This is the story of how the pressure of debt drove a boy to take his own life.

In February 2015 Jerome gets a new job at CitySprint, a company that hires couriers to carry out individual deliveries.

His job is to bike around London transporting blood and documents between the city's hospitals - which are dotted all over the capital.

He's excited to finally get some financial independence. Although he's worked as a takeaway delivery boy before, the hours were really anti-social and he didn't make very much. Plus, he already has a motorbike - which makes getting the courier job much easier.

Delivering supplies to hospitals is an important job, and Jerome needs to be able to get across the city as quickly as possible.

When he first gets the job, Jerome excitedly tells his friends that he could earn as much as £1,500 a month - because he's technically "self-employed".

What this means is that Jerome isn't classed as a "worker" or an "employee" of CitySprint. He's technically, legally, in charge of his own earnings.

It also means that he isn't guaranteed a minimum amount of work in any given week, and he doesn't have any set hours.

But Jerome needs to keep himself available for as much of the day as possible. When he's logged in to the system, CitySprint could ask him to take a job at any time - and if he's not ready, he'll lose out on the job and any money he could have earned doing it.

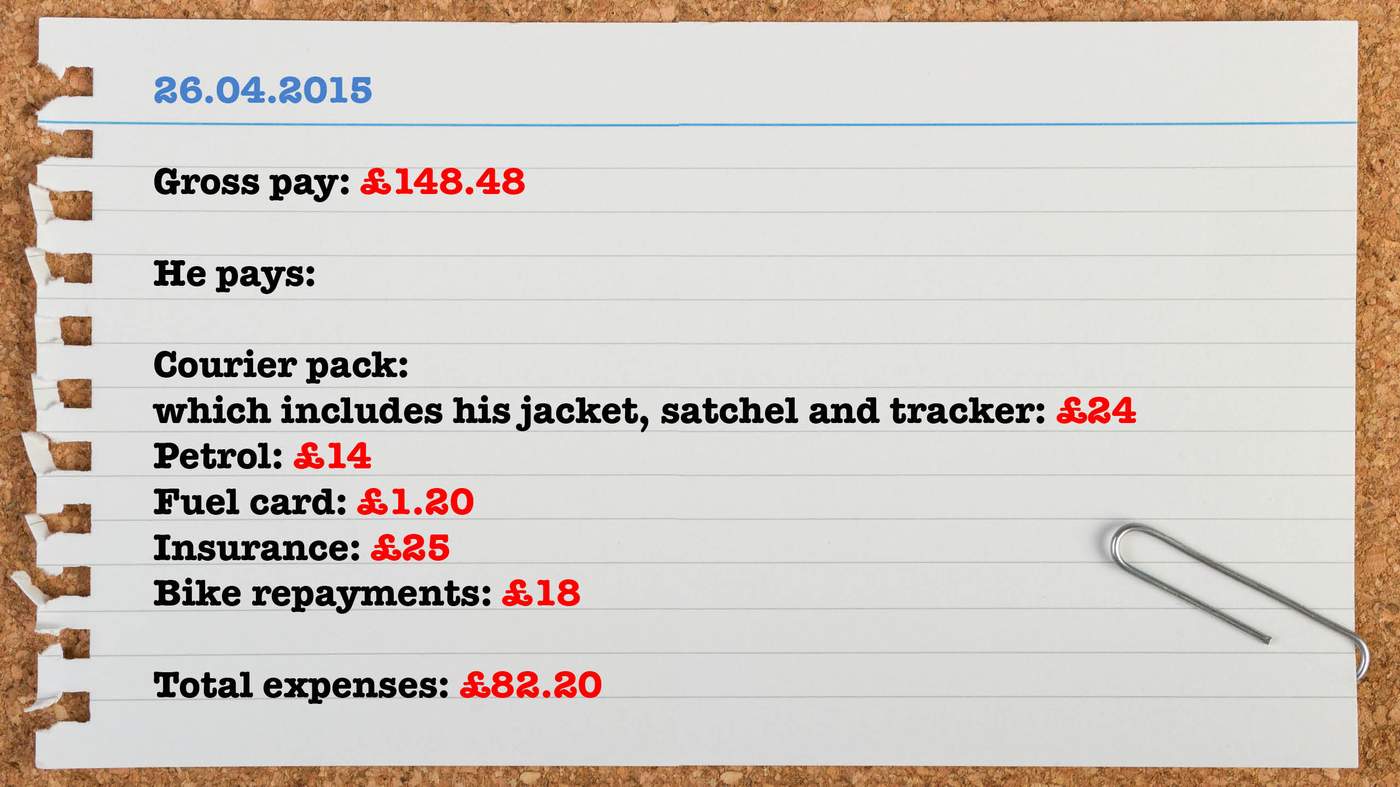

Plus, because he's technically his own "business", he's responsible for all of his expenses - including the cost of his bike, his petrol, and any traffic fines he might get while out on a courier job.

He also has to pay CitySprint fees in order to hire his uniform and communication devices from them.

Still, Jerome is excited. He thinks he can make good money as long as he keeps himself available.

It's his first real job and his mum is proud of him.

But there's a problem - his bike won't start.

JEROME'S BIKE BREAKS DOWN

He can't fix it himself.

He's a courier and needs his bike to take jobs. No working bike means no money - and if it's out of action for too long, the company might stop sending work to him altogether.

After seeing Jerome in despair, trying and failing to fix the bike in their driveway at home, Bentley offers to buy him a replacement.

The family go to a bike dealership to see if they can get a good deal on a second-hand model, but a bright red bike catches Jerome's eye.

The bike is perfect but there's a catch - it's brand new.

Watching the family, a salesman intervenes and tells Bentley that he can sell him the brand new bike on a zero-interest payment plan.

This, the salesman claims, will work out cheaper than buying a second-hand model on credit.

Bentley is a chauffeur, and is already paying off his car and Tracey's car. But knowing how much Jerome needs the bike for work, he agrees.

Jerome promises to pay him back in instalments - which works out at £73 a month.

But Jerome isn't worried about paying it off. All he has to do is work a few extra hours and he reckons he'll easily cover it.

What is the 'gig economy'?

As a self-employed courier, Jerome is now one of many young people working in the "gig economy".

The gig economy is where people take on short-term or freelance work instead of permanent jobs. These include private-hire cab drivers, food delivery workers, and couriers.

But with the gig economy booming in cities like London, working conditions are becoming increasingly unstable.

There are now 4.8 million self-employed people in the UK - although past studies by the Citizens Advice Bureau (CAB) have estimated that around 10% of this "self-employment" isn't genuine.

That is, companies are classing people as self-employed, meaning they miss out on basic protections like holiday pay and sick pay, even though they are carrying out the work of employees or full-time workers.

As of April 2018, there are also 1.8 million people in the UK on zero-hours contracts - another notoriously unstable form of work.

People in "bogus" self-employment, on zero-hours or short-hours contracts have to deal with erratic shifts and pay, and little work-life balance.

They could be working full-time one week, but only a few hours the next. Their shifts are impossible to predict, and their weekly earnings can vary significantly.

Zero-hours workers are entitled to paid annual leave and the minimum wage, just like those on more traditional fixed-hours contracts - although half of zero-hours workers are said to be unaware of these rights.

Self-employed contractors like Jerome, however, are not entitled to any statutory rights.

Jerome is also not paid unless he's carrying a packet at that moment. So the time he spends travelling to a hospital before picking up a package is essentially unpaid.

And because the distance he travels is different depending on what job he takes on, his pay fluctuates wildly too.

Usually the assignments he takes on get him about £3 to £6 each time.

Jerome has only just brought home enough money to pay off his £65 traffic fine from Camden Council - but if he pays it off, he'll have no money left for the rest of the week.

He puts the council's letter to one side, hoping to sort it out later.

Before Jerome can pay off his first fine, he has been given a second one.

He is still paid less than £10 for most of the deliveries that he's doing - which makes it hard to tackle the fines.

On 28 September, Jerome receives a "notice of enforcement" from Newlyn PLC, a private bailiff company hired by Camden Council to recover unpaid money.

One of Jerome's fines has more than trebled to £202, with another £75 "compliance fee" - a fee added by bailiffs - on top.

As the weather gets colder, Jerome's asthma is worsening - making it even harder for him to work enough shifts to take home a decent pay.

As his debts grow, his health steadily declines - and so does his pay.

Less than a month later, in October, he receives a "removal of goods notice" from Newlyn telling him that he now owes £512.

Jerome faces having someone come to his house and take away his belongings if he doesn't pay the newly increased fine.

20.11.2015

In November 2015, Jerome receives a letter telling him that he's been given "final notice" before they remove his goods.

An Enforcement Agent will be attending your property within the next few days to remove your goods to settle your outstanding debt. TELEPHONE 01604 ------ IMMEDIATELY TO DISCUSS PAYMENT.

Jerome's debt has now skyrocketed to £789 - an amount he can't possibly hope to repay.

On 10 December, Jerome gets a letter headed:

REMOVAL OF GOODS NOTICE

It says: "Our REMOVAL UNIT is currently operating in CR0 and will be looking to remove your car & household possessions. TELEPHONE 01604 ------ IMMEDIATELY TO DISCUSS PAYMENT."

Jerome's debt has now soared to £1,019. Including the £5 he managed to pay off last month, his debt has increased by £822 in less than four months.

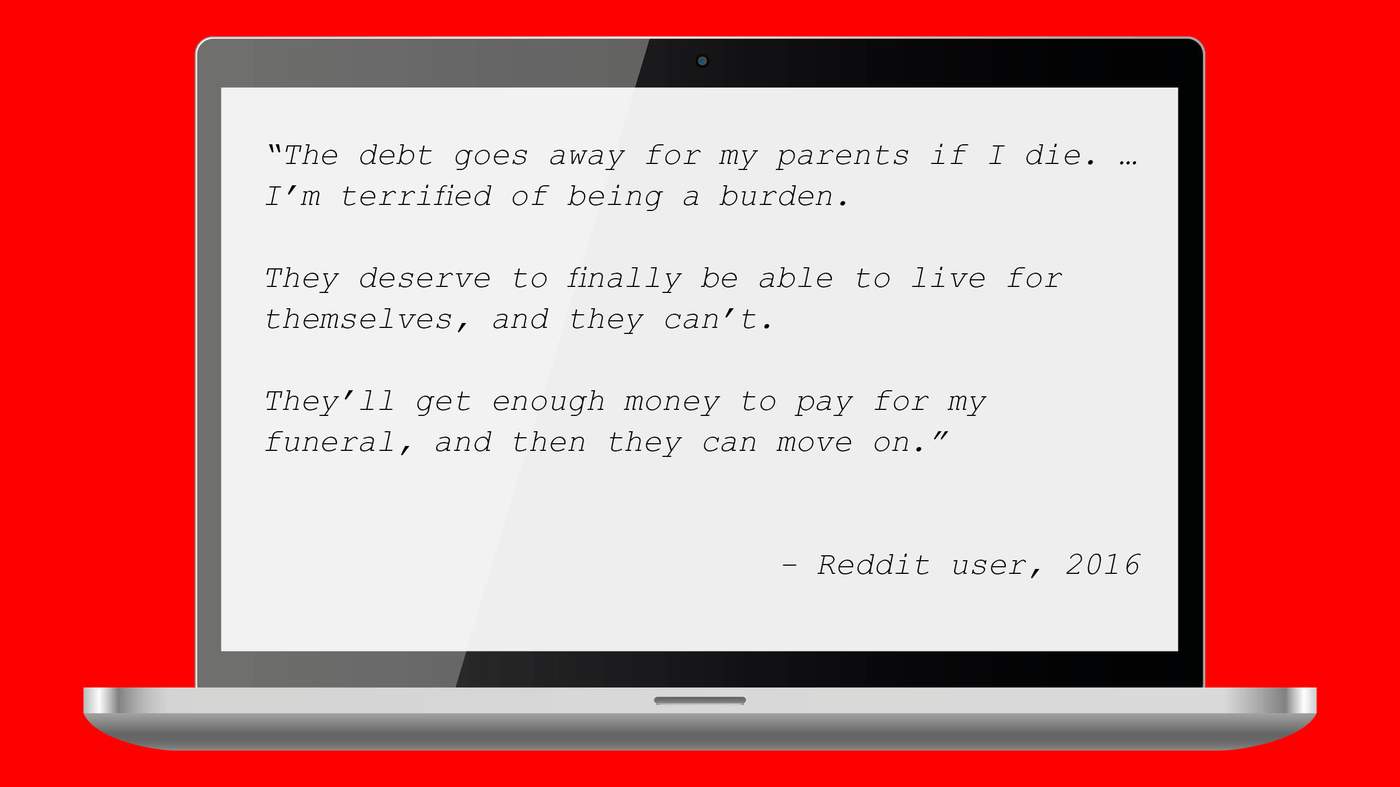

He can't ask his parents for help. He knows Bentley is already tied in to three different payment plans - one of which is for his bike - and he is scared of becoming a burden on them.

He starts to get more desperate.

Debt and depression

As well as his physical health, Jerome's mental health starts to suffer.

He starts looking for help online, and comes across people's personal experiences shared on forums like Reddit.

Debt is a topic that is often discussed online everywhere from Money Saving Expert to Mumsnet.

These sites, he finds, are full of posts from people in absolute despair.

Young people in unstable work like Jerome's are one-and-a-half times more likely to report having a mental health problem compared with those in more secure work.

Dr Alex Wood, a sociologist at Oxford University, has spent the last six years looking at the link between mental health issues and these kinds of jobs.

He's found that people in precarious working situations are left feeling more anxious, depressed, and financially insecure.

"Some workers have even told me that they'd be in tears, or would see their colleagues in tears," he tells BBC Three. "One minute you walk in and you know what you're doing; the next minute you walk in and you have no idea. It creates a really stressful atmosphere."

Alex adds that one zero-hours worker, who took part in his research, told him, "It's caused me so much stress and anxiety, it's sad and heartbreaking. I've had to hold back tears at work, and I've had to have a lot of therapy from working for this employer. I need stress management and anxiety management just from working here."

Another told him, "I've got two kids and a mortgage and I'm going to be out of a job because I can't do these hours."

"They put a lot of stress on people," another worker added. "I used to be in tears."

Jerome's asthma worsened in the cold weather, and he struggled to make deliveries. (Still from BBC Three factual drama Killed By My Debt.)

Dr Morag Henderson, from UCL, also tells BBC Three that she had found people in unstable work were at higher risk of mental ill health, as well as poor physical health.

"I speculate that debt might be one of the drivers of this," she says. "It might be as a result of lower income or debt, it might be about low status, or just that uncertainty that people have in their income and lack of job security causing some stress."

She says that 5% of people aged 25 in 2015 - the year that Jerome started working - were on zero-hours contracts, and that there's a disproportionate number of ethnic minorities in unstable work situations.

"Even when they have the same GCSEs, the same A-levels, the same education generally, people from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to end up in unstable work at the age of 25," she says. "So instabilities in the labour market are affecting people disproportionately."

Morag added that being on a zero-hours contract is associated with a 41% lower chance of reporting having good, very good or excellent health, compared to those not on those contracts.

The Newlyn bailiff visits Jerome's house for a second time after not receiving the agreed repayments.

This time, he clamps Jerome's bike.

When Jerome tries to stop him, he calls the police to report him for allegedly breaching the peace.

Jerome needs his bike to work, and has absolutely no hope of paying off his debts without it.

Bailiffs are not actually allowed to seize tools of trade that are valued at less than £1,350.

At this point, Newlyn has assessed Jerome's bike and valued it between £1,500 and £2,000 - although it will later be valued by Honda, the manufacturer, at just £400.

Martin Rogers, parking manager at Newlyn, later admits at the inquest that the company's system was only able to accurately value cars - not bikes.

Later the same day

Jerome leaves home.

The bailiff, who is still waiting outside his house, is the last person to see him alive.

On 8 March 2016, Jerome is found by his older brother Nat and their family friend Michael Strong.

His body is found in an area of the woodlands where he used to play as a child.

The inquest

More than a year later, in April 2017, a coroners' court in Croydon hears about Jerome's money problems in the run-up to his death, and about the bailiff's visits.

Nat tells the inquest: "I believe he [took his own life] because he wanted to have no more debt."

The family's GP adds that Jerome hadn't had a history of depression or other mental illness.

Jacqueline Devonish, the assistant coroner for south London, records a verdict of suicide.

"It's evident that he was stressed by being in debt," she says.