Warning: Depictions of drug use

Lisa used to be married. She had two jobs and was a mum to five kids. She calls it her normal life.

Now there’s only one thing on her mind. It’s all Lisa has been thinking about since she woke up.

Heroin.

Sitting in a friend’s house, she unwraps the foil carefully. “0.2g in weight, £10 in money,” she says, her eyes fixed on the brown powder. Reaching for a syringe, she wipes away a tear.

Staring straight at the heroin, she admits: “I put it before my children.”

We have no idea where Lisa got the money for her latest fix, or where she bought it from. We don’t ask.

In complete silence she unwraps the foil, reveals the brown powder, and gets the syringe ready. Next the injection - she’s breathing heavily as the heroin courses through her veins.

After a while, her eyes drop. She has a moment in her own world.

This is Lisa’s life. It’s the same routine day after day. And in a few hours, she’ll be searching for more.

Lisa calls it “rattling” - the feeling she has without heroin. “Legs aching, body sweating, hallucinations, diarrhoea, sick.” And in that moment what does she need more than anything?

“Brown powder to put everything right, automatic fix.”

The desperation never ends. Even with her prescription of methadone, which is supposed to be a longer-acting substitute for heroin, to help addicts stabilise, she still craves the real thing.

Lisa’s life has been this way for 12 years, on and off. She shakes her head as she describes the panic of waking up every morning addicted to heroin.

It controls everything. Being an addict is a full-time job

“I think, 'Where am I going to find the money today to score?' Money to get a bag [of heroin] to get myself better.”

“It controls everything, it controls every part of your day,” she says. “It is a disease, all of addiction is a disease.

“I said to the woman at the job centre I haven’t got time to get a job - being an addict is a full-time job. It’s ridiculous.”

As Lisa talks she looks down, mumbles. Her face is hollow, gaunt - the effects of years of addiction. She describes how she ended up here. She faced violence and, struggling to cope, she turned to alcohol, heroin, and then the final despair.

“I lost my oldest daughter and I’ve been on it ever since. I haven’t really dealt with her death - I’ve just buried my head in the sand.

“People that don’t know me might find it hard to believe that I had a normal life. I would want nothing more than to have a boring life again, just to wake up in the morning and have it all back.”

The place that Lisa calls home for tonight is a mess - the laminate flooring pulled up like scattered jigsaw pieces, plates with uneaten food left on the table.

Her friends get high in the kitchen. It’s mostly cannabis - one laughs and shows off about £10 worth. “There’s weed everywhere, a lot more [than cannabis] as well.”

They’re getting ready for a Friday night out. Some drink white wine, others smoke cannabis. There’s a fire burning in the back yard - thick black smoke billows, and there’s an overwhelming stench of burning rubber.

But in the middle of all this, there are signs of normality. A pet dog wanders, looking for attention, and heart-shaped family photos stare out from the mantelpiece.

Lisa now sofa-surfs. She’s staying with her best friend, but she wants something better.

“It’s not easy, it’s a fighting battle, it’s a stigma that goes with it all, it’s really hard to get that first foot in the door, to get the strength and support.”

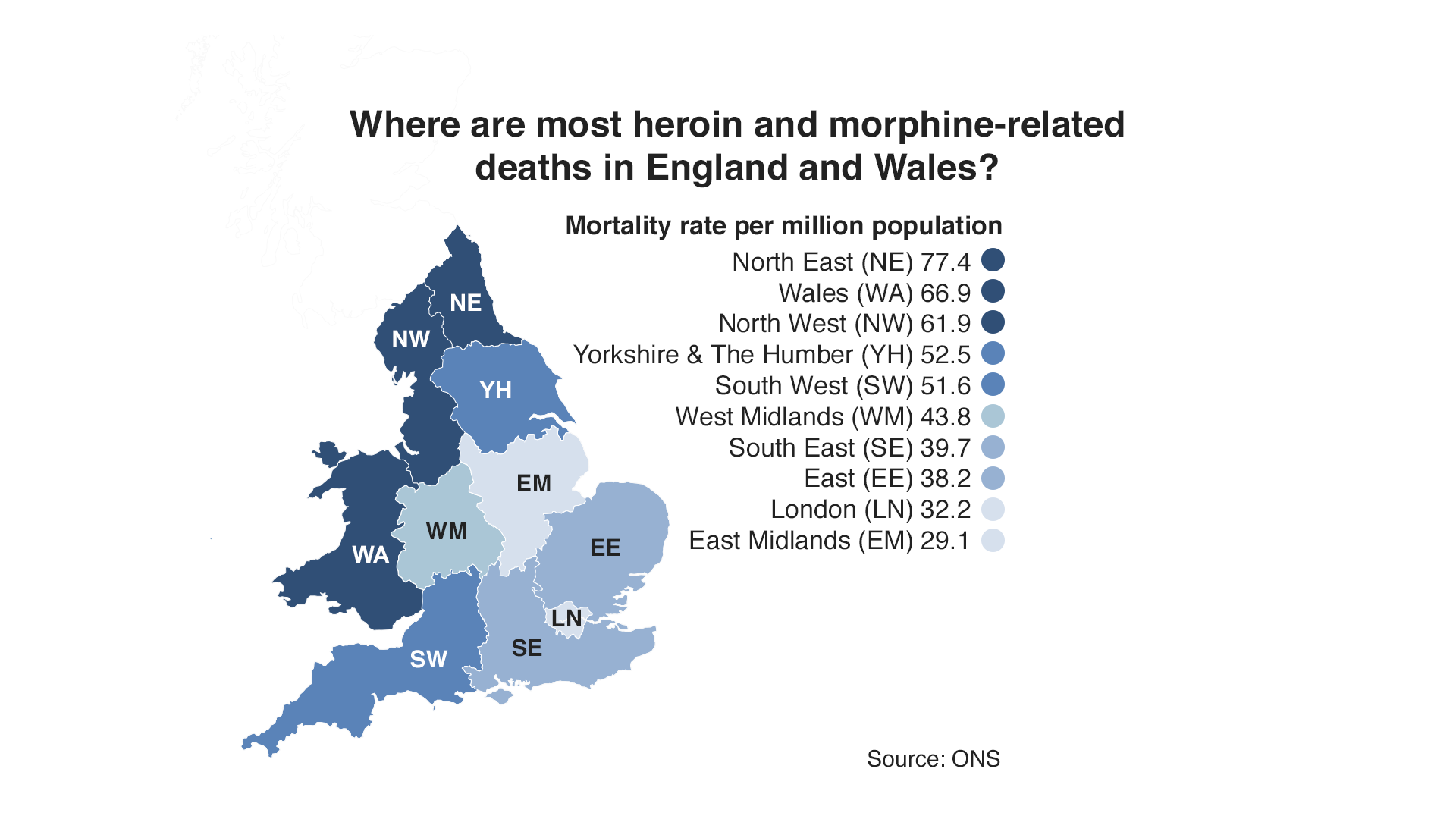

The North East, where Lisa lives, has the highest rate of death from drug misuse in England and Wales, but here radical change could be on the way.

County Durham’s police and crime commissioner has made tackling heroin addiction one of his priorities. Ron Hogg wants to bring in a form of heroin-assisted treatment - centres to give long-term addicts medical-grade heroin on prescription.

For some it’s highly controversial, but Lisa says it offers people like her hope.

She allows us to be with her and film while she’s shooting up. Why? Because she wants change, she wants people to see how addicts like her live and how they inject street drugs - without any idea of their purity or safety.

Heroin was the drug feared most in the 1980s. There was an epidemic. Remember Grange Hill and Zammo’s Just Say No campaign?

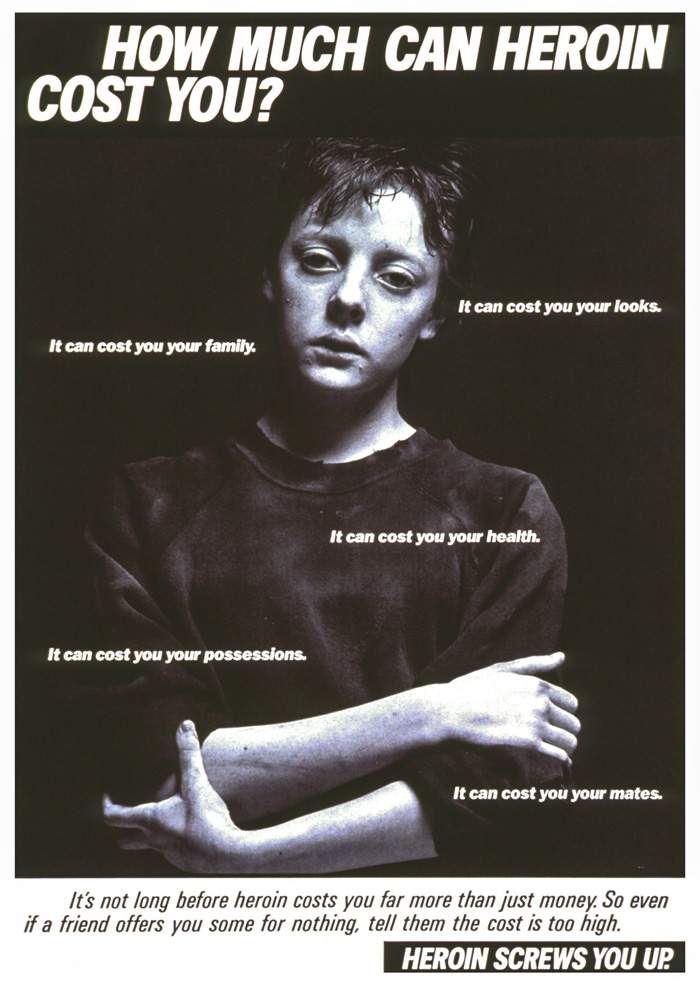

Adverts on TV warned that “heroin screws you up”, with young actors standing in dank, concrete stairwells and listing the dangers. Some now refer to the “Trainspotting generation” after Irvine Welsh’s story of addicts in Edinburgh.

A 1987 health education campaign on the dangers of heroin

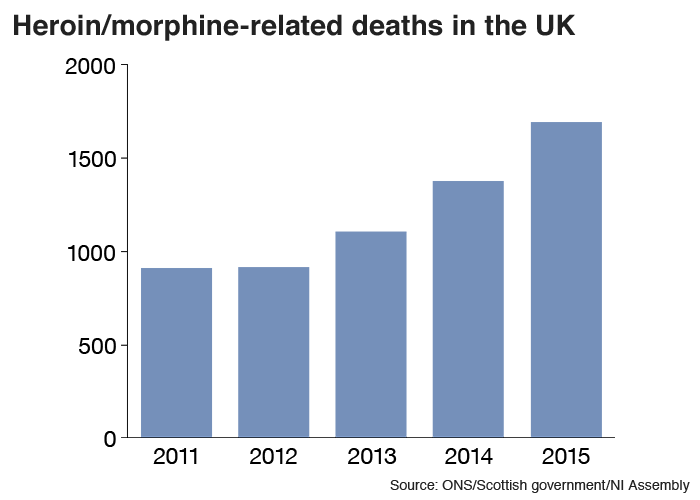

But now the number of deaths from heroin are at the highest level since comparable records began.

In the past five years death rates have doubled in England, Wales and Scotland.

On average in 2016, every five hours someone died after using heroin and/or morphine.

The government says the reasons behind the increase are complex and highlights an ageing population of heroin users who first started using in the 80s and 90s. These addicts are now more susceptible to overdoses after decades of physical and mental health conditions.

But critics point to the effect of budget cuts on treatment services.

Lisa is no stranger to death. In her small County Durham town she has lost many addicted friends over the years.

“There is loads, aye there’s loads… at least 20,” she says.

Lisa is typical of the kind of people who are at risk of dying from heroin overdoses. Long-term users in their late 30s, 40s and even 50s.

The problem north of the border is even more acute than in the North East.

According to National Records of Scotland, there were 473 deaths related to heroin or morphine in 2016 - more than double the figure from 2011.

Almost one in three drug overdoses in Europe happens in the UK, according to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction.

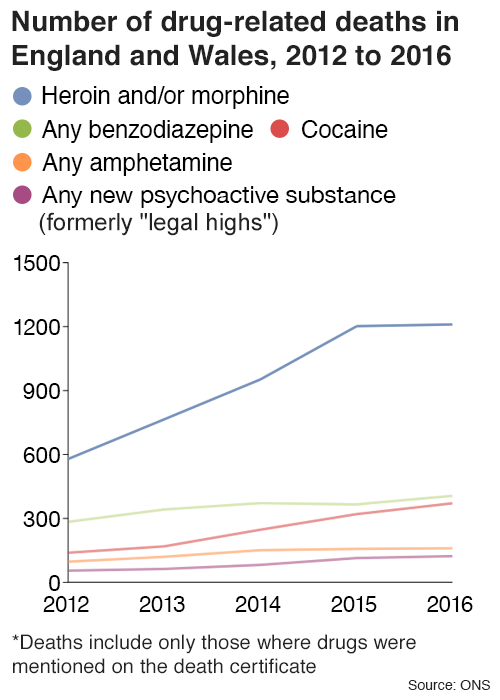

From 1993 to 2000, heroin and morphine deaths in England and Wales rose dramatically. Then they slowly declined.

But in 2010 death rates started to rise sharply again.

There has been a fundamental change in how drug treatment services are organised. Before 2012 they were jointly commissioned by the NHS and local authorities, but the Health and Social Care Act changed this.

The new law made local authorities solely responsible for commissioning drug treatment and their spending was no longer ring-fenced.

With reduced central government funding, councils were having to make savings across the board. That meant cuts.

The government’s Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) warned this year about funding of drug treatment falling.

The ACMD said if resources were spread too thinly, there could be increased levels of blood-borne viruses, drug-related deaths and drug-driven crime.

A lack of spending on drug treatment is short-sighted and a catalyst for disaster,” said Annette Dale-Perera, who chairs the ACMD’s Recovery Committee. “England had built a world class drug treatment system, with fast access to free, good quality drug treatment.”

The government says every drug overdose death is a tragedy and that it has made it easier for addicts to receive naloxone, a medicine that reverses the effects of a heroin overdose.

“Since 1 October 2015, a regulation came into force to make this life-saving medicine more widely available."

To feed her habit Lisa borrows money but she also steals. Admitting to being a notorious shoplifter, she says she used to be good at it.

Not any more.

Lisa is in a police station, arrested on suspicion of theft. The effects of heroin are long gone, the rattling about to begin.

How does she feel? “Sick,” she says, and she looks awful. How many times has she been arrested? “Over a hundred… for shoplifting, driving, possession.”

She is at her lowest, locked up in a cell, alone. She is later to be released without charge, but what is it she wants in her life more than anything else?

There is a long pause. She looks away before she answers.

“I want my kids back.”

But how can she when this is her life?

The Home Office estimates between a third and a half of all acquisitive crime is committed by offenders who use heroin, cocaine or crack cocaine. This covers crimes such as theft, burglary or shoplifting.

The cost of these crimes reverberate across communities - stolen property, insurance claims, courts costs, prison costs, it all mounts up.

Out on patrol with Durham police the pressures that drug-related crime causes are obvious. We meet Dawn Butler, whose son’s house has been broken into. She’s in shock.

“Walked in, noticed the fridge was gone, came into the kitchen, cooker gone, and the washer - which was practically brand new.”

All of the kitchen’s white goods have been cleaned out. There’s nothing left.

“They’ve broke in through the back door and they haven’t basically touched anything else. They’ve lifted eggs out of the fridge, the water out of the fridge. Turned the electrics off so they could take the cooker – that’s all they have taken. Nothing else.”

The next day we're on patrol with PC Martin Smith. His first job is to follow up on a suspected cable theft - metal that can be sold on quickly. The frustration is palpable.

“The majority of the people we deal with are repeat [offenders], all the time - whether it be thefts from shops or theft of metal and stuff from garden centres, stuff out of gardens, just to sell. It’s not high-value stuff, it’s just small, low-level crime to fund an addiction.”

The police take us into a house. It looks like a family home. On the surface all is well but look again and it’s littered with heroin paraphernalia.

“You can see there’s uncapped needles there. There’s signs that they’ve probably had the heroin in there.”

In every room PC Smith points out the signs of addiction.

“The needles have got blood inside them. Any infections that they’ve got, the kids prick themselves, you’re looking at anything from HIV, hepatitis, anything that’s transferable by blood.”

The officer picks up a school bag and empties it. It’s full of syringes and heroin "cooking pots". The police here are not shocked - they say it’s something they are dealing with day in, day out.

Statistics for England and Wales from the Ministry of Justice back up the officers’ frustrations.

In 2010-11, about 45,000 adult offenders were identified as drug users. Of these, about 26,000 re-offended within a year.

These re-offenders represented less than 5% of all adult offenders, but were responsible for 26% of all re-offences.

In short, addiction drives crime.

The average fix costs Lisa £10 and she says she can get it in minutes. She makes it sound as easy as popping out to a corner shop. The only problem is getting the cash - the drugs are easy to buy.

“You can get it from any back street in any colliery village.”

In County Durham, as in the rest of the UK, the chances are the heroin she’s taking right now will have made its way from Afghanistan.

A map of where discarded needles have been found - put together by the campaigning drugs charity Transform - clearly shows hotspots in towns and villages across the county. Many of them are former mining areas.

These are places where lives depended on the pits, but years after they closed, the communities are still in desperate need of new jobs and investment.

Much has been written about the link between deprivation, poverty, unemployment and the prevalence of drugs. Figures from the Office for National Statistics, showing deaths from drugs misuse for 2014-16, back this up. The top five areas in England and Wales are Blackpool, Neath/Port Talbot, Middlesbrough, Burnley, and Gosport.

The heroin that is coming to the UK is getting purer.

In 2016 the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) said that opium production in Afghanistan had increased by 43% over 12 months. With more land and better farming conditions, there’s more product for the international drugs market.

The charity Drugwise says that the heroin found on the streets of the UK in 2010 was considered to be low grade and had often been cut with other substances, such as paracetamol or caffeine. By 2014 the drug had reached 40% purity in some areas, while today purity levels are thought to occasionally be as high as 60%. This puts addicts at an increased risk of overdose.

Stopping the problem at source seems to be near impossible, but is there a more radical solution?

On a side street in Geneva stands an unremarkable looking building.

Chantal makes her way to reception, having taken the same journey hundreds of times before. An addict on and off for 30 years, she is 53 and is walking into the place where she is given heroin.

Chantal has been a heroin addict for 30 years

She stops at the window to chat to the nurse and to sign in.

“Bonjour, bonjour.”

How’s she feeling today? Everything OK? She heads down the corridor and into a room that has the feel of a dental surgery.

Along one wall, coloured plastic cups sit in rows on the shelves - the sort you’d find in a nursery. Each has a name on - Mario, Michel, Helene, Alfred... and Chantal. Hers holds everything she needs to prepare her daily fix of heroin.

Isabelle Guillaume is the nurse supporting Chantal today. She watches as Chantal starts her regular ritual. Washes her hands, takes a seat, pulls the desk lamp towards a chair, and sits down. She’s ready.

Lost in the job in hand, she moves her leg on to a stool and searches meticulously for the place that this afternoon’s needle will go.

With a click she secures a tourniquet below the knee and picks up the syringe of heroin that the nurse has placed there.

“Every patient has his or her dose of treatment,” says Dr Rita Manghi, deputy chief medical officer at the University Hospital of Geneva.

“The patient can say, 'Today the weather is hot, I take a little less,' or, 'It’s cold, I take a little bit more.' They have a capacity of how to determine what’s best for them.”

The first heroin-assisted treatment clinic opened in Switzerland in 1994. They are targeted at long-term users of heroin who’ve tried other forms of treatment, such as methadone, that have not been successful.

The philosophy is based around addiction being an illness that needs treating.

Chantal first took heroin when she was 20.

“The worst thing was to see people who I loved, suffer and to give pain to my family. They see me being destroyed. But it was my choice.

“My mother does a lot. She gives me money. I have a fantastic mother who I never need to lie to because she understands everything.”

But Chantal says her 10-year-old daughter doesn’t know that her mother is addicted to heroin. The girl lives with her father. Chantal says this is hard but for the best. She has been close to death sometimes after overdosing.

“Four or five times. Once there was a doctor who said to my mother – I was dead.”

Chantal says the clinic has given her stability, allowing her to rebuild her life, and see her daughter regularly.

The opening of heroin-assisted treatment clinics has reduced crime and the amount of illegal drugs on the streets on Switzerland.

“It’s a big change because they don’t have to look for drugs, they know that they are here and that we are nurses and doctors and we take care of them,” says Ms Guillaume.

“They can begin to think of something else other than having drugs and having money for drugs. They begin to think, 'What can I do for my life?' We talk together and they have to work out a new life.”

Chantal cleans her leg thoroughly before finding a spot near her ankle - where she carefully puts in the sterile needle.

At first it doesn’t work - blood fills the needle but there is no sense of panic. Isabelle smiles, provides a clean syringe and Chantal begins again and finally injects the heroin.

Within minutes Chantal is finished and the next addict is waiting. Chantal wipes down the table, disposes of the syringe and returns her pink plastic beaker to the shelf. It’s business as usual.

“Against this treatment, people say if we give heroin to them, they will ask [for] more and more and more,” says Dr Manghi.

“This is not true, they generally ask [for] less. Because it’s always the same substance, it’s pure.”

As she leaves the clinic, Chantal speaks of her hopes for the future - to live with her daughter and to have a play she’s written performed in a theatre.

Dr Manghi says that the priority here is not to get addicts off heroin but to stabilise their lives. This kind of treatment is controversial, but the staff are adamant about the benefits.

“Every morning that I come here I know I help," says the nurse. "I know that I don’t only give heroin – we give life.”

Durham’s Police and Crime Commissioner, Ron Hogg, has been to Switzerland to see the heroin clinics for himself.

“I’m very impressed. The treatment is delivered in a very safe manner. They always have more than one member of staff available - it’s vitally important for the safety of the patient and for the staff.”

It’s estimated the Swiss heroin clinics costs about £15,000 per year per patient, but the programme’s supporters say that is more than matched by savings across health, criminal justice and other services.

They also mitigate the risk of overdose - the addicts are taking controlled doses in controlled conditions with medical professionals present.

Mr Hogg wants the same for County Durham. A way of reducing deaths, and reducing some of the chaos addicts create in the wider community.

Durham Police and Crime Commissioner Ron Hogg wants heroin-assisted treatment clinics in the UK

He believes rising drug deaths show that the UK has failed to deal with a growing crisis.

“The whole strategy - the national strategy, the legislation, the whole approach - is what has failed.”

Mr Hogg is the first police and crime commissioner to call for heroin-assisted treatment to be part-funded by the police. He knows it will be controversial.

When it has been floated before there has been staunch opposition. Trials in the UK in 2009 were criticised by campaigners Europe Against Drugs. “This perpetuates addicts' maintenance on the drug when the goal should always be abstinence,” said the group’s vice-president Mary Brett.

Treatment means the goal should be people get off drugs... You don't give people poison to make them better.”

And there has been opposition in Switzerland too. Before a referendum on the policy in 2008, Sabine Geissbuhler, of the Parents Against Drugs group, said it was ludicrous to think of the programme being “treatment”.

“Treatment means the goal should be people get off drugs eventually - they stop being addicts - and that's just not happening. It's an outrage that the state should give addicts heroin - it's poison. You don't give people poison to make them better.”

There would be similar opposition in the UK today, but Mr Hogg is undeterred.

Before his election as PCC, he was a police officer - he says he’s dealt with victims of fatal heroin overdoses, and has had enough of the never-ending cycle.

“The first thing is to decriminalise personal use of all drugs.” This would allow a “medical solution” for the problem, he says, citing the example of Portugal where drugs were effectively decriminalised in 2001. “We’re seeing a reduction in drug use and we’re seeing a reduction in cash going to organised crime groups.”

But why should the state pay for free heroin for addicts?

“I don’t hear any outcry about people getting nicotine patches, but it’s a health problem, I don’t hear criticism for people getting help for their alcoholism, it’s a health problem. The policies we’ve adopted so far haven’t worked and we need to radically change those and I will work radically to change that.

“Some people would say that they chose this kind of lifestyle. Actually they do not – the drug chooses you. It’s a disease – we need to treat it medically.”

The government recently ruled out any plans to decriminalise drugs, saying that the medical evidence showed people’s mental and physical health were harmed by illegal drugs.

But it does seem to be more open-minded towards heroin-assisted treatment or “prescribed diamorphine” as the Home Office calls it.

“[We] recognise the potential of prescribed diamorphine in helping people to recover. There is evidence from the UK, and other countries, that supervised use of this in a medical environment as part of a treatment plan can help keep patients in treatment and out of criminal behaviour.”

The UK has arguably been here before with a system of legally prescribing heroin in place until the 1960s.

Mr Hogg believes the facts and figures now back him up, and that as well as preventing deaths there would be a wider benefit to the community.

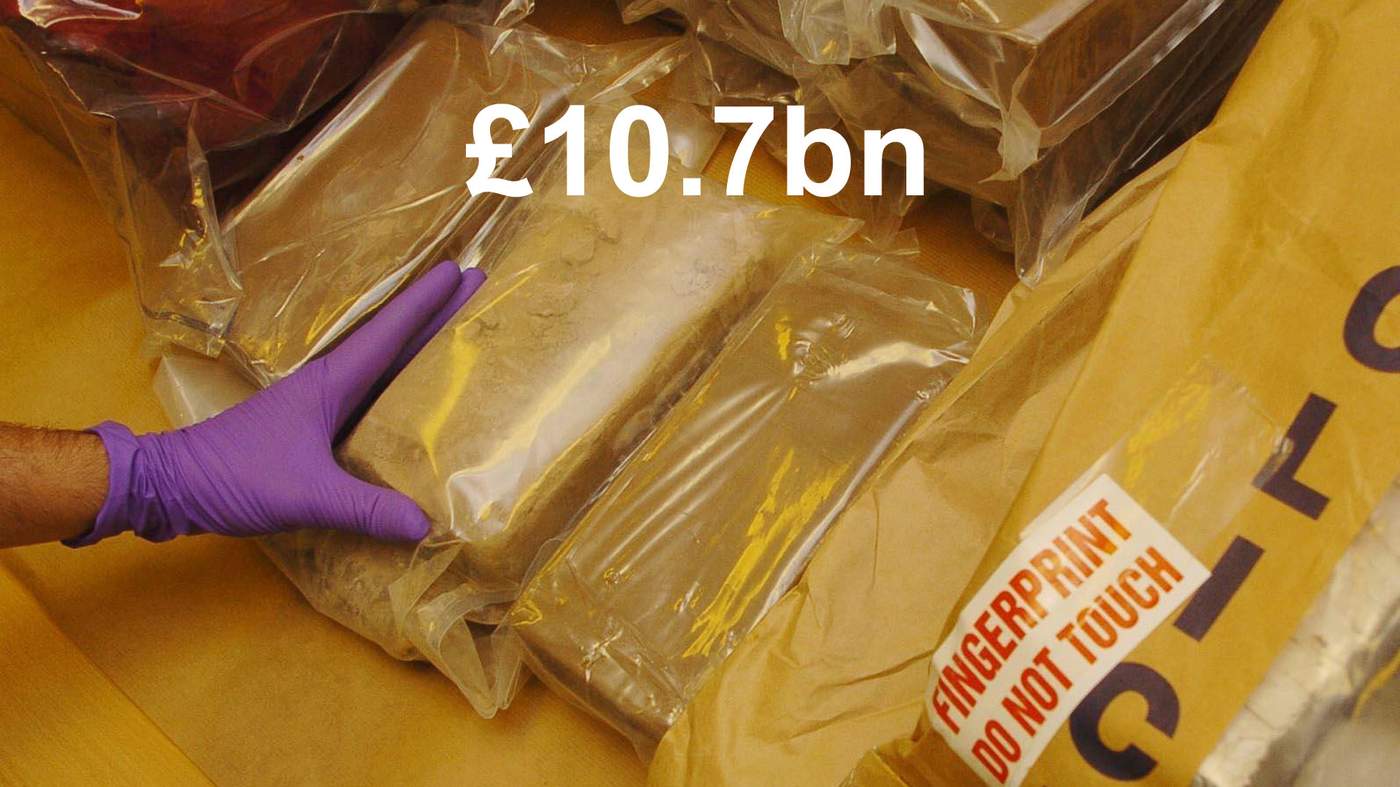

Any heroin or crack addict not in a treatment programme commits crime costing an average of £26,000 a year, according to Public Health England.

The annual cost in England of looking after children of drug-addicted parents is more than £42m. The cost of drug misuse to the NHS in England is £488m every year.

In Switzerland, heroin-assisted treatment has been credited with reducing burglaries by half.

And the programme has deprived criminal gangs of funds as users stop buying illicit heroin for themselves.

Four police and crime commissioners, including Mr Hogg, have told the BBC that in the right circumstances, they would be in favour of decriminalising illegal drugs including heroin.

Seven PCCs have said they would consider or support heroin-assisted treatment. The Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, has said heroin treatment centres could be another tool in providing support for users.

The government says that since funding decisions for drug treatment are now made by local authorities, the power lies with them to find the best ways of helping addicts.

Change might come first in Scotland. Glasgow Health and Social Care Partnership has said plans for heroin-assisted treatment have been confirmed in principle.

They also want to provide what’s called a consumption room or safe injecting facility (SIF), a place where addicts can bring their own street heroin and inject safely. The Home Office opposes this, saying SIFs are likely to lead to a range of criminal offences being committed and that they are costly to run and divert money away from better treatment options.

There is small but growing support for heroin-assisted treatment clinics among local politicians and PCCs across the UK but with the potential controversy, it seems many are waiting for someone else to set up the first permanent programme.

Despite the government’s supportive tone, many politicians are wary, worried about the headlines. And they will have to find the money themselves at a local level out of stretched budgets. It takes a big financial commitment to set up a heroin clinic. The proposals in Durham are yet to go before the council for a decision.

So Lisa carries on with her street heroin. The only constant in her life is her addiction. Her previous life, she says, is a blur.

“I don’t know who that person is now,” she says. The heroin is in control. “I’m not the same person I was.”

On our final day with her, Lisa is feeling positive. She hopes her part of County Durham will get a heroin treatment centre sooner rather than later.

We spoke to addicts in Durham who thought heroin-assisted treatment wouldn’t work for them and feared it would prolong their addiction. But Lisa believes it would give her a second chance.

“It would mean everything. I could actually start living again without having to start running about like a headless chicken to try and sort my day out. By the time I do get sorted, it’s time to start all over again. That’s all every day consists of, there’s nothing else.”

We leave Lisa as she walks into town to pick up fresh needles and syringes for her next hit. She’ll soon be shooting up alone, risking everything for heroin.