Uber Files: Greyballing, kill switches, lobbying - Uber's dark tricks revealed

In just over a decade, Uber has revolutionised how we move around our cities. The ride-hailing app was a game-changer: you just tapped your phone and a cab would find you. You even paid through the app.

The Californian tech company helped define the gig economy, where workers were seen as self-employed. Uber now has millions of drivers all over the world, and takes billions of pounds in fares.

Uber often described the regulated taxi industry it was trying to break into as a “cartel”.

But the company has been rocked by scandals. Uber drivers are fighting for their rights. And now a whistleblower has revealed the dark tricks Uber used to break into lucrative European markets.

Mark MacGann used to be one of Uber’s top executives. He was the company’s chief lobbyist, meeting senior members of government and heads of state in over 40 countries.

“People were almost falling over themselves in order to meet with Uber and to hear what we had to offer,” MacGann told the Guardian in an exclusive interview (see video below).

“It was extraordinarily easy to get access to the highest echelons of power and decision-making. It was intoxicating.”

Now he’s turned whistleblower.

Thousands of documents were leaked to the Guardian, who shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and media partners around the world, including the BBC.

The Uber Files are an unprecedented insight into how one of the world’s most notorious tech companies lobbied at the highest level to assist its aggressive expansion into Europe.

Uber raised billions in investment, using funds to attract drivers and passengers and challenge the rules. But Uber needed political support to disrupt the taxi industry.

The leak reveals how undeclared meetings, high-level lobbying, and backroom deals helped Uber to get leading politicians to back their radical plans. The leaked documents cover the years Uber was trying to break into Europe and they show how much Uber was prepared to spend to get close to power. In 2016, its lobbying and public relations budget was $90 million (£75 million).

Part 1: Paris

The taxi wars

Paris was the first European city where Uber launched. It’s also where co-founders Travis Kalanick and Garrett Camp first had the idea for the app, when they could not find a cab on a freezing cold night.

Paris had a strong network of licensed city taxis with the monopoly on picking up roadside passengers around town. Uber’s arrival caused chaos.

Uber billed itself as a tech firm that connected passengers with private-hire cars - minicabs - which had to be pre-booked. Except that its drivers could be summoned within a few minutes at the click of a button, right from the side of the road. What’s more, Uber’s prices were cut-throat - and there was no need to keep cash on hand.

The Parisian cab drivers were losing customers and income – and in 2014 took their protest to the streets. Taxi drivers attacked Ubers carrying terrified passengers, smashing their windows and slashing their tyres.

But Uber had a mantra, says MacGann: “It’s better to ask for forgiveness than to ask for permission”. Rather than bow to pressure, Uber pushed harder.

In February 2014 it launched a controversial new service called UberPop - called a “ride-sharing” service, it was the cheapest option on the app and like offering someone a lift.

UberPop drivers didn’t need to have a professional license or be insured as a taxi driver. It meant practically anyone with a car could become a cabbie, and many jumped at the chance.

At a stroke, taxi drivers had lost their advantage.

Uber immediately ran foul of the authorities, landing a €100,000 fine for misleadingly advertising the new service as a car pool. New legislation was being debated that would impose strict regulations on UberPop and similar ride-sharing services.

But Uber had also begun to make friends with a young politician in his first ministerial post: Emmanuel Macron.

In 2014, Macron was minister for the economy and digital affairs, and a rising star. He had come into government with the aim of shaking things up and wanted to address unemployment by liberalising traditional labour structures. Uber fitted this model perfectly.

The leaked documents reveal that company executives, including MacGann and Uber’s CEO at the time, Travis Kalanick, attended a series of meetings with Macron. Only one of these was made public before now.

Uber thought the first meeting with Macron on 1 October 2014 was “spectacular. Like I’ve never seen”. The firm believed it had found a strong political champion.

The leaked documents also contain dozens of personal messages and emails between Uber and its powerful new friend. Their communications were amicable, and at times casual.

Emmanuel,

[...] I was encouraged by your supportive comments at LeWev [sic] [...]

We continue to be committed to France and a positive transformation in the transportation sector and I’d love to have a quick chat with you, or to set up a meeting to discuss how we can continue to make progress in light of recent comments by government officials. [...]

Let me know if there is a time that makes sense to connect. Looking forward to chatting soon.

Travis

Yes dear Travis, would be happy to chat with you. Let us schedule that !

Best,

Emmanuel

Uber even sent Macron proposals for how it wanted ride-sharing services regulated in France.

But having such a well-connected friend was not a perfect shield.

Socialist MP Thomas Thévenoud had been brought in to find common ground between taxis and ride-hailing platforms like Uber.

He describes the way Uber went about its business as “cowboy”. “They put one foot in the door, then break the door wide open and once they're in, you're forced to deal with them for better or for worse.”

From 1 January 2015, his new law made UberPop illegal. Uber carried on running the service as it challenged court rulings.

By the summer, tensions peaked. Taxi drivers went on general strike, with protests sometimes turning violent, while government ministers called for the end of UberPop and for unlicensed drivers’ cars to be seized.

Interior Minister Bernard Cazeneuve, who was in regular contact with the taxi unions, ordered tighter controls on UberPop drivers.

“The government will never accept the law of the jungle,” he said.

Macron maintained contact with Uber throughout, as the BBC has reported, and UberPop was suspended on 3 July.

Uber’s powerful friend became president in 2017, and under President Macron France has thousands more drivers.

A spokesperson for President Macron said that his ministerial job “led him to interact with many companies involved in the transformation of services”, which had to be facilitated by “removing administrative and regulatory barriers”.

“The point is that today the French government is probably the most pro-Uber government in the western world,” Mr Thévenoud told BBC Panorama.

But the years of taxi wars had also played into Uber’s narrative. In 2016, amidst more violent taxi demonstrations, the French government announced a clampdown on ride-sharing services.

In response, Travis Kalanick proposed a counter-protest. When an Uber executive flagged MacGann’s concern over the safety of Uber drivers and riders, Kalanick responded:

Kalanick “viewed violence as something that brought results”, says Mark MacGann. “It’s dangerous. It’s irresponsible. It’s also, in a way, very selfish. Because he was not the guy on the street who is being threatened, who is being attacked.”

A spokesperson for Travis Kalanick said he “never suggested that Uber should take advantage of violence at the expense of driver safety”.

That protest went ahead without incident, but this kind of exchange was not an isolated example. The leak suggests that exploiting violence against Uber drivers formed an important part of Uber’s communications strategy.

In an email from the Netherlands, Uber deliberately sought to “keep the violence narrative going for a few days” as it shared police reports of attacks against its drivers with Dutch media.

When those reports were published on the front page of Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf - without making Uber’s involvement clear - MacGann replied that this was “excellent work” and “exactly what we wanted”. Sharing the newspaper reports with other company executives, he added: "Step one in the campaign: get the media to talk about Taxi violence against POP [UberPop] drivers.”

Responding now to questions about his participation in Uber’s attempts to leverage violence against its drivers for strategic benefit, MacGann says: "There is no excuse for how the company played with people’s lives. I am disgusted and ashamed that I was a party to the trivialisation of such violence.”

Uber’s spokesperson Jill Hazelbaker says “there is much our former CEO said nearly a decade ago that we would certainly not condone today”. She adds nobody at the company had ever been happy about violence against drivers, and that the new management have “made safety one of the company’s top priorities”.

Part 2: Amsterdam

Duping the police

Fighting the law is part of the Uber spirit. The company has always seen itself as a “disruptor” – changing the world to suit its own interests. And lobbying wasn’t the only weapon in Uber’s arsenal.

Back in 2014, the controversial UberPop service was also attracting the attention of the authorities in Amsterdam, where Uber had its international headquarters.

When UberPop launched, the ILT, the body responsible for transport safety in the Netherlands, said that the moment it allowed the service to be used, Uber would be breaking the law.

There was initial concern among Uber’s top brass that the drivers of their ride-sharing platform would face criminal charges if arrested, according to leaked emails from a senior company executive.

We've had a chat about that with TK [Travis Kalanick] while he was in Europe and agreed the real concern was jail risk. There is technically a criminal risk in a number of POP countries right now.

But they did not consider it an imminent threat, and when the first arrests of UberPop drivers in Amsterdam merely resulted in formal warnings and a threat of a fine, Uber doubled down.

Interesting that the ILT is not taking an aggressive approach. That means we should continue to push POP full steam

In December 2014, UberPop was declared illegal by a court in The Hague.

But like in Paris, Uber wasn’t going to let that stop it. The documents reveal how Uber used its smartphone app to block law enforcement from getting to its drivers in the first place.

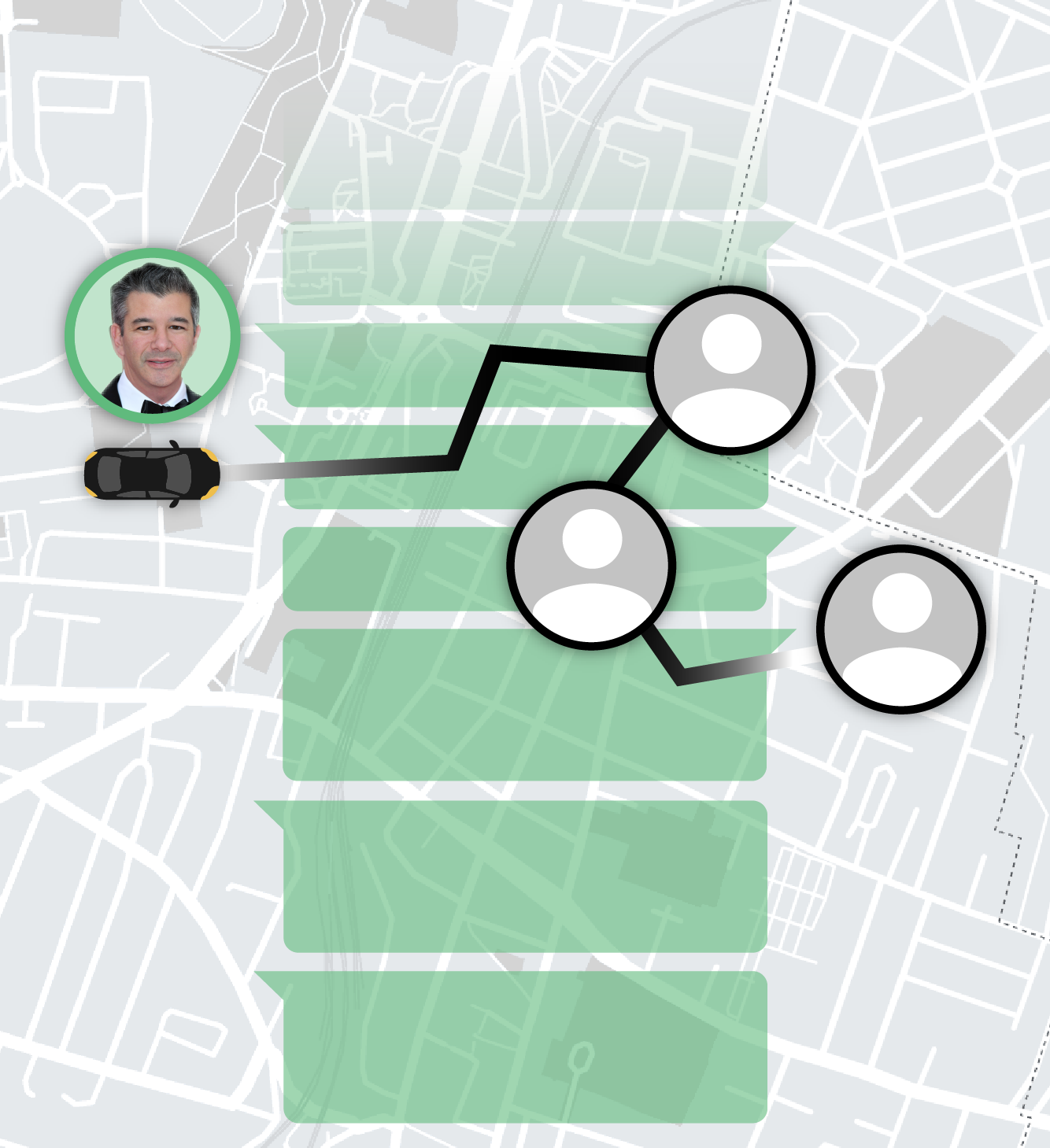

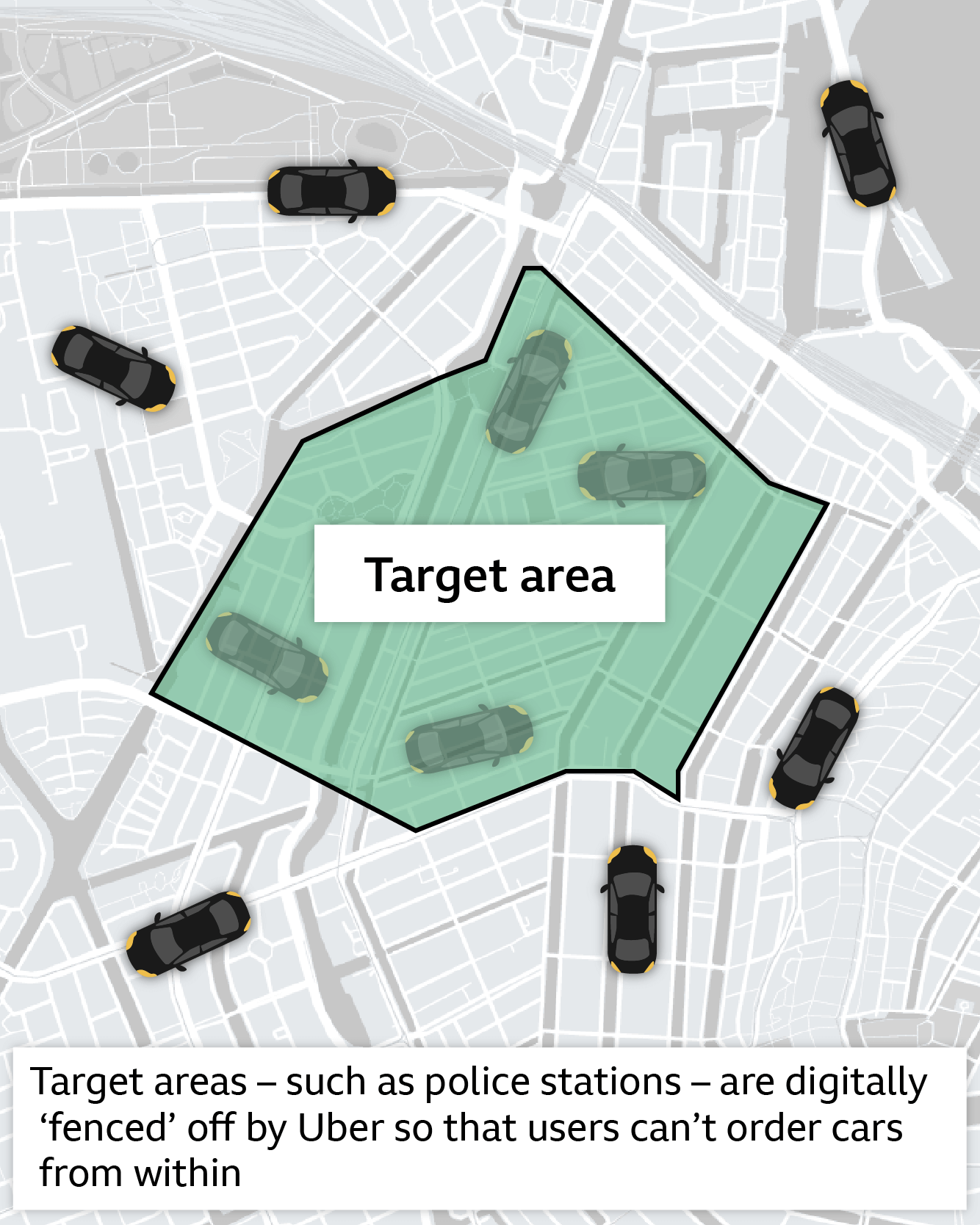

Uber identified police officers through data mined from the app and then, using an internal tool called “greyball”, served them a fake view of the UberPop app, populated with ghost cars that wouldn’t stop for them. They could also block anyone from booking in certain zones, like around police stations, using a tool called “geofencing”.

These tricks left law enforcement officials scratching their heads, struggling to understand why they could not book a ride.

Prof Bart Custers, a digital law expert at Leiden University in the Netherlands, says that collecting and processing personal data on law enforcement officers may have been illegal. “EU data protection law prescribed there should be a legal basis for this,” he says - which the company did not appear to have.

Uber says “we stopped using these tools in 2017 when Dara Khosrowshahi became CEO and, as we have said many times, they should never have been used”.

The cat-and-mouse game between Dutch law enforcement and Uber continued.

In March 2015 it came to a crunch when the police demanded a list of all UberPop drivers. Handing over such a document would have been hugely damaging to the firm, allowing police to arrest drivers without having to catch them in the act.

Internal emails reveal that the company did not plan on co-operating and, with the battle lines drawn, Uber expected that it would not take long before its Amsterdam headquarters were raided.

But Uber had a secret system to prevent the police from getting their hands on evidence: the “kill switch”. It could could lock down the company’s servers remotely, to make company information inaccessible.

The Uber Files reveal how its use was more widespread than previously known and an order to use it came directly from the top. On 2 April 2015, the day of another raid on Uber’s Amsterdam offices, the company’s then CEO Travis Kalanick emailed staff to hit the kill switch.

Please hit the kill switch ASAP - Access must be shut down in AMS.

And during a raid in Paris, executives described how the toughest part was keeping a straight face when they could not assist investigators.

Lawyer Brendan Newitt told Panorama that if the systems were shut down once the raid began, Uber could have been breaking Dutch law.

Again, Uber says such software should never have been used. It told the ICIJ that it now routinely co-operates with information requests and “does not have a ‘kill switch’ designed to thwart regulatory inquiries”.

Mark MacGann said that on every occasion he was “personally involved in ‘kill switch’ activities” he was “acting on the express orders” from management in San Francisco.

Kalanick’s spokesperson said he “never authorised any actions or programs that would obstruct justice in any country”, adding that Uber had “fail-safe protocols” to protect intellectual property which “do not delete any data” and were approved by Uber’s lawyers.

Of course in the Netherlands too, Uber had friends in high places. As the BBC has reported, it had an influential secret ally in Dutch politician Neelie Kroes, whose support may have been a breach of EU ethics rules.

And lobbying at the highest level would also be key to conquering another market: London.

Part 3: London

Unseating the black cabs

Travis Kalanick described London as “the Champions’ League of transportation” in a 2014 interview. “It has got a more dynamic, more competitive transportation system than any other city in the world.” Not to mention one of the most recognisable fleets of taxis: black cabs.

The company launched in London in summer of 2012, just in time for the Olympics.

Black cabs were the only ones allowed to be hailed from the street. Minicabs and Ubers both had to be pre-booked - but Uber’s app is so quick, it’s almost like hailing a cab from the side of the road.

For Uber drivers like Abdurzak Hadi, it was revolutionary. “You could drive and get a ping if someone needs to be picked up. We loved it.” The fares were lower than local minicabs and they got plenty of work.

The black cabs couldn’t compete with Uber’s low fares and went to war, bringing London to a standstill with a mass demonstration in 2014.

Once again, Uber began to look for friends in high places, starting with then-London Mayor, Boris Johnson. But Johnson repeatedly declined official meetings with Uber.

A leaked text message reports Johnson saying that it “would be less damaging politically to be photographed with the leader of ISIS than with Travis Kalanick”.

So the company went over his head.

The Mayor remains the central figure in London government [...] he is the ultimate target of engagement in London. Given these relationships, the need therefore is for a more positive image of Uber to be conveyed to Boris, by people that he trusts and respects.

The documents show Uber’s lobbyists were welcomed into 10 Downing Street, where they met senior advisers to the prime minister at the time, David Cameron, and recorded having a “useful conversation including intelligence on Mayor's office”.

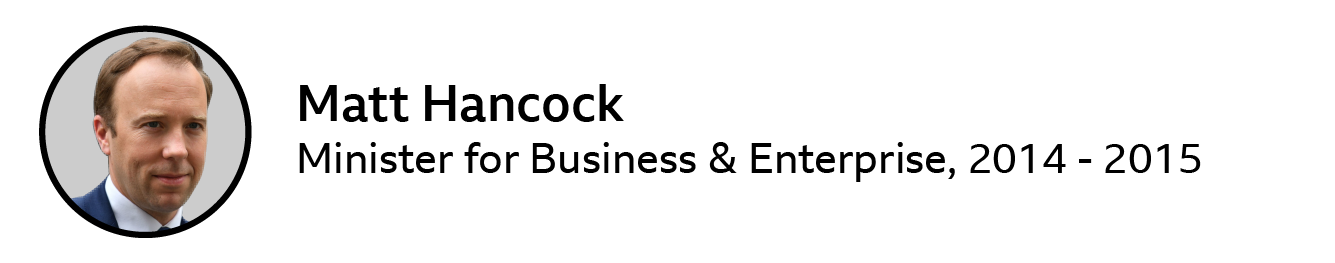

They also met two government ministers that day - Sajid Javid, then minister for culture, media and sport, and Matt Hancock, then minister for business and enterprise. But neither meeting was ever declared.

Hancock looked like he would be a natural ally, having tweeted during the taxi strike in June: “Does anyone have details of this #Uber app everyone's talking about? It sounds awesome…”

Uber kept a grid of meetings, and the files show the firm’s lobbyists managed to meet with him again over dinner, adding that he used an Uber car to get home from the event, a claim Mr Hancock denies.

Matt Hancock’s spokeperson said his first meeting in Downing Street was “for Number 10 officials to declare”, and the second was “a dinner about politics” that “was not declarable”.

A spokesperson for Mr Hancock said: "It was the policy of the Government - quite rightly - to attract tech companies to the UK. All the efforts Matt undertook in pursuit of that were above board and declared properly."

A spokesperson for Sajid Javid said that the “relevant departments hold no record of the meeting said to have taken place".

The lobbying went on and on. Uber targeted Tory, Lib Dem and Labour MPs. And after Number 10, it set its sights on the man next door.

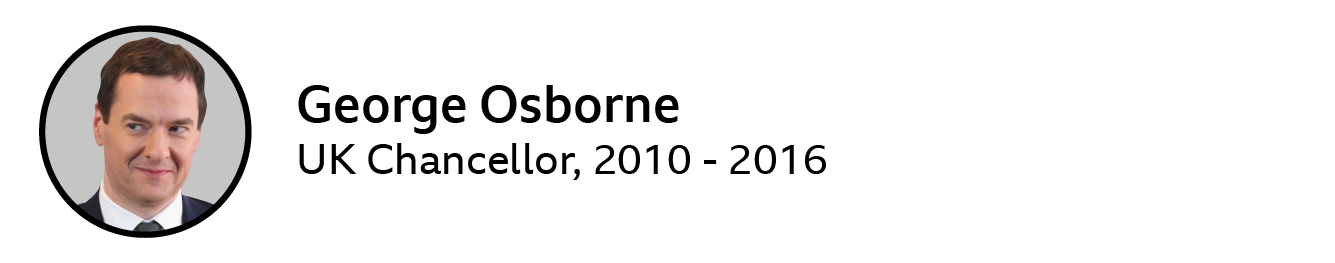

The documents show Kalanick was invited to a small dinner party with George Osborne, then chancellor of the exchequer, when he was visiting Silicon Valley.

Uber clearly saw the evening as a work event - and privacy was a selling point.

TK [Travis Kalanick], I think this is worth you doing. We were going to get you in front of Osborne when you're in London, but this is a much more private affair, no hanger-on officials or staffers. If you [...] are free the evening of the 25th, I think it would be a good use of your time. Let me know.

Osborne did not declare the dinner meeting.

“It perfectly encapsulates the problem with lobbying and how vested interests capture ministers and decision-making,” says lobbying expert Dr Susan Hawley, from Spotlight on Corruption.

“If anything of substance is discussed, ministers should be mindful to go back and report those conversations so the civil servants can decide: how do we make sure the public interest is properly protected?”

George Osborne’s spokesperson said that “far from being secret” it was the “publicly announced policy” to meet tech businesses and “persuade them to invest in Britain”.

“All business meetings... were properly declared,” he said.

Uber’s campaign seems to have worked though. Proposals that would have limited Uber’s expansion in London - such as a minimum five-minute wait between booking a ride and pick-up - were dropped.

According to the files, Uber executives later reported that Osborne considered himself "responsible" for the "positive" outcome. These revelations are likely to prompt renewed concerns that government ministers put pressure on Boris Johnson.

The documents also reveal that one minister was so impressed with Uber that they were open to further collaboration with the company.

Priti Patel, then minister of state for employment, followed up a conversation with another Uber lobbyist. Her letter is contained in the leak.

[...] I found our conversation fascinating and I was impressed by the number of jobs you have created in the UK alone.

[...]there is no doubt that we could forge an important partnership between Uber and my department. [...] I’d like to explore further how your flexible business model and our new approach to paying benefits could help get more unemployed people back into work. [...]

The meeting was not declared.

Patel’s spokesperson said, “For official meetings such as this, civil servants are present and responsible for making the appropriate recordings.”

The latest battle

The drivers

Travis Kalanick resigned in 2017 following a series of scandals at the company about sexual harassment, macho culture and the departure of senior executives.

Uber has now been under new management for five years and says its new chief executive has transformed the company. Uber says it’s “moved from an era of confrontation to one of collaboration”.

The company denies its lobbying was secret as it has always “expressed... policy positions vocally and publicly”. It says it has “admitted many mistakes and missteps” but that “engagements with governments” are now “both in line with the law and also transparent”.

Uber “will not make excuses for past behaviour” and asks “the public to judge us by what we’ve done over the last five years”.

Today, Uber is still embroiled in legal battles. The company has been challenged by its drivers in several countries over whether they should be classed as workers or self-employed. Where the courts ruled that Uber should treat its drivers like employees, the company has launched appeal after appeal.

In February 2021, ending a five-year legal battle, the UK’s Supreme Court ruled that Uber had to treat its drivers as workers rather than self-employed - which means they are entitled to the minimum wage, holiday pay and a pension.

But in the UK, drivers have also seen cuts to the amount of cash they get for each trip. Abdurzak Hadi is now a union leader, fighting Uber for better conditions. After eight years with the company, he says he’s had enough. “I think they see me as a robot. It makes you very angry. It's not a driverless car - there's a human being driving that's actually being exploited.”

In Amsterdam and elsewhere, Uber continues to challenge court rulings that drivers are employees entitled to greater workers' rights. In September last year, the company said it "has no plans to employ drivers in the Netherlands".

The man behind the leak, Mark MacGann, says he hopes there will be a change in how Uber treats its drivers, many of whom earn “vastly less than the minimum wage”.

MacGann left Uber in August 2016. He pursued legal action against the company, eventually reaching an out of court settlement. The terms were not disclosed and he provided no further details.

In an interview with the Guardian, he said he resigned as he feared for his and his family's safety, citing increasing harassment from the taxi industry in various countries.

He says he now regrets his role in building Uber.

“I own what I did, but if it turns out that what I was trying to persuade governments, ministers, prime ministers, presidents and drivers, turned out to be horribly, horribly wrong and untrue, then it’s incumbent upon me to go back and say, ‘I think we made a mistake.’”

The Uber Files is a leak of 124,000 records including emails and texts exposing conversations and meetings between Uber executives and public officials as the technology-driven taxi firm sought to expand its business. The files were leaked to the Guardian which shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists in Washington DC and media partners in 29 countries, including the BBC's Panorama.

You can watch Panorama: Taking us for a Ride: The Uber Files on on BBC iPlayer (UK only)

Update 14 July 2022: This article has been amended to include a statement regarding Matt Hancock and his denial that he took an Uber after the dinner mentioned.

Massive leak reveals how top politicians secretly helped Uber

Massive leak reveals how top politicians secretly helped Uber

Uber lobbied top ministers at undeclared meetings

Uber lobbied top ministers at undeclared meetings

Taking us for a Ride: The Uber Files

Taking us for a Ride: The Uber Files