There were children playing - doing gymnastics on the grass.

Charlotte joined in with the somersaults until she cut her knee. She didn't think anything of it.

It was June 2016 and Charlotte had been invited to a family barbecue.

Charlotte was a cleaner and a single mother to Katie, then nine, and Shaun, who was 11. They lived in Blackpool.

Everything seemed fine that weekend and Charlotte went to work on Monday and Tuesday as normal. By Tuesday evening she had some backache but had a bath and went to bed as usual.

I thought I was coming down with the flu, severe flu, because I'm never poorly.

Wednesday was Charlotte's morning off and she went to meet a friend. She wasn't feeling great, but still wanted to get out. She drove to Preston, but could barely get out of the car and was struggling to walk.

“I had severe backache, as if I was going into labour.”

Her friend got her home, by which time she was pouring with sweat and shivering. She hoped a couple of hours’ sleep would help. But she wasn't well enough to go to work. Still she managed to get up to collect Katie from school, before falling back into bed.

“I thought I was coming down with the flu, severe flu, because I'm never poorly.”

Katie came in the next morning to ask her Mum to do her hair for school. But it was clear Charlotte couldn’t drive her there.

Charlotte's face had puffed up and had changed colour. Katie knew she needed urgent help.

“You need an ambulance,” she said and went to dial 999.

That call saved her mother’s life.

Within an hour of Katie calling the ambulance Charlotte was in hospital and being put in an induced coma.

She remembers her final words to her family.

“Goodnight everybody. See you. I love you loads.”

Completely different life than we expected, isn't it?

Katie is now a very slight 11-year-old. She looks tired as she opens the door.

The bungalow is close to Katie's new school, and has a ramp up to the door.

“Have you got my tray there sweetheart?” asks Charlotte.

“Coffee?” replies Katie.

“Don't forget my straw.... would you like to pass me my medication and my juice?” says Charlotte.

Charlotte has just got a new battery-powered wheelchair. She moves the joystick with the end of her arm.

There has been amazing progress since leaving hospital and Charlotte is even having meetings with doctors in Leeds about the possibility of a hand transplant.

“I do have prosthetic legs, but for one reason or another I've not been able to get my legs on full time. Although I can walk on them, you know, but it's an ongoing process.”

The carers come in four times each day to help with tasks like dressing and washing as well as making snacks and ready meals. The rest of the time, Katie looks after her Mum.

Charlotte has limited mobility, so Katie has become her legs. Every time her Mum needs her medication, Katie has to get it, along with a cup of water with a straw in it, putting it away when she's finished.

In the morning she makes her Mum a hot drink while getting herself ready for school and fixing her own breakfast as well as finding her Mum's phone and taking it to her.

Katie also helps get her Mum into the shower and sometimes washes her.

When there’s not much left in the fridge, Katie has to be aware and regularly pops to the shops. She finds important bills Charlotte needs to look at, she puts the rubbish in the bin and she puts the shopping away.

Katie is also Charlotte's hands. As her mother can no longer hold or manipulate things, Katie has to fetch everything her mother needs and even write for her. She collects the post, answers the door to deliveries, opens the post and parcels, fills and boils the kettle, helps Charlotte with her clothes and finds her bag when they go out.

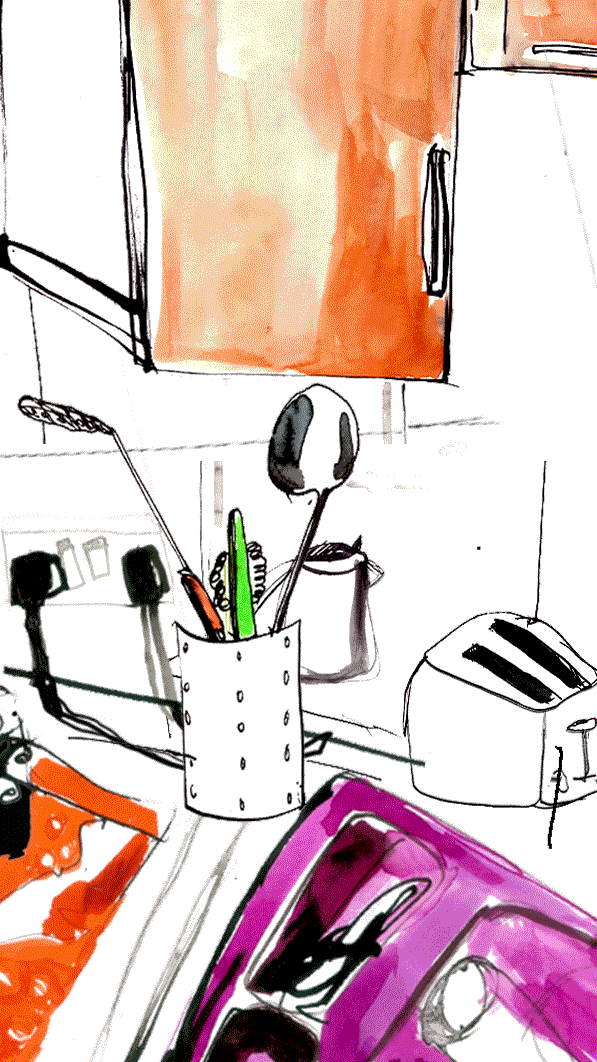

“She's had to grow up a lot - very quickly,” says Charlotte, who finds it very frustrating not being able to do all the things she used to.

When they decide to head into town on the bus, Katie zips up her Mum’s coat and locks the door as Charlotte wheels down the ramp.

On the bus, Katie has to make sure the wheelchair is in the right spot, before pulling down the handle to secure it.

“You're doing a grand job,” says one of the passengers to Katie. “She is,” says Charlotte.

In town Katie goes to the cash machine for her Mum, before they get the shopping they need, which Katie hangs on the back of the wheelchair and piles up on her Mum's lap.

“Her life has drastically changed. She's gone from Mum doing everything for her, and now Mum has to ask her to do everything,” says Charlotte.

On the way home, Katie gets a ride as she balances on one of the arms of the wheelchair, her arms round her Mum.

Back at home Katie seems an energetic and lively young girl. She talks about school, make-up, what she’s watching on her iPad and how she talks to friends until late in the evening. She loves gymnastics and she cartwheels and handstands her way around the room and off the furniture.

She proudly shows off the certificate for being a young carer she was awarded at a council reception.

In the kitchen, Charlotte has to rely on Katie to use the cooker, microwave and washing machine - lifting things, doing some washing-up, clearing up and putting things away. Katie has to keep the house running.

“She's been learning to iron. She's been learning to cook a few simple meals... normal things an 11-year-old wouldn't be doing.”

Charlotte recently had a scare. She started choking and panicked. She went into the bathroom where she was sick. Katie didn’t realise and only found her Mum later.

“That's my main worry, because it's life-threatening,” says Katie. Afterwards she lay awake with the episode preying on her mind.

“She's a little worrier,” says Charlotte. “If I've had a bad night, [she’s] worrying if I'm going to be OK, if I'm going to be poorly, am I going to be here when she gets home from school.”

Katie’s memory of finding her Mum - in a critical condition from sepsis - has had a deep and lasting effect on her.

She admits there have been times she has cried herself to sleep and can easily get upset, angry or feel down.

“She has suffered with anxiety,” says Charlotte. “She felt scared to speak to me about her feelings, thinking I'd get upset. Now she knows that she can talk to me and scream and shout and cry if she needs to, and everything's going to be OK.”

The after-effects of Charlotte’s illness have been mental as well as physical.

“I have good days and bad days like anybody else. There are a lot of side-effects of sepsis, afterwards, [like] hair loss. I’ve got a liver investigation going on at the moment. I’ve never suffered with anxiety or depression before… but I’m getting help for that.”

The respect that mother and daughter have for each other, and the strong bond between them, are clear.

“She's very courageous, she's very loving, very caring, she's hands-on, she just wants to help. I love her to pieces,” says Charlotte.

But there have been questions from Katie as she learns to cope with what she’s lost.

“We've had our moments when she's asking, ‘Why us? Why did it happen to us?’ I don't know the answer. The main thing is I’m still here,” says Charlotte.

She turns to Katie: “I’m still alive and if it wasn’t for you then this could be a different story.

“I’ve heard her saying so many times, ‘I just want my old Mum back.’”

Charlotte understands how her daughter feels and wants to do more as a mother again and have fun days out.

Katie misses so many things about the old Mum - especially her cooking, now they rely more on ready meals. “I hate microwave meals, they’re tasteless.

“Seeing my Mum struggle - it upsets me because I remember ages ago when she used to do everything.

“I'm mum, I’m your mum right now,” says Katie.

Charlotte acknowledges the scale of her need for Katie’s care.

“It'd be miserable, dull and lonely - a very, very lonely life [without Katie’s help]. It's unbearable to think about to be honest.”

She feels that Katie misses out on some of the normal things that children do. It’s a common emotion among parents of young carers.

“I feel I've taken away her childhood, or should I say sepsis has taken her childhood away. It's a cruel world but we're just making the best of a bad situation.”

Since Charlotte became ill the family have had help from a host of services, organisations and agencies.

Countless assessments, appointments, forms and meetings have had to be navigated. Charlotte says she couldn't have done it without Citizens Advice and Lancashire Wellbeing Service.

She describes getting their new house as an early Christmas present, and is thankful to a housing officer at Blackpool Council who made strenuous efforts to find the right home.

Charlotte is on what's described as a full-care package - she has been assessed by a social worker who has confirmed she needs high-level help each day. It's part-funded by Lancashire County Council now that they’ve moved outside Blackpool, with Charlotte paying a top-up of about £200 each month.

Carers from a private company come for an hour in the morning to help her get up, dressed, washed and have breakfast, half an hour at lunchtime, an hour at teatime to help Katie with the evening meal and washing up, and half an hour at bedtime.

Charlotte is happy with the level of care. But Katie says she wants “more carers, more help”.

They live on a number of benefits. Personal independence payments have replaced disability living allowance for people who need help with daily activities or getting around because of a long-term illness or disability.

They also receive employment support allowance which used to be called incapacity benefit - and they get housing benefit. Then for Katie, Charlotte receives child benefit which is £84 per month as well as £45 per week in child tax credit.

Despite having extra costs, such as taxis to medical appointments, Charlotte says they get by. She hopes they might even be able to get away for a holiday next year.

Katie also has a range of professionals helping her. Charlotte says the help took some time to be put in place. Katie’s social worker has arranged a needs assessment for Katie - all young carers are supposed to get one of these. The council then brought in the children's charity, Barnardo's, to work with Katie and she was introduced to their support worker, Lauren.

The charity worked with nearly 3,500 young carers in the UK last year.

Katie has had one-to-one sessions where she could talk about how her Mum's illness has made her feel and to explore ways to cope with those feelings.

Barnardo's also arranged some group work that looked at topics like keeping healthy, first aid and being safe on the internet. Here Katie got to meet other young carers and was taken out on trips.

What fun does Katie think young carers need?

“A place that does make-up or things like that and then, for the boys, Xbox or PlayStation rooms - and then a play area for the younger ones.”

Lauren, from Barnardo's, was also involved when Katie moved from primary to secondary school to make sure support at school continued.

The school has assigned Katie a mentor and she also sees a counsellor - the same one she saw at primary school.

After 12 months, Barnardo’s reviewed the help they provided to Katie and, according to Lancashire County Council, decided she was coping well and that the support could be “stepped down”.

Charlotte wishes Katie still had her support worker and feels it was due to budget constraints at the council. The council says if the family needs more help there could be a reassessment.

Katie knows that she can speak to staff at school if she is having problems. “If it's been a really bad week then they will try to do their best to help.”

Her school understands Katie’s situation at home, and work to support her whenever needed.

There should be more options for activities and places where Katie could go for time apart, Charlotte feels. “I feel there should be more after-school clubs that don't cost the earth.”

Access to young carers’ group activities that promote relaxation is key, says Emma James, policy officer at Barnardo's. “They feel less socially isolated, they're talking to other young people in the same situation as them and that sort of provision has been cut massively across the country.”

Charlotte feels she has had to deal with too many different workers.

“We've had social workers, key workers involved, but… they've got a time limit of how long they can work on a case. There's no continuity.”

Katie feels there needs to be more help. “We all know that I need more support than what I get.”

We ignore these children at our peril and at the peril of these children’s futures.

“Well done, that's brilliant, that's brilliant, that,” says Charlotte.

Katie has come home with a certificate from school for work she's done on additional English tasks she's been set.

Charlotte is concerned about Katie's progress at school. After the disruption and the house move, Charlotte now thinks Katie is about two years behind where she's expected to be.

One-to-one tutoring is being laid on at school to help bring Katie’s grades back up.

“Sometimes if I think about my Mum way too much, like every day - I'll go straight off my work, and then get angry with my teacher,” says Katie.

This is not an unusual problem for young carers, explains Prof Saul Becker. Caring before school can affect their ability to go to school, their concentration at school, their ability to stay awake in classrooms or to do their homework.

The impact of a disrupted education for young carers stretches well beyond school. Emma James, from Barnardo's, says it can have an impact on their adult lives.

“We know they're less likely to go into higher education because of their caring roles, they're less likely to be able to get a steady and secure job and they're much more likely to have mental health issues.”

Katie already has dreams of what she might do when she grows up. “A YouTuber, a model and a beautician.”

Sadly, there is another challenge that many young carers face - socialising and making friends both in school and at home. Many will find it difficult to play and interact with those who aren't young carers, explains Prof Becker.

Katie says the hardest thing about being a young carer is the bullying.

“Someone actually did say to me, ‘Lol your Mum's gonna die’.

“These girls were like saying, ‘Ah, you stupid cow’ and things like that to us.

“I've heard someone say, ‘You and your mum are silly bitches.’”

Katie has had to cope with these comments by children at both her primary and secondary schools since her Mum became ill.

“It's quite horrible what I'm going through and then I'm coming to school. I've not come to be called horrible names or anything. I've come to school to learn.”

The school is supporting Katie and says it acts upon any reports of bullying.

Katie and Charlotte both describe the lack of understanding of their situation as the main problem. People make judgements about them and how they feel.

Katie has found her own way of dealing with some of the remarks she's suffered. She tells herself it's down to ignorance about her situation.

“At the end of the day, I turn my back on those people.”

Some people have been more understanding after Katie explained the situation to them. She had to describe it a few times, but once she had, their reaction was: “We're so grateful she's alive.”

Katie’s situation is not unusual.

The last census in 2011 found there were 166,000 young carers in England aged five-17 years.

But charities and organisations working with young carers have long thought this was an underestimate.

There is a certain stigma, says Prof Becker. Many families where someone has an illness or disability would not like it to be “on record” that the children are carrying out caring roles. They worry that there may be a perception by the authorities that they're not coping.

New research carried out by BBC News and Nottingham University presents a very different picture.

The questionnaire was completed by 925 children across England from two year groups - 11 to 12-year-olds and 14 to 15-year-olds.

If the survey was extrapolated across England it would correspond to more than 800,000 secondary-school age children carrying out some level of care.

Of those, the survey suggests more than 250,000 young carers are carrying out a high level of care, with 73,000 taking on the highest amount of care. Katie is one of them.

“The fact that there are so many vulnerable children who are slipping through the net is one of the biggest scandals of our generation,” says Javed Khan, chief executive of Barnardo's.

“These findings tell us, that as a nation, we are relying very heavily on children to provide care to other family members and in some cases to a number of family members,” says Prof Becker.

While the survey only covered England, the prevalence of young carers is an issue across the UK. In Wales, the official figures say there are 7,000 but research suggests a figure four times higher. In Scotland, the Carers Trust says there are 29,000 young carers.The trust says there are 30,000 young carers in Northern Ireland.

Within the past five years two new pieces of legislation have been brought in, giving significant new rights to carers in England - the Children and Families Act 2014 and the Care Act 2014.

Young carers have the right to a “carer's assessment”, which is the duty of the local authority. These assessments measure the effect on young carers’ wellbeing - health, education or friendships – and whether they should continue carrying out that level of care.

“There are many children in this country whose burden of care is so extreme that it would be really difficult, if not impossible, for many adults to do those kinds of care-giving roles for other people – but we are expecting children as young as five and six to [do them]. They need to be assessed and... receive services that reduce the amount of care-giving,” says Prof Becker.

But there are young carers not known to the authorities and others have to wait too long for an assessment, some experts suggest. Many local authorities are under intense financial pressure, says Prof Becker.

“Some of the authorities are providing good services… [but] there’s very little in large parts of the country.”

Once the assessment has been carried out, the young carer and their family should be told of the support they need, which should then be provided by the local council, the NHS or an organisation commissioned to work with young carers.

But services can be patchy.

Government guidance says children are not supposed to undertake inappropriate or excessive caring roles that may have an impact on their development.

The Care and Support Statutory Guidance 2016 lists duties which would be considered inappropriate:

- personal care such as bathing and toileting

- strenuous physical activity such as lifting

- administering medication

- maintaining the family budget

- emotional support to the adult

The UK government says its Carers Action Plan will help young carers over the next two years and says it will soon explore long-term solutions.

“Young carers make an invaluable contribution in looking after their loved ones. That’s why we changed the law to improve how we identify and support them and their families,” a spokeswoman says.

Many experts believe that more could be done.

“To some extent, as we face more austere times,” says Prof Becker, “the prognosis for young carers and young carers’ services gets bleaker and bleaker.”

In the past two years, Katie and Charlotte have been through intensely challenging times.

“My Mum is my inspiration and my hero.”

Katie wants people to know this is how she views her Mum and that she's not looking to be pitied.

Charlotte also has a message for those who would be unkind to Katie or other young carers.

“Stop and think twice. But try and put yourself in their shoes for five minutes - they don't want sympathy, they just want to be treated as a normal person, who's doing an absolutely fantastic job behind closed doors.”

They have fun doing all the normal sorts of things that mothers and daughters do. Katie loves spending time with Charlotte.

“Going shopping and watching movies... and eating popcorn!”

I leave Katie and Charlotte cuddling up on the sofa, watching TV.

What does her Mum mean to Katie? She doesn’t need to think about it: “The world.”