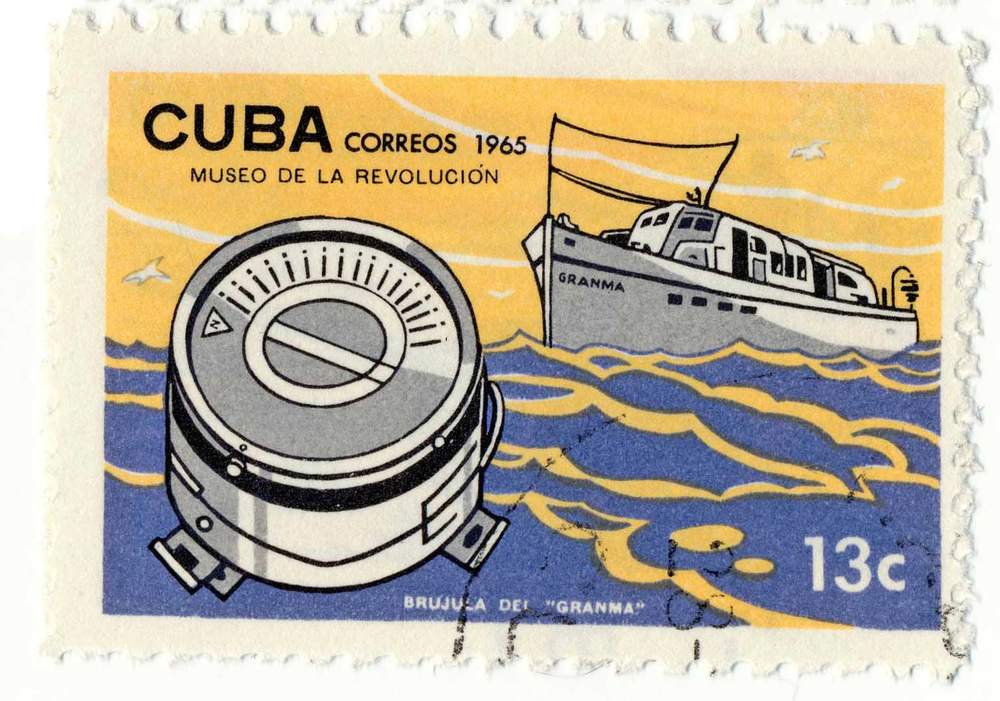

The boat was barely seaworthy and heavily overloaded with men and equipment. For seven days and nights, the crew had attempted to navigate the treacherous seas but the ship was unfit and letting in water.

Almost all the men on board were unwell – seasick or weak with hunger and thirst.

Now, arriving two days later than planned and miles from the rendezvous, the ship had run aground in thick mud.

A Cuban postage stamp celebrates the Granma's voyage

As Che Guevara would later observe, the supposedly triumphant return to Cuban soil of Fidel Castro and his revolutionary force in December 1956 “wasn’t a landing, it was a shipwreck”.

In all, 82 men stepped off that vessel, Granma, bedraggled and dispirited.

It soon got worse. In the foothills of the Sierra Maestra they were ambushed by the Cuban army and reduced to just a handful of guerrillas, among them Fidel Castro and his younger brother, Raúl.

From that ignominious start, they eventually defeated Fulgencio Batista’s military regime. Facing 40,000 men and far superior weaponry, it was one of the most successful guerrilla campaigns of the 20th Century.

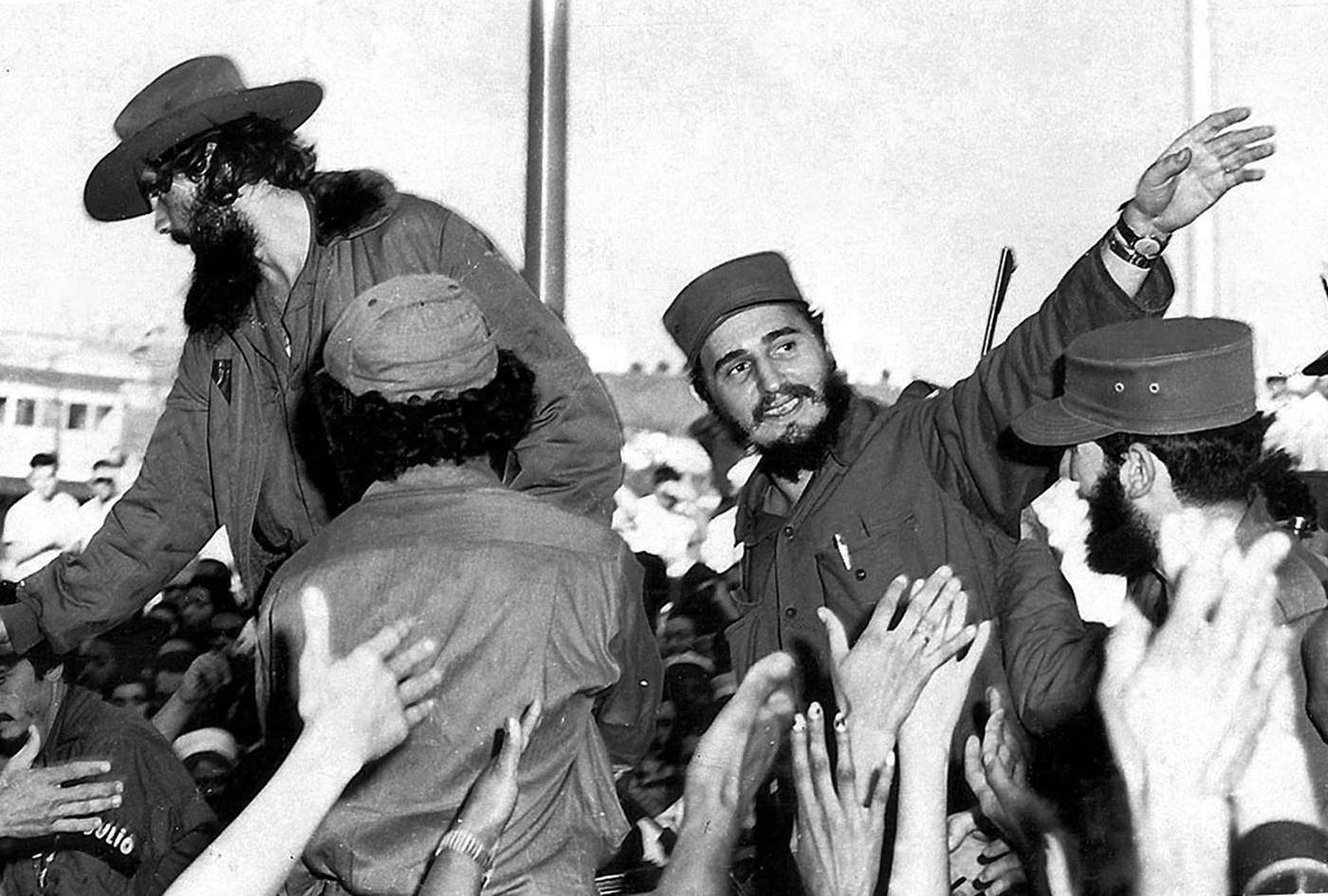

(Below: Fidel Castro waves to crowds in the Cuban capital Havana in January 1959, shortly after his victory over Batista)

Perhaps more incredibly, though, they have stayed in power until today. Between them, the Castro brothers have spent almost 60 years at the helm.

The mark they have left on the island, shaping it into a one-party communist-run state, is indelible.

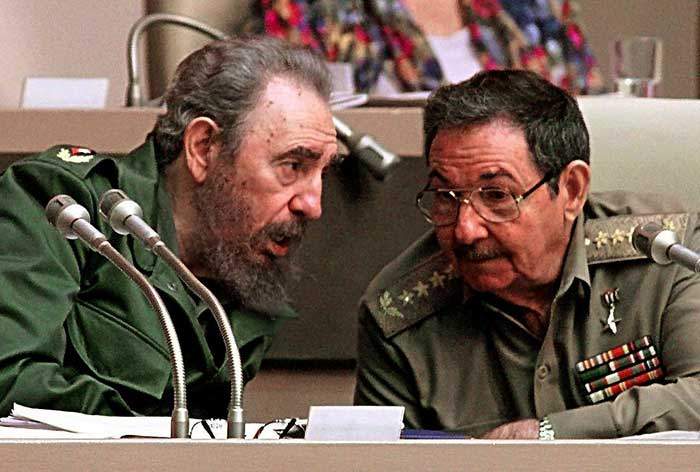

Fidel and Raúl in 1999

Now, a turning point beckons. The Father of the Revolution, Fidel Castro, died in late 2016 and Raúl Castro is retiring from the presidency. Cuba is about to be governed by someone other than a Castro for the first time since 1959.

So, after six decades, what kind of country will they pass on?

As the elderly Castro slipped into his final moments, he could reflect on a long and contented life.

Though frail in body, he’d stayed mentally agile until the very end and his adoring children and grandchildren were at his bedside.

He was stubborn - a family trait - and a fighter to the last. For nearly nine hours the doctors attempted to save him. But it was not to be.

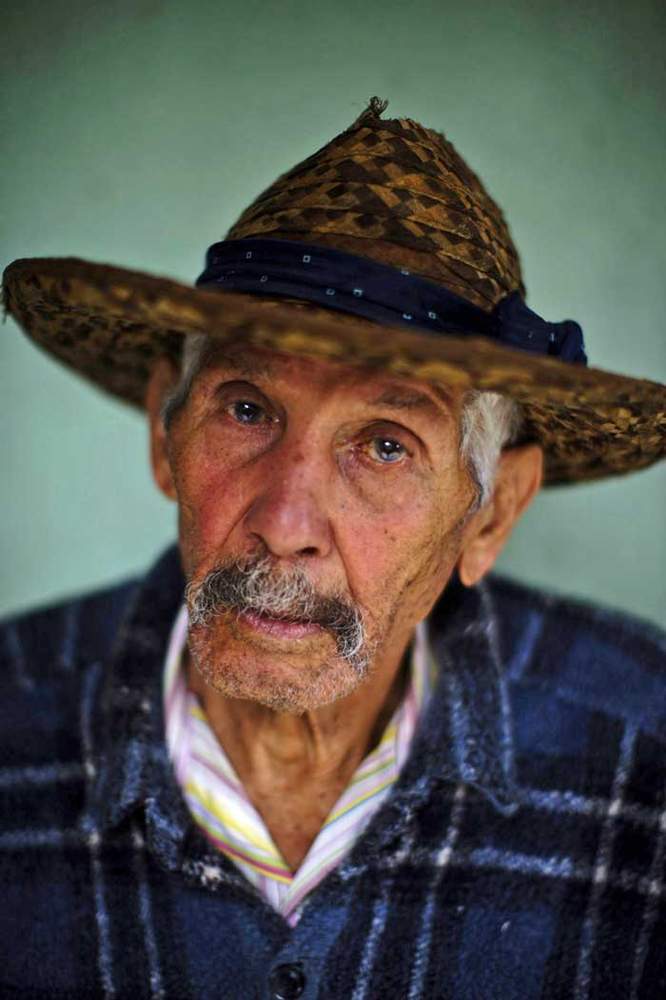

This was Mártin Castro, half-brother of Fidel and Raúl, and he died in September 2017 only a stone’s throw from where he was born - in Birán. He had suffered an aneurysm, aged 87, a year after Fidel’s death.

Mártin Castro, pictured in 2016

Although the two men shared a father and played together as children, there were perhaps no two lives in Cuba quite so different as theirs.

One became the founder of the Cuban Revolution. The other never left home.

An icon of the Cold War, Fidel Castro led Cuba for almost 50 years, installing communism on an island barely 90 miles off the coast of Florida. “Right under the noses of the imperialists,” as he would later famously say.

After the revolution, in 1959, his little-known half brother Mártin was offered the chance to move to Havana to take up a role in government. He turned it down. A simple man, Mártin was happier among his animals and the sugar cane fields of their hometown.

“I often wonder what would have happened if Dad had joined with Fidel,” says his daughter, Josefa Beatriz, her grief still evident, “but he never wanted to.”

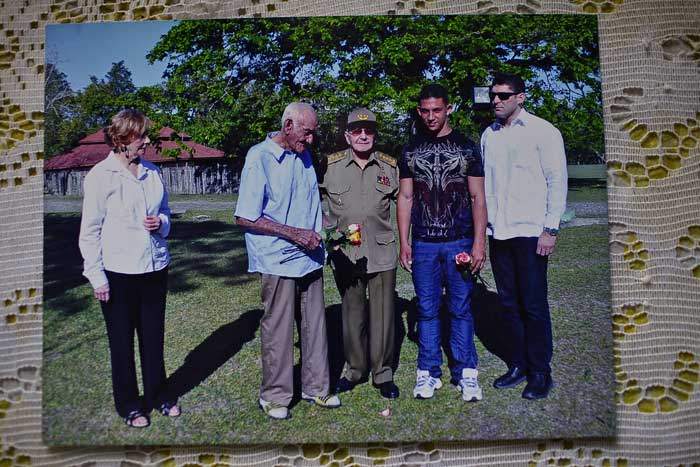

A Castro family photo featuring Mártin and Raúl

“My father never studied but he shared their intelligence," she recalls with fondness, passing a finger lovingly over his photograph. The family resemblance, especially to Raúl, is striking.

The Castro family home, Finca Las Manacas, is now a museum, painstakingly restored as a monument to Fidel and Raúl's rural roots. The town’s historian, Antonio López, guides me around the estate.

Finca Las Manacas, the Castro family estate

Birán, he says, was the town that Castro built.

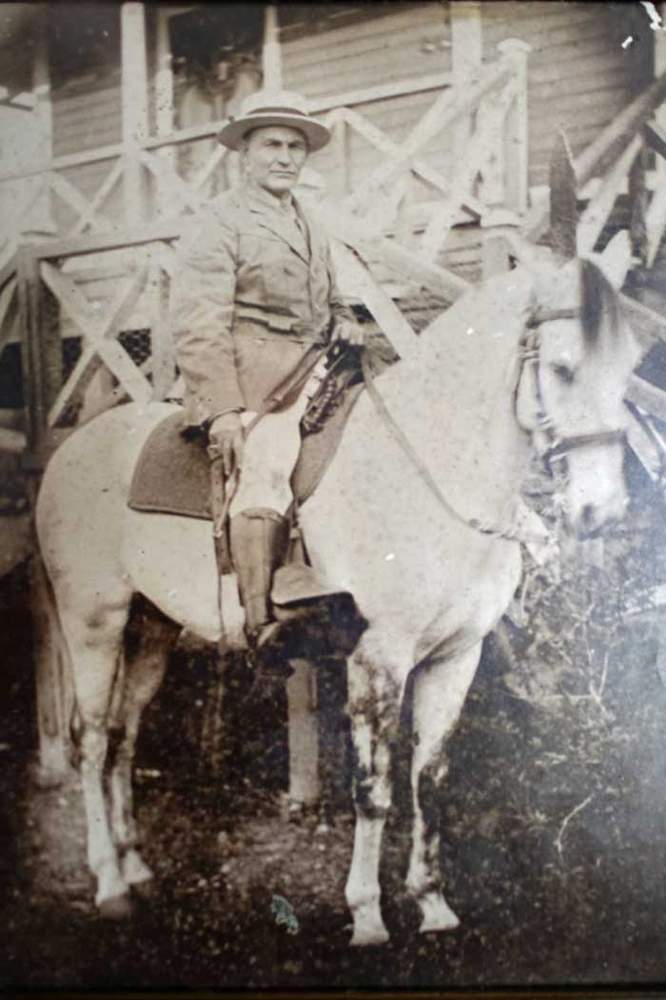

Fidel’s father, Ángel Castro, first came to Cuba in the 1890s from the Spanish region of Galicia as a conscript to defend colonial rule during the Spanish-American War.

When he returned to the island shortly after its independence in 1898, he began working in the mines and later the sugar cane plantations for the American giant, United Fruit Company.

Ángel Castro, father of Fidel

By the early 1910s, he was on the path to wealth. He had bought a little land on the side of the Camino Real, a muddy route between Santiago de Cuba and Nipe Bay on the northern coast.

Little by little, that farm grew into a fiefdom typical of the era: a school, a general store, a lumberyard, a bar, a blacksmith, rustic huts for the Haitian sugar cane and timber workers.

Antonio shows me the tiny schoolroom where Fidel first sat in on classes before being sent to study under the Jesuit priests in Santiago and Havana.

As one guide walks past, she repeats the official story to tourists - how the impoverished conditions of the indentured Haitian sugar cane cutters left a lasting impression on Fidel and Raúl.

“Fidel once said he was glad to be the son, not the grandson, of a landowner as there still wasn’t a family culture of privilege or entitlement,” says Antonio.

Ángel wouldn’t live to see the victory of the socialist revolution nor his sons become the two most powerful men on the island. He died in 1956 and is buried alongside Fidel and Raúl's mother, Lina, in Finca Las Manacas.

However, for at least one other son, life never really changed much from those early days of rural tranquillity.

Over sugary black coffee in her living room, Josefa explains how Mártin had left them a little land, a few head of cattle and the cramped but welcoming home where we are sitting.

Birán retains its sleepy village life. Men gather in the tiny plaza around the state-run shop, sharing a little rum after a morning in the fields or buying fizzy drinks and cheap ham sandwiches in the subsidised cafeteria.

Mártin's rudimentary concrete house was part of a plan by Fidel to build 400 homes for the townsfolk, in contrast to the workers’ flimsy wooden huts on his father’s estate.

Rectangular and boxy, with a bathroom hidden behind a curtain, all along the street the homes are uniform, except for a few which stand out with bright pink, yellow or green facades.

Most have a narrow front porch. Mártin used to sit on his in a rocking chair and watch Birán go by.

In the end only 218 of the 400 were completed.

At the wake, it seemed like neighbours from all of those 218 turned up to pay their respects, his daughter recalls.

“Everyone knew him, would stop by and chat to him. People used to ask me why I didn’t take him to live in Havana but he was happy here.

“He’d say, ‘I don’t want wealth. These are my riches’,” and she motions towards the fields.

The ferry to Cayo Granma can get pretty crowded.

Just one Cuban peso (5 US cents; 3p) each way, it is the easiest and cheapest way to reach the island, which lies at the mouth of the Bay of Santiago. The deck is full of boxes of frozen chicken thighs from Brazil, a motorbike rests precariously against the railings and on the benches inside a group of high school kids are giggling and shouting over one another.

Few tourists venture out to the sleepy fishing village but one suspects most locals prefer it that way.

“They’ll have to set me on fire before I leave this island,” jokes Rosa Caridad Valverde, who has lived on the tiny islet her whole life. “Then, after they put me out, I’d swim back to the Cayo!”

Now in her late 70s, she is suffering from high blood pressure. Nothing serious, she insists, but she has come to see the family doctor to pick up a repeat prescription for her pills.

Rosa is sitting in the shade waiting for Dr Clara Luaces, who is attending to her patients inside a spotlessly clean clinic.

“Given how cut off this island is from the city, we have the basic equipment needed to treat people,” explains the doctor, her stethoscope still around her neck. Clara is a very direct but warm woman in her 50s who takes pride in living among the community itself, something she says is key to the concept of primary healthcare in Cuba.

“There are 651 inhabitants living here,” she says, nodding at the wood-and-tin houses which snake up the hillside towards the church. “There is a launch to take emergency cases or pregnant women to the mainland, although we have saved several lives here on the island ourselves,” she adds with a hint of pride.

Rosa Caridad is thankful for the service. Unprompted, she offers glowing revolutionary praise: “The greatest thing for a country is not food or clothes, it’s health and education. And we get both of them for free.”

These are the two pillars of the Cuban Revolution, the social achievements most synonymous with Cuba under the Castros.

In fact, to suggest that there are inadequacies in either - to point out that they are in dire need of investment and modernisation - borders on blasphemy to some government officials in Cuba.

Asked what she would most want from Raúl's successor, Clara speaks carefully. She is only prepared to say that bureaucracy remains an obstacle in Cuba and that it isn’t easy to get by on a salary of about US$35 a month. Even then she quickly corrects herself: “But I’ve seen my wages increase more than most in recent years.”

Plus, she adds dutifully, the US economic embargo on Cuba should be lifted. It’s a refrain that is repeated endlessly across Cuba. From supplies of medicines to new strains of seeds, the embargo – or “blockade” as Cubans call it – is now in its 58th year and is blamed for much of the island’s economic stagnation.

But there are, of course, several homegrown challenges facing Cuba’s healthcare system. Off the record, some doctors and nurses will say that infection inside hospitals is a significant problem.

And while treatment remains completely free, a significant burden of care falls to the families. They must provide the sheets, pillows, and sometimes even source the meals and basic antibiotics their loved ones require.

Nevertheless, Clara says, in the rest of Latin America very few can count on the same free medical attention that Cuban doctors provide.

The Pan-American Health Organization, among others, has been fulsome in its praise, especially in the fight against infectious disease on the island.

Back on the mainland, I visit the spot where it all began, where the opening salvo of the Cuban Revolution was fired - the Moncada Barracks.

On 26 July 1953, Fidel and Raúl led an ill-equipped uprising in Santiago against Batista’s brutal regime by attacking the barracks.

The attempted coup was crushed within hours and the plotters rounded up and tortured. The Castro brothers were fortunate not to be among them.

In a flourish typical of the Castros, once they took power, they turned the military base into a school. Today it houses several schools under one roof as well as a museum about the uprising.

Education is another source of huge pride in Cuba. The country eradicated illiteracy in rural regions in the early 1960s and its commitment to higher education and scientific research is internationally recognised.

At the turn of the 21st Century, a World Bank study of Latin America and the Caribbean found that Cuba ranked first in maths and science at all school grades and for both males and females. The report also described Cuba’s schools as the “equals” of schools in many OECD countries.

Education remains a key tenet of the revolution. But today resources are scarce, budgets stretched thin and official statistics suggest a worsening teacher shortage.

Thousands of teachers are absent or have apparently abandoned the profession altogether in favour of the private sector, where more can be made in a day renting rooms to tourists or giving private classes than in a month as a state educator.

In the shaded patio at Moncada, the children are lined up in neat rows besides a plaque marking the spot where the bodies of the revolutionaries killed in the Moncada attack were laid out.

“Pioneers of communism,” calls a child to the entire student body assembled before her.

“We will be like Che!” comes their resounding response.

It is the slogan chanted every morning by schoolchildren across the island, a lifelong dedication to the values of socialism as personified by Che Guevara.

Afterwards, we are ushered into a classroom to see the children at work.

“Who can conjugate this in the past tense?” asks the teacher, writing the verb “to study” on the board. A volley of hands go up and, typically, she picks one of the kids whose hand stayed down.

We're told we can interview the children but from experience they invariably just recite revolutionary mantras under the watchful eye of their teachers. So instead I ask the head teacher herself what she says to critics, especially in Miami, who say that such heavy rhetoric at school amounts to indoctrination.

“It’s absurd to argue there’s brainwashing here,” says Elaine Infante. “Our revolution is very humanitarian and we think about the well-being of all children here.”

“That’s why we come to work. Not to turn them into militants, no. But to prepare them for the future, to make them into good men and women who can serve their society.”

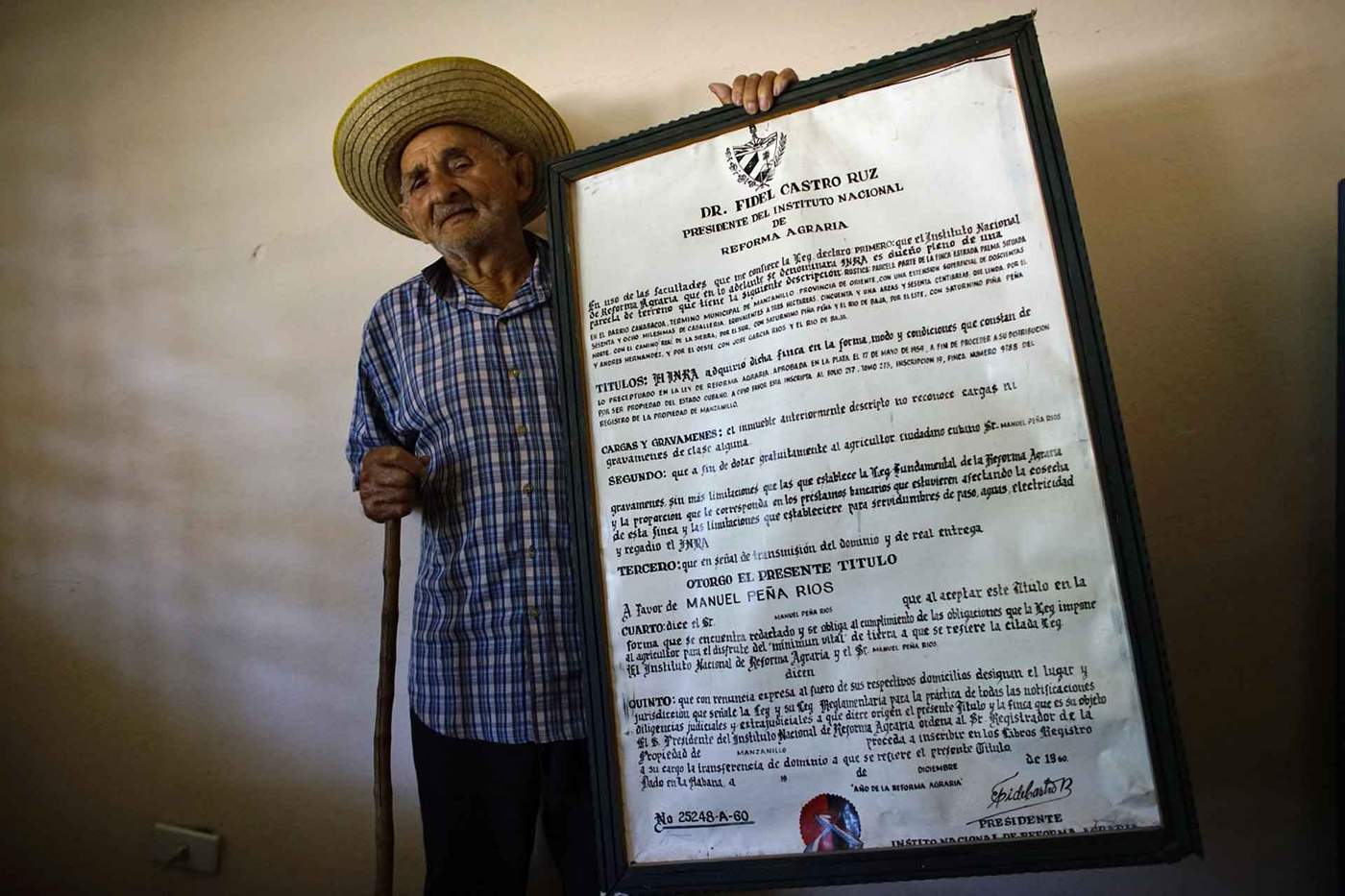

In the foothills of the Sierra Maestra the microclimate is perfect for growing coffee. At a point called Polo Norte - North Pole - lives Lérido Medina, another of the original recipients of the land titles. He doesn’t have the paperwork now, though - he donated his deeds to a museum in Havana.

Wearing a thick woollen shirt in the cool mountain air, the 92-year-old explains that he now relies on his wife, Aida, and his son to do the manual work on the farm.

“The hardest part has been cutting back the forest to sow,” says Lérido. “There is no mechanisation whatsoever, it’s all by hand – pickaxe, machete, brute force.”

The entirety of the family’s crop is sold to the state - coffee cannot be sold on the open market.

To this day, most farmers like Lérido see the agrarian reform as the bedrock law that gave them autonomy. But critics say it tied them to the state for life.

Lérido Medina

The economic rules have eased a little under Raúl's presidency and although they’re far from being private enterprises, the coffee farmers in Polo Norte joined forces to create a co-operative. It has allowed them to pool their resources and wield a little more collective bargaining power, explains Lérido's eldest son, Eziquiel.

But whether farming mountainous coffee plantations or the sugar cane and tobacco fields that dot the countryside, almost everyone involved in agriculture appears to agree on the limitations of the technology. Much of the farming equipment still used on the island is from the 19th Century - oxen and plough, horse and cart, machete.

“In the plains you can use tractors but not up here. It’s a tough life for the campesino but the work must be done,” says Lérido.

Despite Raúl's changes, the state-run model still forms the basis of Cuba’s agriculture. For many farmers, growth has been sluggish at best since the collapse of the Soviet Union and about three-quarters of Cuba’s domestic food requirements are imported.

However, hunger has largely been eradicated and it’s highly unlikely that a future leader would unpick one of the revolution’s founding principles in agricultural production.

While coffee is important to Cuba, sugar has traditionally been the island’s main export crop and at the centre of its economy.

On the road passing through Camaguey province, we stop to speak to a group of sugar cane farmers as they harvest the crop.

“We’re aiming for 40,000 tonnes this year,” says Osvany Iglesias, the leader of the harvest platoon, before echoing the complaint over working with Soviet-era machines.

“That was made in 1972, that one in 1975, and this is the most modern, from 1994,” he says pointing at the combine harvesters as they roar past. “The lack of parts is difficult and the Chinese replacements aren’t good quality.”

But he shrugs and laughs. There’s little choice but to make do.

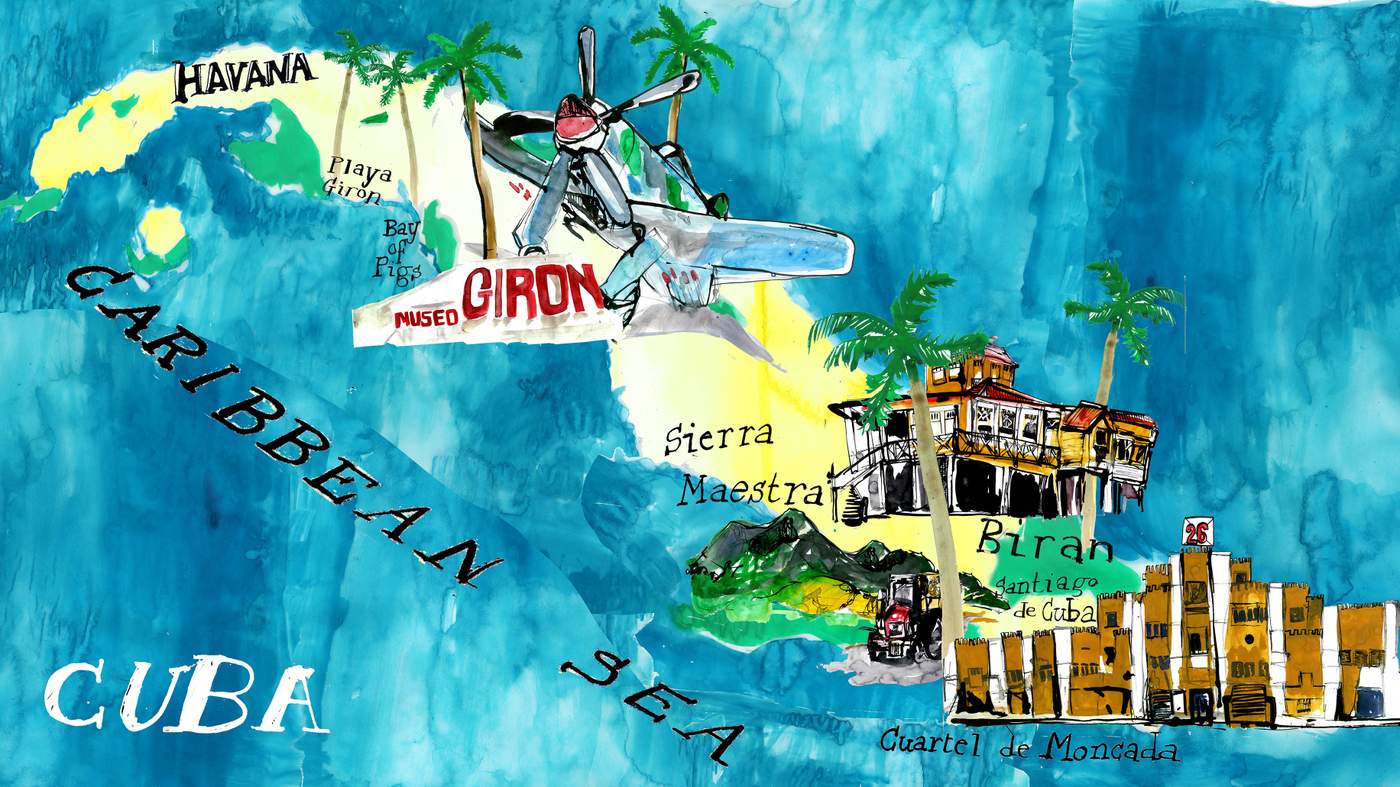

“GIRÓN: THE FIRST DEFEAT OF THE YANKEE IMPERIALISTS IN LATIN AMERICA” proclaims the sign at the side of the road as you drive into the town.

Revolutionary hyperbole aside, it is basically true. Washington had never really lost a battle in Latin America until the bungled invasion at the Bay of Pigs, or Playa Girón, in 1961.

For months, the CIA trained Cuban exiles in southern Florida and secret bases in Guatemala to prepare them for the invasion. On 15 April 1961, Douglas B-26 bombers with false flag markings attacked airfields outside Havana and in Santiago.

1961: Fighting during the unsuccessful US invasion at Bay of Pigs

Then came the invasion from the sea. Some 1,400 men came ashore at Girón and two other nearby beaches. It was a debacle from the start, with instructions going awry and the counter-revolutionaries getting lost and entangled in the harsh mangroves along the coast.

Fidel took control of the Cuban armed forces himself and, once Washington’s hand was revealed to be behind the attack, President John F Kennedy opted against sending in US air support.

The invasion was crushed, Castro had won a crucial victory and the Kennedy administration suffered a humiliating defeat. Che Guevara would later send Kennedy a thank you note for the invasion saying: “The revolution was weak. Now it is stronger than ever.”

That’s because there’s decent money to be made in the sleepy coastal village. As you drive into Girón, every other house has the distinctive blue-and-white symbol outside which denotes private accommodation where foreigners can stay. ‘Casas particulares’, as they are known in Cuba, have become one of the most popular private enterprises among ordinary Cubans.

Although the government has frozen the issuing of new business licences for almost a year now, tourist accommodation remains the easiest way for many Cuban families to break into the private sector, and earn much more than their state wages without having to invest a fortune to covert their homes.

Deynier Suarez, known as ‘Jimmy’, moved to Girón from the capital as the tourism boom in the area started to grow. He began as a chef in the state-run hotel near the beach but moved into the private sector when one of the most successful casa particulares in the town was looking for a manager.

“Business has been OK this year, but down on the previous two”, he explains. He attributes the downturn to two factors: Hurricane Irma, which wrought devastation on parts of Cuba’s northern coast. It left the southern coastline basically untouched but Jimmy thinks the television images of the storm gave the impression of chaos across Cuba and put off people from visiting.

Deynier “Jimmy” Suarez: Tourism has fallen because of Donald Trump

The other factor, he says, was Donald Trump.

“It’s been pretty noticeable”, he remarks of the stricter travel rules imposed by the Trump Administration following the warmer ties under the Obama presidency.

“Very few Americans are coming, you hardly see them. And Europeans, well, we hope they keep coming. We’re not worried yet but it would help if Trump changed his decisions.”

Beyond the revolutionary history, the average tourist comes to Girón for birdwatching or diving, with the Cienaga de Zapata National Park offering some of the best ecotourism on the island.

Just outside Girón is the Cueva de los Peces, a popular spot for diving and snorkelling.

Our instructor, Rey, takes us out to the largely undamaged reef. A group of Canadians enjoy investigating a sunken boat.

Two decades ago, Fidel essentially considered foreign tourists a necessary evil, a useful way of bringing in much-needed foreign currency.

Today, however, tourism has been earmarked as the solution for the island’s economic future and the government hopes for even more visitors in the coming years.

That has already brought some noticeable economic inequalities, a challenge the next president will have to bear in mind. There is a growing disconnection between Cubans who earn in the “convertible peso”, the currency used by most foreigners, and those who earn in the local “Cuban pesos”.

Some of those who work in state-run enterprises of the tourism sector are keen to spread their wings and set up their own businesses. Privately-owned diving shops, for example, are currently prohibited under the strict economic rules.

“There are a lot of us who are interested in going private,” insists Rey. “But things will stay the same for a while yet. This model suits the state.”

As the sun goes down it casts long shadows across the beach at the Bay of Pigs. Groups of tourists lounge under the palm trees, sipping on cold beers or drinking Cuban rum out of coconut husks sold by the locals.

Few looking on the scene can fail to reflect on the invasion of tourists - an obvious metaphor, but an accurate one. The question for the people of Girón is how much they will be allowed to harness it for their own ends.

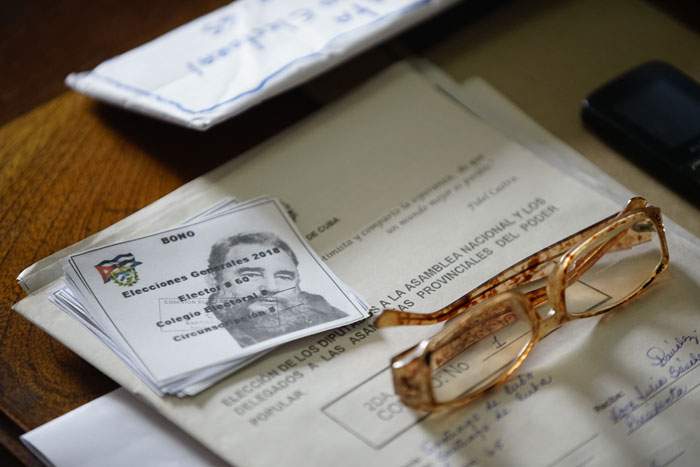

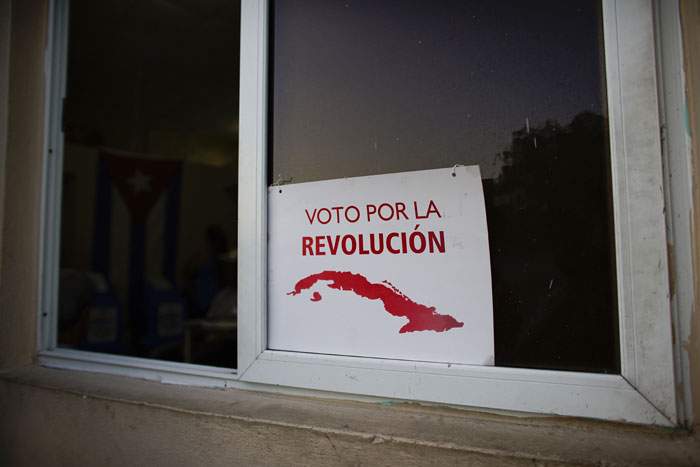

As Raúl was preparing to step down, Cuba held an election. Across the country, people dutifully turned out to cast their ballots for members of the national assembly.

On 19 April those national assembly members chose Miguel Díaz-Canel, the vice-president, to replace Raúl as president. In turns painted as a moderniser and a stalwart hardliner, he is the first non-Castro to govern the island since 1959.

Sounds straightforward enough. But in reality, on the ballots cast by Cuban voters there was exactly the same number of candidates as seats in parliament - 605. And, of course, under Cuba’s strict one-party system, no other choices of political colours were on offer.

Last year, a number of dissidents and opposition figures attempted to stand as municipal candidates, including members of a group called Otro 18. They claim they were prevented from registering their nominations through repressive tactics by the police and state security officers.

As I watched people vote, I was reminded of Raúl's comments in 2014. Barely five days after the historic agreement with President Obama to re-establish diplomatic ties, there was a genuine sense of expectation in the air.

Addressing parliament, Raúl quickly referred to the changing relationship with Washington saying: “We shouldn't expect that in order for relations to improve with the United States, Cuba is renouncing the ideas for which we have fought for more than a century and for which our people have spilled so much blood and run such great risks.”

The message was simple - political continuation. Open dissent or multi-party politics weren’t about to emerge in Cuba. They still aren’t.

A decade ago, the state’s modus operandi against its opponents and dissidents was to give them long jail sentences. Today, that practice has largely ended. In its place is a system of control under which critics and independent journalists are frequently held under short-term arbitrary detentions. For its part, the Cuban government accuses those critics of being “mercenaries” in the pay of anti-Castro groups from Washington and Miami.

Few can doubt that there were some on both sides of the Florida Straits who had their misgivings about improved relations between the US and Cuba. On the Miami side, the thaw was loudly decried by the standard-bearers for anti-Castro policy, in particular Florida Senator Marco Rubio.

On the Cuban side too, there were plenty of ideologues who were uncomfortable with the sight of the US president visiting Havana, the old enemy now playing nice on Cuban soil.

“I come to bury the remnants of the Cold War in the Americas,” said President Obama during his historic trip. He spoke of families - pulled apart by decades of hostility - being reunited amid a new spirit of friendship. “I just burst into tears,” one woman watching at home told me later.

2016: President Obama's visit to Cuba

Fidel wrote an editorial warning of President Obama’s “honeyed words” and asking revolutionaries not to let their guard down. A number of hard-line elements in the government strongly agreed with him and wanted to push back against the growing tide of pro-Americanism on the island.

Then, Donald Trump won the US presidency.

In the hours following Fidel's death, President-elect Trump took to Twitter to mark the passing of, as he put it, a “brutal dictator” whose “legacy is one of firing squads, theft, unimaginable suffering, poverty and the denial of fundamental human rights”.

The stage was set for a return to hostility. That is where things remain today.

The rapidly deteriorating relationship was then complicated further by a chapter straight out of a spy novel. More than 20 US diplomats in Havana began to suffer unexplained health problems, everything from hearing loss and nausea to mild concussion.

The State Department claims its embassy staff had been the victims of so-called “health attacks” and blamed Cuba for failing to protect the diplomats, if not necessarily carrying out the alleged acts.

Havana has denied any knowledge of the incidents and says the entire episode is a combination of cover story and mass hysteria. The intention was, they claimed, to undo the recent goodwill and justify a more hostile diplomatic and political relationship with the island.

Either way, the US drew down its staff in Havana to a bare minimum and today relations could barely be further from the heady years of thaw during the Obama administration. This is the context in which Raúl's replacement takes over the reins.

Does any of this matter to ordinary Cubans, like 92-year-old coffee grower Lérido, or Rey, the diving instructor who wants to open his own business?

One could argue very little. Certainly the most committed revolutionaries continually insist that everything will be fine. That the Cuban Revolution is in safe hands and that, in essence, everything will carry on as before.

It is undoubtedly true that no future government in Cuba would dare meddle with the key pillars of the revolution, especially the free healthcare and education or subsidies to the rural poor.

But when you ask how Cuba will pay for it in when its close socialist ally, Venezuela, is on its knees economically or when Cuba’s export earnings are low, you’re generally met with a smile and a shrug of the shoulders. Few can provide specifics on how the island will face the next set of economic challenges.

“We’ve been through worse. The collapse of the Soviet bloc and the ‘Special Period’,” one party official in Bayamo told me, referring to the economic hardships in Cuba of the 1990s. “If we can survive that, we can survive anything.”

This is where the blind trust in the system comes in, where true revolutionaries place their unwavering faith in the revolution to provide a solution. Under Fidel and Raúl, it was enough for many people.