The struggle for control of the Arctic is accelerating - and riskier than ever

Tensions are growing at the top of the world.

US President Donald Trump wants Greenland, Russia is modernising its Arctic military bases, Chinese icebreakers are opening new routes and spies are being unmasked.

But as the battle for one of the world’s coldest places heats up, an increasingly fragile security balance may be breaking down, leading to an escalating arms race.

‘Frontier for deterrence’

President Trump has repeatedly stated his desire to control Greenland.

“We need Greenland for national security purposes,” he has said. “I've been told that for a long time.”

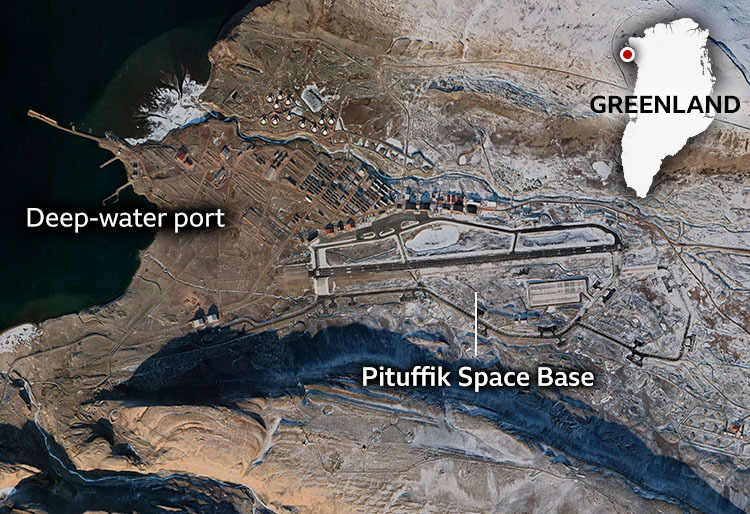

The question of why a territory with only 56,000 or so people matters comes down to geography.

In the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union, nuclear weapons were the ultimate instruments of war, holding the balance of terror. And the fastest route for weapons to reach their targets was over the North Pole.

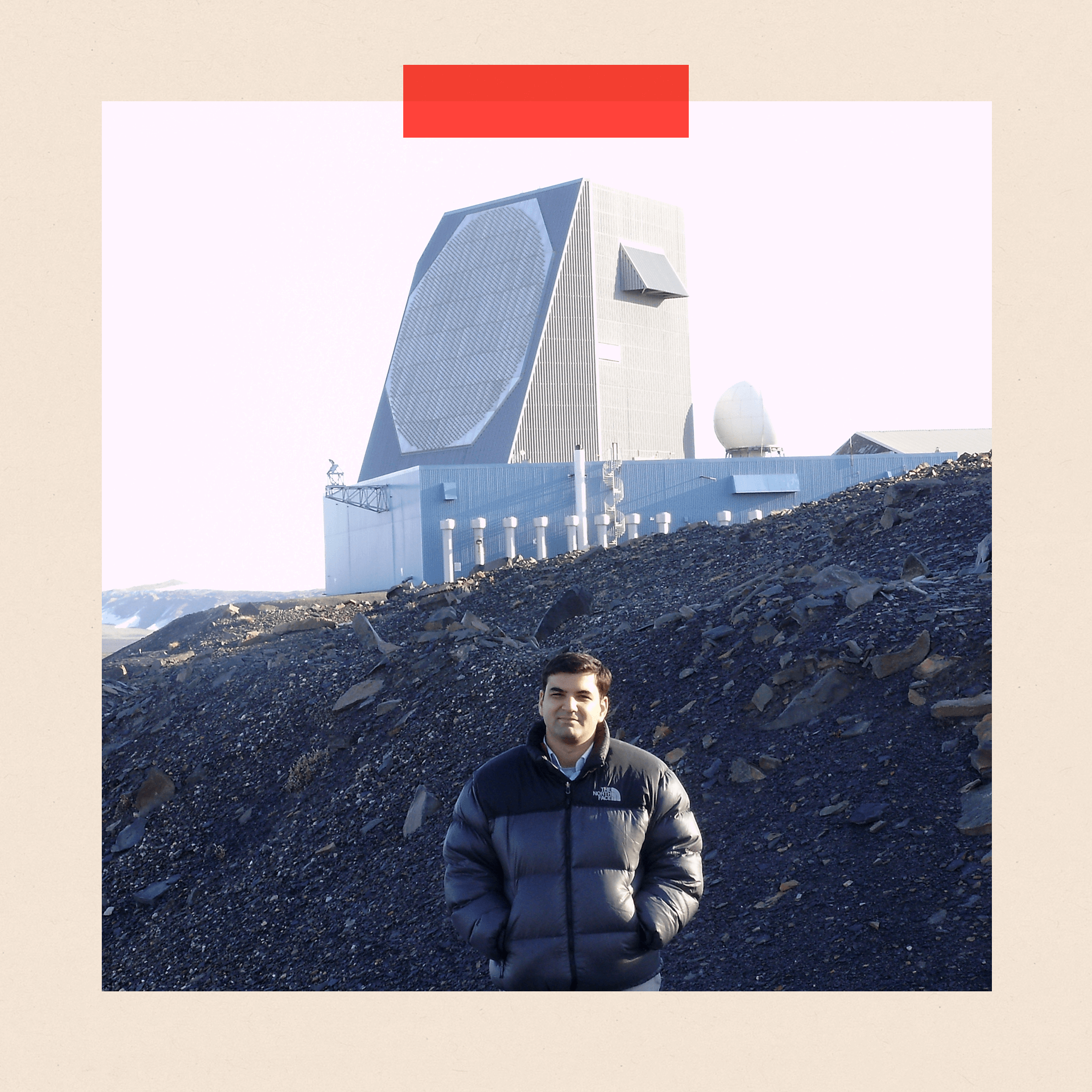

At the dawn of the Cold War, the US established an important base in the remote North of Greenland at a place called Thule - recently renamed Pituffik Space Base, which I visited in 2008.

At the base, a huge radar stands like a giant sentry, scanning the skies and space for anything coming over the top of the world. As I approached, the car engine began buzzing and the dashboard controls jumped wildly thanks to its emissions.

Inside the base, US military officers explained how the radar allowed them to see objects as small as a tennis ball as they moved through space.

The Cold War may be gone but the site’s importance has not diminished. It still forms a crucial part of BMEWS – America’s Ballistic Missile Early Warning System.

President Trump has talked about wanting a Golden Dome to protect the US, a reference to the Iron Dome that helps protect Israel from missiles. Early warning sites would be vital for such a system, with Greenland offering significant potential as a forward operating base for both defence and offense.

“Greenland is an enviable piece of real estate for Washington, it is basically physical insurance for the American homeland,” explains Dr Elizabeth Buchanan, a former Australian defence official and author of a forthcoming book on the territory. “It is no wonder it has always been viewed as a frontier for deterrence.”

That will worry Russia, which has long been nervous about US missile defence undermining its deterrence. But it is also alienating allies.

Greenland is still part of Denmark, where there has been anger over Washington’s acquisitive talk earlier this year. Many in Canada have also been profoundly shocked by talk of making it the 51st state of the US, something that Justin Trudeau, who was prime minister at the time, flatly ruled out.

Gaining more control of Greenland is a more likely ambition, and Europeans are quietly and privately worrying how Nato – an alliance designed to defend against Russia - could deal with a situation when its most powerful member, the US, wants to take territory from another member, Denmark.

‘Potential for escalation’ over the seas

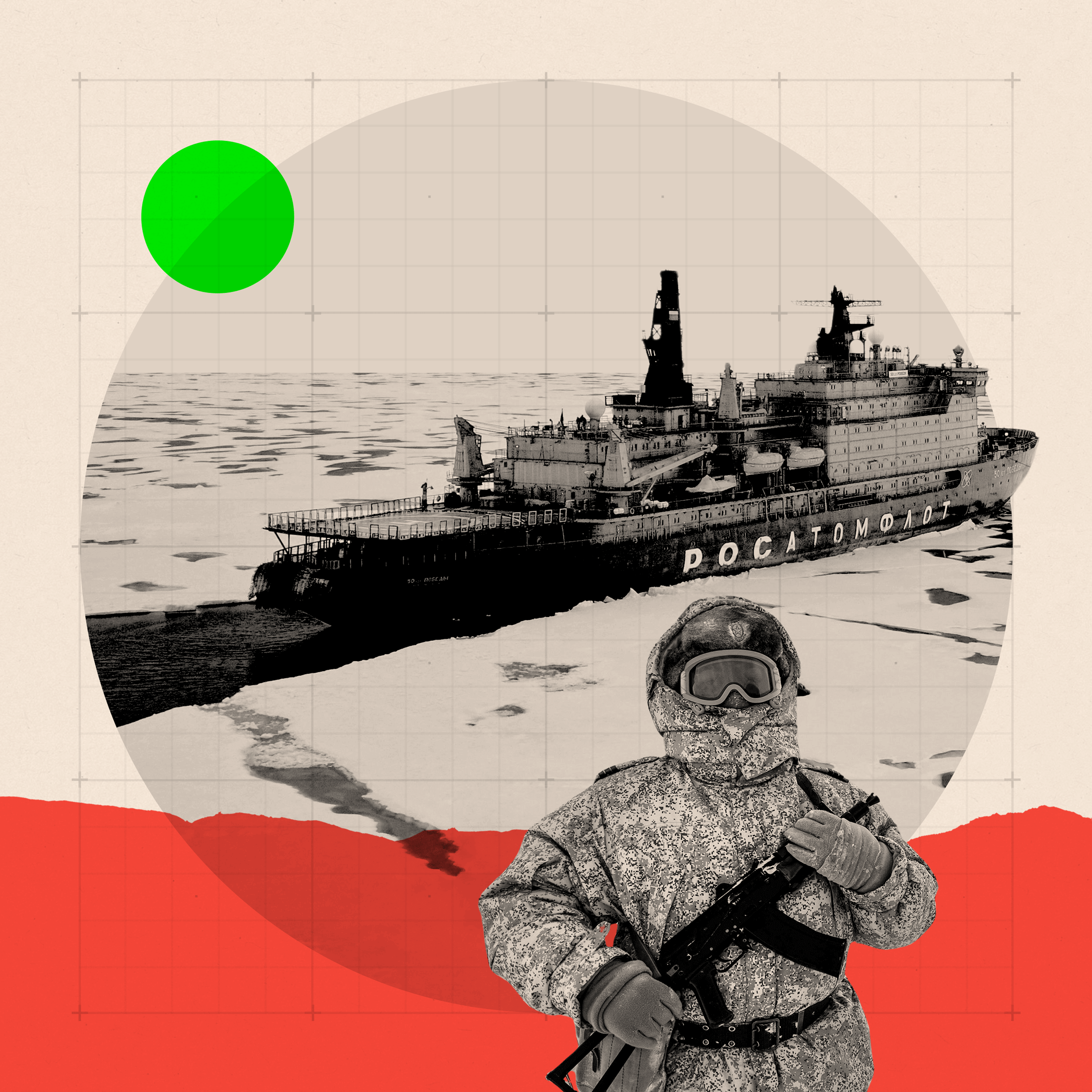

Russia is the most important player in the region. A fifth of its territory is in the Arctic and it accounts for more than half of the coastline.

It is the country that others worry most about when it comes to militarising the Arctic, but also the country with most to lose from such a development.

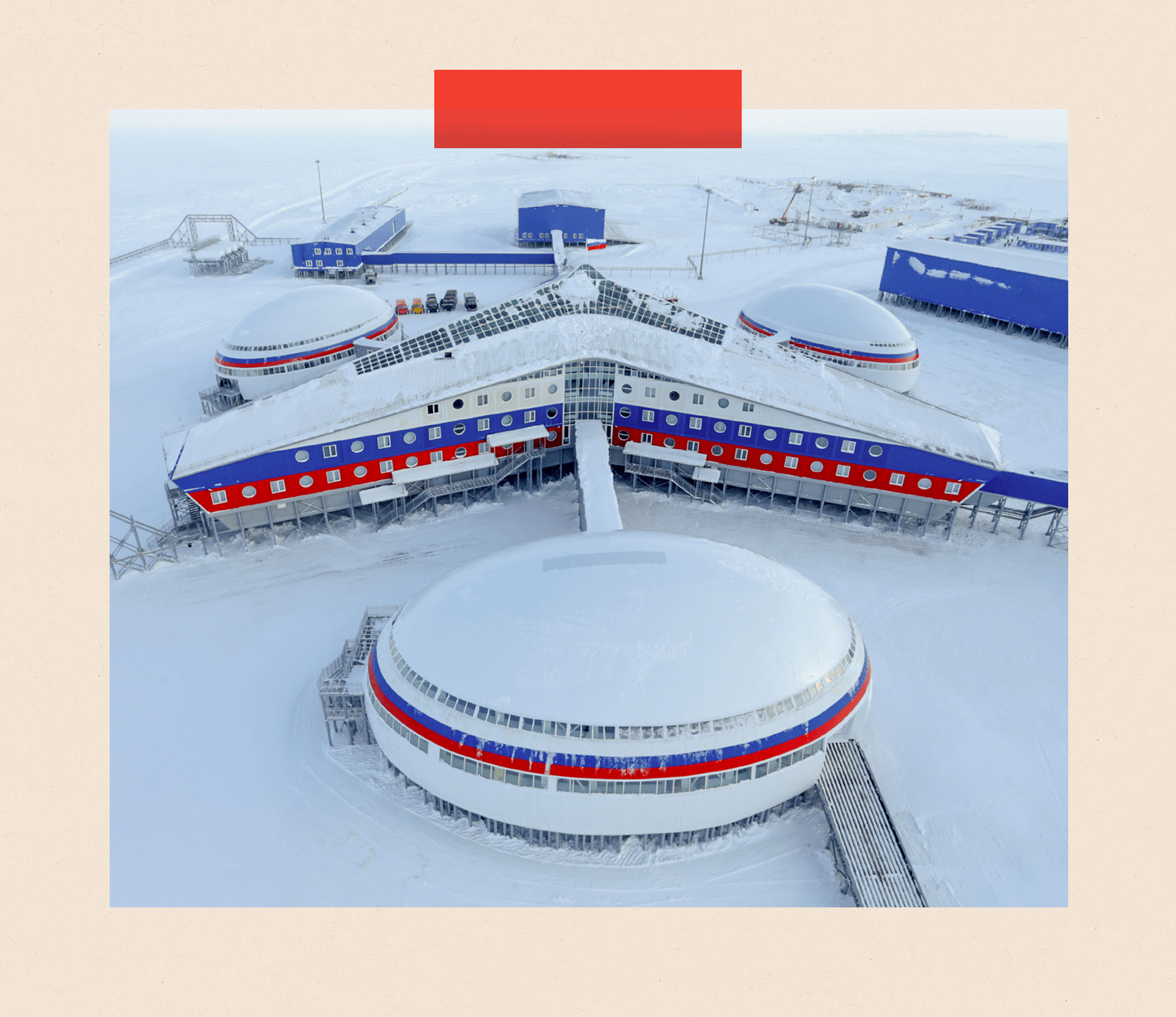

Where Western powers largely drew back from the region until recently, Russia has spent years investing in its presence, upgrading airbases like Nagurskoye, which has been in operation since the Cold War and can now handle large aircraft in the extreme North.

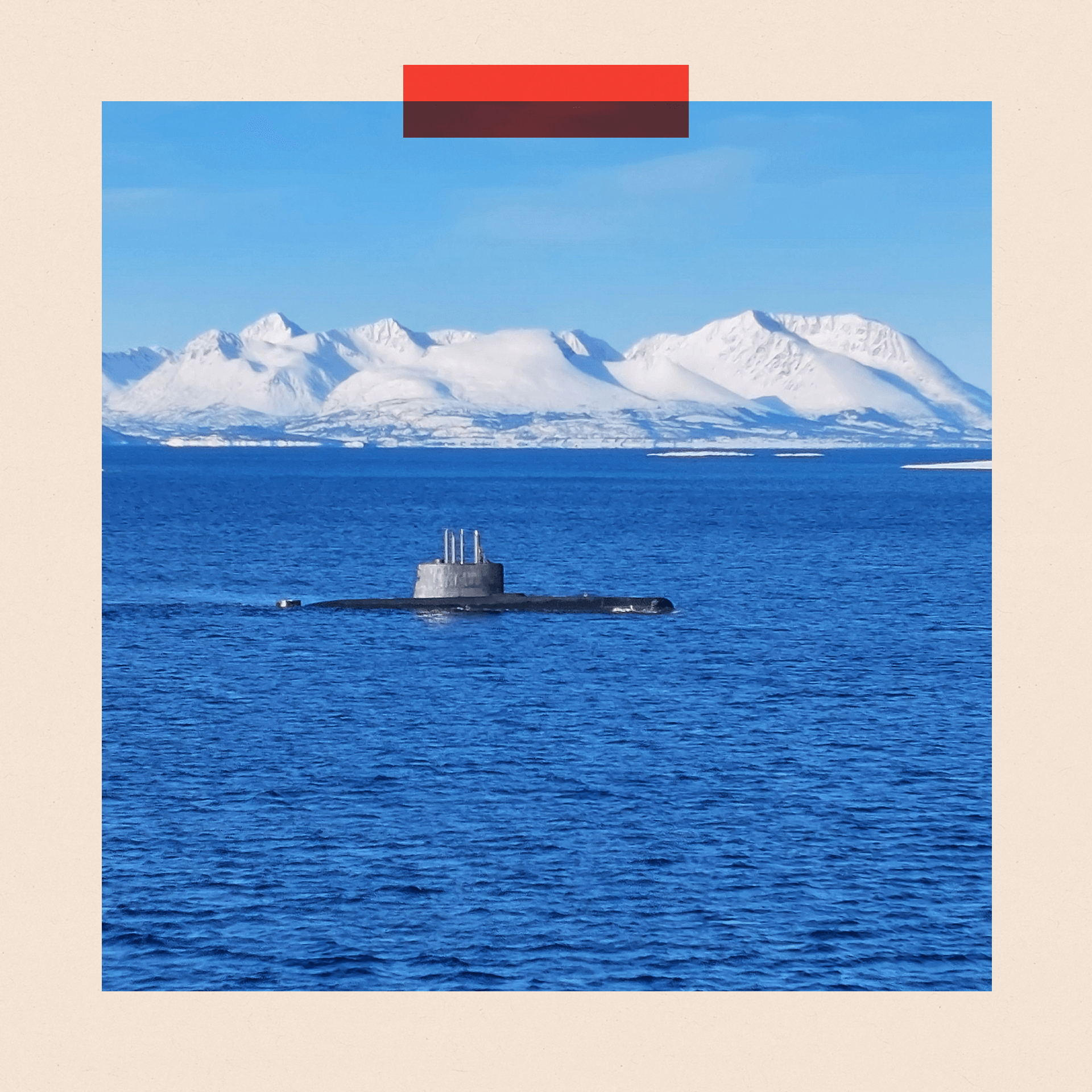

The Kola Peninsula is where much of Russia’s nuclear submarine fleet is based. Russian submarines depart bases here to lurk beneath the Arctic ice ready for an order to launch a strike on their adversary and Moscow sees it as vital for its deterrent and ability to project force.

“The Baltic Sea has become less accessible for Russian military operations following Sweden and Finland joining Nato, which means that the Northern Fleet becomes more important,” Vice Admiral Nils Andreas Stensønes, Chief of the Norwegian Intelligence service, told me in June.

“And there is more reliance on nuclear deterrence. And a fair share of their nuclear weapons are in the Kola Peninsula in the Arctic.”

Vice Admiral Stensønes says that Russia sees it as in its own interest to keep tension low in order to avoid the Arctic becoming more militarised, which would stretch a Russian military still focused on a war on Ukraine.

But Russia’s build up, its desire to project force and its accusations that Western powers are themselves militarising the Arctic are in turn causing alarm, and he warns that the “potential for escalation” is real.

Norway has tended to focus more on lowering tensions, but other countries are sounding the alarm. Denmark’s most recent intelligence outlook warned that Russia will “demonstrate its power through aggressive and threatening behaviour which will carry along with it a greater risk of escalation than ever before in the Arctic”.

The islands of Svalbard are another place to watch. Under a treaty, Norway controls them but other countries, including Russia, are allowed to operate there, making them a potential flash point as Moscow claims they are being militarised to pose a threat to it.

The UK is not formally an Arctic power, but its involvement is growing, in part to counter Russia. One historic reason is something called the GIUK gap, an obscure but strategically important stretch.

To reach the Atlantic easily, the Russian Northern Fleet need to go through the gap - a narrower body of water running between Greenland and the UK with Iceland in the middle.

In World War Two, its importance was one of the reasons for the US establishing a military base in Greenland to deal with Nazi U-boats. In the Cold War and through to today, this chokepoint remains the place to look for submarines, and Nato deploys underwater sensors to hunt for them.

UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy visited the Arctic in late May and announced a new joint scheme with Iceland to use AI technology to monitor “hostile activity” in the region. That means looking for Russian submarines and boats.

However, even though Britain is seeking a greater role, a recent parliamentary report expressed concerns that the UK had “insufficient key military assets, such as submarines and maritime patrol or airborne early warning aircraft, to support an increased focus in the Arctic”.

The recent UK Strategic Defence Review promised to increase the number of submarines but some experts believe more could still be done.

"The Arctic is a region where US, Canadian and European security interests clearly and increasingly converge,” says Peter Watkins, a former senior Ministry of Defence official.

“As a key Euro-Atlantic power, the Arctic should attract more of the UK's attention and resources."

But certain headlines around David Lammy’s visit, such as “Britain’s plan to deny Russia control of the Arctic”, could well rile Moscow. Russia may be building up its own presence but it is highly resistant to others doing the same - it will do what it can to try and stop that happening.

“Russia will seek to deter other countries from threatening its position in the Arctic, making it highly likely that Russia will react aggressively to Western military activities near the Russian Arctic,” according to a recent Danish intelligence report.

“Russia is now willing to take riskier steps in the Arctic and has become more assertive and confrontational,” the report warned.

Power struggles over ‘Polar Silk Road’

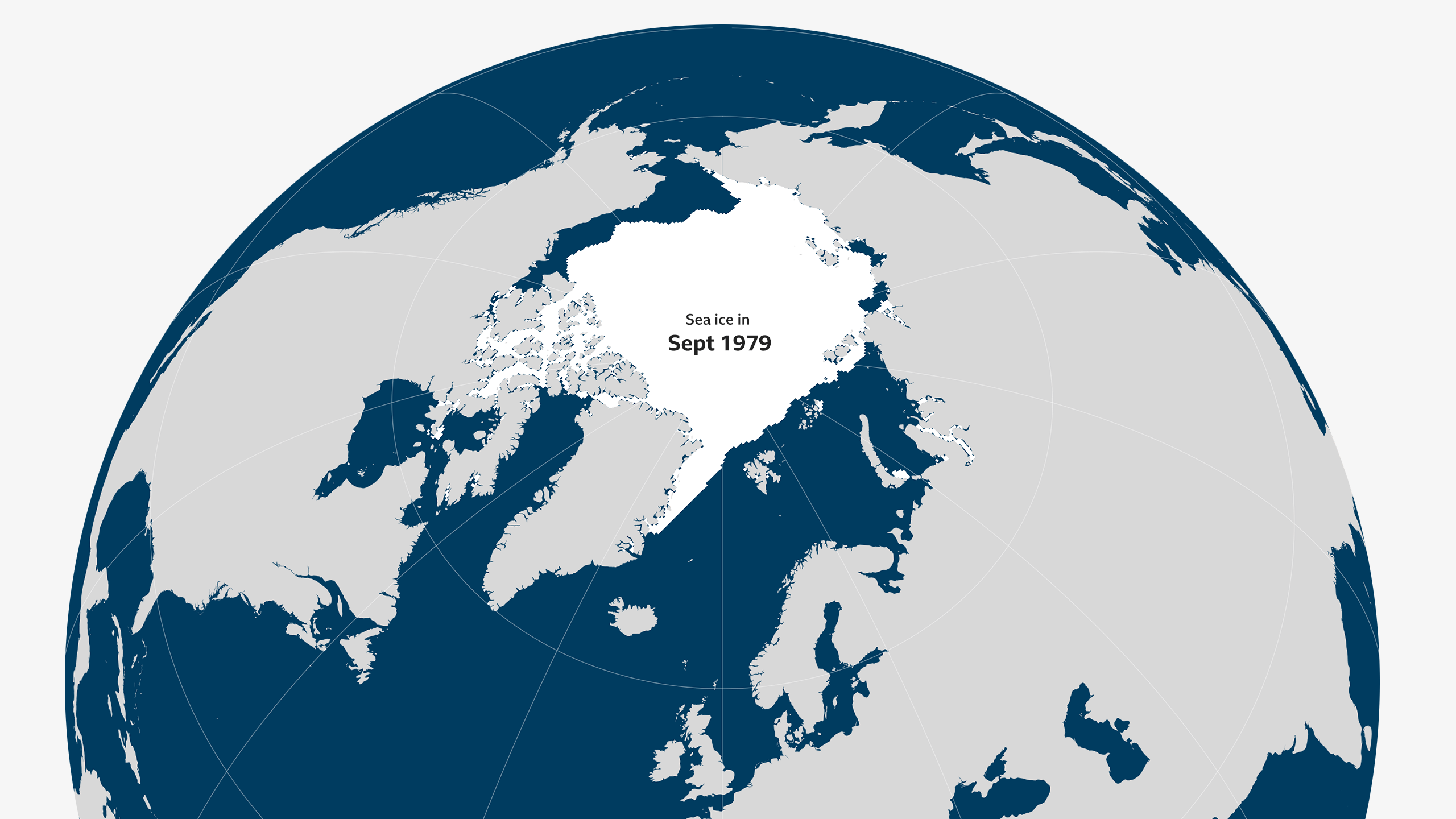

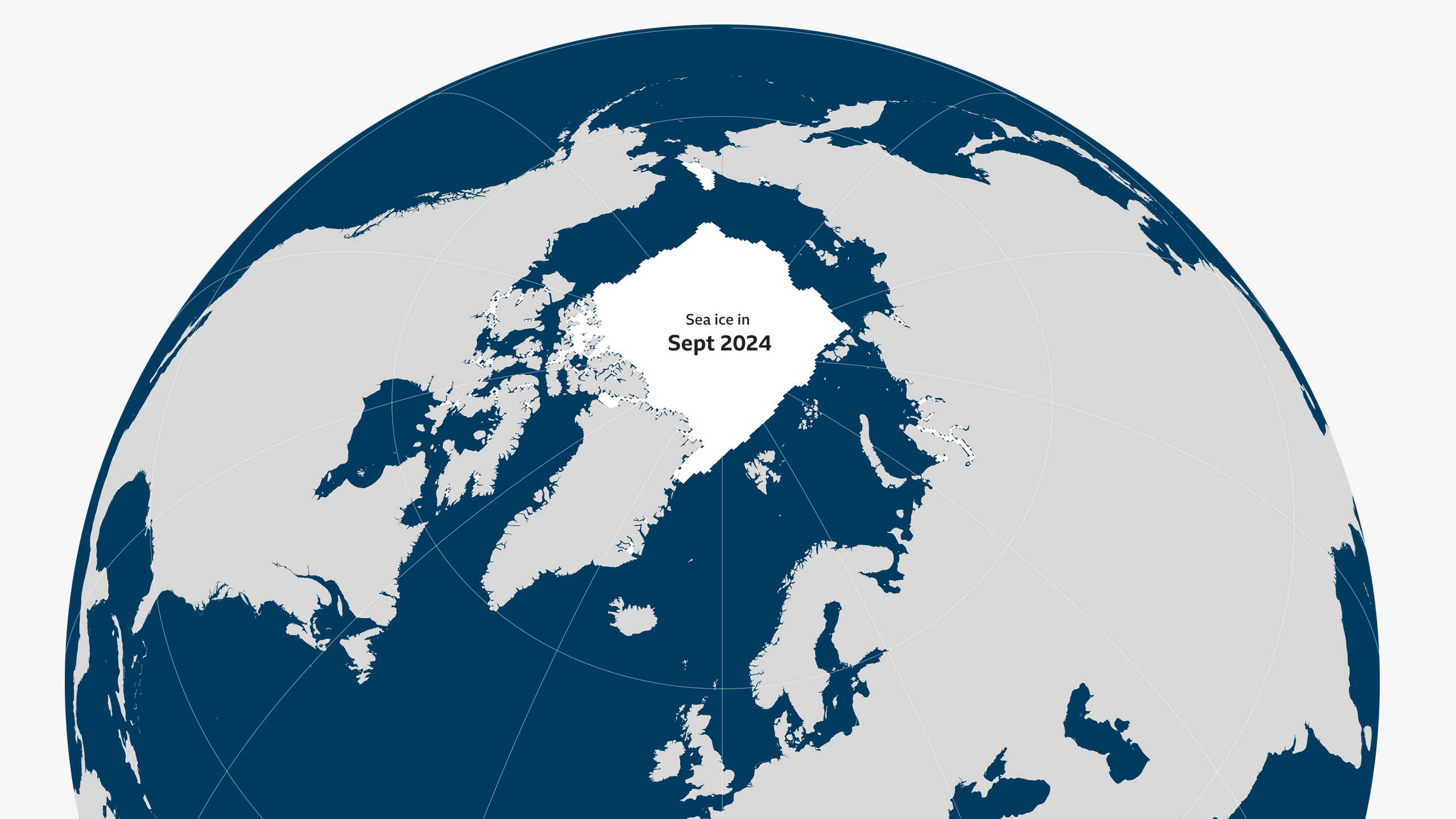

In the waters of the Arctic, a new security challenge is also emerging thanks to climate change.

This year’s UK Strategic Defence Review said it was likely that the High North will be ice free each summer by 2040, but some experts believe this underestimates the speed of change.

Roughly a tenth of Russia’s economic output comes from the extraction of natural resources from the Arctic and melting ice will also serve to make Russia more insecure as it worries about having to defend more of its Arctic territory from other nations, heightening militarisation.

This is also where China enters the frame.

China has called itself a “near-Arctic” state and, despite being a considerable distance from the region and lacking any Arctic coastline, it is becoming increasingly active.

That is driven partly by melting ice opening up the possibility for a new trade route across the North.

For China, a new “Polar Silk Road” offers a new shipping route which is faster and potentially more secure than using the Suez Canal. As a result, it has been seeking to project power.

In turn that has worried Washington, whose global competition with China is now stretching into the Arctic with concerns over influence and resources.

“Beijing has used a hybrid strategy to deepen ties and links to the region from higher education, scientific missions, environmental cooperation schemes, international fisheries agreements, to bilateral strategic partnerships,” says Dr Elizabeth Buchanan.

“This normalises China’s footprint in the Arctic zone and increasingly makes Beijing a partner of choice for Arctic states.”

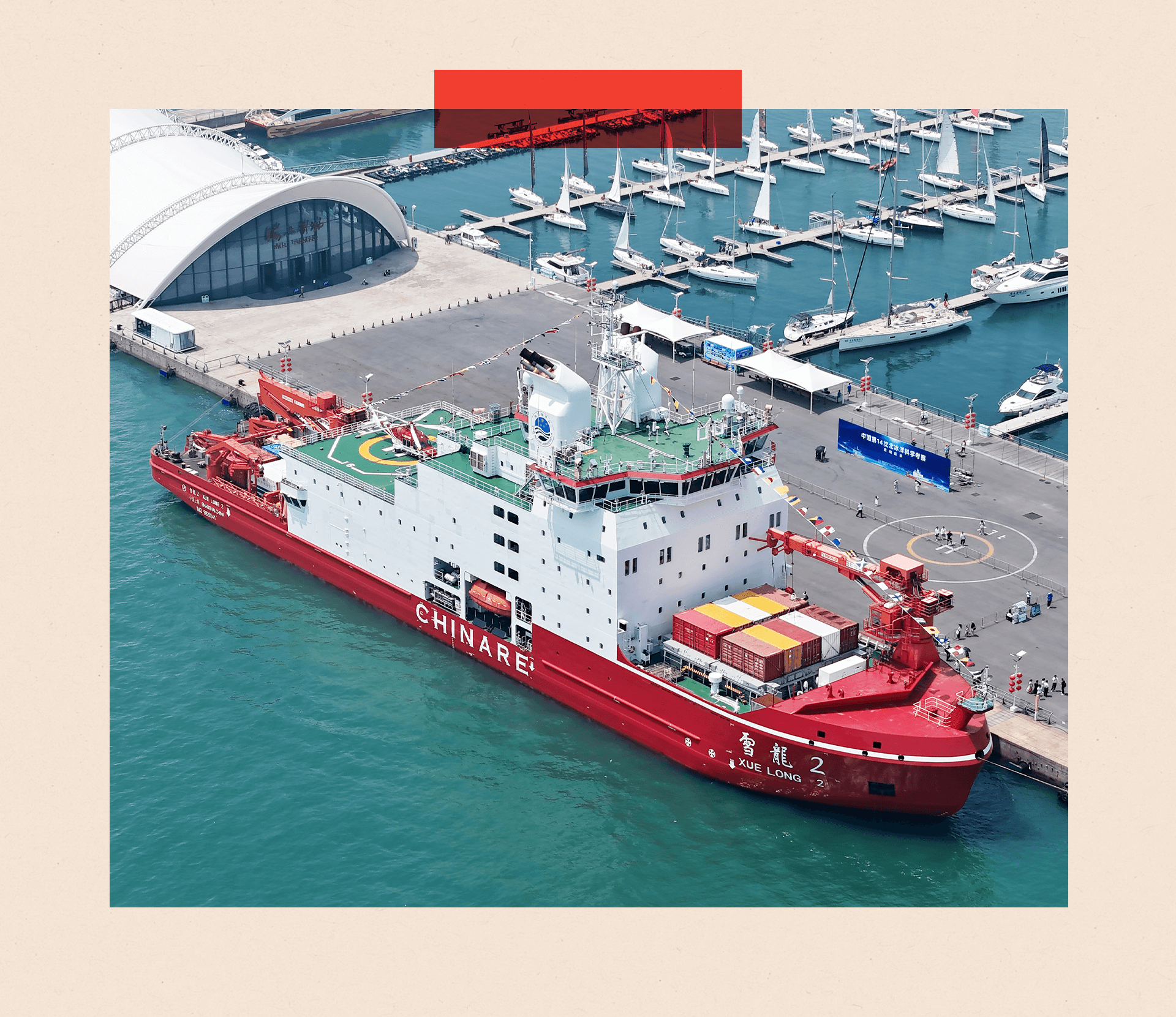

Beijing has rapidly expanded its already large fleet of icebreakers and China and Russia have staged a joint patrol over the Bering Sea near the coast of Alaska. However, Russia is also deeply nervous of Chinese influence growing in a region it sees as its backyard.

Recent leaked documents from Russia’s Security Service, reported by the New York Times, highlighted Moscow’s concerns that Chinese spies were carrying out espionage in the Arctic using mining firms and academic research as cover.

The Arctic has always been an important region for intelligence gathering – primarily what is called signals intelligence, capturing the communications of other nations from secret bases located in the region. But other forms of spying are also on the rise.

A suspected Russian deep cover spy, posing as a Brazilian academic and specialising in Arctic issues, was arrested in Norway in 2022 where sightings of suspected Russian drones have been on the rise. One concern is Russian intelligence interfering in local politics for communities around the Arctic in order to foster division.

And it is not just Russian spies that worry European countries. In recent months, the US is reported to have stepped up its intelligence collection efforts on Greenland, a Nato ally owing to Denmark’s membership. This may have been partly to look for signs of whether Russia and China are trying to covertly extend their influence on the island, but reports of the activity were met with anger in Denmark.

A US diplomat in Copenhagen was then summoned to a meeting at the Foreign Ministry in protest. “You cannot spy against an ally," the Danish prime minister has said.

For European countries, worries about rising tensions with Russia - as well as the reliability of their American partner - are leading to a debate on how they should respond.

“China, Russia and the US are three global powers that meet in the Arctic and we are now seeing pretty sharp competition here,” says Niklas Granholm, Deputy Director of the Swedish Defence Research Agency. “The rest of us will have to influence and adapt as best we can.”

Some nations may favour increased military co-operation while others may fear this could raise the temperature further.

The mantra for those who wanted to keep geopolitics out of the Arctic used to be: “High North, low tension”. But that era is passing thanks to a combination of melting ice, insecurity and assertiveness.

And while it may be in no one’s interest to militarise the region, that is precisely what looks to be happening.

Sea ice data from National Snow and Ice Data Center