrible news that the boat had capsized.

But the smuggler said most of the passengers had been rescued and that Farouk should wait for a phone call from Ghulam. The phone call never came.

To his horror, Farouk saw the body of his brother in a photograph. He was lying dead on a beach in Lesbos.

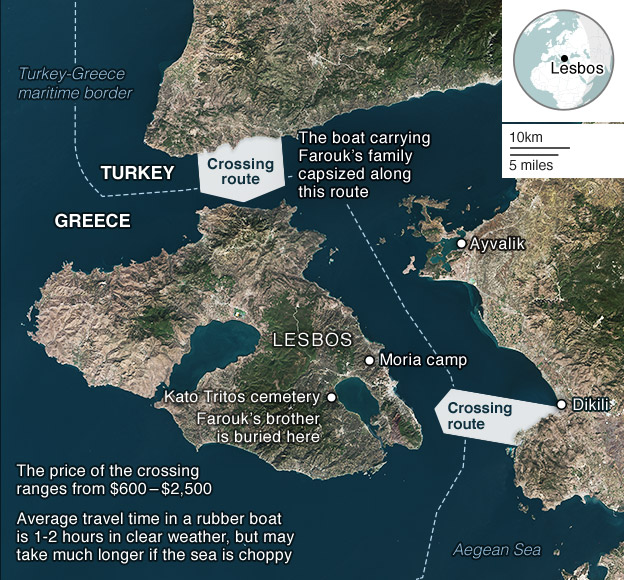

The 10km sea-crossing into the EU

NASA Landsat, BBC research

In total, 242 people were rescued from the capsized vessel that night, but dozens were feared missing.

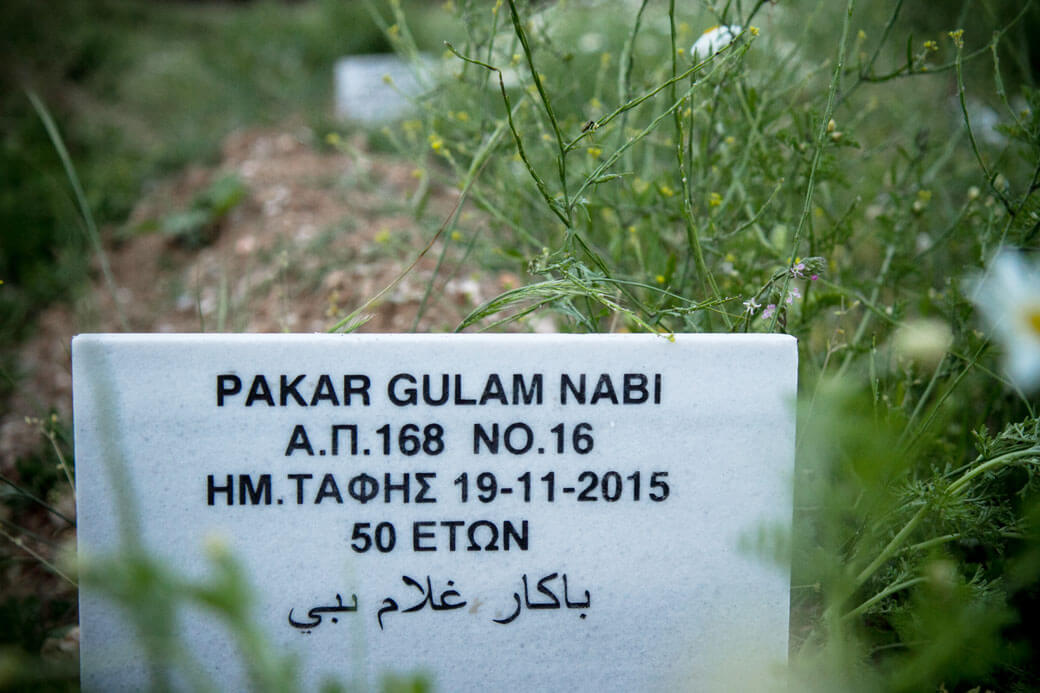

While the bodies of Ghulam, 50, and his wife, 34, were both recovered, the four children – Tamim, 16, Samim, 14, Nazella, 12, and Hasim, 10, were never found.

Farouk has not given up the hope that the children made it across the water and are now in Europe, alive. But he acknowledges they could have been lost at sea or, with no-one to identify them, buried in an unmarked grave.

Where are the dead laid to rest?

More than 1,000 migrants who have died crossing the Mediterranean have been buried in unmarked graves in Italy, Greece and Turkey.

Often bodies wash ashore days or even weeks after a shipwreck in a severely decomposed state, making the identification process difficult. In other instances entire families have drowned in the same incident, leaving no one behind able to identify the bodies.

But obtaining a precise figure for the total number of migrants buried in unmarked graves is difficult. BBC research is based on available data and interviews with local officials, but figures are likely to be very approximate.

Some local authorities in Greece and Turkey, struggling to cope with the influx of migrants and the unprecedented number of bodies drifting on to their beaches, have admitted to the BBC they have been unable to keep accurate burial records.

BBC research has also been limited to the northern Mediterranean countries of Italy, Greece and Turkey. Many shipwrecks have also occurred in the southern Mediterranean. It is likely that migrants heading to Europe have also been buried in unmarked graves in Libya, but the country's uncertain security situation has prevented data collection.

In addition, 880 unmarked graves at Kilyos cemetery in Istanbul have not been included in the total because government officials could not verify how many were those of migrants who had died trying to reach the EU.

How many have drowned crossing the Mediterranean?

338

incidents

8,412

dead or missing

70

cemeteries

1,278

unmarked graves

Central Mediterranean route

The deadliest shipwrecks have occurred on the route from North Africa to the island of Lampedusa in Italy.

The boat journeys to Malta, Lampedusa and Sicily are longer and more perilous than crossing the Aegean Sea from Turkey to Greece, with boats often unseaworthy and heavily overcrowded.

The bodies of most of those who drown are never recovered.

96

incidents

7,055

dead or missing

56

cemeteries

346

unmarked graves

Eastern Mediterranean route

About 80% of the one million migrants and refugees who arrived into the EU by sea in 2015 did so via the Eastern Mediterranean route from Turkey to Greece.

Most of those heading for Greece take the relatively short voyage from Turkey to the islands of Lesbos, Kos, Chios, Leros or Samos.

Though only 10km separate the Aegean island of Lesbos from Turkey, hundreds have drowned trying to make it across in flimsy rubber dinghies or small wooden boats.

183

incidents

1,216

dead or missing

14

cemeteries

932

unmarked graves

"There is a big gap when it comes to the people who have drowned," says Mohamedi Naiem, an Afghan volunteer and a former refugee himself, who stayed in Lesbos after arriving on a pedal boat from Turkey in 2002.

"Everyone - NGOs, governments, volunteers - focuses on those who survive the journey but rarely is anyone looking at what happens with those who've drowned," he says.

Naiem is part of an Afghan network of volunteers on Lesbos that tries to help those looking for missing relatives.

"There is a total lack of information about the number of cases of people missing or being buried under a number," he says.

"All that is known is that these people left Turkey and vanished."

Searching for the children

After he recognised his brother in the photo Farouk called his sister, who lives in Germany, to tell her the news. She travelled with her husband to Lesbos and they identified the bodies of Ghulam and his wife.

But there was no sign of the children.

"While searching online I also found a picture of the incident where a volunteer was carrying a young boy in his arms. The boy, who looked alive, was just like one of my nephews."

Farouk tried to locate this volunteer, but he was told he had left Lesbos shortly after the photo was taken. Farouk's sister and brother-in-law were able to repatriate the body of Mrs Pakar to Afghanistan.

Following the shipwreck that claimed Farouk's brother's life, Lesbos' main cemetery ran out of space for graves. As a result, local authorities set aside a plot of land next to an olive grove in the remote village of Kato Tritos for burials.

Ghulam's body was one of the first to be buried at Kato Tritos. More than 70 have been laid to rest there since, over half of them unnamed.

Farouk, desperate to know the fate of his young relatives, traveled to Turkey earlier this year in case the bodies of the children had washed ashore there.

"The incident had happened between Turkey and Greece. My brother and his wife were found in Greece, but not my nephews or niece. So I thought they could have been taken by the current back to Turkey.

"I searched an area of about 1,800km hoping to find them. I went to hospitals, coastguards… everywhere. I had their pictures with me. But I couldn't find any trace of them."

A name, not just a number

The official process to register unidentified dead migrants is similar in Turkey, Greece, and Italy. The body is photographed, examined, identifying marks recorded and a DNA sample taken.

But this process is not always followed - for example on Greek islands where there is no coroner, locals have told the BBC that unidentified migrants can sometimes be buried without being registered.

Theodoros Noussias is the coroner on Lesbos. He's often called upon from other nearby islands, to deal with a new body found at sea or on the shore.

"Sometimes I get calls from the people that are missing one of their family members. They come to the hospital to see photographs and try to identify them. Then they send their own DNA sample to the lab to see whether there will be a DNA match," he says.

In Italy the process is run by the National Office for Missing Persons. At the moment at least two-thirds of its work is dedicated to the identification of missing migrants, according to department head Vittorio Piscitelli.

Once all the information about the victim is gathered it all goes into a folder, which is then assigned a case number. This is the number that will become that migrant's new ID on their grave.

We want to give them back some dignity with a name on their grave instead of just a number. Vittorio Piscitelli, Italy's National Office for Missing Persons

"We then create a booklet for each case, with all the relevant information including any objects we may have found on the body. This booklet is sent to a number of NGOs and police stations so anyone looking may find it," says Piscitelli.

"Every day we're trying to give a name to these men, women and children that are swallowed by the sea and lose everything: their lives, future, family and even their identity," Piscitelli adds.

"These people become ghosts, with no human dignity. We want to give them back some dignity with a name on their grave instead of just a number."

Hoping for a DNA breakthrough

As well as visiting Turkey earlier this year, Farouk also visited Lesbos to look for his niece and nephews. While there he met Naiem, the Afghan volunteer.

"When he came here I took him to the police, to the hospital and to the main migrant camp of Moria, but we couldn't find any information about these kids," says Naiem.

"But there are many unidentified children who are buried in the new cemetery from that shipwreck. So I helped him send a DNA sample to Athens that we hope can give him new information about his nephews and niece."

Farouk is still waiting for the results of the DNA test.

"It is very important for me to find out if they are alive or dead. If they're dead at least we can know that they are resting in peace somewhere," he says.

Back home in Afghanistan, he is trying to obtain a new visa to return to Greece. But getting visas for Europe is difficult for Afghans and the fact he was granted one last year was considered a rare exception.

I wish that I could go back in time and lock him in a room and stop him from leaving. Farouk Pakar

But Farouk is determined to find an answer and has sold land he inherited to continue financing the search for his nephews and niece.

"If they allow us to bring back the bodies I will bring them back at any cost," he says.

"We have lost six members of our family. Our life and family has been broken."

Farouk keeps photographs of Ghulam, Tamim, Samim, Nazella and Hasim where he can see them every day.

"I told him to stay in Turkey, but he insisted in carrying on. I wish that I could go back in time and lock him in a room and stop him from leaving."

How the data was collected:

The BBC carried out research on the number of unmarked graves in Italy, Greece and Turkey during March and April 2016.

Sources include local authorities and interviews with officials, but figures are in many cases approximate. It is likely that migrants heading to Europe have also been buried in unmarked graves in Libya, but the country's uncertain security situation prevented data collection.

Data on the number of incidents where migrants have died or gone missing is from the IOM's Missing Migrants Project. It counts migrants who have died or gone missing at the external borders of states, or in the process of migration towards an international destination.

In the context of incidents where migrants are attempting to cross the Mediterranean into the European Union, missing migrants are generally presumed drowned. According to the IOM, collecting data on the fatalities during the migration process is challenging and figures are likely to be estimates. You can read more on the Missing Migrants Project's methodology here: http://www.missingmigrants.iom.int/methodology

Locations plotted on the maps are in some cases approximate.

A note on terminology: The BBC uses the term migrant to refer to all people on the move who have yet to complete the legal process of claiming asylum. This group includes people fleeing war-torn countries such as Syria, who are likely to be granted refugee status, as well as people who are seeking jobs and better lives, who governments are likely to rule as economic migrants.