The village of Blatten has stood for centuries, then in seconds it was gone.

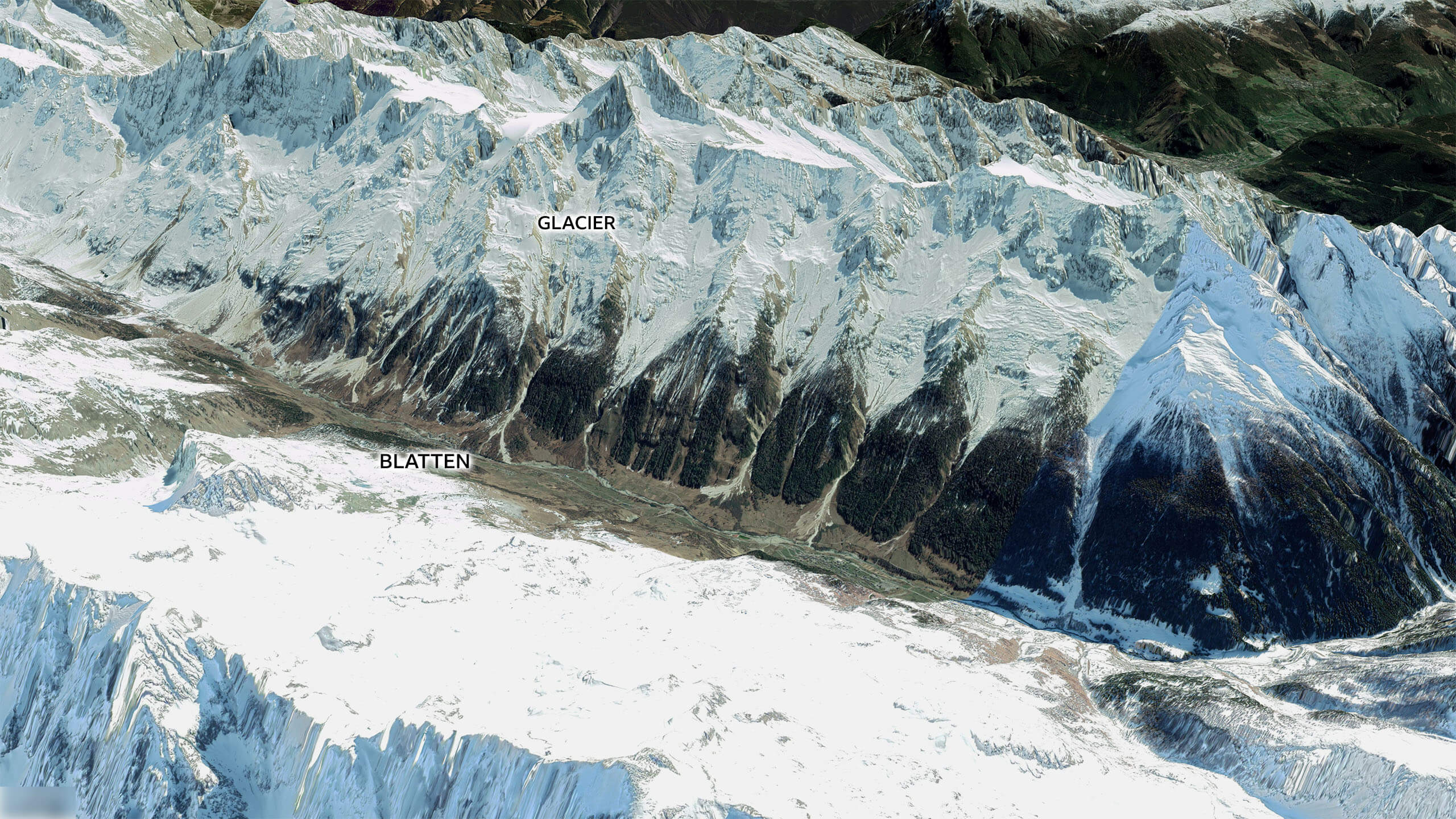

Scientists monitoring the Nesthorn mountain above the village in recent weeks saw that parts of it had begun to crumble, and fall on to the Birch glacier, putting enormous pressure on the ice.

Small rock and ice slides had begun to come down, and the village’s 300 residents, and even their livestock, were evacuated for their own safety. But everyone hoped the unstable rock would disperse incrementally over a few weeks, and that after that everyone could go home.

On Wednesday afternoon, that hope was dashed.

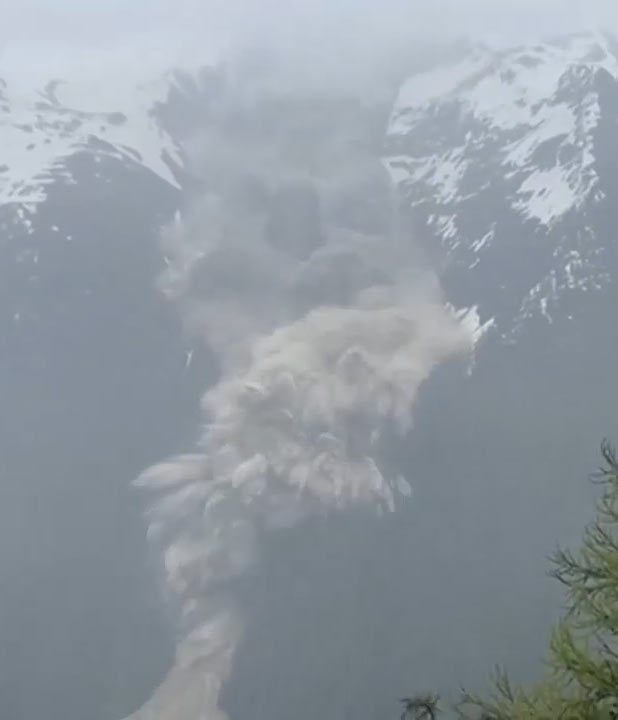

Barbara and Otto Jaggi, in the neighbouring village of Kippel, were getting their chimney fixed. The repairman was downstairs checking the system, when suddenly Barbara said: “There was loud banging, and the lights went out.”

At first, she and Otto thought the repairman had broken something, but then the banging, and now roaring, got louder, and the repairman came running up the stairs to them shouting “the mountain is coming”.

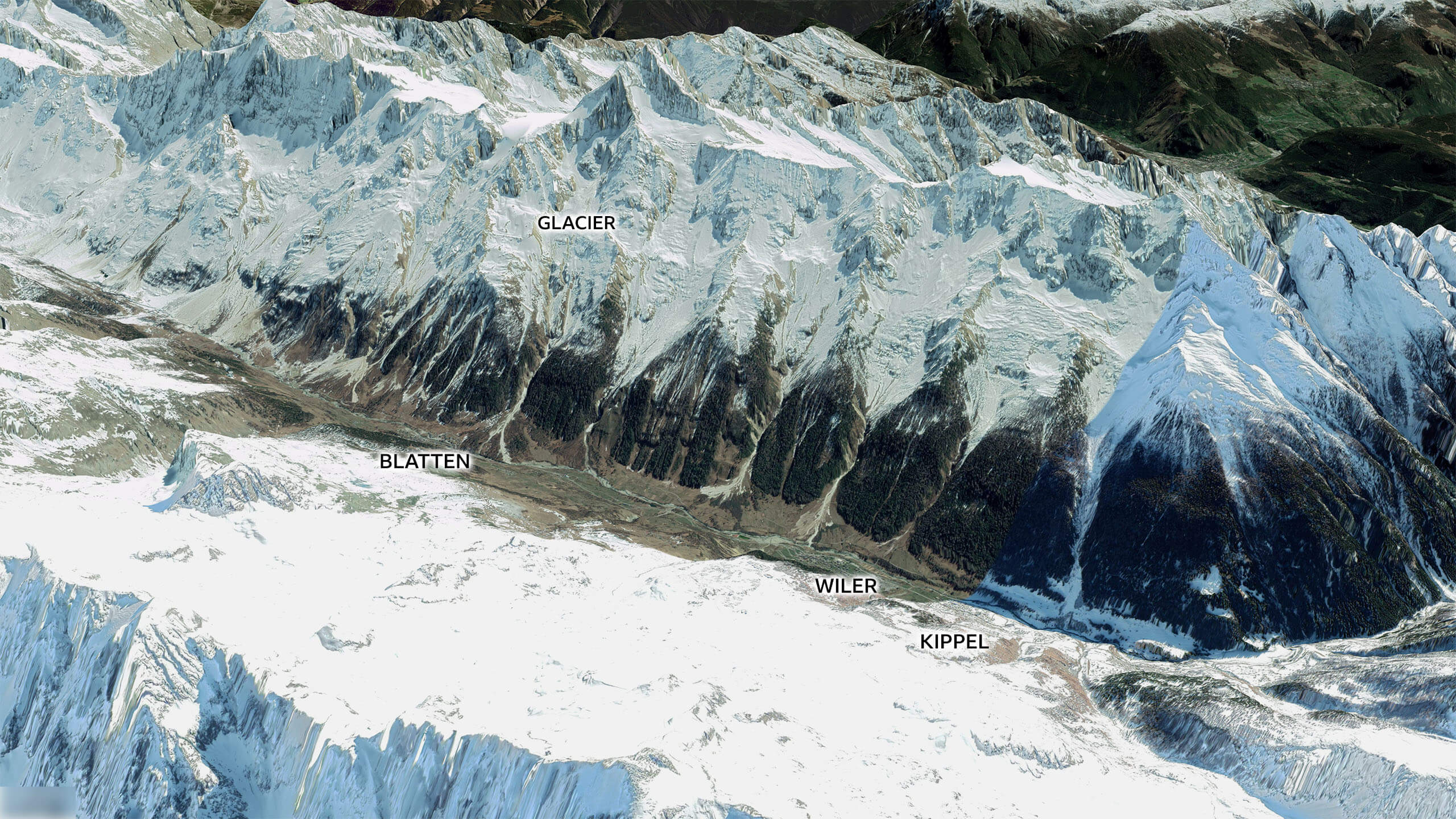

Kippel is over 4 km (2.5 miles) from Blatten. It and the entire valley were soon cloaked in dust. Blatten itself was completely destroyed; its homes, its church, its cosy Edelweiss hotel smashed to rubble.

Geologists had been monitoring the situation; that’s why Blatten was evacuated. But no-one, not even the experts, expected such huge violence.

“I was speechless,” said Matthias Huss, a leading glacier specialist at Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology. “It was the worst case that could happen.” Mr Huss had been aware of the situation in Blatten; he and his team check Switzerland’s glaciers all year round, and their annual reports show a clear, accelerated thaw, linked to global warming.

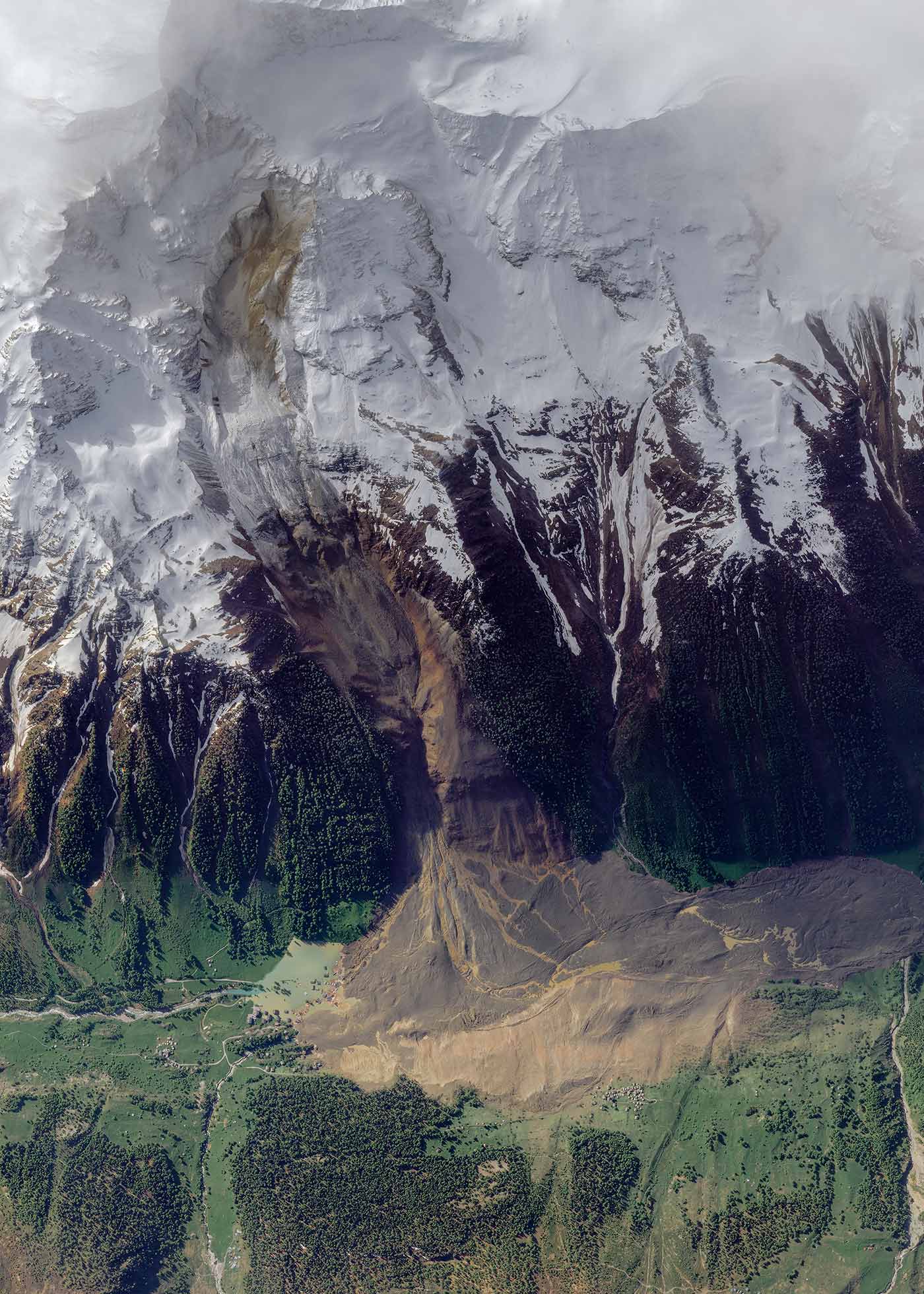

Blatten is now buried in rock and mud, and the clean-up operation is on hold because the tonnes of debris have blocked the River Lonza, causing a flood risk. So it is too soon to do a complete analysis of how exactly this disaster happened. But Matthias Huss points out that while Blatten may be the biggest, most dramatic alpine disaster in recent years, it isn’t the only one.

“We are seeing many,” he said, “and lots of these events in the last years in the Alps are linked to global warming. “There seems to be a link that's quite clear because the warming is affecting permafrost thaw and the permafrost is what stabilises these high mountains.”

Permafrost is often called the glue that holds the mountains together. When it thaws, the mountains crumble, and they start to break apart. At the same time, the glaciers are shrinking and, as they do, they uncover mountainsides that are unstable without their thick coat of ice.

These hazards are not entirely new. Glaciers do grow, retreat, and then grow again over centuries.

Seasonal avalanches and landslides tend to have their regular paths down the mountains. Alpine communities are used to this, and Switzerland has been extensively risk-mapped. One of the reasons villages like Blatten are where they are is precisely because they are not seen to be in the path of danger.

But over the last 20 years there has been a fundamental change. The glaciers, and the permafrost, are melting faster than ever.

The volume of ice is less than half what it was a century ago, and some glaciers have disappeared altogether, prompting alpine communities to hold funerals for them.

If global warming does not stay within the 1.5C rise agreed in the Paris climate accord, glaciologists believe most of Switzerland’s glaciers will be gone by the end of this century.

Until now the big worry has been the loss of a key, fresh water supply. Glaciers, often called the water towers of Europe, store the snow in winter, and release it gradually over the summer, filling rivers, and irrigating crops.

But Blatten has sounded new alarm bells. Despite all the monitoring and risk-mapping, the rapid thaw is making it very hard to accurately predict the danger.

Blatten’s residents were evacuated, but it was thought of as a precautionary measure, while the unstable rock and ice came down gradually. The authorities didn’t want anyone to get hurt.

Although one man aged 64 is missing, the evacuation saved hundreds of lives. But Blatten’s people lost everything else. Barely a house has been left standing, everything is buried under tonnes of rock and mud. Mr Huss fears that Blatten may be a sign of things to come.

“It really puts a question mark on living in the high mountains,” he says. “And I wouldn't exclude that in the future also other villages are going to be destroyed.”

One day after the tragedy in Blatten, locals gathered at the church in the neighbouring village of Wiler to mark Ascension Day.

Prayers were said for those who had lost their homes, and for the future of the community. “We all know each other around here,” said one woman. “Our valleys are small, that brings us closer together. There is real compassion.”

Others though voiced the fear that has spread right across the country. “It's terrible. They've lost everything. There's nothing we can do,” said another woman. “We can cry, but we cannot cry forever,” added an elderly man. “We must believe in God, that He will help us, so that life can go on.”

Or, as Matthias Huss put it, “This is really an event that will be quite decisive for Switzerland, and how we perceive the mountains.”

Credits

Produced by Dominic Bailey, Mike Hills and Tom Finn. Design by David Blood and Jake Friend. Development by Dan Smith, Giacomo Boscaini-Gilroy and Preeti Vaghela.