Every day, Amy Dunne had to walk past protesters shouting and jostling for position outside the High Court in Dublin.

She was then just 17 and known in the court case and the media simply as Miss D.

I remember people protesting over me, praying for me, all the time”

Her face had to be blurred in newspapers and on television, but there was still a constant click of camera shutters as she arrived.

“I remember people protesting over me, praying for me, all the time,” she recalls.

The placards outside read “Abortion is forever” and “She’s a child, not a choice”. There were blown-up pictures of a foetus in the womb.

It was 2007. Just a few months before the court case, Amy had been looking forward to finishing school and starting a career. She wanted to be an actor, or perhaps a chef.

Instead, the most intimate details of her life became a national topic of conversation. Miss D became - without choosing to - another milestone in Ireland’s long battle over whether it should allow abortion.

“I felt like I was committing a crime. I was being made to believe… that I was committing a crime.”

Repealing the Eighth Amendment - brought in in 1983 - will let the law be changed to allow for abortion in cases of fatal foetal abnormality and where the physical or mental health of the mother is in danger.

With the repeal of the amendment, a new law will bring in abortion - effectively “on demand” - up to the 12th week of a pregnancy.

That’s exactly what Kathy Sinnott wanted Ireland to avoid when she started campaigning in 1983. Then she was struggling to raise her children in trying times but she felt she had to follow her conscience.

“All three of mine were crisis pregnancies. I was always close to the wire on funds.”

Back then Michael Jackson’s Billie Jean was topping the charts in Ireland and the newspaper headlines were about the ailing economy and record levels of unemployment.

“I was kind of sometimes a single mom and sometimes not,” says Kathy, who had emigrated from the US.

Her husband had walked out on the family, occasionally returning for short periods.

She had three small children at the time. Her four-year-old son Jamie had severe disabilities, and still wasn’t walking.

But despite all of her responsibilities she decided to become involved in one of Ireland’s most divisive ethical struggles.

The UK (although not Northern Ireland) had legalised abortion in 1967. Six years later, the Roe v Wade ruling effectively created a right to abortion in the US.

But in Ireland it remained illegal. Anyone wanting to terminate a pregnancy had to cross the Irish Sea. In 1983, there were 3,677 who made that journey to seek an abortion in the UK. It wasn’t something people liked to talk about.

That changed. Despite the liberalisation going on elsewhere, Ireland held a referendum on whether to introduce a constitutional ban that would ensure that abortion stayed illegal.

Kathy supported the move because she thought “the life of every single person is sacred and precious from conception to natural death”.

Now a mother of nine, who has campaigned for disability rights and been an MEP, she’s still intensely proud of her campaigning 35 years ago.

Abortion was already illegal under the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act but after Roe v Wade some feared judges in Ireland might also be able to create a ruling that would allow abortion.

Above: Politician (and future taoiseach) Bertie Ahern passes an anti-abortion campaigner outside the Dail during the 1983 referendum campaign

A small group of activists, backed by the Catholic Church, worried about pro-choice campaigners fighting for a change in the law. To cut this off at the pass, they lobbied for a constitutional provision prohibiting it.

Kathy strapped Jamie in a pushchair and canvassed in her local area, north Cork, in the south-west of the country. She found lots of people receptive to her anti-abortion message.

“On the doors, it was not a hard sell.”

Ailbhe Smyth, now a prominent advocate for abortion and LGBT rights, had a very different experience campaigning for the other side of the argument.

The academic had returned from France to get involved. She believed the right to choose an abortion was “vital for women’s independence and autonomy”.

Back in 1983, she says she was spat at in the street outside the General Post Office in Dublin and called a “baby murderer”.

During TV and radio debates, discussions often descended into shouting matches.

“[There was a view that] we couldn’t have un-Catholic things happening, and particularly not carried out by women,” she says.

After independence from the UK, the Catholic Church, already culturally influential, played a powerful role in the newly formed Irish state.

In 1937, the Church was given a “special position” in the new constitution, which wouldn’t be removed until the 1970s.

But 50 years later there were some who felt the Catholic Church still had too much influence over Irish attitudes towards sex and reproductive rights.

The sale of contraceptives without prescription wasn’t to be made legal until 1985. Divorce was also still illegal. The last Magdalene laundries, Catholic-run institutions where unmarried pregnant women were sent to work in punitive conditions, were still in operation.

On 7 September 1983, 67% of voters backed the introduction of the Eighth Amendment of the Irish constitution.

It effectively banned abortion, even in cases of rape or incest, or where a foetal abnormality made the chances of a baby’s survival very slim.

The legal impact of the amendment was to make it “impossible for the Irish parliament to legalise abortion in anything other than last resort cases”, says Fiona de Londras, professor of global legal studies at the University of Birmingham, and a backer of the repeal of the amendment.

It also meant that the state could take pregnant women to court “to defend and vindicate” the right to life of the foetus if it was considered to be in danger, she says.

For Kathy, the result of the 1983 referendum was a welcome protection for the unborn in Ireland. “I’m glad I played a tiny role in saving lives.”

But Ailbhe also feels the same now as she did in 1983 - that the Eighth Amendment harmed women.

“And that I will not tolerate and I don’t think a democracy should tolerate it either.”

Over the course of the next decade the issue wouldn’t go away.

On 22 February 1992, wearing a dark overcoat and blue Lennon sunglasses, the singer Sinead O’Connor greeted crowds in central Dublin.

Clutching a few sheets of white paper, she began to read a short statement.

“The bad decision made by Judge Costello is an invasion of the civil rights of all Irish women.”

Just a few days before, a teenage girl - later known as Miss X - had been prevented from travelling to the UK for an abortion.

She was a 14-year-old from Dublin who had become pregnant after being raped by a friend of the family. She told her mother she was suicidal.

Her parents decided to travel with her to the UK for a termination.

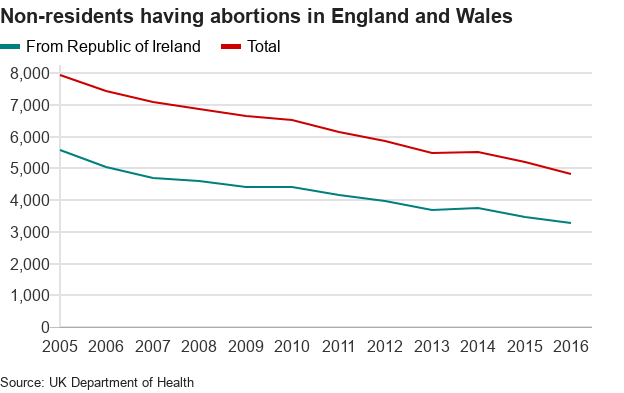

The number of Irish women travelling to the UK for a termination has fallen in the last decade

They reported the rape to their local police station and asked whether DNA taken from the foetus could be used as evidence.

Less than 24 hours later, a court order was put in place to stop the 14-year-old leaving the country. The judge ruled that the girl should be prevented from leaving Ireland for nine months.

Mass demonstrations began on Irish streets.

1992: A pro-choice rally in response to the Miss X case

At one pro-choice rally, the crowd was told that Ireland was an “internment camp” for pregnant young women.

An appeal was made to the Supreme Court and this time the court ruled that Miss X should be permitted to travel because of the suicide risk - a woman should have the right to access an abortion when her life was in danger.

In the end Miss X had a miscarriage in a hospital in England while waiting for a termination.

After the Supreme Court decision, the Irish government was left having to legislate to make changes.

Anti-abortion groups feared the judgement would be a slippery slope to much wider access to abortion. They demanded a referendum to roll back the ruling.

Anti-abortion campaigner Kathy Sinnott remembers praying for Miss X. She believes even in cases of rape abortions should not be allowed.

Pro-choice and anti-abortion activists again took to the streets.

Later that year, the Irish public voted not to overturn the ruling. They also voted in favour of freedom to travel abroad for an abortion and freedom of information on abortion services.

Despite the result, successive governments did not make any attempts to change the law.

“It was easier just to do nothing, and to let case after case take place and deal with that through the courts. It wasn’t going to be a vote-winner,” says Dr Lisa Smyth, author of Abortion and Nation: The Politics of Reproduction in Contemporary Ireland.

Fifteen years later Amy Dunne’s case arrived in the High Court.

Amy remembers the baby hamper she was given on the morning of her 17th birthday. She was looking forward to finding out the sex of her baby at the routine scan due that afternoon.

It wasn’t an ideal time to be pregnant. She had been placed in state care after a dispute with her mother.

But despite her initial shock at being pregnant, she began to feel excited.

At the hospital, a flicker of confusion ran across the nurse’s face.

Amy's baby girl had anencephaly - a rare condition that prevents part of the brain and skull from developing.

Doctors said the child would not survive more than a few hours after birth.

Distraught, she desperately tried to come to terms with the news.

“You know there are people out there who have miracles. This wasn’t going to be a miracle… It was my body, I couldn’t run from it.”

Amy subsequently told her social workers she wanted to go to the UK for a termination.

As a teenager in the care of the Irish state, she says her social worker told her she was legally forbidden to do so. The social worker said that they had written to the police to prevent her from travelling.

Before she even had a chance to think, Amy ended up in court, surrounded by “loads of people in wigs and black gowns” and unable to understand a word of what was going on. Protests continued outside.

“People hadn’t a clue about the condition that my child had - it was black and white to them.

“There was no respect for my life, there was no respect for my mental health.”

Her story was front page news every day, but Amy was never called on to speak. She felt ill in court as she waited for a decision.

On the day of the ruling Amy was too unwell to attend. She waited anxiously at home for her solicitor to call.

The court ruled that nothing could prevent Amy from seeking a termination in the UK despite being in state care.

The judge said the case was about the right to travel, not the right to an abortion, and sharply criticised the Irish authorities for their handling of the situation.

At the time, the government agency in charge of her care said it acted in accordance with what it believed to be “the correct course of action”, and that it always believed a court order was necessary for Amy to travel to the UK.

After Amy’s victory in court she found herself questioning her decision and spending hours researching abortion procedures online.

“I was emotionally, mentally, on my own.”

An anonymous donor promised her family 100,000 euros if she decided not to go through with it. Her mother rejected the offer. Despite the difficulties they were having, she accompanied Amy to the UK.

On the journey from Dublin to Liverpool, Amy was terrified someone would recognise her as she boarded the plane.

“I was paranoid, so paranoid in the airport.”

2007: Pro-choice campaigners outside the Irish high court

Women in Amy’s situation who terminate their pregnancies typically have the option of a surgical abortion or medical induction, where they go through labour and delivery.

Amy chose the latter.

“I touched her, I have pictures with her fingers, her whole hand touching my finger.”

I am haunted by my story, by similar stories”

Return flights had been booked for the day after the procedure, so she had little time to spend with the body of her baby girl, who she called Jasmine.

Amy wanted her daughter’s remains to be taken back to Ireland so she could be buried near her home in Drogheda.

When she arrived home she started to feel angry at how Ireland’s laws affected women in her situation who travel abroad. Her experience, she says, has “ruined” a part of her.

“I am haunted by my story, by similar stories.

“That was the most petrifying, degrading and disgusting thing I will ever have to do in my whole entire life.”

She struggled to cope with the grief of losing her baby daughter, and for years afterwards, she would find herself visiting the grave in the middle of the night.

Savita Halappanavar loved her life in Galway, loved the pace of life on the west coast of Ireland, loved the thriving arts scene.

She organised dance classes for the tight-knit Indian community there, as well as parties and social events.

Savita Halappanavar

Her husband Praveen worked in a medical device company and Savita, a trained dentist, was taking exams so her qualifications would be recognised in Ireland.

“No-one lived like her, the way she did. She had so many dreams,” says Mrudula Vasepalli, Savita’s best friend in Ireland.

She remembers her friend's excitement on finding out she was pregnant. Mrudula was the first person Savita told.

Praveen and Savita were going to call their baby Prasa - a combination of the first syllables of their names.

Praveen Halappanavar, pictured outside the inquest into his wife's death

When Savita started getting cramps on a Sunday evening in October 2012, at 17 weeks pregnant, she went to the local hospital.

Later that night, her waters broke and she was told her baby would not survive.

One week later, Savita was dead.

Doctors had told her a miscarriage was inevitable. The risk of infection was high because her waters had broken. She was put on antibiotics as a precaution.

Knowing her pregnancy could not continue, Savita requested a termination.

But, as a foetal heartbeat was still present, her consultant told her it was not possible to terminate the pregnancy.

The midwife manager tried to explain the situation to Savita. She said it couldn’t be done by the hospital because Ireland was a “Catholic country”.

Mrudula watched as her friend’s condition deteriorated in hospital. Savita developed a fever and was given stronger antibiotics.

“It’s not pro-life or pro-choice or anything like that. It’s a medical procedure - she should have got it,” says Mrudula.

By the third day after arriving in hospital, Savita was no better. This time, even though a foetal heartbeat was still present, the consultant now said a termination could happen.

Before the procedure was carried out, Savita gave birth to a dead baby girl.

Her health continued to worsen. She began to suffer from septic shock, and her organs started to fail. She died at 01:09 on 28 October 2012.

Mrudula dressed her body for the undertakers. It was the last thing she could do for her friend.

On the day Savita and her husband would have been celebrating their fifth wedding anniversary, the jury in the inquest into her death returned a verdict of medical misadventure.

Three independent reports identified failings in the medical care Savita received.

One recommended that medical professionals and the parliament “consider the law including any necessary constitutional change”.

In a statement, the hospital’s clinical director apologised to her husband “for the events related to his wife’s care that contributed to her tragic death”.

Savita’s case had a dramatic effect on the debate in Ireland.

"Within a week things had changed. And it’s never been the same since,” says Dette McLoughlin, a pro-choice campaigner from Galway whose group were contacted by Savita’s friends.

They in turn called the Irish Times, who, on 13 November, put the story on the front page.

Protests were held in Dublin, Limerick, Cork, Galway, and Belfast, but also in London and Delhi, calling on the country to look again at its abortion laws.

“Everybody just thought that could have been me or that could have been my partner, my daughter,” says Dette.

"Her picture made her real.”

All of this, says Dette, coincided with a generation of young women for whom abortion was less of a taboo subject.

For the first time, she says, people began to reflect on what Ireland’s abortion laws might mean for ordinary maternity care.

But anti-abortion groups denied that the law was to blame. Cora Sherlock, of the Pro-Life Campaign says the case is “still being misrepresented by some on the pro-repeal side”.

“The Eighth Amendment did not cause or bring about her death.”

She says pregnant women in Ireland receive the care they need if they become ill, even if that unintentionally results in the death of an unborn baby.

But pro-choice groups continued to ramp up political pressure and push for a full repeal of the Eighth Amendment.

Anna Cosgrave, a student from Dublin at the time, was so moved by the Savita case that she designed black T-shirts emblazoned with a simple white slogan - “Repeal”.

They quickly spread around festivals, concerts and protests across the country.

More and more women who had undergone an abortion began to speak publicly about their experiences. Some spoke out about breaking the law by ordering abortion pills online.

In January 2018, more than five years after the death of Savita Halappanavar, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar called a referendum.

Savita’s case had a dramatic effect on the debate in Ireland.

"Within a week things had changed. And it’s never been the same since,” says Dette McLoughlin, a pro-choice campaigner from Galway whose group were contacted by Savita’s friends.

They in turn called the Irish Times, who, on 13 November, put the story on the front page.

Protests were held in Dublin, Limerick, Cork, Galway, and Belfast, but also in London and Delhi, calling on the country to look again at its abortion laws.

“Everybody just thought that could have been me or that could have been my partner, my daughter,” says Dette.

"Her picture made her real.”

All of this, says Dette, coincided with a generation of young women for whom abortion was less of a taboo subject.

For the first time, she says, people began to reflect on what Ireland’s abortion laws might mean for ordinary maternity care.

But anti-abortion groups denied that the law was to blame. Cora Sherlock, of the Pro-Life Campaign says the case is “still being misrepresented by some on the pro-repeal side”.

“The Eighth Amendment did not cause or bring about her death.”

She says pregnant women in Ireland receive the care they need if they become ill, even if that unintentionally results in the death of an unborn baby.

But pro-choice groups continued to ramp up political pressure and push for a full repeal of the Eighth Amendment.

Anna Cosgrave, a student from Dublin at the time, was so moved by the Savita case that she designed black T-shirts emblazoned with a simple white slogan - “Repeal”.

They quickly spread around festivals, concerts and protests across the country.

More and more women who had undergone an abortion began to speak publicly about their experiences. Some spoke out about breaking the law by ordering abortion pills online.

In January 2018, more than five years after the death of Savita Halappanavar, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar called a referendum.

Her position is heard often in Ireland but perhaps one that has not been well-reflected in the debate - people who would accept abortion in “hard cases” but are opposed to the kind of easily available abortion that applies in many Western nations.

Families and friends across the country had difficult conversations about the vote, and the referendum divided the cabinet.Though he campaigned for a yes vote, Ireland’s Deputy Prime Minister, Simon Coveney, initially felt uncomfortable about unrestricted access to abortion up to 12 weeks.

Many commentators believed there was a clear majority in support of allowing abortion in cases of rape or incest, or where a woman’s life is at risk, and in cases of fatal foetal abnormality.

But with the changes likely to go further than that, it was hard to predict how the vote would go.

Many of the arguments that were had on doorsteps were the same as 1983, but some think one element of the debate had changed.

Cora Sherlock of the Pro-Life Campaign consistently says abortion is a “human rights” issue, not a religious one.

The Archbishop of Dublin, Diarmaid Martin, said the church “must be pro-life when it comes to the unborn”. But the Association of Catholic Priests also called for an end to the pulpit being used by campaigners to promote their views.

On the pro-choice side, Ailbhe Smyth agrees religion doesn’t have the same influence any longer. Now people are led by “their own conscience”, she says.

Others, like 25-year-old Siobhan, not her real name, still point to the Church’s legacy. Because of their faith, she hasn’t told her parents that she had an abortion.

“I had quite a Catholic upbringing, I went to mass every Sunday. My parents would support me in a lot of things but abortion was one of the things they said they outrightly believe is murder.”

Venetia says she lives in a “liberal” country now, where people view the referendum “in a secular light”. She campaigned in favour of same-sex marriage in the referendum held in 2015, when Ireland became the first country in the world to legalise this by popular vote.

But this abortion referendum was a very different situation.

“We are now taking away rights of all unborn children and that’s a regressive step.”

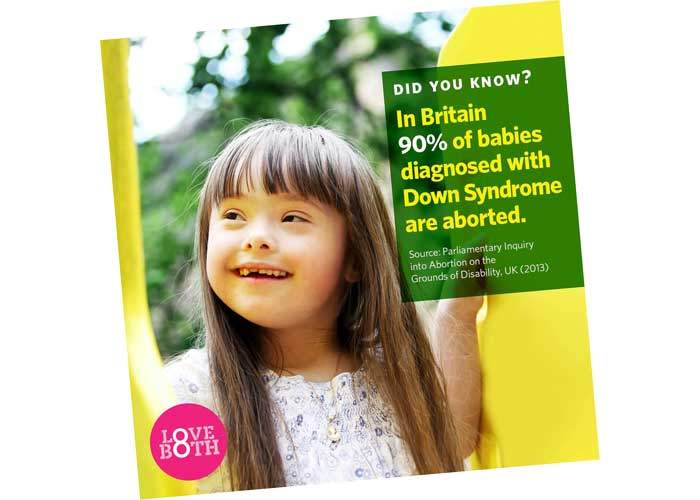

One of the most striking images in the 2018 referendum campaign did not show graphic images of abortion. Instead it featured a beaming, gap-toothed child with long, dark hair.

The little girl had Down’s syndrome, a genetic condition that causes learning difficulties.

The image was published by the anti-abortion Love Both campaign with the slogan: “In Britain 90% of babies diagnosed with Down Syndrome are aborted.”

A “No” campaign poster showing a child with Down's syndrome

Statistics on abortion rates for Down’s syndrome are complex.

A report on the number of Down’s syndrome children born in England and Wales in 2013 estimated the proportion of women having a termination after a prenatal diagnosis was 90%.

But some women choose not to have the test for Down’s syndrome and go on to have babies with the condition. So it’s not the case that 90% of all pregnancies with Down’s are terminated.

Sinead McBreen, from County Cavan, is mother to three-and-a-half year-old Grace, who has Down’s syndrome.

She and her daughter have featured in the Love Both campaign.

In the family home, Grace plays with her siblings. All four have learned sign language to communicate with her, because Down’s syndrome children usually start speaking later than others.

It’s hard, Sinead says, and not what anybody would choose, but “she’s amazing”.

Having a sibling like Grace, Sinead says, has had a positive impact on her other children, who see that there’s “more to life” than make-up and computer games.

“It’s a lovely thing that they see the world isn’t perfect.”

Still, the referendum made Sinead feel uneasy.

“In certain ways, Ireland has always been unique in that it’s protected the unborn.”

Sinead trained as a nurse. But it wasn’t until she was pregnant with Grace that she was forced to confront her own views about abortion.

Up until that point, she had always considered herself pro-choice.

When Sinead’s prenatal scans showed significant abnormalities, she says the medical team told her that her pregnancy would most likely not survive. They advised her to consider all of her options, including a termination in the UK.

Further tests were carried out. She was told it was very likely that her child had Down’s syndrome.

The news was upsetting and hard to digest. But it also gave Sinead hope her baby would live.

All I heard were the negatives. All I wanted to do was give her a chance."

The doctors were still convinced that the baby would not survive beyond 20 weeks.

“All I heard were the negatives. All I wanted to do was give her a chance."

Sinead’s pregnancy progressed normally and Grace was born in November 2014.

Ireland’s laws on abortion, she says, gave her time to think. “I know the Eighth Amendment is the reason my daughter is with me today.

“I looked at the scans on the screen and I could see this person. I felt she had rights.”

A few months after Grace was born, Sinead attended her first anti-abortion rally.

She’s left with worries over what legalising abortion might mean for children like Grace.

Ireland’s proposed new law would not allow a diagnosis of likely disability as a reason for an abortion after 12 weeks.

And currently, it is rare to receive a Down’s syndrome diagnosis within 12 weeks - the time limit for unrestricted access for abortion that the government is proposing.

But people like Sinead worry that improved testing will come and the vast majority of babies with Down’s would be aborted. She had a telling encounter while on holiday.

When Sinead’s family visited Copenhagen on a short weekend break, she was struck by a stranger’s comment about Grace: “You don’t see it here anymore.”

In 2006, Denmark was the first European country to introduce free first trimester screening for Down's syndrome and the majority of women there choose to receive it.

After that, the number of infants born with Down’s syndrome decreased by about 50%, says Dr Ann Tabor, professor of foetal medicine in Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

In 2016, says Tabor, 135 cases of Down’s syndrome were detected through pre-natal screening. Of these, only four children were born.

Down Syndrome Ireland described the Love Both literature as “disrespectful”, and called on campaigners to “stop exploiting children and adults with Down syndrome to promote their campaign views”.

The Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, passes a Vote-No poster

The Health Minister, Simon Harris, also condemned posters featuring Down’s syndrome children. He said it was “very upsetting to say to people with Down syndrome in Ireland that you've only been born in Ireland because of the Eighth Amendment”.

Prof Fergal Malone, Master of the Rotunda Maternity hospital in Dublin, dismisses claims that women would always choose to terminate Down’s syndrome pregnancies.

Currently, he says, there is no form of free screening for the condition in Ireland’s national health service, and only half of maternity hospitals provide a basic 20-week scan.

Some choose to pay for more sophisticated screening. Of those who were given a prenatal diagnosis of Down’s syndrome in the Rotunda hospital, about 56% of women decided to terminate their pregnancies by travelling to the UK.

“It’s hard to know what might happen in Ireland, but certainly our figures so far don’t suggest 95%, or 100% termination rates, far from it.”

But for Sinead, nothing will dispel her doubts.

“You look to the future and you think where does this end. I don’t want to go down a road where we live in a world like that.”

It’s more than a decade since Amy Dunne went to court to be allowed to travel for an abortion.

As well as the grief, Amy also had to deal with the fallout from the case. Her sex life and marital status were discussed on online forums. Though most people in Ireland didn’t know her name, everybody in her home town knew what had happened.

Amy’s now a trained beauty therapist and a mother to a 10-year-old son. She couldn't wait for the referendum campaign to be over.

“It’s all too much, my head feels like it will explode.” She felt like she was being put on trial all over again.

The Yes side urged the public to vote for “compassion”, “care” and “change”. Celebrities call for “a just society, for a fairer Ireland”.

The No side called on Irish people to “save lives” and protect against a “licence to kill”. Softer slogans urged them to be “pro-woman, pro-baby, pro-life”.

Now the repeal side have won. Abortion will soon be allowed in Ireland.

Addressing teary-eyed crowds in Dublin, the Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar said “a quiet revolution” had taken place.

Leo Varadkar speaking in Dublin after the referendum result

Anti-abortion campaigners said 25 May was “a sad day for Ireland”.

But the result is unlikely to put an end to the country’s 35-year abortion struggle - both sides will fight on.

Pro-choice activists have already shifted the focus on to Northern Ireland where abortion remains illegal. Anti-abortion campaigners will want to oppose a move to further easing of restrictions in the republic.

The battle lines have been redrawn in a country that has radically and rapidly changed.