The candidate floated above the crowds, carried on their shoulders.

The main commercial street in the south-eastern city of Juiz de Fora was packed for his rally. He wore a yellow T-shirt with green block letters - “My party is Brazil”.

It was 6 September, three weeks into the most unpredictable presidential campaign in Brazil’s recent history.

Jair Bolsonaro had given a thumbs-up to the crowd - smiling at chants of “the captain is back”. Suddenly he clutched his stomach with both hands. Grimacing in pain, he slowly slipped to the ground.

Bolsonaro had just been stabbed with a 20cm kitchen knife. A man called Adelio Bispo de Oliveira was nearly lynched by the crowd. The suspect would reportedly later tell police he had acted on “God’s command”.

Videos of the attack were watched over and over again by Brazilians.

Bolsonaro’s abdomen was punctured and he lost two litres of blood. But as awful as the attack was, it proved to be a turning point for his campaign.

Image posted by Bolsonaro's son Flávio on Twitter

“You have just elected the president,” his eldest son, Flávio Bolsonaro, wrote on Twitter. A defiant picture showed his father lying in a hospital bed in a blue gown, with tubes sticking into his nose. The candidate did his trademark gesture, pointing his fingers, like pistols.

Bolsonaro had been considered too extreme by many, with his broadsides against women, gay people, black people and even democracy, his violent rhetoric against his opponents and his nostalgia for Brazil’s military dictatorship.

But he was now the victim of an assassination attempt. The breaking news story was not covered by the media regulations imposed during the campaign.

Flávio Bolsonaro outside Santa Casa hospital

Under normal circumstances, Bolsonaro and his small Social Liberal Party (PSL) would only have been entitled to very brief TV campaign ads - just eight seconds. But now he was all over the airwaves.

“Look what a holy stab that was. It changed everything,” influential pastor Silas Malafaia recalls telling him in a hospital visit. “All people talk about is you.” His contenders were “dying of envy”. According to Malafaia, Bolsonaro chuckled but held back his laughter. It made his stitches hurt.

Being injured did something else. It meant Bolsonaro could not take part in televised debates against his rivals.

At first this was following clear doctors’ orders - he had suffered very serious injuries.

But things didn’t change even after doctors recognised his improvement and said it was his call - the surgeon advised that although he could not stand for long periods he could do a shorter debate while sitting in a comfortable chair. Bolsonaro's campaign pointed out that he still had health problems and discomfort from having a colostomy bag.

Bolsonaro avoided additional exposure when he was already leading in the polls. Brazilians elected a president in a run-off vote without ever having seen a face-off between the two final candidates.

So how did he get there?

In 1970, troops arrived in the scenic Ribeira Valley in the state of São Paulo, hunting for enemies of the military regime in the woods and farmland around the town of Eldorado.

It was the most violent phase of a dictatorship that had started six years earlier with a military coup against President João Goulart.

The soldiers in the Ribeira Valley were looking for Carlos Lamarca. The former captain had deserted the army a year earlier to join a leftist guerrilla group and became one of the leaders of the armed struggle against the regime. He had come to Eldorado to set up a training ground in the valley.

President Joao Goulart (L) and President Kennedy (R) leaving the White House, 1962

It was Bolsonaro’s home town - he was 15 years old. “[Lamarca] was in the region and injured six soldiers,” Bolsonaro recalled in a 2017 interview. "He took one of them... as a hostage, and then killed him with strikes of a rifle butt - cowardly.”

As the war between the military regime and left-wing guerrilla fighters came near his door, the young Bolsonaro chose his side.

“I knew everything in those woods and I passed on information to the soldiers about the places,” he said. He and other young men in the region offered guidance to the army to help find Lamarca’s hideaway.

The guerrilla managed to escape, but was killed a year later. As for the boy, he decided to join the army. At 18, Bolsonaro enrolled in the preparatory school for cadets.

It was the start of a military career that would mould Bolsonaro’s beliefs.

Our Lady of Guidance Church, Eldorado

He had been born into a family of six children, descended mostly from Italian immigrants - the surname came from his Venetian great-grandfather, initially spelled Bolzonaro. His father was a dentist, the only one in town, and his mother a housewife. They were not wealthy and rented a simple house by the Ribeira do Iguape river.

The young Bolsonaro used to go fishing on the river and extracted heart of palm in the woods to make some money. Palmito, as the inner core of palms is called in Portuguese, was one of his nicknames - he was long, lean and very light-skinned.

He helped his father produce dentures for his clinic. And he liked shooting birds with pellet guns and going on hunts for gold in areas that had been mined in the past.

Celso Luiz Leite and his wife Maria do Carmo Ferreira Leite

Those close to him remember him as a serious young man, a dedicated student. “He wasn’t the party type. He liked doing sports and going fishing,” says Celso Luiz Leite, 63, whose sister is married to one of Bolsonaro’s brothers. “A friend of his told me Jair always said he wanted to be the president of Brazil.”

Today the region mostly survives off its abundant banana plantations and some tourism. Bolsonaro’s siblings still live there and are a lot better off - his family now own a number of furniture and construction suppliers.

People in Eldorado hope that now he’s president, Bolsonaro won’t forget them.

“We have good expectations,” says Antonio Carlos de Melo Cunha, 64, who used to go to school with Bolsonaro. “If he stops all this stealing in politics it’s already an important mark. And I believe he may bring some benefits to our region.”

In 1977, Bolsonaro graduated from Brazil’s Agulhas Negras academy for army officers, three hours away from Rio, in the city of Resende.

The writing on the school’s facade summarises their philosophy: “Cadet! You will command. Learn to obey.”

There he quickly stood out as an athlete. His speed on the running track and strength in the military pentathlon team earned him the nickname of Cavalão (“Big Horse”).

His training continued at the army’s physical education school and then with the Paratrooper Brigade in Rio de Janeiro, where Bolsonaro settled. He rose to the rank of captain.

But then he did something officers were not allowed to do - he spoke out.

In 1986, he used an article in a news magazine to argue that colleagues were giving up their careers because of inadequate wages.

A year later, he came under investigation over graver allegations. The same magazine accused Bolsonaro and a colleague of a plot to plant small explosive devices in military bases - supposedly designed to make a commotion and pressure government officials into raising salaries.

Bolsonaro denied the plot.

A military council initially ruled that he should be stripped of his post but when his case was sent to the Supreme Military Court he was acquitted.

Despite that, his military career was effectively over. And his relationship with the media hadn’t started off well.

“He lost his position in the armed forces because of fallacies published by the press,” says journalist Waldir Luiz Ferraz, who has worked with him ever since.

“He stood no chance of pursuing a successful military career. So he was advised to go into politics.”

Brazil’s 21-year dictatorship came to an end in 1985 and a new constitution was proclaimed in 1988. It became known as the “citizens’ constitution”.

That was also the year Bolsonaro was elected to Rio’s city council.

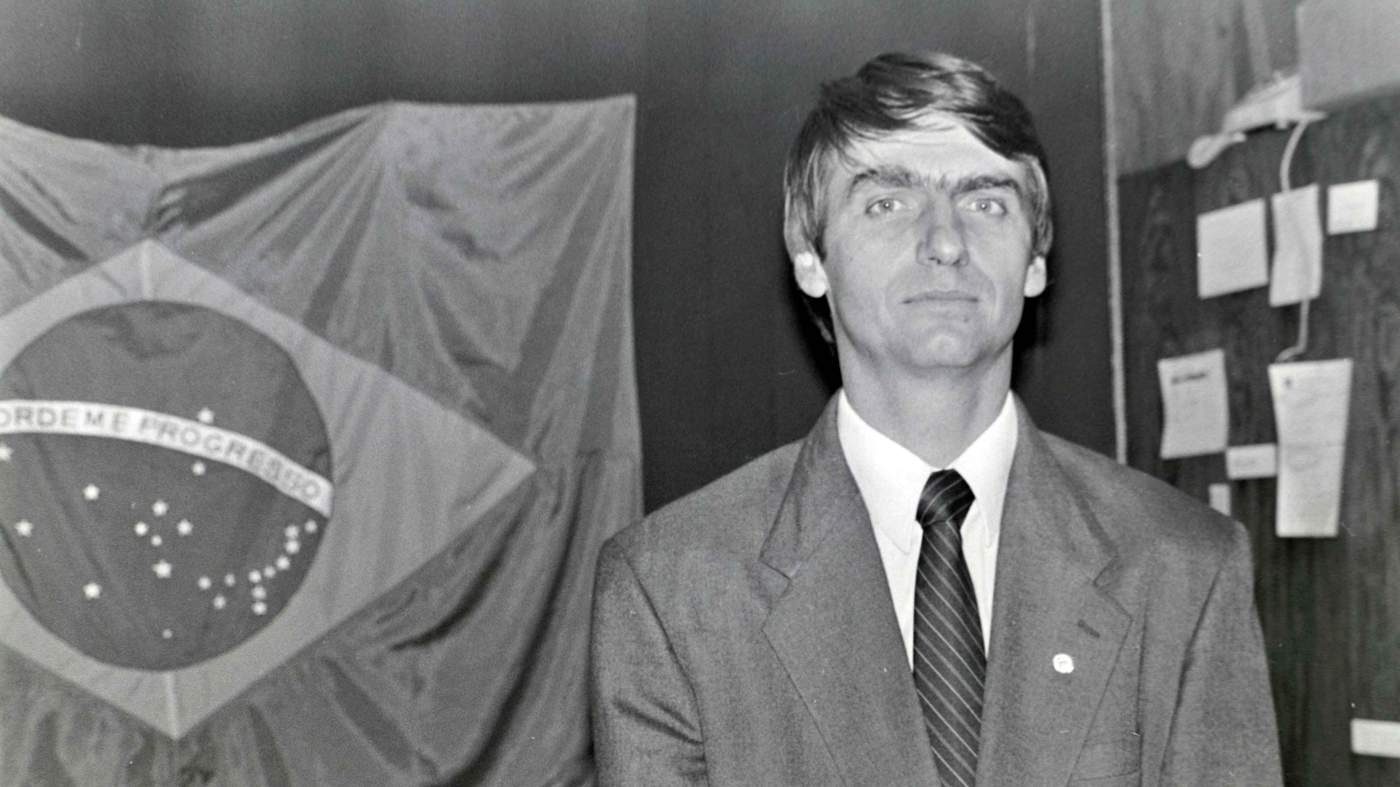

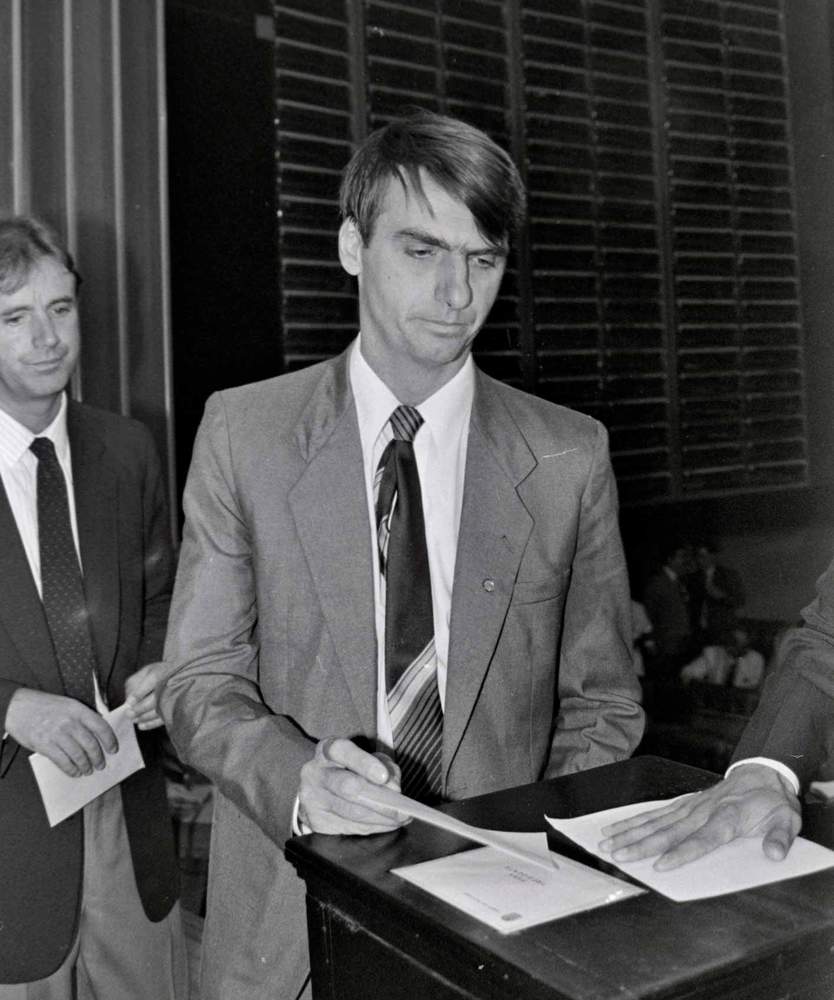

Congressman Jair Bolsonaro, 1991

The former captain’s outspoken demands for higher pay had given him fame among his peers, and earned him support from the military community.

“The campaign took lots of hard work,” recalls Ferraz, who did his public relations from then on. “We’d always be up at dawn slipping leaflets under the doors of military houses.”

In 1991, Bolsonaro moved on to the lower house of Congress, again boosted by voters from the military.

Congressman Chico Alencar entered Rio’s city council in the same year as him and came to have a parallel trajectory in Congress, but on the left.

“From the beginning, Bolsonaro emerged as a dictatorship nostalgic and a defender of the military. He was obsessed with attacking what he referred to as subversives from the left,” recalls Alencar, a history teacher as well as a politician.

In 1993, Bolsonaro rose to the Congress podium to proclaim: “I am in favour of a dictatorship. We will never resolve serious national problems with this irresponsible democracy.”

He was depicted on the front page of O Globo, the Rio newspaper, as a dinosaur in army boots - Stupidosaurus, according to the cartoon.

Front page of the O Globo newspaper, 1993

“His views were always very narrow, sectarian,” says Alencar. “He was seen as an eccentric figure - rude, authoritarian, always saying the same things.”

Bolsonaro has been married three times, and has five children. His first wife, Rogeria Bolsonaro, was elected a councillor in Rio shortly after he went to Congress.

Bolsonaro with three of his sons (L-R): Flávio, Eduardo and Carlos

His three older sons, Flavio, Carlos and Eduardo, have followed his steps to form a Bolsonaro political clan. They were all elected lawmakers at early ages. Carlos, now 36, became a city councillor aged 17.

“He used to joke and tell me that one day the Bolsonaros would be bigger than [my] PSOL,” says Alencar, referring to his own small Socialism and Liberty Party.

It was 2003, Maria do Rosário’s first year as a deputy in Congress, and she had a press interview about her work heading a commission that fought the sexual abuse of children.

Bolsonaro was being interviewed before her, inside the Congress building. He was arguing for the reduction of the age of criminal responsibility, based on a recent case of a teenager who had murdered a young couple.

But his words had a belligerent tone that shocked Maria do Rosario, she recalls. According to her version, she told him he should calm down, arguing that violence begets more violence. He was enraged.

Bolsonaro and Maria do Rosário during an interview on RedeTV!, 2003

“Are you calling me a rapist?” he said, turning to the camera. “She’s calling me a rapist!” And he looked at her: “I would never rape you because you don’t deserve it.”

She told him she would slap him if he made any such move. “Do it and I will slap you back,” he shouted, repeating the sentence six times as he pushed her and called her vagabunda - a whore.

The episode was one of a long list of past outbursts seized on by critics of Bolsonaro during the presidential election campaign.

Bolsonaro has said he was “proud to be homophobic” and that he’d rather see a son die in an accident than appear with a “moustached” partner.

He said he wouldn’t hire a woman for the same salary as a man since they get pregnant.

He described “quilombolas”, as descendants of African former slaves are known, as people who “did nothing” and were too fat “even to breed”, criticising how much they cost the government in welfare programmes.

Bolsonaro said that Brazil would be a better country if the dictatorship had killed more people, including former President Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

He had also vowed he would shut down Congress “on the same day” if he were ever elected president, referring to parliament as “useless” in a 1999 interview. “Let’s do the coup, already. Let’s go straight to the dictatorship,” he said at the time.

Who would elect a president like that, his opponents asked.

Pro-Bolsonaro Women's March, 2018

But he struck a chord with supporters - his unfiltered remarks conveyed a frank, no-nonsense image. Like US President Donald Trump, they saw him as someone who spoke his mind - and at times said things many people thought, but were too afraid to say.

“Bolsonaro managed to capture a social feeling that was out there,” notes sociologist Esther Solano, a professor at the Federal University of São Paulo and organiser of the book of essays Hate as Politics: The Reinvention of the Right in Brazil, published in Brazil in 2018.

“When he makes homophobic or racist jokes, he knows this will raise controversy, but he also knows that many in his ‘base’ will nod approvingly,” says Solano, underlining how conservative many people in Brazil are when it comes to gender, race and class divisions.

Electing a president like Bolsonaro might not have been possible a few years ago in Brazil, she says - but after Trump, a new way of doing politics was established.

Anti-Bolsonaro's Women's March, 2018

Emphasis on the politically incorrect and on controversy became a form of campaigning. “Trump opened the door to others who wanted to follow,” says Solano.

During the campaign, feminist groups organised under the motto #EleNão, “Not Him”, urging voters to choose other candidates. Huge protests were held a week ahead of the first round of votes in over a hundred Brazilian cities.

Bolsonaro’s allies say the media is hostile towards him and distorts his words, taking them out of context.

Joice Hasselmann, a former TV and radio presenter who ran for Congress in 2018 under Bolsonaro’s umbrella, used to think he went too far - until they met four years ago and there was “immediate empathy”.

“He’s very different from what you think from what you see on the news,” she says. “He is a big man with a boy’s heart. He’s very sweet and humorous.

“Jair is not a good communicator. Sometimes he gets trampled by his words.”

Bolsonaro with Joice Hasselmann

Lawmaker Alberto Fraga, who was in the same class as Bolsonaro at the army’s physical education school and has shared much of his time in Congress, says “people exaggerate”.

“His positions are very clear. But they are also very firm. If he doesn’t agree with something, that’s that. He doesn’t even let the conversation go on,” Fraga says.

Congressman Alberto Fraga

He describes him as a playful and popular character, who would stop to take pictures with fans in Congress and always had lunch in the cafeteria along with the general staff.

Fraga says he witnessed the row between Bolsonaro and Maria do Rosario back in 2003. “She’s the one who called him a rapist. She’s the one who said she would hit him. He said he would hit her back,” he says in his defence.

Bolsonaro during a debate in the Brazilian parliament, 2016

“He is like a snake,” says his long-time PR agent Waldir Luiz Ferraz. “When he is attacked, he attacks back. As long as he’s not attacked, he’s really easygoing.”

But Do Rosário denies ever having called him a rapist, and says she still suffers attacks from his supporters on the internet.

“He adopted the same attitude as men who attack women and then say they are to blame, saying they did it because she deserved it. I’m not willing to accept that,” she says.

“He wins discussions by shouting, and that’s how he got elected.”

In a green T-shirt, with a backdrop of bushes and clothes lines covered with washing, Bolsonaro started an impassioned campaign speech as birds chirped in the sunny backyard of his home.

It was a week before the final vote of the 2018 presidential elections.

He shouted into a smartphone while someone filmed him with another. His audience was 500km away from Rio - thousands of followers gathering in São Paulo’s iconic Paulista Avenue.

Paulista Avenue

“This time, the clean-up will be even greater. This group, if they want to stay, will have to abide by our laws,” he roared.

“These red outlaws will be banned from our homeland. Either they go overseas, or they go to jail.”

The speech was rapidly shared, and went down with dread or delight, depending on which side of a divided Brazil was watching.

The “reds” were the Workers’ Party - the PT - and demonising the left-wing group was a key part of his campaign strategy.

Heavy unemployment, economic crises, escalating violence and a series of corruption scandals that discredited the whole political system all provided fertile ground for Bolsonaro.

“We have to change all this,” became his informal trademark phrase.

“This” included the PT. After winning four presidential elections, the party was tainted by corruption scandals revealed by Operation Car Wash, the investigation which has uncovered a series of kickback schemes involving a number of political parties.

To many Brazilians, enthusiasm for the period of growth under former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva has long been forgotten, and the PT has become synonymous with corruption and economic crisis as inequality and poverty levels rose.

Lula himself was charged with corruption and jailed for 12 years in April 2018. He denies the charges.

The economy derailed under Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, who was impeached in 2016 for breaking budget laws. She denies any wrongdoing.

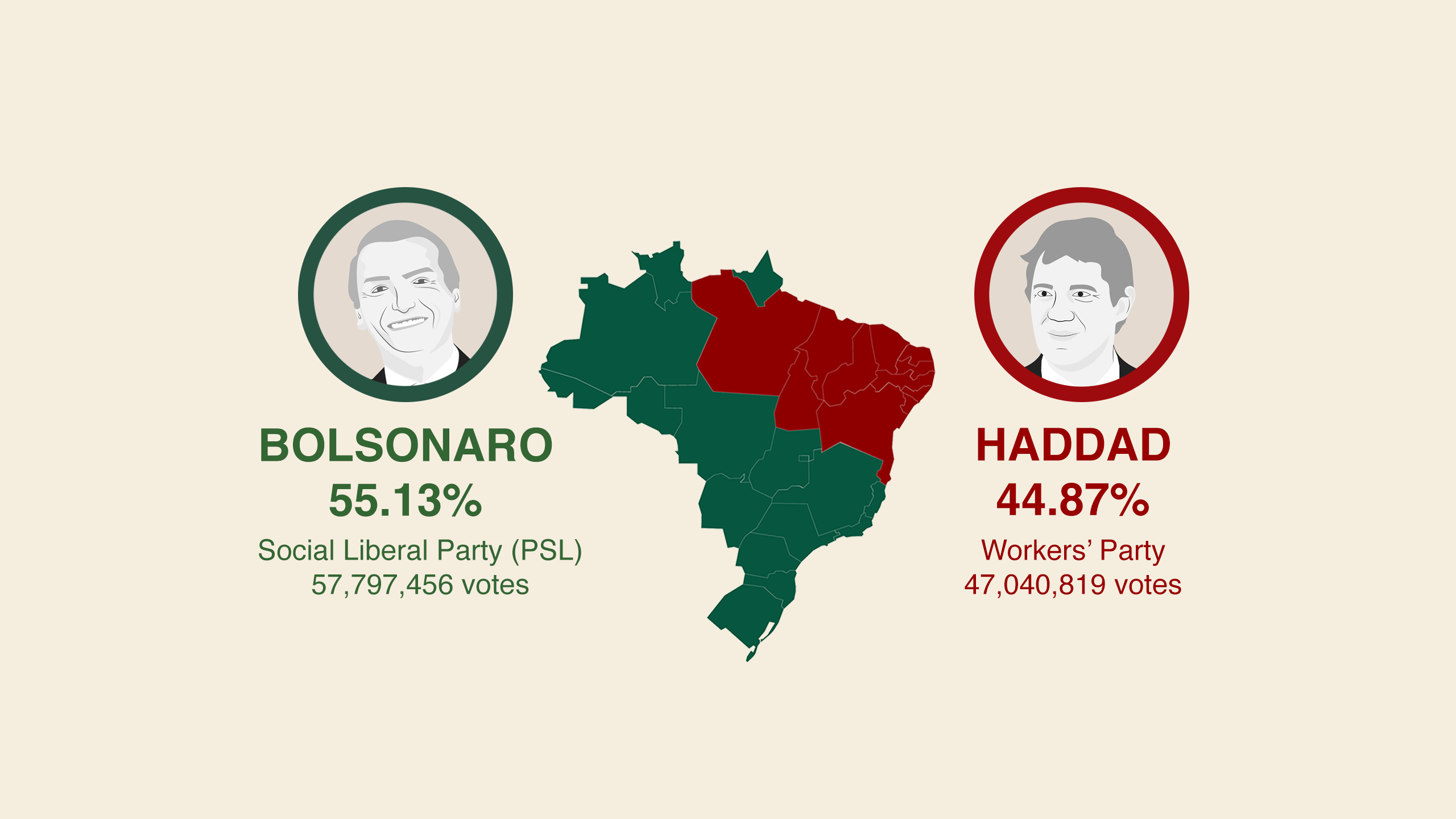

The PT offered former São Paulo mayor Fernando Haddad as candidate for 2018’s election - but a big chunk of voters just didn’t want the PT back.

Presidential candidate Fernando Haddad (C)

Rousseff had been ousted in a controversial process that the left called a “parliamentary coup”, and which deepened social divides between left and right.

The mass protests calling for her to be removed were a platform for right-wing groups in Brazil. They grew and became organised, adopting the patriotic green and yellow of the Brazilian flag.

Still, Bolsonaro was running for a tiny party and was seen as an unimportant politician who in 27 years in Congress had only approved two minor bills and had rotated between different parties.

His ideas were considered too extreme for a viable candidacy at first, but that changed in a time of disillusionment. Other centre-right candidates failed to gain support, and Bolsonaro started to appear as the only right-wing candidate who could beat the Workers’ Party.

“Brazilian democracy opened a number of doors and Bolsonaro was able to walk through,” says Timothy Power, director of the Brazilian Studies Programme at the University of Oxford.

“You have to give him credit for having very good political instincts. He knew this was the year. His support base was very narrow, but he smelled the blood in the water after the impeachment.

“The political system was vulnerable to a clever populist who could create an anti-system and an anti-PT message.”

Bolsonaro ran a highly unconventional campaign. He had a small party machine and a paltry campaign budget.

He resorted to the power of social media and his knack of speaking directly to his voters in blunt, simple language. Press reports outside Brazil nicknamed him the “Trump of the Tropics”.

With a multitude of Tweets and Facebook live videos, he built a solid base of followers - called “Bolsominions” by opponents.

He talked about everything - from politics and the electoral race to his recovery in hospital and attacks against the “fake news” media and his opponents.

Microphones placed on top of a bodyboard at a press conference held at Bolsonaro's home

There were snapshots of his everyday life - like a picture of him seated at a messy breakfast table covered in breadcrumbs, using a can of condensed milk (a national favourite) to spread on bread.

“In a period where politicians were being rejected left and right, he got some brownie points for conveying authenticity and for having a very simple set of messages: ‘I’m against corruption. I’m against politicians. I’m against crime, drugs and gangs.’ These things resonate with the public,” says Power.

But critics complained about a wave of “fake news” during the campaign, with rumours swirling online - particularly on WhatsApp - about his opponents.

Bolsonaro knew things were going well. At every town he travelled to, he was greeted by crowds of frenzied supporters at the airport.

I was at one of these receptions and saw him carried on his voters’ shoulders to the chants of “myth”, wrapped in a presidential sash, seven months ahead of the elections.

His candidacy was backed by supportive groups in Congress, notably the BBB - the Bible, Bull and Bullet triumvirate - representing the evangelical churches, agribusiness and pro-gun lobbyists.

Bolsonaro pledged to ease gun control, so that “honest citizens” could own weapons, and to interrupt demarcation of indigenous land reserves, which scored points with the rural sector.

And he embraced a conservative moral agenda together with evangelical groups in Congress, standing for the values of the “traditional family” and “the innocence of children”.

This alliance had been strengthened when Bolsonaro and pastors in Congress joined to condemn a package of educational material that the Dilma Rousseff government tried to introduce in 2011, to tackle homophobia in schools. They called it the “gay kit” and said it would teach children how to be homosexuals. The material ended up being dropped.

Bolsonaro was raised a Catholic, but was symbolically baptised in Israel’s Jordan River by an evangelical pastor in 2017. His campaign motto was: “Brazil above all, God above everyone.”

“We share the same views and the same agendas,” says pastor Silas Malafaia, who performed Bolsonaro’s wedding ceremony to the now first lady Michelle Bolsonaro in 2013.

First lady Michelle and the president

“We’re all against abortion, gender ideology, gay marriage. The left-wing governments were attacking our moral values,” he says.

As the race progressed, Bolsonaro started to appear as the only right-wing candidate who could beat the Workers’ Party.

Winning over business leaders was largely down to his economic guru, Paulo Guedes, a free-market advocate who earned his doctorate at the University of Chicago.

Guedes, now minister of economy, made Bolsonaro appeal to Brazilians who wanted to see liberal economic policies implemented. Bolsonaro himself admits he doesn’t understand economics.

“He knows his limitations. He’s a very humble and simple man,” says pastor Malafaia.

After Bolsonaro won, he recalls his words to him.

“I’m like the Beetle that made it into a Formula 1 race and won. The improbable of the improbable,” he told the pastor. They both laughed.

On 28 October, as soon as Bolsonaro learned he had won, he did a Facebook live.

At his home in Rio, he sat with his wife on one side, a sign language interpreter on the other, and carefully chosen books on the desk: The Bible, Brazil’s constitution, World War II memoirs by Winston Churchill and a collection of articles by Olavo de Carvalho, a self-taught philosopher who has become a guru to Brazil’s right-wing.

He thanked God, the medical team that had “operated a miracle” in saving his life, and his loyal followers on the internet. He hadn’t gone for the presidency out of personal ambition, “but out of the certainty that we could change Brazil’s destiny,” he said.

Maintaining a stern expression, he declared: “God clearly has a purpose for me and for all of us in Brazil.”

He then prayed in a circle with his allies. Only after that did he make an official, nationwide TV-address.

Bolsonaro’s first moments as president-elect reflected his strong allegiance to his followers both on social media and in evangelical groups.

But in an attempt to dispel fears raised by his controversial history, he vowed to respect the constitution and democratic rule, and to govern for the country as a whole.

“We will offer you a decent government, which will truly work for all Brazilians.”

Outside his house in Rio, on the beachfront, the party exploded. Supporters lit fireworks, sang the national anthem and wrapped themselves in the Brazilian flag.

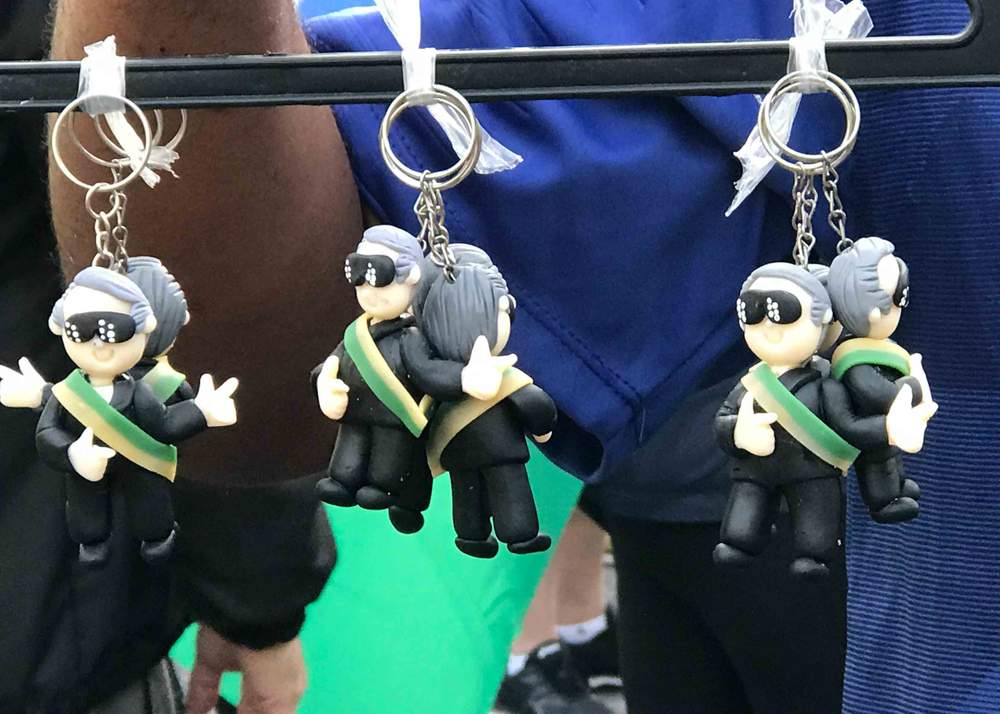

Vendors sold inflatable dolls depicting former President Lula in a black and white prison uniform, and key rings showing Bolsonaro wearing sunglasses, a presidential sash and pointing his fingers.

“We are just so thrilled that he won. We defeated communism!” a woman told me in the middle of the crowd outside, waving a flag and wearing a T-shirt with the slogan BolsoMito - “BolsoMyth”.

Over the past months, Brazilians have watched as Bolsonaro made his first moves as a president who promised to change the way politics is conducted in Brazil.

One by one, he announced his ministers on Twitter. He had promised to reduce his cabinet from 29 to 15 ministries - he ended up stopping at 22 in total.

The cabinet he built around him reflects his views about the military, his moral values and his contempt for the left-wing governments of the PT.

It includes a Ministry for Women, Family and Human Rights, led by a female, anti-abortion evangelical pastor; an environment minister who says global warming is a “secondary issue”; and a foreign minister who has promised to “help Brazil and the world liberate themselves from globalist ideology”.

Minister for Women, Family and Human Rights Damares Alves

After South America’s wave of left-wing governments in the mid-2000s, Bolsonaro’s foreign policy now signals an alignment with an emerging global right.

Trump called to congratulate Bolsonaro straight after his election and Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán travelled to the presidential inauguration on 1 January.

As well as Bolsonaro himself, seven of his ministers and his vice-president, Hamilton Mourão, have military backgrounds.

First Lady Michelle Bolsonaro (L), Jair Bolsonaro (C) and Vice-President Hamilton Mourão (R) during their inauguration ceremony

Appointed head of the presidential office for national security, retired Army General Augusto Heleno Ribeiro Pereira says in no way does this make it a “military government”.

“I hope people understand that he is a president for all Brazilians,” says the general, who commanded a UN peacekeeping mission in Haiti and is an old friend of Bolsonaro’s.

Newly appointed Chief of Staff Onyx Lorenzoni (L) and head of the Office for National Security, retired army general Augusto Heleno (R)

Bolsonaro takes on the post with huge challenges ahead for Brazil. The country has seen a sluggish recovery from recession and growth is expected to stay at 1% this year. Its debt is among the highest in any emerging economy.

Unemployment has reached 12 million and crime rates have been rising year after year - with 63,000 homicides across the country in 2017.

Bolsonaro has pledged to implement pension reform to reduce government spending and achieve fiscal balance. But this is a highly unpopular measure that requires two-thirds support in Congress - and he has kept to a campaign promise of not distributing seats to potential allies in parliament, which may create challenges for governance in the future.

“He will now have to make alliances, form coalitions, work with different parties on the floor of Congress,” says Timothy Power.

If part of Brazil has high hopes for the former captain, another part is deeply worried about how his ideas will play out into policies.

On his first day in office, Bolsonaro adjusted Brazil’s minimum wage, with an increase that was slightly lower than expected - reflecting new inflation estimates. He made it harder to create reserves for indigenous communities and descendants of slaves. He removed any mention of LGBT concerns from national human rights directives.

Bolsonaro receives the presidential sash

Brazil’s stock market closed at an all-time high on the next day, after ministers reinforced their pledge to privatise state-owned companies and with hopes of a turnaround in Latin America’s biggest economy.

Areas of special concern include the environment and the protection of the rainforest and of Brazil’s indigenous people, human rights, social benefits, education, and the freedom of press, schools and academia. With his attacks against the “fake news media” and pledges to tackle “political indoctrination” by school teachers, there are fears of restrictions in freedom of thought.

There is also anxiety about whether his government could impact the rights of women, black people, LGBT people, and indigenous people. During the campaign he said minorities would have to “bow to the majority… or disappear”.

Crowds gather for Bolsonaro's swearing-in ceremony

“A campaign is a campaign,” says General Augusto Heleno. “Now it’s important to think positive, especially with the situation Brazil is in. The country was put on the verge of the abyss economically, politically and socially. We need to rebuild Brazil.

“I hope he may surprise the part of the population that did not vote for him.”

Correction: This story has been amended to reflect that the minimum wage was not reduced; it was increased by a slightly lower than anticipated amount.