Some guests were awoken by the gunshots, others by the buzzing of three Black Hawk helicopters.

It was the early hours of 16 July 2016. Around two-dozen Turkish commandos dropped into the grounds of the luxury Club Turban hotel in the coastal resort of Marmaris, armed with automatic rifles and grenades.

They were hunting one man - Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The president had been holidaying at a private villa linked to the hotel.

Tanks move through the streets of Ankara

While rebel soldiers in Istanbul and Ankara blocked roads and bombed state buildings, the commandos had been sent to capture the president. It should have been the climax of their coup d'etat. Opening fire and hurling grenades, they stormed the hotel, killing two bodyguards.

But they were too late.

Acting on a tip-off, Erdogan had been whisked away from the resort by helicopter. Once at Dalaman Airport, he took a private jet to Istanbul, with his pilot masking its identity so it appeared on radars as a normal civilian passenger plane.

After 03:00, the president emerged outside Istanbul's Ataturk Airport to the roars of his supporters.

The coup attempt had failed - and Recep Tayyip Erdogan was to emerge stronger than ever.

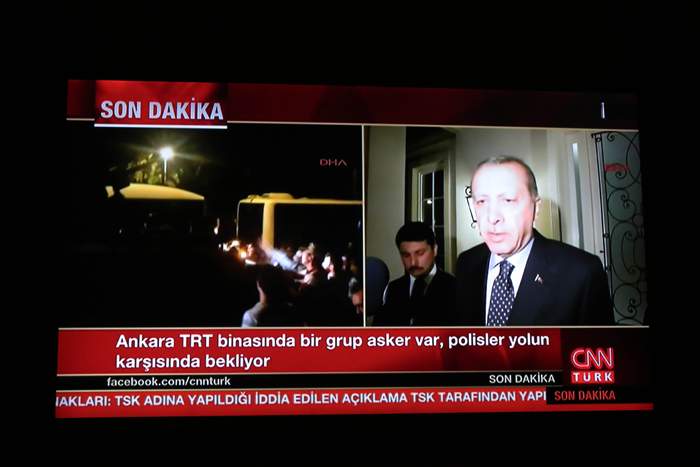

President Erdogan's message to the Turkish people

For many, that night marked the rebirth of modern Turkey. En route to Istanbul, Erdogan made a video-call to Turkish television, urging people on to the streets to resist the coup attempt.

Turks responded en masse - and 265 people were killed in the process.

Some lay in front of rebel tanks to block their advance, others ran into gunfire on the Bosphorus bridge, trying to overpower the coup plotters.

By dawn, the coup had failed.

For the first time since the foundation of the Turkish republic in 1923, the people had managed to stand up to the tanks. Over the decades, four coups had succeeded - Erdogan ensured a fifth did not.

Millions gathered in nightly rallies, chanting his name and singing his campaign song.

Erdogan went from almost losing control of his country to becoming untouchable.

But for Turkey's most powerful leader since its founding father, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, it wasn't enough. After 11 years as prime minister, Erdogan had been elected president in 2014.

The post was traditionally largely ceremonial but Erdogan had other ideas.

The dominant figure in Turkish politics had long dreamed of enshrining his authority through constitutional change, turning Turkey from a parliamentary to a presidential republic, scrapping the post of prime minister and consolidating his hold on the country.

On 16 April the Turkish people will decide in a referendum whether to accept his grand reform.

The president’s portrait stares down on Recep Tayyip Erdogan University in his family’s hometown of Rize, on Turkey’s Black Sea coast. Little says “personality cult” like naming an institution after a leader while he’s still alive.

Hatice Yildiz, 22, sits in the central courtyard. The wooden bench is embossed with Erdogan’s name, naturally.

Erdogan's hometown of Rize is 700 miles (1,100 km) east of Istanbul

“I’m proud of my president and I’m proud of my university’s name," says the English literature student. "He is really a good leader - a world leader.”

Founded in 2006, the university took the president’s name five years ago and now boasts 20,000 students. Its modern faculties are spread across Rize - a small, unremarkable city, the beautiful mountains surrounding it blighted by drab high-rise buildings.

The Recep Tayyip Erdogan University in Rize

The region is a heartland of Turkish nationalism - the conservative and religious side of Turkey that felt forgotten for decades and that found its saviour in Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Many here were ostracised by the old secular elite, who built up the Turkish Republic from its genesis in 1923 with the ideals of its founding father, Ataturk - westward-looking and fiercely secular, resisting the pull of the Islamic Middle East.

The Muslims of Anatolia often felt like second-class citizens, labelled “black Turks” as opposed to the bourgeois “white Turks”.

They were banned from wearing headscarves in public institutions - until Erdogan came along, a conservative Muslim himself, the first prime minister whose wife wore a headscarf. His government repealed the ban in 2013.

Hatice Yildiz

“My mother said it was really bad in her time,” says Yildiz, who herself wears a headscarf.

“Men could go to university but girls couldn’t, because they were covered. A person should be able to go anywhere they want - it shouldn’t be about their religion or their appearance.

“Before Recep Tayyip Erdogan, that’s what it was like. And he destroyed that law.”

Much of Erdogan’s support is underpinned by his championing of the Muslim cause.

In Rize, they love his piety - and of course, his local roots.

While Erdogan himself was born in Istanbul, he had strong family ties to Rize - his grandparents migrated there from Georgia and his father was born in the port city.

Standing by the giant mosque in Guneysu, the village adjoining Rize where Erdogan has a house, relative Sadullah Mutlu says he remembers the young Recep as “a mature boy, always ambitious and interested in politics”.

He wanted initially to become a professional footballer but was drawn towards the youth branch of an Islamist political movement. Soon after, he married Emine Gulbaran, with whom he has four children. His political rise was quick, becoming mayor of Istanbul, when he was briefly imprisoned under the secular regime for reciting a religious poem.

Erdogan’s working-class origins in the Black Sea and childhood in the poor Istanbul neighbourhood of Kasimpasa gave him his common touch and ability to connect with ordinary voters.

His supporters here feel he is their voice.

Erdogan's face on a building in Rize

Mehmet Meral is among them. Since the 1950s, his family has owned 140 acres of tea plantations in the mountains around Rize.

It is the centre of the country’s tea industry, with Turkey the world’s fifth largest producer. Terraced rows nestle beside fast-flowing streams and Ottoman-era stone bridges.

“Recep Tayyip Erdogan is one of us,” Meral says, “he’s one of the people. Before, all the leaders were rich kids or high class. He’s not like that.”

He speaks our language, gets aggressive like we do - and tells the world what we want to say”

That raw emotion is on show in the president’s rally in Rize, drumming up support for the constitutional referendum.

He holds the stage for an hour, enthralling thousands of supporters with talk of bringing back the death penalty for the coup-plotters and vaunting Turkey’s giant infrastructure projects.

Economic development is the other big driving force behind his support.

He also hits out at Europe, continuing a row after European leaders banned his ministers from campaigning among the Turkish diaspora in their countries.

“A few fascists will never destroy Turkey’s honour,” he proclaims, calling on Turks to “defy the grandchildren of Nazis” and back the constitutional change.

Such abrasive comments have infuriated Western governments but delight his fans, who wear headbands with his name and chant his campaign song.

The only other face on the giant flags is Ataturk - and Erdogan is now on the verge of eclipsing the republic’s greatest icon. The old secular ideals of Ataturk are virtually a distant memory in this side of Turkey.

As his speech ends, Erdogan and his ministers throw presents into the crowds - chess sets and children’s toys.

Outstretched hands clamber for the offering, a look of desperation in the faces of those for whom grasping the gift is second only to touching the great man.

And then Erdogan cuts a ribbon to symbolise the start of construction work on an airport in Rize - he has doubled the number of airports in Turkey in the past decade as his infrastructure drive ploughs on, helping win votes.

The reverence he commands is virtually unparalleled in the democratically elected world - “if he told me to die for him, I would” is a refrain you sometimes hear among his supporters.

It is a level of devotion matched only by the depth of hatred he inspires in the other side of this polarised country.

Istanbul's Gezi Park is a rare green space in the middle of a city choked by concrete. Next to Taksim Square, Istanbul's iconic heart, it is a haven of trees and grass amid the blaring car horns.

Gezi was never an award-winning park - but its importance was transformed overnight in 2013. As the government announced plans to redevelop it into a shopping mall, it became the symbol of another turning-point in Erdogan's leadership.

A few dozen environmentalists camped out in the park to show their disapproval. At dawn on 28 May, police moved in, burning down the tents and using tear gas.

It was the spark that lit the biggest street protests in Turkey's modern history.

The image of the Woman in Red was widely shared on social media

“It was empowering,” says Foti Benlisoy, a publisher and Gezi park protester. “We had the sense we were making history.”

Millions took to the streets across Turkey, spurred by the police violence but actually demonstrating about much more.

Erdogan, who had seemed like a pro-European reformer in his early years, was showing an increasingly authoritarian side.

The park itself turned into a giant carnival-like movement, similar to the Occupy protests elsewhere. Environmentalists were joined by leftist groups, Kurds, football fan clubs and a range of others. For a few days at least, the park hosted thousands of varied peaceful protesters.

But on Taksim Square, and across the country, clashes with police escalated fast.

Mark Lowen reporting on the Gezi Park/Taksim Square clashes

“It was a de facto coalition of grievances,” says Benlisoy.

“There was growing discomfort over the aggressive urban policies of the governing AK Party - over-building, commercialising common spaces, handing out tenders to Erdogan-friendly businessmen - with opposition from women's and LGBT movements, students and social rights groups.”

Conservatism was taking over - restrictions on alcohol sales and abortions were announced, and Erdogan had urged women to have more children.

Work had begun for Turkey's biggest mosque despite complaints that it was being built on protected forest land and would dominate Istanbul's skyline.

While some members of the government tried a more conciliatory approach to the protesters, Erdogan clamped down hard, labelling them “marauders” and accusing them of “drinking alcohol in a mosque” - something the mosque's imam then denied.

Early AKP rule under Erdogan reached out to democrats and liberals, leftists and Kurds, says Benlisoy. “But after Gezi his rhetoric became about the 'domination' of one side of Turkey towards the other, defining his support base by confrontation with the other.”

The polarisation deepened as Erdogan was shaken by leaks of phone conversations later in 2013 that appeared to implicate him and his inner circle in corruption allegations, which he fiercely denied.

He stoked the old Ottoman-era mentality of a Turkey under siege from its enemies, illustrated by the old adage “the only friend of a Turk is a Turk”.

There was a new conspiracy theory every week as the prime minister increasingly turned to arch-loyalists, while expelling or sidelining members of his own party who dared to dissent.

Freedom of expression was heavily squeezed. The progress of Erdogan's early years receded, as critical journalists, writers or artists were tarnished as “traitors”. Turkey regained its record as the world's leading jailer of journalists.

Erol Onderoglu is among the 150 journalists now in prison or facing trial.

A long-term representative of the watchdog Reporters Without Borders, Onderoglu attended an editorial meeting for a Kurdish paper, Ozgur Gundem, to mark World Press Freedom Day.

The government accused the newspaper of spreading Kurdish “terrorism propaganda” and closed it. The prosecutor is now asking for a 14-year sentence against Onderoglu.

For over a decade, we hoped that Turkey could belong to a European family... But then I found myself being handcuffed like an assassin.”

He spent 10 days in prison and faces trial in June. As he recounts the toughest moment, his voice breaks.

“When my wife and son came to visit me, I had to talk to them through the glass. That's when I realised what an injustice had been done to me.”

Dozens of media outlets have been closed since the failed coup, and journalists have been variously charged with “terrorism propaganda” or “insulting the president”.

Protest outside Cumhuriyet's office after editors were arrested

October 2016

Turkey's oldest mainstream newspaper, the secularist Cumhuriyet, has been raided and its editors arrested. Other critical voices have left the country or been jailed.

Erdogan claims Turkey has “the world's freest press”, while also stating those in prison are not journalists but “terrorists, thieves or child molesters”.

“Erdogan directly or indirectly controls 80% of the media in Turkey,” says Onderoglu, of the situation facing journalists.

“Any criticism of him is seen as criticism of the state. The definition of the job we do has been systematically eliminated from the Turkish dictionary.”

For Erdogan, extreme times justify extreme measures.

“There is no difference between a terrorist holding a gun or a bomb and those who use their pen and position to serve their aims,” he said, after Turkey’s worst ever terror attack, which killed 103 people outside Ankara train station in October 2015.

It heralded his crackdown - and dozens more attacks to come.

Aynur Yaman, an ethnic Kurd, knows the cost more than most. In her one-room house in a desperately poor village close to Diyarbakir, the biggest city in southeast Turkey, she now cares for her seven children alone.

Aynur Yaman

Her husband, Mehmet Salih Yaman, was killed last year when a truck blew up close to their home. It was believed to be carrying explosives belonging to the outlawed Kurdish militant group the PKK, possibly stockpiled for a future attack.

“They found his left finger and matched his DNA,” she says, “that’s all I remember - I had lost my mind.”

She glances up at his photo that she keeps on the wall. In the corner, her one year-old baby starts to cry. He had just been born when his father died.

“The PKK took away our dreams and stole a father of seven in the prime of his life,” 33-year-old Yaman says. “I don’t want to see their faces anymore. I will now vote for the people who have been supporting us psychologically and financially - for Erdogan.”

Close to 30 terror attacks in the past two years have killed about 500 people.

Kurdish militants were behind some - mainly targeting police officers and soldiers - while so-called Islamic State struck public areas, including Istanbul’s Ataturk airport and the city’s Reina nightclub last New Year’s Eve.

Turkey feels constantly on edge, awaiting the next attack - security is the biggest issue for many as they prepare to vote.

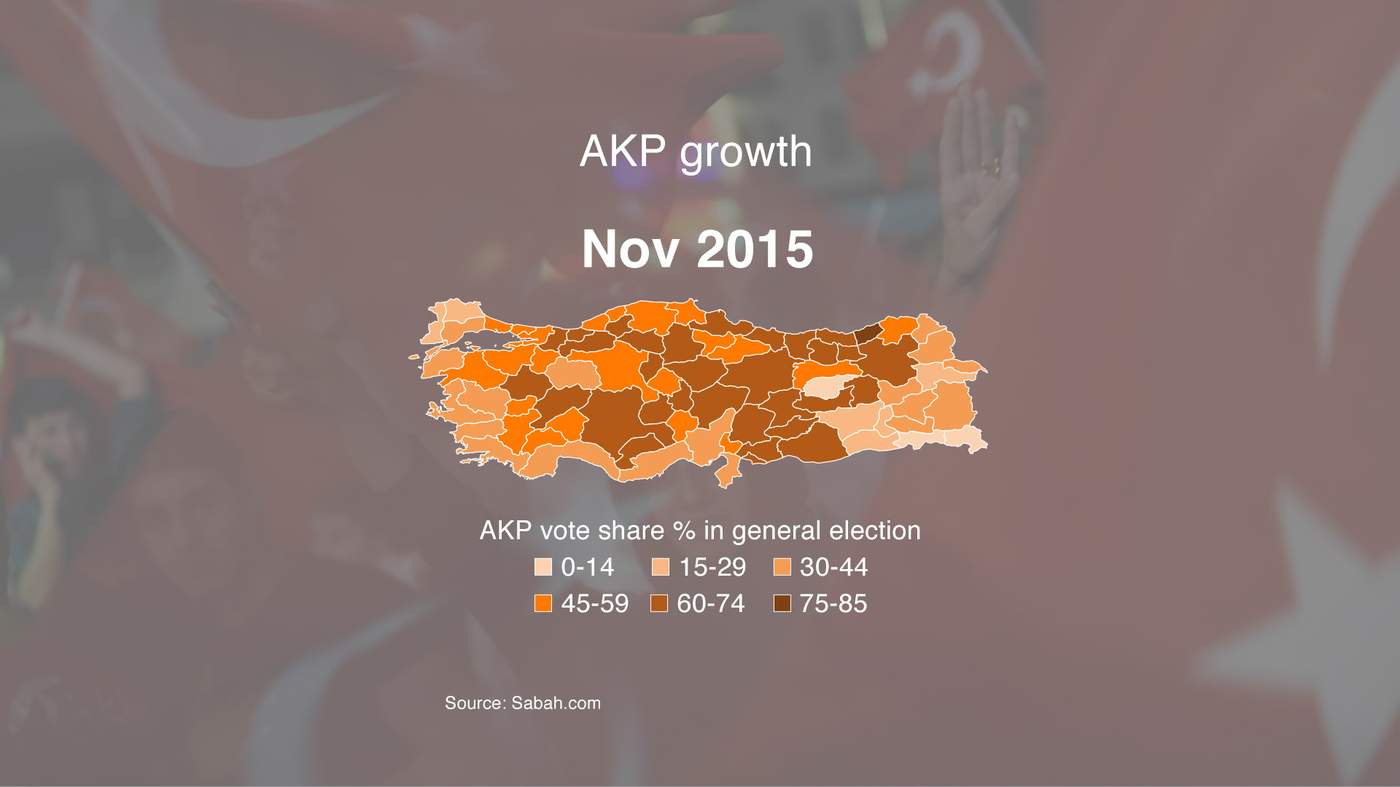

A ceasefire with the PKK broke down in July 2015, restarting a conflict that has killed 40,000 people since the 1980s.

Some blamed the militants for resuming armed attacks, others believe Erdogan engineered an end to the truce to whip up nationalist votes and regain the parliamentary majority he lost a month earlier.

If so, it worked - the AKP won back its majority in November 2015 and he’s hoping his hardline stance on terror will achieve victory in this referendum too.

Kurds clash with police in protest at curfews in Diyarbakir

December 2015

Large swathes of the southeast have seen curfews, military operations and urban warfare over the past two years.

The UN estimates 2,000 people have been killed - soldiers and civilians - while the Turkish army says it has eliminated thousands of militants.

The neighbourhood of central Diyarbakir where the worst of the fighting raged has been completely destroyed, with houses razed to the ground and surrounding buildings still torn by bullet holes.

Thirteen MPs from the pro-Kurdish HDP, which became the third-biggest party in parliament in 2015, have been imprisoned for alleged links to the PKK and 86 mayors have been replaced by the government.

Kurds who finally found a national political voice two years ago now feel silenced.

“The vast majority here think Erdogan and his people are responsible for the devastation that’s happened,” says Ziya Pir, an HDP MP who faces 23 years in prison for “terrorism propaganda” and “membership of a terrorist organisation”.

Bullet holes on a building in Diyarbakir

Kurdish voters are split between conservative Erdogan supporters and the HDP - but he is adamant over where the blame lies. “The old nationalist mentality of Turkey couldn’t allow Kurds to be partners in ruling the country - they had to kill it.”

He worries that hundreds of thousands in the southeast will be disenfranchised in the referendum after being displaced by the conflict and losing their voter registration. Now the only way to return to peace, he says, is with a “no” vote.

“With a ‘yes’, Erdogan would establish an authoritarian regime that may lead Turkey into a dictatorship. If it’s a ‘no’, Erdogan will see he can’t be genuinely successful without the help or votes of the Kurds. A ‘no’ would give a chance to return to negotiations to solve the Kurdish problem”.

AK Party office in Diyarbakir

Erdogan argues strong central leadership will give him the power to face down Turkey’s terror threats. But critics argue his government’s lax control of the border with Syria and support for Islamist factions has exposed Turkey to the IS threat and allowed jihadist cells to grow here.

Moreover, Ankara’s policy in Syria, attacking the Kurdish militia there, has made Turkey ever more vulnerable, provoking retaliatory strikes by the PKK.

Orhan Tokar was caught up in the terror attack on Kurdish supporters in Diyarbakir in June 2015, which was blamed on IS. He lost part of his left leg in the bombing.

An HDP supporter, his ire is directed mainly at the Turkish government.

“Erdogan can denounce me as a ‘terrorist’ or a ‘traitor to my country’ – my vote will always be ‘no’,” he says. “If ‘no’ wins, spring will arrive and people will be happy again. If it’s ‘yes’, the system will go back to Ottoman times, like a sultanate. And that will divide Turkey.”

After a year of terror attacks, Turks felt they had reached the bottom. But then came the coup.

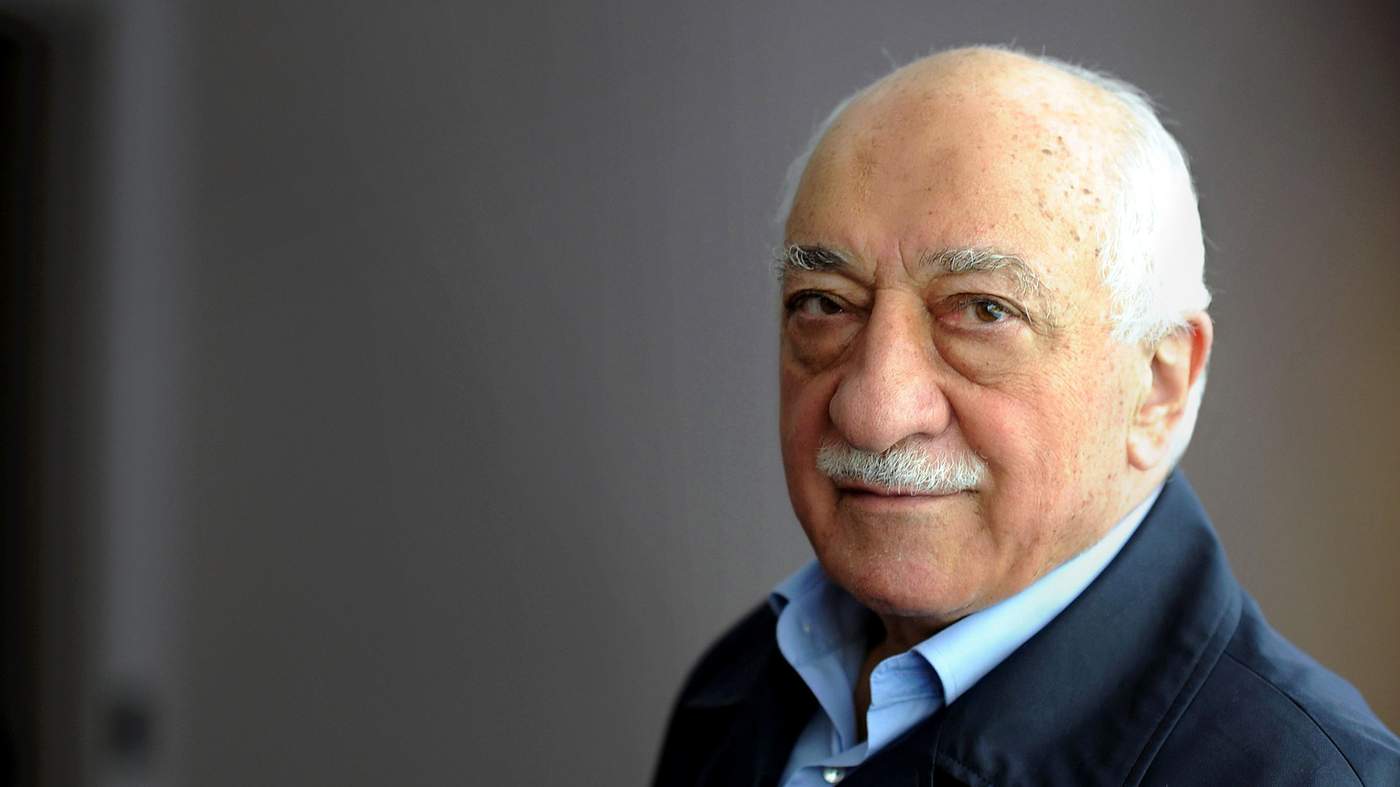

“The Gulen movement is a perfect definition of a cult,” says Said Alpsoy, sitting in his study surrounded by books on Islam.

A conservative researcher, he spent 17 years as a follower of Fethullah Gulen, the Islamic cleric who the government blames for orchestrating last year's failed coup.

“When Gulen was eating an orange, he threw the peel on the ground. I watched as one of his doctors grabbed the peel and ate it. I realised from the body-language that this was routine. The soles of his old shoes would even be boiled and eaten by his followers.”

Pro-Erdogan protesters hang an effigy of Gulen

July 2016

He seems embarrassed, apologising for the cruder examples he's about to give.

“Once, after Gulen gave an emotional sermon, he cried a lot and the handkerchief with which he cleaned his nose was wet. A young student took that handkerchief and cleaned his own face with it, right in front of me. Also, the stones of the olives that Gulen ate were never thrown away. They were distributed as valuable gifts to lower-grade people in the movement.”

Pupils at a Gulenist school in Turkey, 2008

Fethullah Gulen has built a network of followers since the 1960s, principally through schools and universities that he endowed in Turkey and across the world.

The group presents itself as a “faith-inspired, non-political, cultural and educational movement” adhering to “sympathy, compassion and altruism” through projects ranging from private schools to poverty aid programmes.

But followers ended up taking senior positions across Turkey’s public and private sectors, led by Gulen from self-imposed exile in the US.

“The movement never said in so many words 'let's take over the state',” says Said Alpsoy.

“Instead they would say: 'The state is taken over by the enemies of religion - let's get rid of these invaders and we will give it back to its real owners - the pious Muslims of Anatolia.'”

For years, Gulen was an ally of Erdogan, helping him cleanse the military of secularists.

But when the corruption scandal against the prime minister broke in 2013, Erdogan accused so-called Gulenists of tapping his phones and doctoring the evidence. Gulen became enemy number one, accused of leading a “parallel state”.

The government saw the putsch in 2016 as a vindication of its suspicions, blaming Gulen and his network and demanding his extradition from the US.

Foreign governments have cast doubt - the intelligence agencies of the EU and Germany have said they remain unconvinced that Gulen ordered the coup.

The UK's Foreign Affairs Committee found that while some Gulen followers may have been involved, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest the movement as a whole was behind it.

Turkey has so far failed to persuade Washington to extradite the cleric back to Turkey.

Fethullah Gulen in his study in the US

The shadow of the failed coup hangs over the current referendum battle, with Erdogan denouncing “no" voters as “siding with the coup-plotters" and a post-coup state of emergency limiting anti-Erdogan protests and making some reluctant to speak out.

It has also convulsed Turkish society through an ongoing purge of those suspected of siding with or backing the coup.

More than 160,000 people have been detained, dismissed or suspended - from police officers to pilots and teachers to businessmen.

Erdogan and his allies have painted a picture of enemies plotting against Turkey, but the purge has also now created a pool of victims willing to vote against him.

The president stands accused of purging opponents who had nothing to do with the coup. Hundreds of academics have been fired, including those who signed a petition last year calling on the government to cease its military operations in Kurdish areas of the country.

Erdogan lambasted them as “so-called intellectuals”, a “fifth column” of foreign powers and terrorists.

Oget Oktem Tanor is among them. Eighty-two years old, she was Turkey's first neuropsychologist and an emeritus professor of Istanbul University.

Now she has lost various rights she held as a civil servant and has been banned from travelling abroad, charged with “terrorism propaganda”.

Oget Oktem Tanor

“It's absurd,” the softly-spoken academic says.

“Of course I'm not helping terrorists. I just put my opinion into words by signing this petition. I have nothing to do with propaganda. Teaching and being with my students is my life, so it's very hard for me not to be with them again. For the first time, I felt depressed.”

She looks out to the Bosphorus from an apartment she's occupied for decades, as she built her reputation as one of Turkey's leading academics. After the coup of 1971, she was forced to flee the country with her husband, facing imprisonment and possible torture for being leftists.

“That time was still better than now,” she says, “because there was a judiciary you could trust and civil courts you could rely on. Now they are all under pressure and there's no separation of powers as there should be in a democracy. I really fear for the future of my country.”

Fear is felt on Istiklal Caddesi - or Independence Avenue - Istanbul’s main shopping street, which was until recently a symbol of the city’s vibrancy.

Hundreds of thousands of people thronged its cafes and shops each day, tourists riding the iconic rickety red tram past the foreign consulates and booksellers.

Today, it’s dotted with empty shops and bars, "for rent" signs filling spaces that would have been snapped up in days just a couple of years ago. Some avoid walking up the street entirely since a bomb exploded on it last year, killing four foreign tourists.

It’s a pattern repeated elsewhere. Leading foreign retailers, including C&A and Topshop, have pulled back from Turkey and the shopping malls that mushroomed in the past decade are no longer bustling.

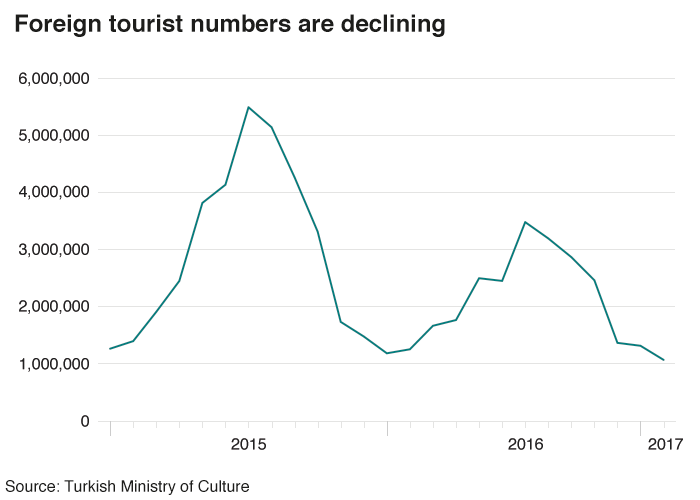

Tourism, which makes up around 10% of the Turkish economy, is declining rapidly. In 2014 Turkey was the world's sixth most-visited country - with 42 million tourists.

That dropped to 25 million in 2016 as Western tourists stayed away because of security fears. Hotels have slashed rates in an effort to bring them back.

Foreigners arriving in Turkey per month

January 2015 - February 2017

At Istanbul's Grand Bazaar, traditionally one of the world's most-visited tourist attractions, Erol Avci sits outside the carpet shop where he has worked for 39 years, desperate for custom.

“I started working here aged 18,” he says, “and this is the worst it's ever been. We're down by 80% and are not making any profit, so I'm not drawing a salary.”

His boss owns two of the shops they occupy - the third is rented and they're considering leaving it. Several others have already done so - empty shop-fronts now line some of the narrow lanes in this centuries-old maze of traders.

There's a creeping sense of financial crisis - a feeling that Turkey's good run has ended.

After a crash in 2001 that saw chronic inflation and the Turkish lira reaching an exchange rate of 1.5 million against the US dollar, Erdogan built a reputation for economic competence.

Growth soared to over 10% in 2011 and Turkey became known as the New Tiger, the fastest-growing economy in the G20 group of nations.

But terror attacks and political turbulence have led to the economy shrinking for the first time since 2009.

Unemployment is over 12%. The Turkish lira has lost a quarter of its value against the dollar since mid-2016.

“We are going through an economic crisis,” says Tekin Acar, whose chain of cosmetic stores is suffering. “Nobody is calling it that but sales are dropping, profits are falling and we will have to open smaller stores with fewer staff.”

This malaise could play out in the referendum. Ali Avci sips tea outside his ceramics shop in the Grand Bazaar, trying to pass the day. He and his family have always voted for Erdogan's AK Party - but now for the first time, they plan to defy him and say “no” in the referendum.

“This is a protest vote about the economy but also about Erdogan's lies, which we now see through social media,” he says.

“Days go by without any customers now. I could survive here if this goes on for another year but then I'd have to close. People are afraid of saying they're going to vote no - but lots will.”

It is a trend that appears to be gathering pace - some traditional AKP voters deserting the “yes” camp to voice their anger at the past two years of turbulence.

Opposition campaigners in Istanbul

Before the last general election, pro-government headlines screamed “AKP or chaos”. But even though the party won, chaos still came. And if Erdogan's once solid voter base begins to splinter, it could spell trouble for him in the referendum.

In the last week of the campaign, the governors of Istanbul and Ankara banned two large “no” rallies, claiming they couldn’t guarantee security. “Yes” rallies, however, went ahead – and free buses were provided to transport those who wanted to come.

On my 20-minute walk from my home to the BBC office in Istanbul, I counted 18 “yes” posters and one for “no”.

In some places “no” campaigners have been attacked and some people have been sacked for publicising their opposition.

Government supporters remain convinced that anti-Erdogan bias in the West is misconceived and point out that Turkey is - among other things - the world’s largest host of refugees.

It became the main route for those crossing to Europe, with thousands boarding dinghies every night from the Turkish coast to the Greek islands, and many drowning en route.

Turkey struck a deal with the EU to stem the flow - sending failed asylum seekers back. It’s widely believed that European leaders have tempered their criticism of Erdogan because they needed his co-operation on migrants.

But in some Western capitals, anger at Turkey’s unpredictable leader is growing. The European Parliament called for a suspension of EU membership negotiations.

In Turkey, this referendum will be a turning point. A “yes” would greatly strengthen Erdogan’s hand, giving him unprecedented power and possibly allowing him to remain in office until 2029, as well as virtually guaranteeing him and his family immunity from any attempts at prosecution.

A “no” would not spell the end for him - but would embolden the Turkish opposition and provide a chance for a political challenge.

Whichever way it goes, the chasm between Turkey and the West has grown dramatically.

Some blame Erdogan for that but others see the fault with the EU - that it had a window of opportunity after opening negotiations in 2005 to coax Erdogan into long-lasting reforms.

Instead, the argument goes, the EU gave way to the rhetoric of the likes of France’s Nicolas Sarkozy, who called Turkish membership “unthinkable”.

Turkey sensed it would continue to be held in the EU’s waiting room.

“Sadly, Europe sees President Erdogan and Turkey as an ‘other’ through which to deflect their internal problems onto a distant and imaginary enemy,” wrote Ibrahim Kalin, the president’s spokesman.

“It only deepens the sense of mistrust that is already poisoning relations between Turkey and Europe on the one hand and Islamic and Western societies on the other.”

Turkey matters. It remains a vital Western ally in the region, Nato’s eastern flank and a big trading partner. It is a crucial player in attempts to bring peace to Syria and the war against so-called Islamic State.

As it tries, with faltering success, to pivot more towards Russia and Gulf States, that could have a considerable geopolitical impact. The West cannot afford to lose this country.

“Democracy is like a train, Erdogan once famously said. “You get off once you have reached your destination.”

Some believe he has many stations left to pass, others that this country is in the midst of a slow-motion train crash. This could be the crowning moment or the undoing of Erdogan’s Turkey.