Child obesity: Has one city found a solution?

Child obesity has risen dramatically in the UK but one British city thinks it has worked out how to break the trend.

Circled by housing estates, Greenhill Primary School sits on the site of an old quarry in the centre of Wakefield.

The steep banks that surround the playground have been made into an outdoor adventure park with a fitness trail and climbing ropes to help encourage children to get the recommended levels of physical activity.

A clump of trees was once out of bounds. “It had been left to get overgrown,” says Martin Fenton, who was appointed head 10 years ago. “The children were not allowed to go in.”

Today the undergrowth has been cleared and children are actively encouraged to run in between the trees and hide in the dark corners of the “mini-forest”.

The school also has an orchard and children can grow their own fresh produce, which is then used by the school’s chefs for healthy meals in the newly built kitchens.

There is even a beehive, from which the school makes its own honey.

“It is completely different now,” Mr Fenton says. “The children love playing out and running around. The school meals are better - and because the kids are growing the vegetables they are more likely to eat them. We have become a truly healthy school.”

Other areas of Wakefield have also changed their approach.

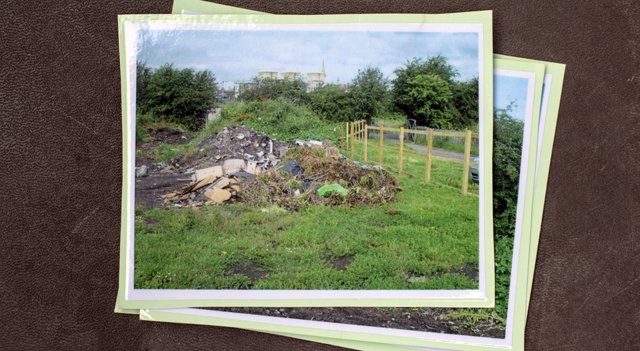

Just around the corner from Greenhill lies the Eastmoor Community Garden. It was built on derelict land that was once a fly-tippers’ paradise.

The rubbish has long since gone and you can regularly find families cooking healthy pizzas in the outdoor kitchen and locals tending to the “sensory garden” or growing a mixture of chives, lettuces and broad beans in the cottage garden.

The two sites are oases in the neighbourhood, which is one of the most deprived in the country.

They were made possible by an initiative known as the Three Area Project - TAP for short - which was launched in 2010.

The three-year project saw £2.5m invested by the council and the NHS in three communities to help encourage healthier lifestyles and reduce obesity rates.

It was a potentially controversial move. The money was found by scrapping the local child weight management programme, a 12-week scheme that worked with children who were already obese.

The organisers’ goal was clear - they wanted to prevent obesity rather than treat it.

“People were becoming dependent on it,” says Liz Blenkinsop, the council’s health improvement service manager who has overseen the project. “Some spent three years on it with little results.

"By working with three neighbourhoods that had the worst problems we felt we could find out what could really work to help stop obesity in the first place.”

Alongside Eastmoor, Airedale and the two adjoining villages of Kinsley and Fitzwilliam were also chosen. They are both former coal-mining communities that are still living in the shadow of the pit closures that took place during the 1980s and 1990s.

Local schools were supported and community venues renovated. TAP money was used to fit a new kitchen at the Kinsley and Fitzwilliam Community Centre. It now serves healthy lunches, such as jacket potatoes, salads and quiches.

“We’ve tried all sorts,” says Tracy Carrington, who manages the centre. “Soups, pastas and even frittatas - they didn’t go down well, but it is about getting people to try new things.”

But it’s also clear that there are difficulties.

While the public health team at the council has invested in the cafe, adult education classes at the centre stopped because of cuts.

Fewer people now use the centre, and the opening hours of the cafe have been cut, reducing the initiative's impact.

To the north lies Airedale. Christine Dando works in the local library. It too has got a new cafe as well as an outdoor play area for children to run around in.

Regular health checks are offered and Ms Dando says it is starting to change attitudes: “It’s gradual, but people are taking notice.”

There is an attention-grabbing display with piles of sugar cubes showing how much is in cola, energy drinks, fruit juices and milkshakes.

But habits are hard to change.

A short drive around the neighbourhood reveals plenty of young people still quenching their thirst on a summer’s evening with high-sugar drinks.

As part of the TAP drive, a team of three “activators” were employed by the project to work with the local community.

They ran activities and organised healthy eating workshops where they handed out tea towels with healthy recipes, including fresh pasta sauces and vegetable curries.

Airedale mother Tracy Millington, 48, remembers the beginning of the TAP programme. “They set themselves up on the green - and I always think if someone is doing something, trying to help you, you should take part.”

She ended up taking her three children and others from her street over to the green.

“They played football and dodgeball... It’s better than being in front of a screen all the time.”

When the three-year TAP programme came to an end in 2013 it became clear it was on to something.

The proportion of people in the areas doing moderate levels of activity had risen by more than a fifth to 34%, while the numbers describing themselves as eating very healthily rose by more than half to 16%.

The initial focus on these three areas has since been followed by a district-wide push.

The number of activators has been increased to six and the team is now working with 48 primary schools. They train lunchtime supervisors so they can encourage active play, host cookery courses for parents and put on alternative sports clubs including everything from skipping to dance.

Three of Wakefield’s biggest parks have had trails installed to encourage families to get out into the great outdoors.

The first one was introduced in Anglers Country Park and saw wooden carvings of characters from the popular children’s book Room on the Broom placed around the lake.

“The circuit is two miles,” says Ms Blenkinsop. “Parents initially said their children couldn’t walk around it. But they did. In fact, the walk became so popular the park had to hire a field off a local landowner to accommodate all the cars turning up.”

Other activities have been aimed squarely at adults.

The Castleford Tigers, one of the local rugby league clubs, has started running a health programme, inviting overweight men in for games of rugby and fitness training each week

Organised walks are also popular, particularly with older people. There are more than 40 events every week, including nine Nordic walks, where ramblers use special poles.

One of the Nordic walks is held at the local Pontefract racecourse when there is no racing.

Alan Rutter, 73, is a regular attendee. He has diabetes and suffered a heart attack a few years ago.

He now does four Nordic walks a week. The events are free and provide a rigorous all-body workout, he says.

“You push down with the poles and that strengthens your core. People don’t realise how much you exert yourself doing it.”

The changes that have been made around the area have attracted attention.

Public Health England - the government’s healthy lifestyle advisory body - has noticed the progress and is carrying out research into how Wakefield has done it.

Before the project started a third of four and five-year-olds were obese or overweight, but as it was rolled out district-wide it dipped to under a quarter, bringing it in line with the national average.

The Wakefield figures have risen since, but the council says that's because of a change in the way the measurement programme has been run.

It's clear just how hard tackling obesity is. The initial progress made in the three TAP areas has plateaued - in fact there are some signs it has gone backwards when you look at the obesity figures on a ward level, although these are classed as estimates because they cover relatively small groups of children.

It was clearly going to be hard to maintain the level of investment that was seen in those early years.

The £2.5m pot was one-off funding from the NHS and local government. With growing pressures on the health service and cuts to council budgets, there has simply not been the money available to repeat that across the region, hence it has meant stretching the support in place across a wider area.

Councillor Nadeem Ahmed, leader of the opposition Conservative group in Wakefield, says this has meant it has been left to the community - and in particular the primary schools and rugby clubs to take a lead.

“Yes the council has done some good work - I wouldn’t disagree with that - but it has only worked to a point. The really fantastic work that has made a difference has been done by others.”

There are other factors in play too. Some people in Wakefield want more restrictions on advertising of unhealthy food.

Peter Coldwell, a 42-year-old father of three, sums it up neatly. “When we pick the kids up and head home they are bombarded with advertising for sweets and pop wherever they go. Something’s got to be done.”

Much of this is outside the council’s control, requiring government action instead.

Wakefield is at a critical point. What happens on a national level will shape the tackling of the obesity epidemic.

So do areas like Wakefield need more support from government? Or is there more the council itself could be doing?

“It’s hard work. You have to be patient,” says Councillor Jacquie Speight, who has responsibility for culture, leisure and sport. “But we think we are heading in the right direction. We will keep at it.”

Credits

Pictures: Phil Coomes

Design: Prina Shah

Production: Tom Housden, Jenny Robertson

Editor: Finlo Rohrer