Sgt Sandes, an infantry soldier in the Serbian Army, lay semi-conscious on the snowy hillside after taking the full blast of a Bulgarian grenade, and would later recall being wrapped up and bundled away like a rabbit in a poacher’s sack.

“I could see nothing,” the trooper wrote. “It was exactly as though I had gone suddenly blind; but I felt the tail of an overcoat sweep across my face. Instinctively I clutched it with my left hand, and must have held on for two or three yards before I fainted.

“The Serbs have a theory that you must not give water to a wounded man because they say it chills him, so they poured fully half a bottle of brandy down my throat and put a cigarette in my mouth.

“I caught the little sergeant who had helped carry me watching me with his eyes full of tears. I assured him that it took a lot to kill me, and that I should be back again in about ten days”.

Serbian soldiers on the Balkan front

It was November 1916. Sandes was among tens of thousands of Serbian troops fighting, from their base in northern Greece, to try to re-enter their own country, which had been occupied by Bulgarian forces a year earlier.

It took Sandes not ten days but six months to recover sufficiently to rejoin the ranks and to return to the front line. By the end of the war, Sandes would be awarded Serbia’s highest military honour, the Order of the Karadjordje Star.

Sandes is a celebrated national hero in Serbia to this day. That’s all the more remarkable for two reasons. First, Sandes was not Serbian but British - born and raised in Yorkshire.

The British Cemetery at Karasouli is about an hour’s drive north of Greece’s second city, Thessaloniki. A century ago it served as a clearing station for wounded men evacuated from the fighting. Eventually it would hold the remains of more than 1,300 British men.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains 24 cemeteries in Greece, and more still across the border in Macedonia. The largest of these holds thousands of dead. The smallest has just a single grave, that of the poet Rupert Brooke, who yearned to fight but who died from disease before reaching Gallipoli, and who is buried on the Greek island of Skyros.

Compared with the vast and magnificent World War One cemeteries of Flanders and northern France, there is something understated, even apologetic, about the Commonwealth war graves of northern Greece.

There are no shining white upright Portland stone grave markers here. Instead, little concrete blocks ten inches high, known as Macedonian pedestals, mark each grave.

Even before the war was over it was decided that the bodies of those who died should not be returned to their families. Instead they would lie alongside those they served and fell with - an eternal comradeship of the dead.

When I visited Karasouli, a young Greek stonemason was carefully re-engraving the name of Pte John Fulton, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders. It was 19 September, and he’d been killed a century earlier to the very day.

Pte Fulton was from my village in Galloway in rural Scotland. I grew up there half a century after he died and it was then the kind of place where everyone knew everyone. As a child, I read his name on our local war memorial. Had he survived I might have known Pte Fulton as an elderly neighbour - I might have gone to school with his grandchildren.

Few visit Karasouli now, or indeed any of the other Commonwealth cemeteries that are dotted across northern Greece and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Who remembers now why these men were here, what they were fighting for and the cause for which they died in such numbers?

These are the forgotten battlefields of World War One.

British troops began arriving in northern Greece in 1915, to support a larger French force.

They came by sea. Salonica, now Thessaloniki, the port city where they disembarked, had been part of the Ottoman Empire until 1911, when it was taken by the Greeks.

From a distance, the allied servicemen were charmed by its exotic eastern character. It is “a lovely place” one soldier wrote, “a fairy city with white minarets and red roofs”.

But once they were ashore the charm wore off. Salonica was a disease-ridden swamp in summer - insanitary, poor and swarming with mosquitoes. Before long the servicemen were reporting bodies of men and of horses washed up on the shore - casualties of an increasingly successful German U-boat campaign against allied shipping.

1915: A ship on fire in Salonica harbour

But the risk of death in combat was outweighed by something far more deadly - the awful conditions. Go to the cemetery at Lembet Road in Thessaloniki and you will find the graves of 1,600 British servicemen, most of whom never saw a round fired, but who were killed far from the front line by malaria or dysentery or typhus.

More than 600,000 allied servicemen came to the Macedonia front between 1915 and 1918 - French, British, Italian, Greek, and Russian. Their job was to help the Serbs in the war against Austria. But by the time the first troops landed at Salonica they had been overtaken by events. The Serbs were already suffering a catastrophic defeat.

Serbia and Bulgaria had been allies in the Balkan war of 1912, fighting to end centuries of Ottoman rule in south-eastern Europe. But as the Ottoman Empire receded, Serbs and Bulgarians turned on each other and went to war against each other a year later.

Macedonians on the road to Salonica during the Balkan war of 1913

Serbia had ended the Balkan war of 1913 in possession of the land which corresponds roughly to the modern-day independent state of Macedonia. The Serbs called it South Serbia, refusing to recognise a distinct Macedonian identity. But to the Bulgarians it was Western Bulgaria, and the Macedonian “language” was not a separate tongue at all but simply “Bulgarian written on a Serbian typewriter”.

The outbreak of war between Serbia and Austria in 1914 - the opening of World War One - was to give the Bulgarians the perfect opportunity.

The war had begun when a young Serb, Gavrilo Princip, had assassinated the heir to the Austrian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo in June 1914. Princip, at 20, was too young to be sentenced to death for his crime and so lived long enough to see the unintended consequences of what he had done.

1914: The archduke and duchess, moments before their assassination in Sarajevo

The population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was twelve times that of Serbia, a kingdom of just four and a half million people. Even so, the Serbs managed to push back Austria’s first attempt at invasion in the summer of 1914 - the first Allied victory over the Central Powers of World War One.

The Austrians invaded again, and occupied Belgrade in December 1914. The Serbs fought back and recaptured the city.

By the end of the year, the Serbs had lost an estimated 170,000 men. That winter, a typhus epidemic swept through the civilian population, killing hundreds of thousands more. The Serbian government declared that its war aim was now not only the liberation of Serbia itself, but the liberation, from Austria, of all the Slavic speaking territories of the empire, including Bosnia, Croatia and Slovenia.

1915: Refugees during the Serbian retreat

There was further disaster for Serbia in 1915. Bulgaria entered the war in September and invaded in October, just days after Austria and Germany launched new offensives into Serbia.

The Serbian army collapsed and began a long, defeated trek across the mountains of Albania in the brutal cold of a Balkan winter.

Thousands died of hunger, cold and disease. By February 1916, the last of the survivors had reached the Adriatic coast and were evacuated by allied ships and put ashore, finally, at Salonica to rejoin the allies.

Of all the allied burial sites in Thessaloniki the one that receives by far the highest number of visitors today is the Serbian one. It is a vast and cavernous mausoleum that contains the remains of more than 7,000 Serbian soldiers.

Many of them were survivors of the long and deadly winter trek across the Albanian mountains.

The burial site was founded by a Serb veteran called Savo Mihailovic, who was put in charge of collecting the bodies - many of them his friends and comrades - and burying them together on the site of a former field hospital. He never left the memorial, guarding it until his death in 1928. He was replaced by his son, Djure Mihailovic, who guarded the site until his death in 1961. He and his father are both buried in the cemetery. The keeper of the site now is Djordje Mihailovic, Djure’s son and Savo’s grandson.

The Greek authorities have banned further burials in the cemetery but an exception has been made for Djordje, who will one day be the last Serb to be interred there.

Djordje’s presence is a living link with the Serbian experience of World War One. The cavernous interior of the mausoleum he guards is a shrine to the Serb martial tradition. It connects Serbia’s wars against the Ottoman Empire in the 19th Century to both world wars and the wars that Serbs waged during the break-up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

Many of today’s visitors are veterans of those later wars. The kinship they feel with the men of 1914-18 is immediate and powerful.

Then the goal was to drive the Bulgarians out. But the Bulgarians could not have asked for a geography better suited to a defending army. Head north from Thessaloniki and the parched low-lying plains give way to a very different landscape.

The Allied front line in the WW1 Balkan campaign

What separates Greece from its northern neighbours is a chain of mountains, running east to west, that rises steeply and suddenly. It is a forbidding sight. Even in summer the slopes appear black and impenetrable. And it was on these mountaintops that Bulgarian forces dug in. There they would sit, for the rest of the war, ready to swat away successive attempts by the British and French to dislodge them. The allied armies gathering on the plains below were spread out like a map beneath their feet.

(Below: Bulgarian officers on a mountainside in 1917)

On 18 September 1918, the day before Pte John Fulton of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders died, the British launched an offensive against Bulgarian troops dug in along their mountain tops at Doiran, on the Greek border.

It was futile. In one British unit, 500-strong, fewer than 30 men survived. The bodies of many of those killed were never recovered. The Doiran memorial, erected after the war, stands near the Greek-Macedonian border and is engraved with the names of more than 2,000 Commonwealth soldiers with no known grave.

Further west, the main allied force, mostly French and Serbian, was commanded by General Franchet d’Esperey, whom British troops nicknamed Desperate Frenchie or Desperate Frankie. They launched what turned out to be the decisive attack at the end of September 1918.

General Franchet d'Esperey, the French commander in Macedonia, launched the decisive attack in 1918

The Bulgarians abandoned the positions they’d held for three years along hundreds of kilometres of the line. Bulgaria asked the allies for an armistice on 29 September 1918 - the first of Germany’s allies to sue for peace.

The road to the great imperial capitals, Vienna and Budapest, now lay wide open to allied forces. World War One had started in the Balkans - it was now ending there too.

But no nation lost more than Serbia. Sixty per cent of its army of 450,000 died by the end of 1918 - 25% of its entire population were killed in combat or died from disease, including more than half of its entire male population.

The men of the British Salonica Campaign went home to a nation that knew little about what they had done. The disastrous battles they had fought and the long and arduous months they had spent on the barren plains and mountain sides of northern Greece scarcely featured in the national narratives and quickly slipped from collective memory.

There were no victories to celebrate and it was hard to see what their presence in the Balkans had achieved.

In the vast literature of World War One studies, there is almost nothing on this forgotten theatre. The outstanding account is by Alan Wakefield and Simon Moody, in Under the Devil’s Eye.

It is a story of failed and - for the most part futile - offensives. “That evening I sat, clad in an old civvy suit, in my mother’s flat in St John’s Wood,” one survivor wrote of the day he was demobbed. “A strange feeling of loneliness came over me. No longer was the Army there to take care of me; I faced, on my own, a new and strange world.”

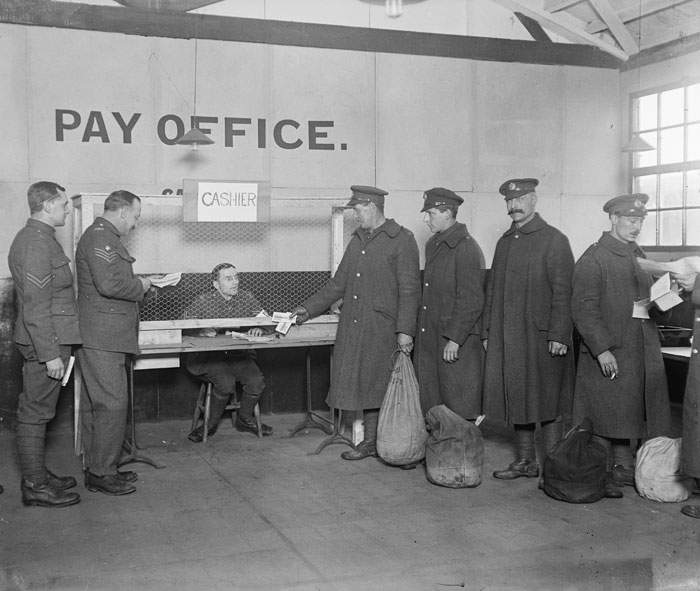

December 1918: Soldiers receiving their last pay packet before demobilisation