Is anything left of Mosul?

The battle to save the city and its people

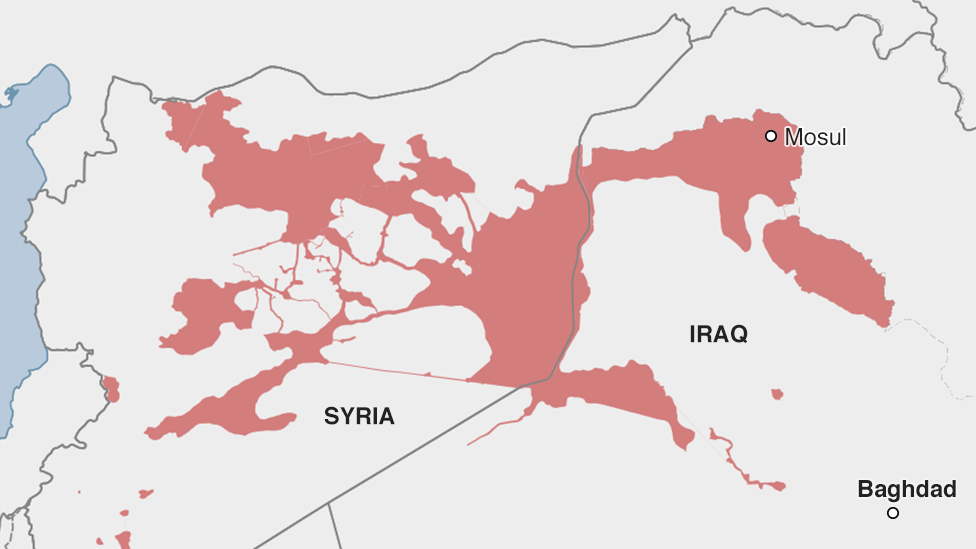

The brutal fight to rid Mosul of so-called Islamic State has left the northern Iraqi city in ruins, thousands dead and survivors scattered far and wide. Just how much devastation was caused by the battle between Iraq’s forces - backed by US-led air strikes - and the militant group, and what will happen now?

While the battle for Mosul is over after nine months of fighting, its people are facing a humanitarian crisis on a catastrophic scale.

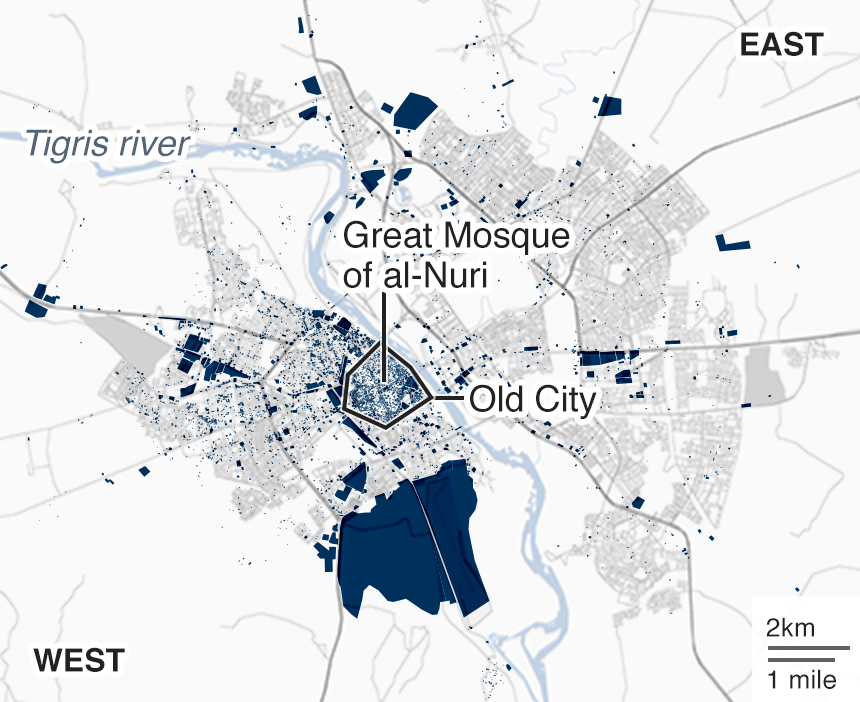

The Old City has been hit badly

Death toll estimates vary widely, from thousands to tens of thousands, and more than one million - equivalent to the population of Dublin - have fled their homes since the offensive started in October last year.

Whole neighbourhoods have been flattened, bodies remain under rubble and streets are littered with unexploded weapons, landmines and booby-traps.

Much of Iraq’s second city, controlled by IS since June 2014, has been reduced to rubble.

The mission is now regarded as the single largest urban battle since World War II.

Tale of two cities

All parts of Mosul have experienced some kind of damage, according to the latest UN assessment. However, the western half of the city, retaken in July, has suffered more than in the east - won back from IS six months earlier.

More than half of Mosul's 54 western residential districts have been significantly affected.

The UN describes 15 as “heavily damaged,” meaning most buildings are uninhabitable.

A further 23 districts are “moderately damaged,” meaning up to half of the buildings have been destroyed or are structurally unsound, and 16 districts are “lightly damaged”.

All three days and nights I was alone, shouting to anyone, but no one heard me. ‘Mama’ I kept on calling, but no answer. I didn’t know she was dead until they rescued me. Amira, 10-year-old girl rescued from her damaged home in the Old City

While UN satellite analysis suggests about 10,000 buildings have been severely damaged or completely destroyed, the real level of destruction is believed to be higher.

Taking into account damage to multiple floors of buildings, not seen via satellites, the UN now estimates the real number of damaged buildings to be more than three times greater - about 32,000.

Lise Grande, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator for Iraq, says it will take years for affected areas to return to normal.

Reconstructing the city and returning civilians to their homes will be "extremely challenging", she has warned, costing an estimated $1bn (£760m).

Building damage, October 2016 to July 2017

Numbers based on UN satellite analysis

Before offensive

135 buildings damaged (50% public, 21% homes)

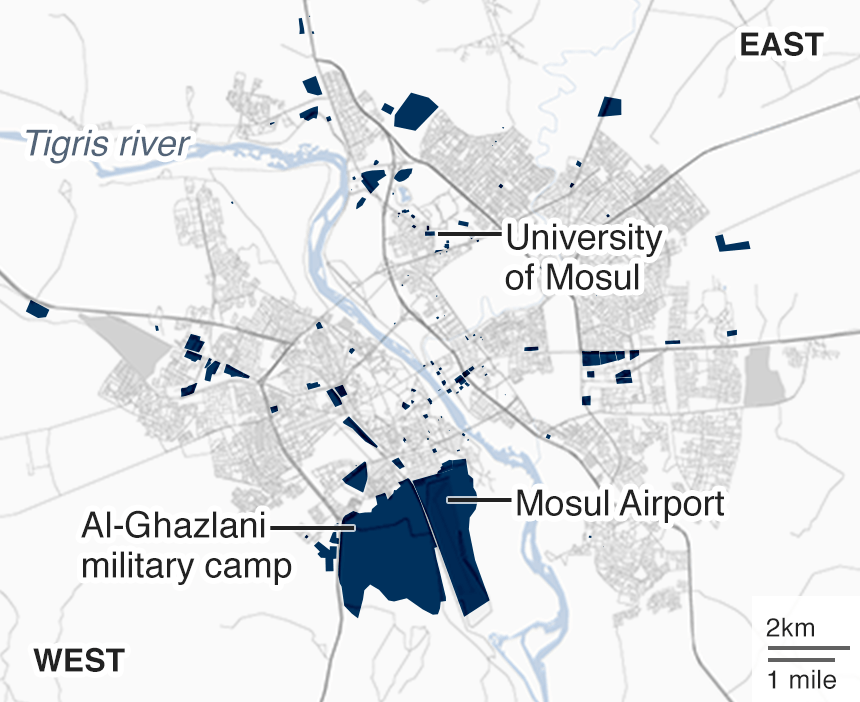

Before the offensive, many public buildings were damaged - including al-Ghazlani military camp, Mosul Airport and the city's university.

First five months of offensive

1,240 buildings damaged (47% homes)

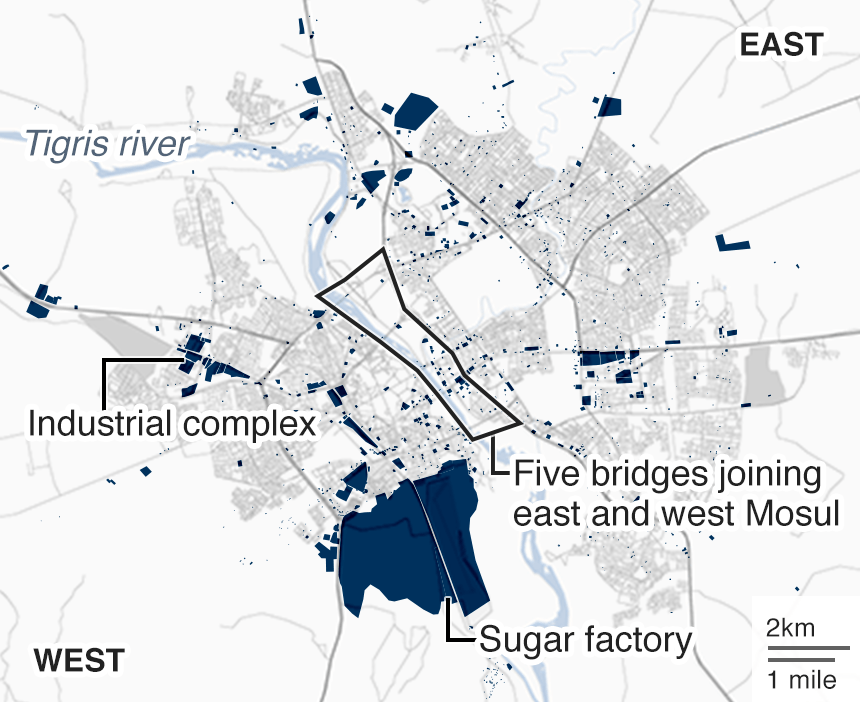

Strategic targets, such as roads and factories, were hit during the first phase of the battle. All five bridges crossing the Tigris were hit. Just under half the damaged buildings were homes.

After eight months

4,356 buildings damaged (70% homes)

In the three months from March to June this year, the number of buildings damaged nearly quadrupled - from 1,240 to 4,356. Seven in 10 of these were people’s homes.

After almost nine months

9,519 buildings damaged (85% homes)

In the final weeks of battle, more than 5,000 sites were destroyed. About 98% of these were residential buildings - largely in the Old City. The iconic Great Mosque of al-Nuri was also destroyed.

Source: UN Habitat

The UN's initial satellite analysis suggests housing has been the most heavily hit, with at least 8,500 residential buildings severely damaged or completely destroyed, most of them in the Old City. This figure is sure to increase when comprehensive damage assessments are conducted on the ground.

About 130km of roads have also been damaged overall - 100km of those are in the west.

Coalition air strikes also destroyed all bridges linking the east and west of the city across the Tigris river, with the aim of limiting the jihadists' ability to resupply or reinforce their positions in the east.

The city’s airport, railway station and hospital buildings are also in ruins.

Iraqi officials estimate that nearly 80% of Mosul’s main medical hub has been destroyed. The area was the largest health facility in the Nineveh governorate, housing several hospitals, a medical school and laboratories.

Types of buildings destroyed

Numbers based on UN satellite analysis

-

735

Roads and bridges

735

Roads and bridges

-

397

Commercial and industrial

397

Commercial and industrial

-

253

Public buildings

253

Public buildings

-

18

Sports and leisure

18

Sports and leisure

-

25

Military and security

25

Military and security

-

22

Religious

22

Religious

Source: UN Habitat

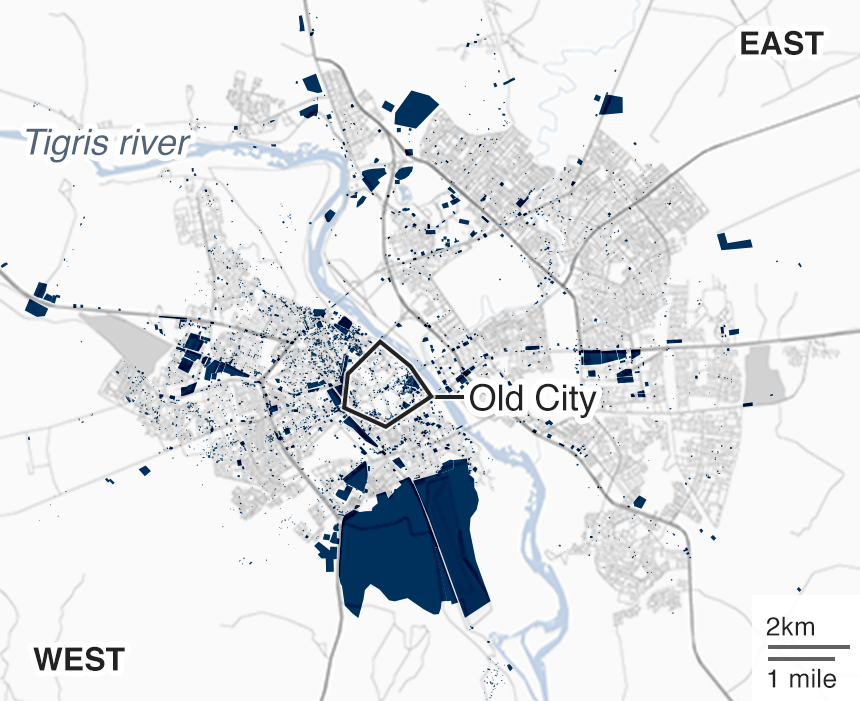

In the last weeks of the battle to liberate the city from IS, the Old City in particular was hit hard.

IS forces were pushed back into the densely built-up area after being encircled by pro-Iraqi government forces.

As the battle raged, many of the area’s residents became trapped inside their homes. When they were finally able to emerge, many were malnourished, injured and traumatised.

I was the first person to open [a hairdressing business]. I felt very proud. People warned me it could be dangerous and said I might face consequences, but luckily I had no problems. Jumana Najim Abdullah, a hairdresser who fled from west Mosul

Amira, aged 10, was among them. After mortar fire hit her house, injuring her legs and killing her mother, she was left alone.

“I kept on calling out for my mother, shouting for her to help me, but she never answered me… I could not move.”

With her father gone, trying to escape with her sisters and younger brother, Amira remained where she fell for three days.

“I had no food or water,” she said. “All three days and nights I was alone, shouting to anyone, but no-one heard me. ‘Mama’ I kept on calling, but no answer. I didn’t know she was dead until they rescued me.”

Now receiving treatment for her injuries, she doesn’t yet know what has happened to her father and other siblings.

But Amira and her family are not alone.

Satellite imagery suggests that more than 5,500 of the 16,000 residential buildings in the Old City - about one in three - have been severely damaged or completely destroyed. An estimated 490 homes were destroyed in the final weeks of the offensive.

The real figures, again, are likely to be higher.

Building damage, Mosul, July 2017

Satellite analysis shows thousands of buildings and more than 100km (62 miles) of roads badly damaged or destroyed

Source: Data from UN Habitat, image from Planet

Among the city’s iconic buildings to be destroyed was the ancient Great Mosque of al-Nuri, where in July 2014 IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi demanded allegiance following an IS declaration of its “caliphate”.

The Great Mosque of al-Nuri is in ruins

It was blown up by IS in June 2017, according to Iraqi forces. IS claimed the mosque was destroyed in a US air raid, but there was no evidence of this.

Great Mosque of al-Nuri, July 2014

Great Mosque of al-Nuri, July 2017

The mosque’s leaning 12th Century al-Hadba minaret, one of the Old City’s most famous landmarks, had survived more than eight centuries of invasion and conquest. It finally succumbed on 22 June 2017.

Al-Hadba minaret, 20 June 2017

Al-Hadba minaret, 22 June 2017

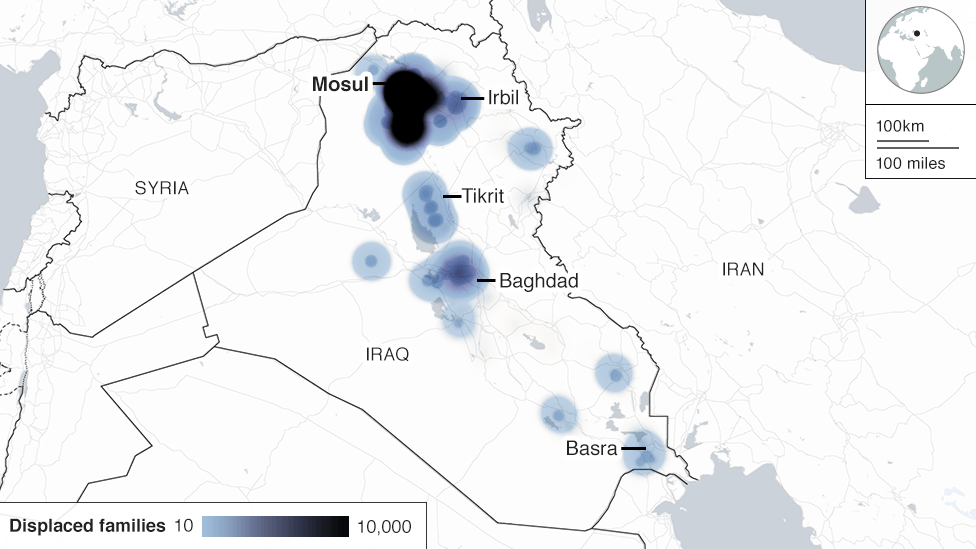

The civilian exodus

But it is Mosul’s people who have suffered the greatest tragedy.

It is not yet known how many have been killed.

The last UN estimate in January put the figure at 2,463, but since then Amnesty International has said 5,805 have been killed by air strikes alone. Meanwhile, a Kurdish intelligence report revealed to the Independent newspaper claims as many as 40,000 have lost their lives.

But with bodies still being recovered, the full death toll may not be known for some time.

In addition, one million civilians have left the city - about half the pre-war population - since the beginning of the Mosul offensive last October, according to UN estimates. More than half are children and about 700,000 are from western Mosul, the area worst affected by the battle.

It has been the largest managed evacuation in modern history.

By the beginning of August, more than 800,000 were still regarded as displaced by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), more than half of those housed in camps or emergency sites.

Others have returned to the city, are renting elsewhere, staying with friends or families or living in war-damaged buildings.

More than 440,000 people are living in camps

Source: International Organization for Migration

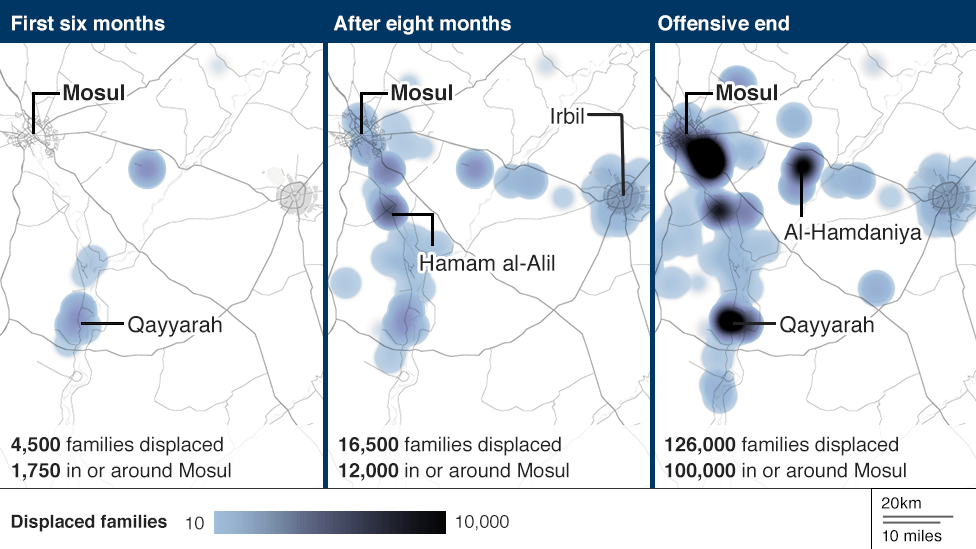

The most significant exodus from the city was during the last months of the offensive. In the eight months from mid-October last year to the middle of June, 7,000 families fled their homes in Mosul, according to IOM figures.

In the month following, that figure grew to more than 125,000 families - equivalent to a city the size of San Francisco. The number now stands at almost 140,000.

However, the recent large rise is, in part, down to the IOM merging its figures with those from local groups after the city became safer to enter.

While many have fled Mosul’s boundaries, most people whose homes have been destroyed haven’t actually left the city. More than 100,000 families remain displaced within Mosul itself.

The population of the east of the city has doubled, according to UN partner organisations, with families from western Mosul choosing to move in with relatives or friends in the east, rather than move to displacement camps.

Among those to make this move was Jumana Najim Abdullah, a 35-year-old hairdresser, who fled the fighting in the west to stay with family in the east.

Jumana, a divorced mother, was banned from practicing her trade under IS rule, but managed to earn some money by cutting the hair of known and trusted clients within the safety of their homes. Now, with the militants gone, she has moved into a rented apartment and started her own business, Jumana Salon.

“I was the first person to open”, she says. “I felt very proud. People warned me it could be dangerous and said I might face consequences, but luckily I had no problems.”

And, she says, with her daughter now back in school, she intends to stay put in the east of the city.

“Even though this is not my original home, I will stay here now,” she says. “Our former house in west Mosul is destroyed.”

Unlike Jumana, many families chose to flee the city entirely to escape the fighting. Of those families who left, nearly 3,000 have headed for the capital, Baghdad.

Irbil, an-hour-and-a-half drive to the east of Mosul, is host to 2,000 displaced families, while a further 1,000 have headed south to the Salah al-Din district, a shorter journey than to Baghdad.

When and where people fled

Source: UNHCR

When the offensive to recapture Mosul began in October, IS still controlled large swathes of northern Iraq, so those who managed to flee during the early parts of the battle headed far south.

As the Iraqi army closed in on the Old City, it became safer for families to resettle in nearby towns, such as Irbil, and the southern suburbs of Mosul.

The full scale of the damage became clear in July when the city was recaptured. 126,000 families had been displaced over the nine month conflict. About five in six remain in Mosul or its surrounding towns.

What now for Mosul?

Now the city has been retaken, Iraqi government officials and their partners are turning their attention to getting the once bustling metropolis up and running again.

But the challenge is immense - especially in the west.

To turn the gains of the military victory into stability, security, justice and development, the government will have to do everything possible to give the people back their lives in society and dignity. Jan Kubis, UN special representative

While rebuilding is likely to take years and billions of dollars, the Iraqi authorities are, for now, focussing on making the city safe enough for residents to go back.

That means removing bodies, eliminating IS sleeper cells, criminal gangs and militias, reinstating essential services and clearing explosive devices.

Months of heavy combat and air strikes have littered the city with unexploded ordnance, including artillery shells and hand grenades. Large sections of Mosul have also reportedly been mined and booby-trapped by militants.

Since clearing operations began last October, about 1,700 people have been killed or injured by such explosives, according to the UN’s Mines Action Service, which co-ordinates the mission to remove them.

Nina Seecharan, Iraq director for the British charity Mines Advisory Group (MAG), said in a statement in July that the organisation had not seen landmines used on this scale in 20 years.

In three weeks in just one village east of Mosul, MAG cleared 250 improvised landmines. Most were powerful enough to rip apart a car, but sensitive enough to be triggered by a child’s footstep.

A team from the IOM, the UN Migration Agency, visiting Mosul’s now-destroyed medical city, said explosive devices littered hospital floors, while several cars containing undetonated bombs remained parked outside.

Here in Mosul, everything is gone - our jobs, our homes, our livelihoods - but we still have our souls. All our neighbors help each other. Rebuilding our city is one way to do that. Ibrahim Mustafa, Mosul resident

But, many point out, that it is not just Mosul’s physical needs that need addressing.

The city is majority Sunni and, with a Shia-led government in Baghdad with a reputation of favouring its own sectarian interests, there will be issues of trust, accountability and inclusiveness to tackle while rebuilding takes place.

The fear of retributive acts is preventing people from returning home to restart their lives, say agencies working on the ground.

And the absence of such a “meaningful political dialogue” could lead to new violence, UN special representative Jan Kubis warned when speaking to the UN Security Council last month.

"To turn the gains of the military victory into stability, security, justice and development, the government will have to do everything possible to give the people back their lives in society and dignity."

There are small signs that people are starting to come together to get the city up and running again.

Projects to get hospitals and schools open quickly, backed by the UN Development Programme, are employing residents to help clear the rubble and clean buildings ready for re-use.

Ibrahim Mustafa, who has been helping to clean a roundabout near the al-Zuhur neighborhood, believes this could be the city’s salvation.

“Here in Mosul, everything is gone - our jobs, our homes, our livelihoods - but we still have our souls. All our neighbours help each other. Rebuilding our city is one way to do that.”

Credits

Design by Joy Roxas, development by Rosie Gollancz. Uncredited imagery of Mosul devastation by Getty. Camp imagery by Reuters. Interview of 10-year-old Amira by the IOM, image by Raber Aziz. Image and interview of Jumana Najim Abdullah, by UNHCR.