As Israeli bombs were toppling one high-rise building after another in Gaza City, a call came through that Gaza’s top archaeologist, Fadel al-Otol, had long dreaded. The Israeli military was warning it was about to attack a tower storing thousands of ancient treasures.

“Honestly, I can hardly speak, for two days I’ve barely slept,” Fadel told me on Friday from Switzerland, where he now lives with most of his family. “I’ve been extremely worried. I’ve felt as if a missile could strike at my heart at any moment.”

After international experts pressed Israel to give an extra day for the evacuation, Fadel and others remotely guided Palestinian volunteers and aid workers through an incredible feat. Racing against the clock, they moved away six lorryloads of artefacts – including fragile ceramics, mosaics and centuries-old skeletons – to a safer place across the bombed-out city.

Some items had previously been damaged by nearby Israeli shelling and break-ins at the site, but Fadel had left boxes of artefacts carefully packed and inventoried on the shelves.

He estimates that 70% of the contents of the ground-floor storeroom were successfully removed. They included many rare finds.

But all items left behind were crushed when rockets destroyed the 13-storey al-Kawthar building on Sunday. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) said it was targeting “Hamas terrorist infrastructure.”

It has since said its troops are moving towards the centre of Gaza City, starting the main phase of its operation to occupy the city fully.

“I am so sad. My heart is breaking,” Fadel wrote in his latest message. "It never once crossed my mind that archaeological sites, museums and stores would be destroyed one day."

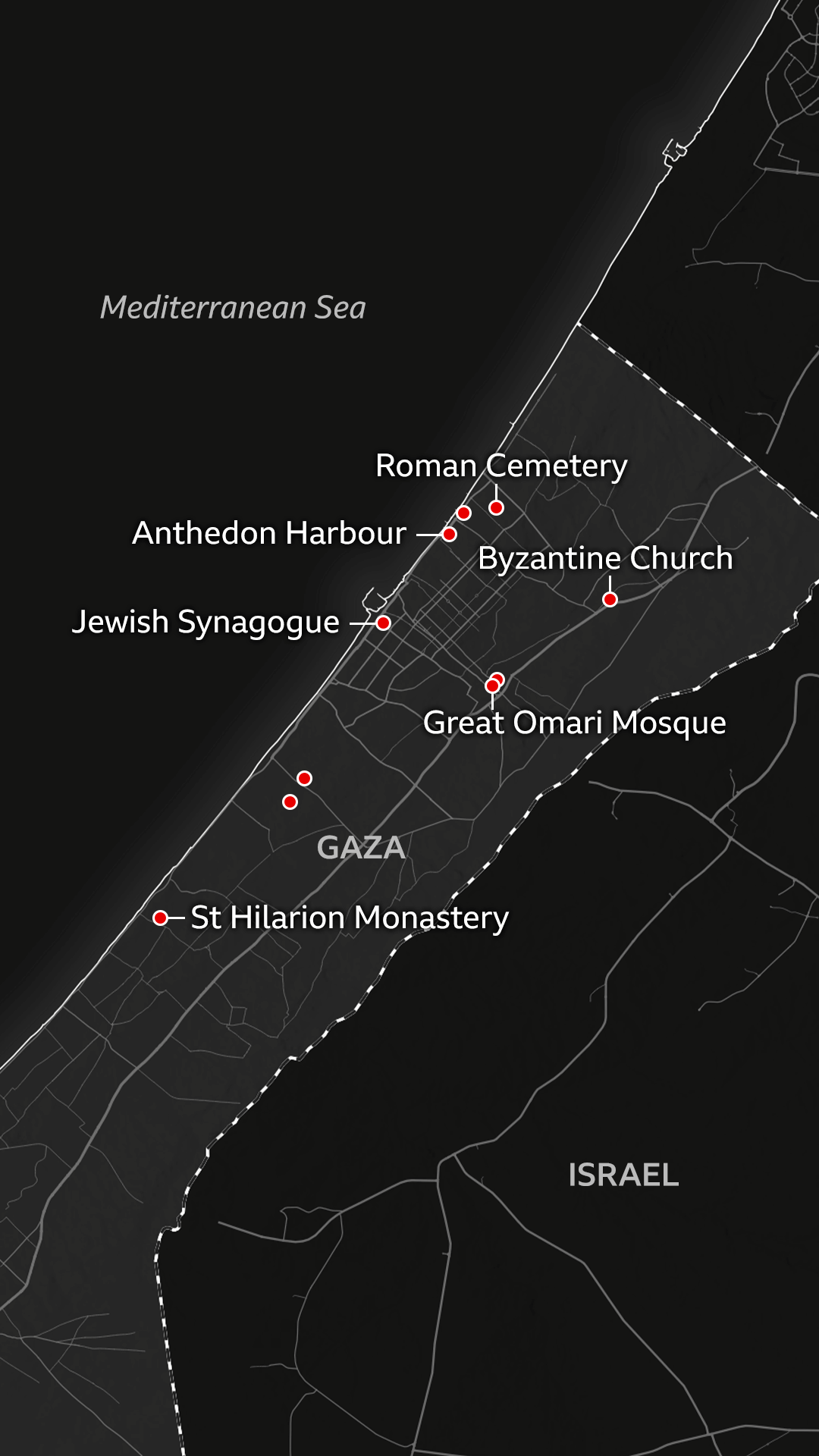

The history of the Gaza Strip dates back more than 5,000 years. In antiquity, it was a key port on the Mediterranean coast – on a busy trade route between Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia. In 332 BC, Alexander the Great besieged Gaza. In 1799, Napoleon stayed here.

The tiny territory, as we know it today, has seen different civilisations including Canaanites, Egyptians, Philistines, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Jewish Hasmoneans, Romans, Christian Byzantines and Muslim Mamluks and Ottomans. All have left their mark.

This vibrant cultural heritage is seen by many Palestinians as central to their identity. Despite the suffering of nearly two years of war, some have remained dedicated to saving Gaza’s past.

Fadel al-Otol had humble beginnings in one of Gaza's big urban refugee camps, Shati [Beach] camp. As a boy he was fascinated by the finds that would wash up along the coast in winter storms. "It all happened by coincidence," Fadel says, looking back on his career. "It turns out I was living next to the site of the ancient port of Anthedon."

During the 1990s, in his teens, Fadel followed a team from the French Biblical and Archaeological School in Jerusalem as it carried out excavations at Anthedon, which dates back nearly 3,000 years.

He ended up training in France before returning home to lead important digs including at St Hilarion, a vast early monastery in central Gaza, which was recognised as a Unesco World Heritage site last year.

“I loved working there so much,” Fadel says. “It reflects Gaza's rich history and social tolerance. The site was built in the 4th Century and continued to thrive until the 7th Century. During the Islamic Umayyad period, Muslims and Christians lived there."

For years, Fadel safeguarded the store kept in Gaza City by the French school. It included major finds from nearly three decades of local excavations. In recent times, there had been exciting discoveries at the Church of Al-Bureij in central Gaza and the largest Roman cemetery found in Gaza, Ard al-Moharbeen.

Everything changed on 7 October 2023, when Hamas fighters from Gaza led a cross-border attack on Israel, killing some 1,200 people. Hamas took 251 hostages, of whom 48 are still being held in Gaza, though only 20 are believed to still be alive.

“I loved working there so much,” Fadel says. “It reflects Gaza's rich history and social tolerance. The site was built in the 4th Century and continued to thrive until the 7th Century. During the Islamic Umayyad period, Muslims and Christians lived there."

For years, Fadel safeguarded the store kept in Gaza City by the French school. It included major finds from nearly three decades of local excavations. In recent times, there had been exciting discoveries at the Church of Al-Bureij in central Gaza and the largest Roman cemetery found in Gaza, Ard al-Moharbeen.

Everything changed on 7 October 2023, when Hamas fighters from Gaza led a cross-border attack on Israel, killing some 1,200 people. Hamas took 251 hostages, of whom 48 are still being held in Gaza, though only 20 are believed to still be alive.

In response, Israel launched a massive bombardment and ground invasion. According to the Hamas-run health ministry, close to 65,000 Palestinians have since been killed. There has been widespread destruction.

During the war, Unesco says it has verified damage to 110 sites of religious, historical and cultural importance.

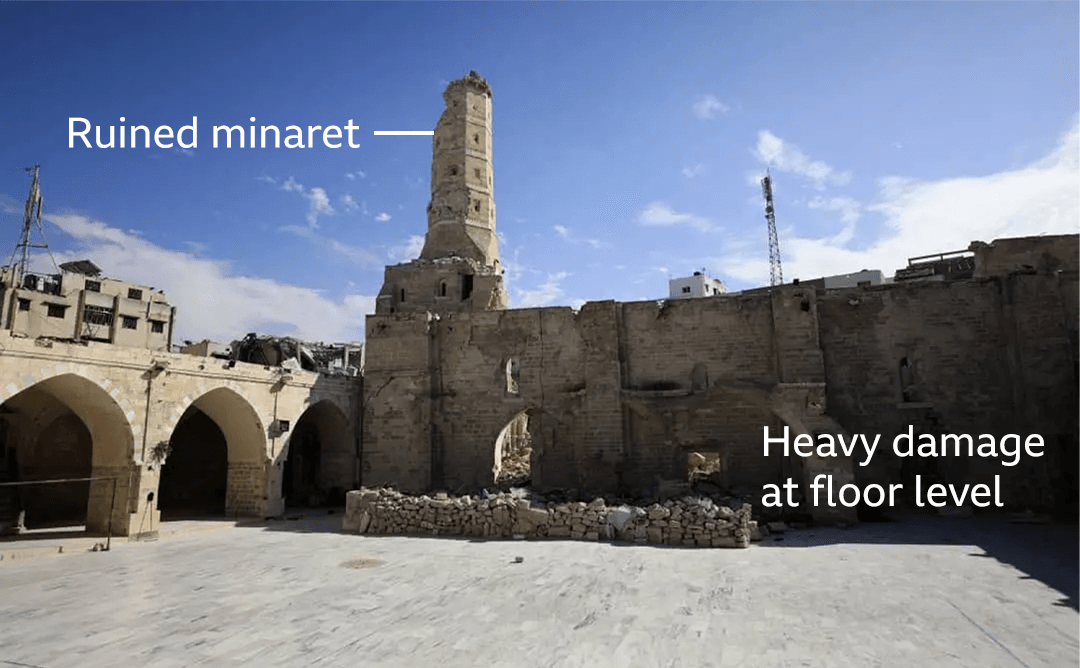

In Gaza City's Old Quarter, the distinctive octagonal minaret of the iconic Great Omari Mosque – the largest and oldest mosque in the Strip – has been left as a broken stump. The IDF says it hit "a tunnel shaft and terror tunnel”.

Nearby, the 700-year-old Qasr al-Basha, one of the jewels of Gaza, has been struck and bulldozed. In recent years it was used as a museum, and it is not known what happened to thousands of artefacts it contained. The IDF tells me it has no information about the targeting of the site.

The entrance to the medieval gold market, Souq al-Qissariya, took a direct hit – with the IDF saying it struck "a military target", and the restored Hammam al-Samra traditional bathhouse is no more.

Further north, Ard al-Moharbeen has been damaged and bulldozed. The IDF says it targeted "a Hamas military compound used for operational purposes".

The last time it was safe for experts to visit the 5th Century Byzantine church in Jabalia, they saw that a shelter built to protect its beautiful mosaics had collapsed onto them.

"The situation in Gaza is so difficult. People are just searching for something to eat and drink," observes Fadel, whose oldest daughter and two young grandchildren remain in the strip.

However, he says locals care deeply about all their losses. "Every day, I receive dozens of calls from friends, ordinary people and neighbours to express their sorrow because they are so connected with these ancient sites. I tell them once the war is over, we will restore these sites and artefacts."

Being an archaeologist in Gaza was never easy. Hamas – seen by many countries as a terrorist group – took over the strip by force in 2007, a year after it won Palestinian elections. Israel and Egypt then kept it under a tight blockade, saying this was to stop money and weapons reaching Hamas.

At times, Hamas celebrated finds from the ancient past. But it also built housing projects and military camps on archaeological sites – including Anthedon, Tel es-Sakan, a rare 4,500-year-old Bronze Age settlement and a 6th Century synagogue in Gaza City.

With little open space, a fast-growing population and a shattered economy, history was a low priority. Fadel tried every avenue to get support for local archaeology and found an ally in a French Palestinian from Gaza City, Jehad Abu Hassan.

Jehad works for the French humanitarian organisation Première Urgence Internationale, and set up a programme called Intiqal, training young Gazans to work on excavations and public tours. It is supported by the British Council - the UK's cultural and educational organisation - and the French development agency, AFD.

At a time when over 70% of new graduates were unemployed, Jehad saw that Intiqal had a real impact.

"We received a lot of applications and requests to do voluntary work so we feel that the local community started to see the importance of cultural heritage, where they can do something in this field," he recalls.

With little open space, a fast-growing population and a shattered economy, history was a low priority. Fadel tried every avenue to get support for local archaeology and found an ally in a French Palestinian from Gaza City, Jehad Abu Hassan.

Jehad works for the French humanitarian organisation, Première Urgence Internationale, and set up a programme called Intiqal, training young Gazans to work on excavations and public tours. It is supported by the British Council - the UK's cultural and educational organisation - and the French development agency, AFD.

At a time when over 70% of new graduates were unemployed, Jehad saw that Intiqal had a real impact.

"We received a lot of applications and requests to do voluntary work so we feel that the local community started to see the importance of cultural heritage, where they can do something in this field," he recalls.

In recent days, the Intiqal team worked with volunteers from the Holy Family Church to save the contents of the Gaza City archaeological store. It had previously placed security guards at the site and carried out regular checks after the IDF broke into it in early 2024, after which desperate Palestinians stripped it of shelves and boxes for firewood.

Right now, Jehad Abu Hassan says survival is the main priority for Gazans, but he believes cultural heritage could ultimately be a key part of a post-war plan. "You'd have to restart from almost zero, to build again and say to the world that Gaza is not only the images of violence and despair," he says, "but we have culture, we have history, we have people on this land."

In the past two years, top international courts have opened cases into alleged war crimes committed by Hamas and Israel, which deny the charges. Wiping out the cultural heritage of a people is part of an ongoing lawsuit at the International Court of Justice, where South Africa has accused Israel of genocide; a case that Israel said it rejected "with disgust."

The 1954 Hague Convention, to which Palestinians and Israelis are signatories, is supposed to safeguard cultural landmarks from the ravages of war. There is recognition that monuments, archaeological sites and museums are all part of people's history – the religious and ethnic threads which connect them to a place and make up their identity.

Israel blames Hamas for the destruction of important historic sites. The Israeli military tells me "Hamas deliberately embeds its military assets within densely populated civilian areas – Hamas acted and continues to act in the vicinity of, or beneath, cultural heritage sites."

"The IDF does not seek to cause excessive damage to civilian infrastructure and conducts strikes solely based on military necessity. In accordance with international law, careful consideration is given to the presence of sensitive sites," a statement says.

"This awareness is a central component in the planning of operational activity, and every effort is made to minimise harm to civilian infrastructure and non-involved civilians. Strikes involving potential risk to sensitive structures undergo a rigorous and multi-layered approval process."

A twist of fate has preserved another collection of impressive treasures from Gaza’s past. A selection is currently on show at the Institute of the Arab World in Paris and is being used to tell the territory's little-known history, as an oasis, open to the world, at a crossroads of civilisations.

"With what's happened, they have a new emotional impact," says the curator, Elodie Bouffard, when I visit.

There is an abundance of vases, statues, columns and tiny lamps. The centrepiece of the exhibition is a huge 6th Century mosaic from a church, decorated with animals and a grapevine, found by workers digging a road in Deir al-Balah.

Many of the items on display were originally sent to Geneva's Art and History Museum about two decades ago for an exhibition organised by the internationally backed Palestinian Authority. It was meant to fund a new museum in Gaza. After Hamas seized power, and Gaza's borders were sealed, the artefacts got stuck and were kept in storage.

A wealthy Gazan businessman, Jawdat Khoudary, had donated many of the pieces. He reluctantly left his home for Egypt early in the war with his family and spoke to me from a café in Cairo.

A property developer, he explains how his wide-ranging collection came from his workers' finds on building sites and pieces caught in the nets of fishermen, including an exquisite small statue of the Greek goddess Aphrodite now on display in Paris.

"I know all the operators of shovels who excavate, so I convinced them, if you find a piece of marble or pottery, don't destroy it, keep it in a good condition and give it to me and I will give you an allowance," Jawdat says. "They thought that I am a little bit crazy looking for pottery and stones, but day by day we convinced them that it's our history."

Like everyone in Gaza, Jawdat is mourning lost loved ones in the war, but he is heartbroken too by the loss of historic jewellery, coins, Palestinian costumes and artefacts he had gathered over decades. He had put some precious items in safe boxes in the bank, but many were on display in his al-Mathaf (The Museum) guesthouse in Gaza City.

Last year, Israeli forces struck the bank, the IDF says as part of its attacks on Hamas, as well as Jawdat's house and museum. The Israeli military says it targeted the latter because a senior operative from Hamas's Shati Camp battalion was staying there.

"I faced the reality that what I did in my life was destroyed in two hours," Jawdat says miserably. His company's remaining workers in Gaza have helped him retrieve some artefacts but a video he was sent shows that his museum was badly burned.

Much of what is gone is irreplaceable, Jawdat says. "If they destroy my factory, it's not a big issue, I can import new machines and rebuild again," he tells me. "But how shall I find amphora or Gaza coins again? How can I find it? That's the problem. The history of Gaza is hard to rebuild."

Back in Paris, there is a long queue for the Gaza exhibition. All the pieces on display are presented on trolleys – representing the goal to send them on to other international shows, but ultimately back to Gaza.

Meanwhile in Geneva, Fadel al-Otol - who has been working at the Art and History Museum since April – has been tasked with cataloguing, researching and preserving a total of about 500 items from Gaza which are still being kept there. Looking at all the collection he says evokes "sadness and nostalgia."

"However, I say, "thank God that these archaeological pieces are present here and not in Gaza," he adds. "Heaven forbid they could have been destroyed like all the others."

Additional reporting: Alex Last and Wael Hussein

Visual credits

BBC, Reuters, Getty Images, AFP, Fadel al-Otol, PUI