A tale of two pontiffs

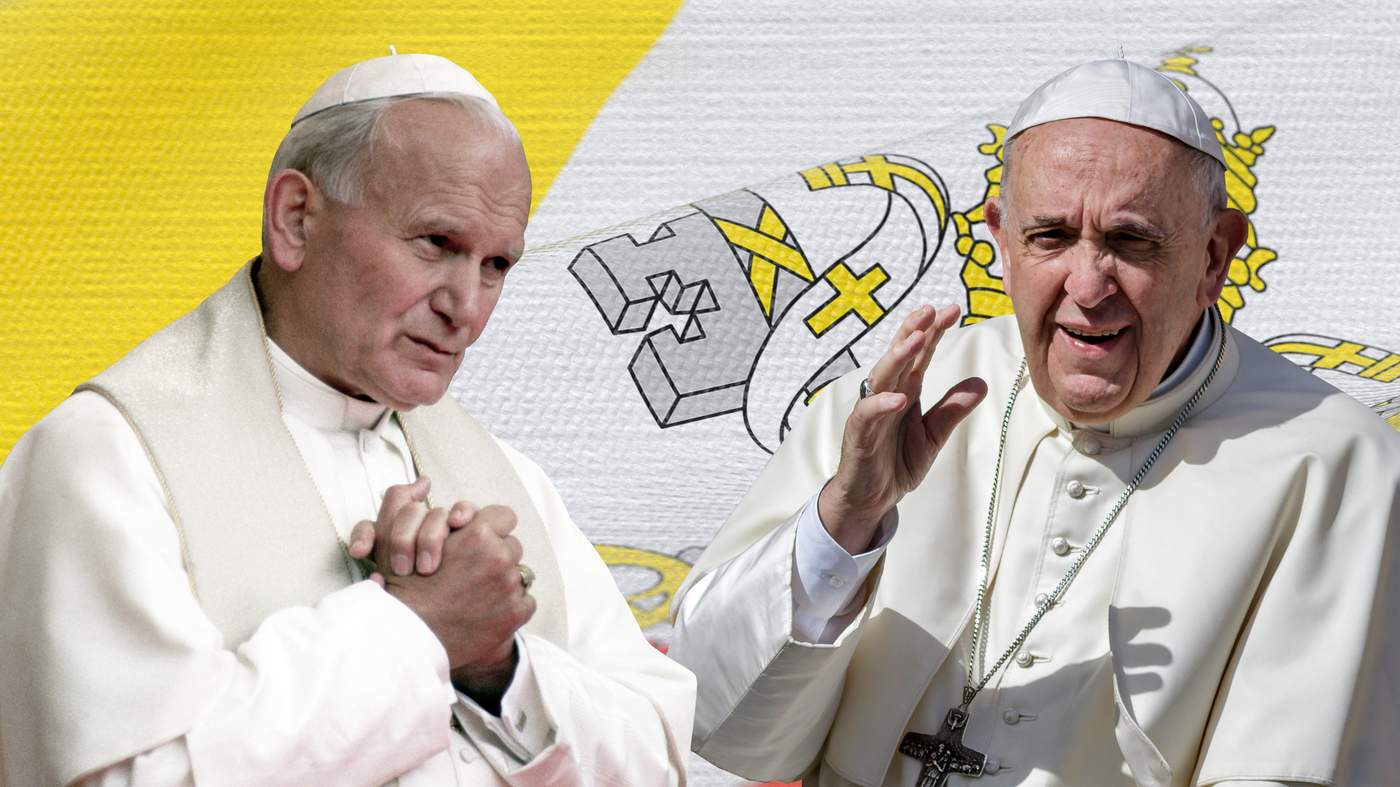

It is nearly 40 years since Pope Saint John Paul II's aeroplane swooped on to the runway at Dublin Airport.

Roman Catholic Ireland held its breath as the Polish Pope knelt to kiss the tarmac, cape whipped by the wind.

People called it a once-in-a-lifetime event.

In Galway, thousands cheered as Pope John Paul II was welcomed on to a stage by the Right Reverend Eamonn Casey to celebrate a youth Mass.

Few people knew at the time that Bishop Casey had a five-year-old son.

When the news finally broke in 1992, the idea of an Irish Catholic bishop having sex, never mind fathering a child, was shocking to many believers.

But that scandal paled in comparison with the deep fault lines within the Church that were to be exposed.

The Catholic Church has been rocked by revelations of paedophile priests, sexual abuse in Catholic-run orphanages, and the exploitation of women in mother-and-baby homes.

The Ireland that Pope Francis will visit is a very different country to that which greeted his Polish predecessor.

Ireland has seen seismic changes in public attitudes to social issues including abortion, contraception, divorce and same-sex marriage.

Pope Francis has won hearts the world over for his humility.

He speaks out against economic injustice, conflict, the death penalty and the destruction of our environment.

When elected in 2013, Jorge Mario Bergoglio chose his papal name to honour St Francis of Assisi, because of the saint’s devotion to the poor.

The charismatic Argentine can expect a warm welcome in the Republic of Ireland - but not the same breathtaking devotion inspired by Pope John Paul II - who was declared a saint by Pope Francis in 2014.

Father Brendan Hoban has recently retired - he’s 70; it was time.

The Republic of Ireland is a country of ageing clerics - 70 is now the average age of its priests.

With few young men to step into older men’s shoes, this papal visit comes at a time when almost every Irish diocese is facing a vocations “crisis”.

Fr Hoban is a founding member of the Association of Catholic Priests.

He stepped down as parish priest of Moygownagh, County Mayo, at the end of July, and his situation illustrates why so many parishes are struggling.

"There's nobody to replace me," he laments.

A parish council has taken over the day-to-day running of Moygownagh and a neighbouring priest is coming in to celebrate Mass and the sacraments.

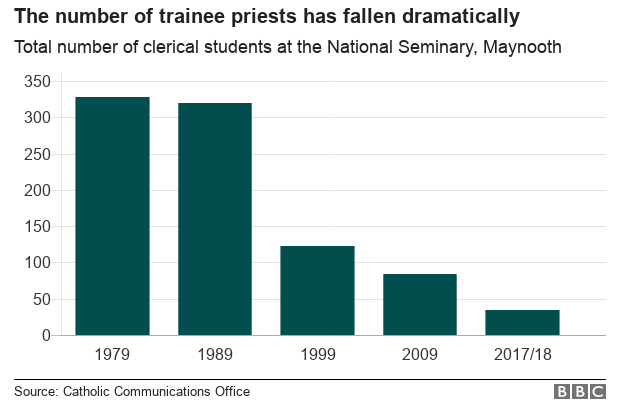

The picture was very different when, as a teenager, he entered Ireland’s national seminary - St Patrick's College, Maynooth, County Kildare - in 1966.

"There were 84 students in my class and about 50 of those were ordained," Fr Hoban recalls.

"The class ahead of me had about 110.”

Last year, six men enrolled at Maynooth seminary, the lowest in its 223-year history, according to the Irish Times.

Founded in 1795 and designed to house 500 trainees, Maynooth was once the largest seminary in the world.

It currently houses 35 seminarians - a handful of men preparing to cater for a country of more than 3.7 million Catholics.

Maynooth used to be supported by a network of smaller diocesan seminaries across the Republic of Ireland, but they shut one by one.

Northern Ireland’s only Catholic seminary - St Malachy's in Belfast - is to close later this year.

"If you have no priest, then you have no Mass, and if you've no Mass, then you have no Church," Fr Hoban warns.

The Church must embrace change to survive, he says.

The priesthood should be opened to women and married Catholics, he argues, ending the centuries-old rule that only single, celibate men can be ordained.

In 1979, there were more than 6,200 priests throughout the island of Ireland. That figure has fallen to just over 3,900 but their age is the bigger problem.

"I'm just over 70 and I'm still the average age of priests in Ireland, which is absolutely bizarre," says Fr Hoban.

An increasing burden is falling on the shoulders of the country's elderly clerics.

Several are working beyond the age of 70, and many retired clerics are regularly called upon to help out.

Five years ago, Fr Hoban wrote a book on Ireland's "disappearing priests" which warned that the country was facing a "Eucharistic famine".

Now, he says his predictions are “coming true”. He criticises the Irish Bishops' Conference for failing to take decisive action.

"We need immediately to ordain married deacons," Fr Hoban says. "We need immediately to decouple celibacy from the priesthood; we need immediately to invite back priests who have left to get married."

He argues there are enough men who gave up their vocation to start a family who could now "come back to tide us over the crisis”.

Fr Hoban also believes that the ordination of women is almost inevitable and suggests such a move may be "only down the road".

He has previously accused the institution of thinking it had a "God-given right to patronise, condescend, disrespect, ignore, and presume that women today will accept the excruciatingly embarrassing efforts we make, as a Church, to limit their role".

The Association of Catholic Priests represents more than a quarter of all the priests in Ireland.

This summer, it carried out a survey ahead of Pope Francis’s visit, asking almost 1,400 people what they wanted to say to the pontiff about the Church in Ireland.

The ACP said the results revealed “huge support for a radical reform” of the priesthood, with the number one proposal being “an equal role for women in the Church”.

The status of Catholic women is a "neuralgic issue" for the Church, says Fr Hoban.

If the Church doesn't sort that very soon, we're going to lose an awful lot of our people. We've lost their minds already, but we're going to lose their bodies in the Church, in a sense.

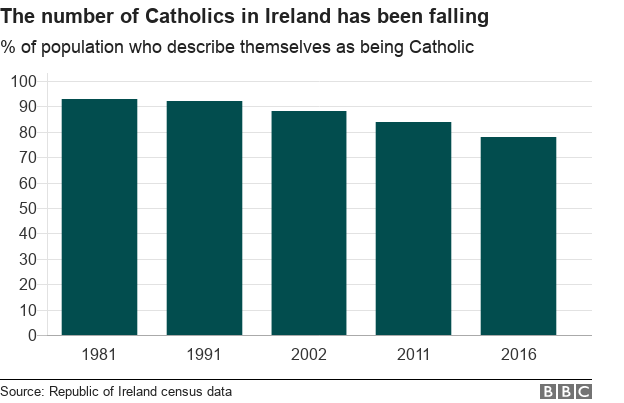

Ireland remains a “predominantly Catholic country”, according to the Irish Central Statistics Office (CSO), but the percentage of the population who identify as Catholic has fallen.

A census carried out in 1981, just two years after the last papal visit, showed that Catholics made up 93% of the population.

By 2011, that figure had dropped to 84%.

And the most recent census, in 2016, showed a further decline - to 78%.

The CSO said the 2011-2016 drop was accompanied by a corresponding rise in the number with no religion, who now account for nearly 10% of the Irish population.

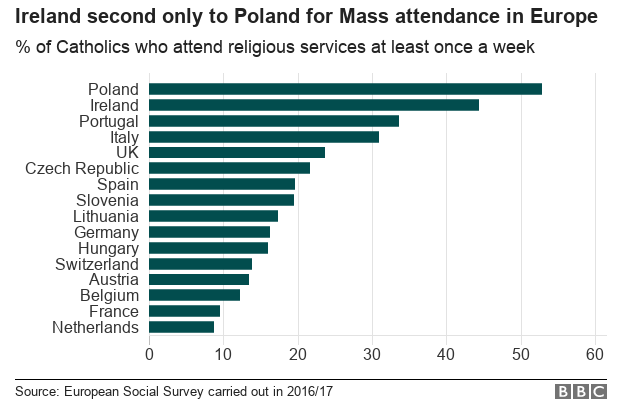

Describing yourself as Catholic on a census form does not necessarily mean you actively practise your faith, but religious service attendance levels in Ireland are still relatively high, compared with other European countries.

Of the 1,770 Irish Catholics who took part in the latest European Social Survey (ESS), 44% said they attended religious services at least once a week, second only to Poland.

Almost two-thirds (62%) of Irish Catholics said they attend services at least once a month.

Just under a quarter (24%) of young Irish Catholics, aged between 16 and 29, claim to go to Mass every week, according to analysis of ESS data from 2014 and 2016.

Only their peers in Poland and Portugal professed to be more devout.

The Archbishop of Dublin, the Most Reverend Diarmuid Martin, has warned about the “growing alienation" of young people from the Church - acknowledging the crisis is larger than the lack of vocations.

Fr Hoban says the Irish bishops have a moral responsibility to ensure there are enough priests to minister to future populations and to look after ageing clergy.

After 45 years of ministry - does he ever regret his vocation and would he make the same decision now?

"I certainly would look at it differently," he says.

I've had a good life as a priest and I've got a lot of satisfaction and happiness out of it, but... if I was a married priest, I think I would have been a better priest.

Mark Vincent Healy is one of the thousands of people in Ireland living with painful memories of child abuse.

From the age of nine until he was 12, he was sexually abused by two priests from the Spiritans order.

Picture: Mark Vincent Healy

It happened more than 40 years ago when he was at St Mary's College, Rathmines.

Mr Healy says it inflicted a "lifelong injury".

"There is a dark world, that has not been portrayed for people to understand, what it is like to live with post-traumatic stress disorder, caused in your childhood over issues of such violation and degradation as sexual abuse."

Mr Healy campaigns on behalf of other victims and took his fight for redress to the top of the Catholic Church.

Four years ago, he was the first male survivor of Irish clerical sex abuse to meet Pope Francis.

It was a "significant moment in history” for him but he says the institution must realise it is only at the beginning of its journey of restitution.

In the past 25 years, the Catholic Church in Ireland has been rocked by a catalogue of child-abuse scandals.

Smyth was at the centre of one of the first paedophile priest scandals

One of the most infamous was the case of Belfast-born paedophile priest Brendan Smyth, whose mishandled extradition led to the downfall of the Irish government in 1994.

Since then, the physical, emotional and sexual abuse of children by priests and members of religious orders across Ireland has been laid bare.

The 2009 Ryan Report collated evidence from 1,090 men and women who alleged they were abused as children in institutions in the Irish Republic, most of which were Catholic-run.

About half of them said they had been sexually abused.

The inquiry team concluded that "sexual abuse was endemic in boys' institutions" but that it was "impossible to determine" the full extent of the problem.

Although the Church did not sanction child abuse, its hierarchy was condemned for trying to cover up scandals, thus placing even more children at risk.

Priests and members of religious orders accused of abuse were often transferred to a different school or diocese or even sent to another continent.

The practice enabled some offenders to groom new victims unaware of their past, and it also allowed some to evade justice completely as they were moved outside the jurisdiction.

Picture: Mark Vincent Healy

Mr Healy says the full international ramifications of shuffling suspects in and out of Ireland is still unknown and it is an issue he hopes will be addressed during the Pope's visit.

The campaigner has personally experienced both success and failure in his attempts to hold suspects to account.

One of the priests he accused, Henry Moloney, received multiple criminal convictions for abusing Mr Healy and other schoolboys, one of whom later took his own life.

The second priest, Arthur Carragher, was transferred to ministry in Canada and could not be extradited to Ireland.

Before his death in Canada in 2011, Carragher admitted abusing two other Irish boys who took a civil action against him.

Mr Healy wants to know how many paedophile priests were sent abroad where they continued to abuse.

In 2006, the Church set up its own abuse watchdog - the National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church in Ireland (NBSCCCI).

Between 2011 and 2017, it published a series of reports outlining the history and known extent of child abuse in every diocese on the island, including separate reviews into religious orders who ran schools and residential institutions.

The data revealed that in one order alone - the Christian Brothers - 870 allegations were made against 325 brothers, 12 of whom were convicted.

But the island-wide audit did not tell the full story.

In its latest annual report, the watchdog noted a "significant increase" in the number of new claims and concerns about child abuse.

It recorded 135 new allegations in 2017-2018, most of them historical, compared with a total of 86 the previous year.

The board's spokesman said when a clerical abuse story gets significant national media coverage, it often prompts more victims to come forward.

Earlier this year, several victims of the late paedophile priest Malachy Finegan broke decades of silence to say he had sexually abused them at a school in Newry, County Down, and in the nearby parish of Clonduff, Hilltown.

More than 30 people say they were abused by Malachy Finegan

The Police Service of Northern Ireland has since set up a dedicated team to investigate Finegan's crimes.

More than 30 people have come forward to say they were abused.

Almost a quarter of a century after the Brendan Smyth case, the Church still has sins to confess.

Mr Healy has carried out his own research into abuse statistics, using data from the NBSCCCI’s all-island reports, and he highlights the low conviction rate in cases involving foreign missionaries.

"There were 2,086 accusations in the national audit against 811 missionary priests, of whom 43 were held to account," he says.

He laments the fact that of these cases, almost 95% did not result in a conviction.

In 1996, the Church began to set up dedicated helplines and cross-border counselling services for victims who suffered at the hands of priests and members of Catholic orders.

Over the last two decades, Towards Healing and its predecessor, Faoiseamh Counselling Service, have supported 5,470 people and provided 365,820 counselling sessions.

Mr Healy welcomes the efforts made, but argues that much more must be done for those who were robbed of their childhood.

I want to see far better, lifelong support for those who are abused, because their trauma doesn't end.

“This is an injury, sadly, which lasts a lifetime."

In the 40 years since Pope John Paul II visited Ireland, one of the country’s most noticeable changes has been in its attitude to sexuality.

Today, in a country where the prime minister is an openly gay man, a high-profile figure declaring their homosexuality would not merit much controversy.

Joni Crone featured on RTÉ's Late Late Show

But for Joni Crone, the stomach-churning moment in 1980 when she came out as lesbian on Irish television is etched in her memory.

Somebody offered her a vodka to calm her nerves.

This was an Ireland where people could be treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) to "cure" them of homosexuality.

A night out for anyone who was gay or lesbian could end in a beating.

Homosexuality was a crime.

Ms Crone's decision to speak out was prompted by the despairing women who rang the lesbian helpline.

She knew that coming out to a million viewers on the Late Late Show was risky.

She had friends lined up to whisk her out of the country, if things turned nasty.

The Late Late Show was hosted by Gay Byrne

She knew the eyes of Ireland were on her.

Byrne pulled no punches.

"What would compel a girl like you to appear on a programme like this and blow, as it were, her cover?" he asked.

She thought she was coming on to promote the lesbian helpline, but he stuck with personal questions.

He asked if her parents saw her as "somehow mentally deficient, sinful or culpably ignorant?"

"We often have the impression that people like you go about like ravenous wolves seeking whom you may devour," he told her.

"We're not all so promiscuous or so highly sexed as people imagine," she countered.

The following Monday, in work, the youngest man in the office came to shake her hand.

The managing director praised her courage.

But a trader on Camden Street, Dublin, spat at her and said she would not serve the “likes of her”.

Two years later, in 1982, 31-year-old Declan Flynn was kicked and beaten to death with sticks in Fairview Park, Dublin, by a gang of "queer-bashing teenagers".

The youths pleaded guilty to manslaughter and were sentenced to between one and five years - the sentences were suspended.

Mr Justice Sean Gannon, the presiding judge, said: "It's important the public should know it could never have been murder, although it was an appalling thing for Declan Flynn and his family."

He allowed the five accused to walk free because, he said, there was "no element of correction required" as they had "come from good homes and have experienced care and affection".

His ruling caused public outrage and led to one of the first big gay rights demonstrations in Dublin.

The switch in attitudes came slowly, says Ms Crone.

"We had the Irish trade unions and we had the women's council. We kept talking in small ways to maybe 20 people at a time. It was like a pebble in a pond."

The ripples spread, gathered force, swelled to a tidal wave.

It would be 1993 before consensual homosexual acts between adults were decriminalised in Ireland.

In May 2015, the Republic of Ireland became the first in the world to legalise same-sex civil marriage by popular vote.

Last year, Leo Varadkar was appointed Taoiseach - Irish prime minister. He is the son of an immigrant and openly gay - a symbol of a new Ireland.

Earlier this year, the Irish voted by 66.4% to 33.6% to overturn the country's ban on abortion.

"In 1979 when Pope John Paul II came to Ireland, there was so much reverence for him. Dublin was like a ghost town. Everybody was there," says Ms Crone.

With Pope Francis, it feels like he's coming to bolster the old guard. It's no surprise after the two referendums that he's here.

Now gay and lesbian people are integrated into Irish culture.

At this year's Pride celebrations, bus driver fathers picked up their gay sons and drove them joyfully in a rainbow bus through the streets of Dublin.

Within the Church, change is in the air.

At this week’s World Meeting of Families (WMOF) in Dublin, US priest Father James Martin will speak on “Showing Welcome and Respect in our Parishes for LGBT People and their Families”.

The Jesuit scholar is known for his liberal views on homosexuality and Pope Francis has appointed him to the Vatican's Secretariat for Communication.

Thousands signed a petition protesting against Fr Martin’s inclusion at the Dublin event, but it will go ahead.

Meanwhile, for Joni Crone, it is the country’s young who inspire her.

"Young people in their 20s have fire in their bellies," she says.

"They are just not going to take it anymore. I think that's brilliant."

One of the most chilling effects on people’s attitude to the Irish Church has come after revelations about its treatment of unmarried mothers and their babies.

In Tuam, Galway, in the 1950s and 60s, the clatter of hobnail boots on the road was the signal the "home babies" were passing.

They were poor, their hair clipped short.

They lived in the mother-and-baby home run by the Catholic Bon Secours sisters.

Their badge of shame was that they had been born "out of wedlock".

These were the children of "fallen women".

The mother-and-baby homes and the Magdalene Laundries were institutions run by the Irish state and the Catholic Church for such women.

The regime was cruel.

There are stories of women being forced to give birth without pain relief and in silence and then having the baby whisked away for adoption.

Many of the women ended up in the laundries - Catholic-run workhouses where 10,000 women and girls were forced to do unpaid, manual labour between 1922 and 1996.

The last Magdalene asylum in Ireland closed in Waterford in 1996.

A 2013 report found the Irish state was involved in the scandal.

As a little girl growing up in County Galway in the 1960s, Catherine Corless shared the classroom with the "home babies".

The town children were not encouraged to mix with them.

Once she saw another girl offer a fake sweet to a home baby.

"She said, ‘If you hand that girl an empty sweet paper, she'll take it,’" she recalls.

"So I wrapped up an empty sweet paper and pretended it was a sweet to the other girl and she grabbed it.

It was only in later years, I realised that those children never got any sweets - no treats whatsoever, not even at Christmas.

"My mind went back to that day and that little child who thought she was getting a treat and I would have laughed at her.

"That has horrified me since, it has haunted me really."

The Tuam home was one of 10 institutions across Ireland to which about 35,000 unmarried pregnant women were sent.

It operated between 1925 and 1961.

Conditions were poor and hundreds of babies and children died of natural causes: At the Tuam mother-and-baby home between 1925 and 1961, a child died nearly every two weeks.

After the Tuam home closed, a housing estate was built.

In the 1970s, two boys discovered bones and the local people built a shrine to what they believed were famine dead.

In 2011, Corless set out on a personal crusade.

She looked for the death certificates of the 796 children who had died at the home, for whom there were no burial records.

She paid for each death certificate herself.

She wanted to put up a plaque in their memory.

What she found made headlines across the world.

The skeletons of hundreds of babies and children lay in an unmarked mass grave.

It was a shame that the then Taoiseach Enda Kenny called "a chamber of horrors".

"We buried our compassion, humanity and mercy," he told the Irish parliament.

Bedsheets with the names of victims have been put on the shrine's gates

A public inquiry into Ireland's mother-and-baby homes was established in 2015.

It is due to report by February 2019.

Ms Corless remains saddened by the Catholic Church's response.

"If we could get an apology from the Pope when he comes that might help," she says.

The Church has said it is shocked and horrified by the discovery of the children's remains.

Ms Corless would like more.

"I'm saddened at those who preach and tell us how to live," she says.

This was a golden opportunity but they chose to protect themselves and to protect the institution that is the Church.

Lisa O'Hare knows more than most what it takes to raise the next generation of Irish Catholics.

The 41-year-old County Tyrone mother has seven children under the age of 12 - two of whom have special needs - and is expecting her eighth.

Three years ago, she helped set up the Rise of the Roses, a movement aimed at encouraging young women to consider "consecrated life" - becoming a nun.

Girls aged from 14 to young women in their 20s were taken to visit convents across Ireland.

"We wanted to open the girls' minds, to go and visit these religious sisters to see how happy and joyful they were in this calling," she explains.

"We were trying to open their hearts to answering the call from God, whether he was calling them to religious life or married life; both are equally important vocations.

"Obviously I am in the married vocation, but we wanted to create a culture of saying yes to God."

She says Rise of the Roses was an attempt to break stereotypical preconceptions about nuns and religious vocations.

“In this culture, if someone came home to their parents and said, ‘I’m thinking of becoming a religious sister,’ even their family and their friends would be really shocked, it’s so counter cultural.”

The full-time mother juggles family life with her part-time role with Human Life International, a group promoting traditional Catholic teachings on abortion, euthanasia, marriage and family.

She says she was devastated by the Irish abortion referendum result earlier this year, when two-thirds of the electorate voted to overturn the ban.

"Many of us described it almost like a death, " she says.

"We described it as a crucifixion.

"You have to endure the crucifixion and look forward with great hope to the resurrection."

She fears that Ireland has "turned away from God" in recent years and Catholics who try to follow the Church's teachings on social issues are becoming increasingly isolated.

Such secularism has entered the Church that people take or leave parts of the challenges of our faith, and those that want to live it authentically often feel that they are called radical or fundamentalists.

The Rise of the Roses was her attempt to rekindle the culture of consecrated women.

At the last official count, there were 5,730 sisters in Ireland’s 26 dioceses, outnumbering all the priests and brothers put together.

But with fewer younger women joining religious orders, nuns who retire from teaching and nursing posts are more likely to be replaced by lay people.

Many argue that the vow of celibacy puts young people off becoming nuns and priests, but Mrs O'Hare dismisses this.

"It is sacrificial, but every single Christian and Catholic is called to a sacrificial life," she says.

"My middle child had extensive brain surgery, so most people would think we're crazy for having any more children, that we've enough to contend with.

"My baby, Michael, has Down's Syndrome and yet we're expecting again, and that's because I have ultimate trust in Jesus and I know that he will guide me."

Mrs O'Hare believes the Catholic Church in Ireland has experienced a "perfect storm" in the last 20 years.

This individualist culture where it's all 'Me, what I need and what I can get from certain aspects of life.

"That has been catastrophic," she says.

However, she adds that storm also included "shocking" revelations about paedophile priests and mother-and-baby homes.

She says the abuse was "pure evil".

"The people who inflicted these terrible atrocities didn't only affect those directly involved, they have affected a generation," she says.

"They've affected the priests' and the religious [community’s] ability to communicate a message, because it has been absolutely undermined."

What is her hope for the future of the Church in Ireland?

"I'm so passionate about our nation, about our country, about the culture that we have.

"It's something that I hope to build up in my own personal way by providing children and a family and working hard in my small parish and community - we can do that from the grassroots up and everyone has to play their part."

She adds: "Ireland has faced many a trial and the faith has been under many an attack over the centuries and God has never let us down, so we will just continue with that hope in our hearts."

Between then and now lies a vast chasm.

From the visit of Pope John Paul II to the visit of Pope Francis, the change has been seismic.

Tremors have rocked Irish society, politics and culture.

Modern Ireland is unrecognisable to that of Pope John Paul II's 1979 visit.

Pope Francis will be aware of that.

Much is expected of the Argentine Pope, not least from the thousands of abuse survivors who will want an official acknowledgement of the Church’s role in their suffering.

The story of abuse and the Church’s response to that abuse leaves ugly scars.

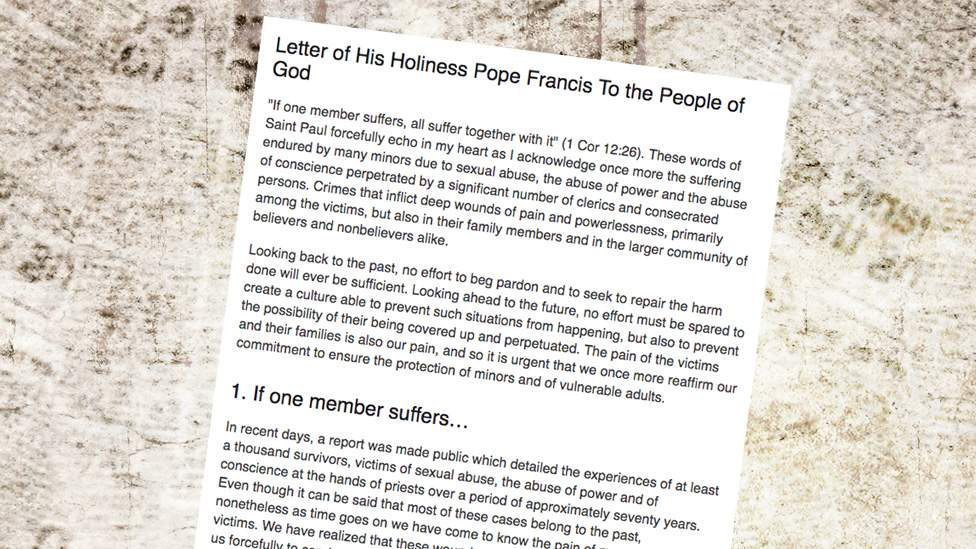

Days before his Irish visit, Pope Francis wrote a letter to all Catholics begging forgiveness for “our sins and the sins of others”.

“We showed no care for the little ones; we abandoned them,” he said.

The Archbishop of Armagh, Most Reverend Eamon Martin, says people “want to know that the Church accepts that abuse within the Church was systemic, that it was facilitated and that this will happen no more”.

What people want, he says, is to know that they and their children will be as safe in a Catholic church as they would be at home.

Despite all this, excitement for the papal visit is strong.

Pope Francis’s words could have a significant impact.

Although he will step off that plane on to the tarmac of a markedly different Ireland, like Pope John Paul II, Pope Francis is a charismatic figure.

He is also more nuanced than the Polish Pope.

His official stance on sexual ethics may be similar, but his tone is strikingly different.

Pope Francis is attempting to change the conversation from one focused on sexual ethics to one centred on social justice and a politically relevant version of the Christian gospel.

If that is a message he can deliver in Ireland this weekend, it may be the breath of fresh air needed to help halt the Church’s decline in this traditionally Catholic country.