On a cold night in February, residents of the battle-weary city of Srinagar woke up to the noise of fighter jets buzzing in the inky black skies.

War, many feared, was now just a shot away.

Residents of the city in Indian-administered Kashmir had begun stocking up on food. Petrol pumps had run dry. Hospital doctors were told to stockpile medicines. Anxious residents talked about building bunkers in their gardens. A prominent politician rued that he had bought a house near the airport, which now didn’t seem like a “good idea”.

Within days, Indian Mirage 2000 fighter aircraft were crossing deep into Pakistan.

An Indian Mirage 2000 aircraft on a practice run

India said the jets - armed with laser-guided bombs - were targeting a militant training camp near Balakot in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The air strikes were the first launched across the LoC (line of control) - the de facto border that divides Kashmir - and into Pakistan since a war between the two countries in 1971.

Conventional wisdom rules that nuclear-armed neighbours should tread carefully.

This policy was now being upended by India’s Prime Minister, Narendra Modi.

With characteristic bravado, the 68-year-old leader had ordered the strike as a “fitting, jaw-breaking response” to a deadly attack on Indian security forces in Kashmir earlier in the month. Modi told people he had given the army a “free hand”.

“The blood of people is boiling,” he said at one meeting. At another, he said: “I feel the same fire in my heart that’s burning inside you.”

Kashmir is the battleground of a protracted, debilitating rivalry between India and Pakistan.

Both sides claim all of the breathtakingly scenic Muslim-majority region, but control only parts of it. Each side feels threatened by the other. They have fought two wars and a smaller conflict in the region.

The latest “provocation” to India had been dire enough. On 14 February, a minivan packed with explosives was driven into a convoy of 78 buses carrying Indian paramilitary troops on a heavily guarded highway, about 19km (12 miles) from Srinagar.

The blast killed 46 troops, the deadliest attack on Indian forces in the region in decades. Pakistan-based militant group Jaish-e-Mohammad promptly said it was behind the attack.

February 2019: Wreckage from the attack which killed 46 Indian troops

Modi’s response upped the ante.

His party, the BJP, has always maintained that “nationalism, and national unity” are an “article of faith” in the party. Modi has energised the base with his muscular, unabashed nationalism.

Modi’s supporters believed he had kept his word and delivered a “crushing blow” to Pakistan.

The truth, however, was more complicated.

Less than 24 hours after the air strike, Pakistan shot down an Indian fighter jet in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and captured an Indian pilot. With both sides under immense pressure to calm tensions, Pakistan offered to release the pilot. A day later, Wing Cdr Abhinandan was returned to India.

A man watches the televised release of Indian Wing Cdr Abhinandan

At home, Modi wasted no time moulding the narrative to his own advantage.

“The country is in safe hands,” he announced.

It was a victory for Modi in more ways than one.

His approval ratings, which had declined after a series of setbacks in state elections, recovered appreciably.

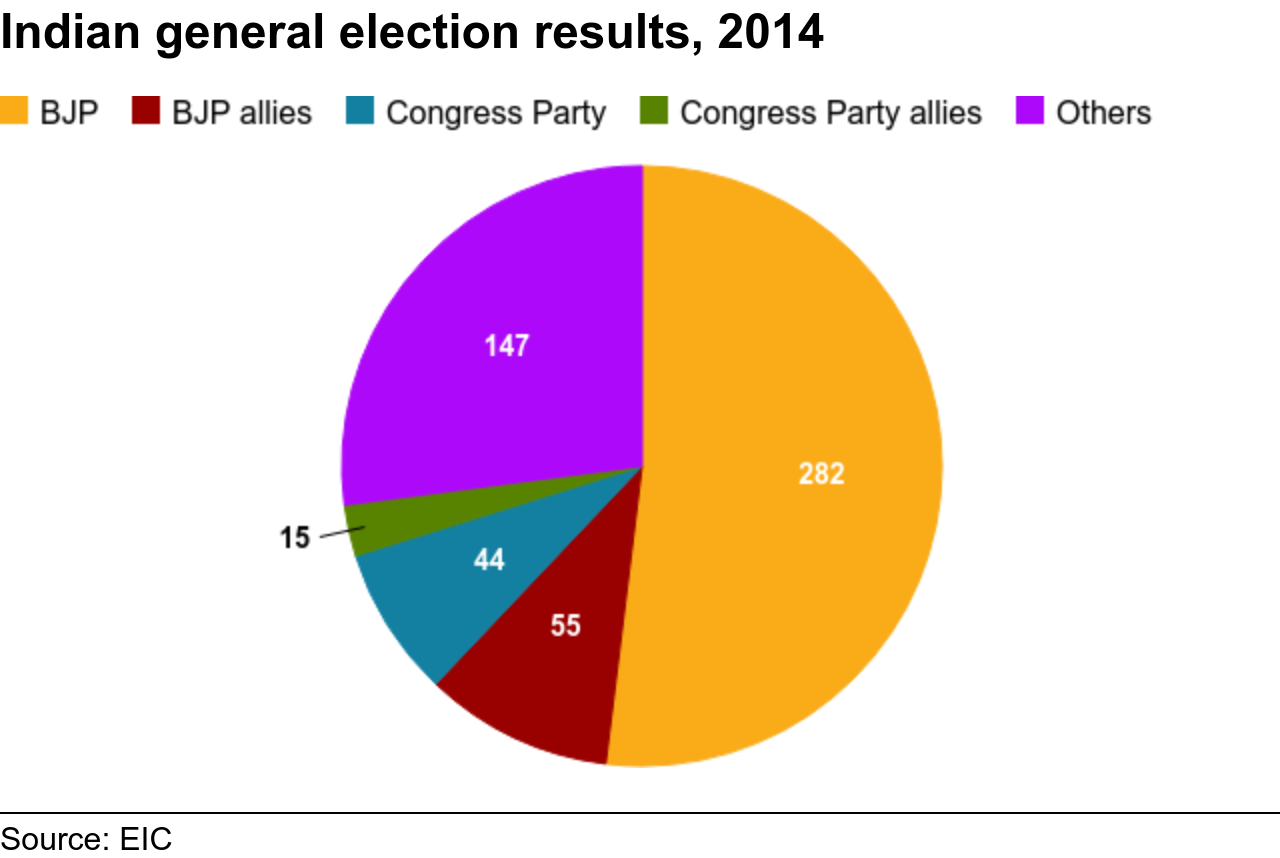

Modi had swept to power in 2014, leading the Hindu nationalist BJP to an unprecedented win. It was the first time since 1984 a party had won an absolute majority in a general election.

But despite the massive mandate, the verdict on Modi’s performance has been mixed.

There have been some gains – more roads, rural works, cheap cooking gas for the poor, village toilets, a uniform sales tax, a promising health insurance scheme which could end up benefiting 500 million families, and a new bankruptcy and insolvency law.

But the economy is underperforming. India’s farms, where most of its people work, are beset by a crisis of low crop prices. Unemployment is rising, and a controversial currency ban ended up hurting the poor.

Socially, the BJP’s strident Hindu nationalism has left the country polarised and minorities nervous. India is in the grip of a fake-news epidemic, partly due to cheap phones and data. Some dissenters have been labelled as “anti-nationals” and thrown into prison.

Modi has now won a second general election.

In some ways, it has been a referendum on the man himself. Many believe he wants to fashion India in his image - forcefully nationalist, socially conservative, openly patriotic.

For nearly 40 days in April and May, more than 600 million people have voted in 543 parliamentary seats in a marathon staggered election. It has been the biggest, longest and possibly most expensive ballot ever.

For one of India’s leading public intellectuals, Pratap Bhanu Mehta, it has been a “high stakes election with very low expectations”.

Has this election been, as some have said, “a battle for the soul of India”?

It's a bright day in March. Ranjanben Dhananjay Bhatt’s election campaign swings through the sun-baked streets of Vadodara, also known as Baroda, in Gujarat state in western India.

Fifty-six-year-old Bhatt is the BJP’s candidate for the seat.

She stands atop a shiny black jeep, her hands folded in a traditional Indian greeting.

Knots of men, women and children gather on the road to welcome her. They shower her with marigolds, bless her with prayers and offer homemade sweets and juice. They crowd verandahs and rooftops and cheerfully return the victory sign Bhatt flashes at them.

The streets are awash with saffron, the BJP’s signature colour. Motorcycle outriders wearing saffron turbans, scarves, caps and bandanas, lead the way. A flatbed truck with a smiling DJ plays upbeat music. Firecrackers burst.

In this merry festival of cacophony and colour, the air is thick with cries. They invoke one man.

“Modi, Modi, Modi,” young party workers chant in frenzied unison.

Modi’s face is emblazoned on T-shirts, caps, campaign hoardings and car stickers. He is everywhere, except in body - BJP workers are not sure whether he will find time to campaign in the seat.

“Modi is not contesting here. But he’s larger than life, and a vote for me is also a vote for Modi,” says Bhatt, an indefatigable campaigner.

In 2014, Modi won Vadodara by a mammoth 570,128 votes. He vacated Vadodara after winning a second seat in Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh (candidates can stand for more than one seat in Indian elections, and choose which one to take up if successful).

Bhatt, a former municipal councillor and a deputy mayor, swept to victory in the by-election a few months later.

Ranjanben Dhananjay Bhatt is the BJP candidate in Vadodara

In this BJP heartland, it is hardly a fight. The party has been in power here since 1996, and the opposition these days is pretty much invisible.

“This election is not about my winning, but the margin of victory. I am aiming to win by at least 600,000 votes and set a new record in Gujarat,” says Bhatt. Two months later, she will go on to win a convincing victory.

“Everything we do here is finally dedicated to Narendra bhai [brother]. Votes here are given to Modi. Gujarat is his birthplace and Vadodara is his workplace.”

Surprisingly little is known about the man who became India’s most powerful politician.

Modi was born the son of a tea-stall owner in Vadnagar, a grubby town some 200km (124 miles) from Vadodara.

According to one biographer, Modi did not have any special bond with either family or friends in Vadnagar and “virtually abandoned” the place in his youth.

As a teenager he was married in a traditional ceremony - a fact only confirmed in 2014 when he filed his election nomination papers. He lived with his wife, Jashodaben, for just three years.

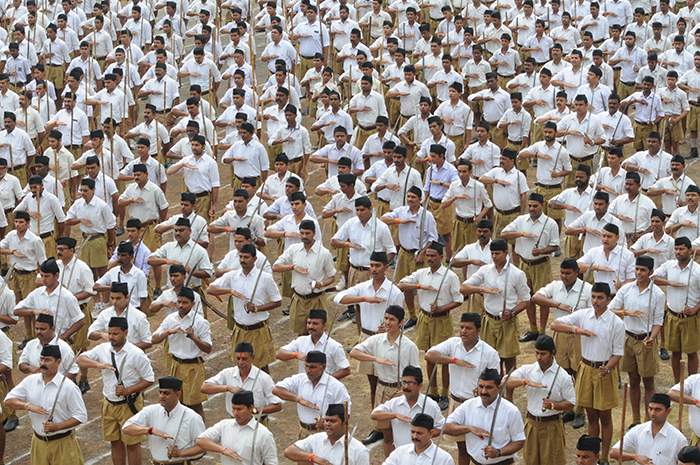

Early in his life, Modi joined the right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), widely regarded as the parent organisation of the BJP, and became a full-time worker.

RSS volunteers on parade in Bhopal, 2015

The RSS (which translates as National Volunteer Corps) was founded in 1925 and believes in the unity and protection of India’s majority Hindus. The organisation does not present itself as primarily political - its mission statement “emphasises culture and patriotism”, according to one study.

Nevertheless, the RSS has been the mainstay of Hindu nationalism since the days of British rule. Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in 1948 by a former member.

Today, the RSS has some 6,000 full-time workers. Some two million people participate in nearly 80,000 branches (known as shakhas) across India.

The BJP is a political affiliate of the RSS. It believes in Hindutva, an ideology seeking to establish the supremacy of the Hindus and the Hindu way of life.

During his early days with the RSS, say BJP workers, Modi lived for extended periods of time in Vadodara, sharing an austere one-bedroom RSS-owned property. “He would sometimes go around on a bike, meeting workers. He knows every street here, and he still has friends in the city,” says one party official.

Modi earned his spurs as a business-friendly, efficient chief minister during the 13 years he ruled Gujarat before moving to Delhi in 2014.

He was credited with making Gujarat an economic powerhouse, although the success of so-called “Modinomics” is a subject of keen debate among economists.

Modi was also accused of not doing enough to stop religious riots in 2002 when more than 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed. The violence was sparked by a train fire in the town of Godhra in which 60 Hindu pilgrims died. The fire was widely blamed on Muslim arsonists.

More than 1,000 people were killed in the Gujarat riots of 2002

Modi was named leader of the BJP in 2013. A year later he became prime minister.

His supporters see him as a hard-working, no-nonsense doer who does not “pamper the minorities”, alluding mainly to India’s 170 million Muslims.

They say he is a self-made man with humble roots, and contrast him with what they describe as the entitled and privileged Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, which has led the main opposition Congress party and ruled India for nearly half a century.

Priyanka Gandhi is the latest member of her family to become involved in the Congress party

“Modi is more popular than the BJP here. He’s a phenomenon. He was Gujarat’s most successful chief minister, and now he’s India’s tallest leader. Gujaratis are proud of him,” says a senior BJP official.

Amit Dholakia, a professor of political science in Vadodara’s MS University, says Gujarat has a long history of political Hinduism, which has helped Modi. But he adds:

“Modi understands that political Hinduism has its limitations because of divisions among the Hindus. Even in Gujarat, the BJP has never got more than 48% of the popular vote. So now he talks more about nationalism and development. Hindutva is a campaign filler.

“Modi is more of a pragmatist than an ideologue. He loves power. And the people here love him.”

Ambarish Nag Biswas was returning home from work near the eastern city of Kolkata on a balmy November evening in 2016 when his mobile phone rang.

It was his friend, and he sounded panic-stricken.

“Narendra Modi is on TV, and he’s taking away our money!” he shrilled.

“What do you mean?” asked Biswas.

His hyperventilating friend calmed down and explained.

Prime Minister Modi had announced that his government was abolishing high denomination notes. In four hours, the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes would be banned from circulation.

These two notes accounted for more than 80% of the currency circulating in India’s sprawling and messy cash-driven economy (500 rupees would buy seven litres of petrol in Delhi).

The drastic move, according to Modi, was intended to crack down on corruption by exposing billions of dollars in unaccounted-for wealth, which would now have to be presented to banks to change into the new currency notes.

It was also intended to help resolve the problem of counterfeit currency, and to meet the long-held aspiration of successive governments to move India away from a cash-dependent economy (the shadow economy, according to the World Bank, makes up a fifth of India’s GDP.)

That night Biswas remained wide awake.

Ambarish Nag Biswas

The 48-year-old, who worked for a dairy farm, had 24,000 rupees stashed away at home for emergencies.

Now he had to go to a bank, deposit the defunct notes, and withdraw fresh currency for his family. His wife, Rinku, was a homemaker, and his daughter, Saborni, was in high school.

When Biswas arrived at the bank the next morning, it was shut. A huge crowd had gathered, and nobody quite knew how the money would be exchanged.

Biswas queued all day without success. The next day he tried another bank where he had a separate savings account, but the queue was even longer.

He returned to the first bank. Suddenly, he heard a commotion.

An elderly man in the queue, with a walking stick and a plastic bag containing his cash savings and bank papers, had collapsed from exhaustion. He had been standing under the boiling sun for hours.

Biswas rushed ahead, picked up the man and, flagging down a car, took him to a hospital. Two hours later, the man had still not regained consciousness.

“I had lost two days at work standing in the queue. I still hadn’t been able to exchange and get money.”

He called his boss and asked for another day’s leave.

After queuing eight hours without food and water, Biswas deposited his notes, but managed to withdraw only 2,000 rupees. The banks were fast running out of cash.

“It was strange. There were only people like us in the cash queues. Where were the rich and influential who were supposed to be hoarding cash?” he says.

Modi’s announcement had plunged India into chaos.

Cities and towns were filled with panic-stricken people who were thronging banks to deposit money and withdraw lower denominations.

Cash machines ran dry. There were stories of people burning sacks of illegal cash and of people unable to pay for cremations and hospital admissions.

A man was said to have walked into a mobile phone store near Delhi with three million rupees in expired cash, offering to buy its entire stock of iPhones.

A politician in Bihar was reported to have spent 20 million rupees on gold ornaments. A dengue patient settled his hospital bills in coins, since bills were in short supply.

There was what was called a thriving “discount scam” where people offered to buy scrapped notes for less than their value, before laundering the expired money.

Reports said more than 100 people had died of heart attacks in the bank queues.

For Biswas, and the many others like him, the ordeal and indignity would continue for months.

“I was always lying at work, so I could sneak out and withdraw my own money,” says Biswas.

“After work, I would go out looking for cash. I took my bike travelling to villages all the time looking for an ATM with cash. I would go to more than a dozen cash machines every day to look for cash.

“I bribed a guard to enter a dental college where I heard there was a less-used ATM. Even that had run out of cash.”

Modi had promised that the hardship would only last 50 days.

“Please, 50 days, just give me 50 days. After 30 December, I promise to show you the India that you have always wished for,” he said.

But 2017 arrived and the banks still didn’t have enough cash to give out.

It took months for things to return to normal.

A year later, analysts concluded Modi’s currency gamble had been an “epic failure”.

It had dealt a body blow to India’s informal economy, which ran mainly on cash. Small factories had shut, and poor workers had been laid off. One academic compared demonetisation in a booming economy to “shooting at the tyres of a racing car”.

One of Modi’s own economic advisers called demonetisation a “massive, draconian, monetary shock”. The US-based National Bureau of Economic Research found it had lowered economic growth by at least two percentage points in the last quarter of 2016.

January 2017: Congress politician Mamata Banerjee addresses a protest against demonetisation in Kolkata

By the central bank’s own admission, more than 99% of the “demonetised” money had been returned to the banks. Either there had not been much illicit money circulating in the system to begin with, or the owners had found ways to convert it into legal tender. Counterfeit currency accounted for a negligible amount of withdrawn notes.

Modi’s move to clean up the economy had yielded very little and made many suffer.

Many believed that state elections in Uttar Pradesh in March 2017 would be a judgement on demonetisation - and that the BJP would suffer.

They were wrong. The party won its biggest majority in nearly 40 years.

March 2017: Modi celebrates BJP victory in the state elections

Not everyone finds this surprising. A young student I speak to in Uttar Pradesh tells me: “In a divided and unequal society, the poor are willing to suffer if they are convinced that the rich are being hurt. It took them a long time to realise they were wrong.”

In other words, the currency ban was a moment of schadenfreude – feeling joy at another’s pain - for India’s masses.

But in Kolkata, Biswas finds it hard to forgive the prime minister.

“The humiliation I had to go through to access my own hard earned money was unbelievable,” he says.

“All this happened because we trusted Modi. We had believed him when he said this was to teach the corrupt rich a lesson. We believed that ordinary people had to sacrifice a little to help punish the dishonest.

“After that time, I don’t trust Modi any more. He has persistently lied to the people. This is not befitting of a prime minister.”

Rajasthan is an internationally feted tourist destination. It evokes images of gorgeous forts, colourful bazaars, art deco hotels and camel rides in stark deserts.

But the state is also a base of violent “cow vigilantism”, stoked by Hindu nationalist rhetoric.

Rajasthan is one of India's biggest tourist destinations

Many of India’s majority Hindus worship the cow as a sacred animal. Cow protection movements date back to the 1870s.

Conflicts over cow slaughter in the distant past have provoked deadly religious riots, protests outside the parliament, and even a hunger strike.

Cow vigilante groups have mushroomed since the BJP came to power in 2014.

To Modi’s supporters, the cow is totemic. Slaughter laws have been toughened and punishments made dire. In Rajasthan, cattle slaughter - or exporting cattle for slaughter - can attract a 10-year prison sentence.

In parts of north and west India, vigilante groups are a law unto themselves, setting up highway checkpoints, checking vehicles for cows, and roughing up dairy farmers, cattle traders and herders, mostly Muslims. Cow protection has become an extortion racket.

A cow vigilante group in Rajasthan, photographed in 2015

Human Rights Watch says at least 44 people – 36 of them Muslims – have been killed in vigilante incidents since 2015. Hundreds more have been injured.

Modi himself has condemned such attacks, and accused vigilante groups of being “anti-social” groups masquerading as cow protectors.

But BJP lawmakers close to the prime minister have sent out different signals. A cabinet colleague was photographed garlanding men who had been convicted for lynching a meat trader. A senior RSS official said the lynchings would stop if the Muslims stopped eating beef.

Pehlu Khan was killed for trying to take his cows home.

The 55-year-old dairy farmer lived in Nuh, a district of the northern state of Haryana with his wife and five children.

A nondescript place comprising a dusty town and a smattering of Muslim-majority villages and verdant farms, the people here till their land and sell cow milk for a living.

In April 2017, Pehlu was driving home in a hired pick-up with his two sons and two fellow villagers. They were transporting livestock they had bought at a cattle fair in neighbouring Rajasthan.

After driving a few hours and clearing some checkpoints, they realised they were being followed by six men on motorcycles, who overtook Pehlu and stopped the truck.

“We showed them the sale papers. They tore up the papers. They said they were from the Bajrang Dal (a radical Hindu right-wing group),” says Pehlu's son Arif.

Pehlul Khan's son Arif survived the attack

“Then they just dragged us down from the vehicle. They beat up my father most. They punched him, and beat him up with whatever they could lay their hands on - sticks, belts. Soon a mob gathered and joined the lynching.”

“They are Muslims. Just beat them up,” the mob howled.

By the time, the police arrived and rescued the men, Pehlu was already unconscious. The mob had snatched the cows, three phones and 45,000 rupees in cash.

The police took the victims to hospital. Pehlu died two days later. His sons survived the attack.

Villagers remember Pehlu as a devout, hardworking man.

“He worked hard to provide a decent life for all of us,” says his wife, Jaibuna.

Pehlu's widow, Jaibuna, and one of their sons

After his death, his family sold off their cows to pay for their legal expenses. The family did not receive any compensation.

“We barely survive now,” says Arif.

When it comes to cow lynchings, justice has been patchy in Modi’s India.

As he drifted in and out of consciousness before haemorrhaging to death, Pehlu Khan named six men as his attackers.

But before arresting them, the police filed a complaint against the victims, including Pehlu, for allegedly smuggling cows.

In September, the two brothers and two other witnesses to the attack were on their way to court to give evidence, when an unmarked SUV began following their vehicle.

“They drove up and shouted at us to turn back. When we refused, a man in the vehicle fired in the air. We turned our vehicle back and returned home,” says Arif.

I don’t hope for justice - I just want to live

Since then, he says, they have not responded to the court summons. The brothers say they will only do so if the case is moved out of Rajasthan.

“I am too scared. We lost our father. Now I don’t want to die. I don’t hope for justice. I just want to live,” he says.

Five months after the attack, charges against the six accused men were dropped by Rajasthan police. An independent report later accused state authorities of working to “diminish the enormity of the crime”.

Last December, the main opposition Congress party defeated the BJP and took power in Rajasthan.

“But nothing has changed,” says Arif. “The vigilantes still man the checkpoints. We are still scared to go out with our cows.”

In an apartment building tucked away in a warren of narrow lanes in the northern city of Lucknow, three young men have been studying up to 10 hours a day for months on end.

All they want is a job.

The young men are children of small farmers. They are first generation literate and part of an increasing number of Indians migrating to cities in search of jobs. All of them are from Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, with nearly as many people as Brazil.

Mithilesh Yadav, Karunesh Jaisawal and Ram Sagar Gupta

Armed with diplomas in engineering, the three men have sat exams for more than two-dozen jobs in the past year.

They head to exam halls on buses and second-class trains, sleeping in railway and bus stations to save money. They sit for gruelling exams, competing against tens of millions for a few thousand jobs. More than 20 million people applied last year for 63,000 jobs in the state-run railways, one of India’s largest employers.

Pune, February 2019: Candidates sleep out ahead of army job tests

The three men have been trying for jobs as train drivers, technicians, linesmen, engineers, clerks, government admin staff and even police officers. They have sat exams held by power stations, public works, and the railways. These are government jobs which offer dignity and security. But the competition is intense, and vacancies are few.

Hopes are dashed quickly.

The three men want to work as engineers, but are now reconciled to accepting whatever government job they can get. Job security is precarious. Karunesh Jaiswal, one of the three men, worked as a contract engineer for an aviation oil company last year and earned 17,000 rupees a month. Since his contract ended - and despite the experience - he hasn’t found another job.

“I don’t have a choice. I have to keep trying. When you are jobless in India, you are not alone,” says the 22-year-old.

Karunesh Jaiswal: “I don’t have a choice. I have to keep trying”

On the campaign trail five years ago, Narendra Modi fired the imagination of the young by promising plenty of jobs. But as he seeks a second term in office, India is in the throes of a massive unemployment crisis.

According to a leaked government report, the unemployment rate is at a 45-year-high.

More than 30 million people were looking for jobs in February, according to a study by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), an independent think tank.

A class at Dhyeya Coaching Institute in Lucknow, where students prepare for civil service examinations

Despite decades of brisk growth, vacancies have remained scarce.

India’s fastest growing industries – telecoms, banking, finance – do not offer enough jobs to absorb the country’s teeming army of poorly educated, low-skilled workers. Under Modi, private investment has slowed down and growth has sputtered, further hurting job creation.

More than 80% of India’s workforce are trapped in low paying, benefits-scarce “unorganised or informal” workplaces. Fewer than 10% of Indians actually work in the formal economy with full benefits.

Not surprisingly, getting a job is a Sisyphean struggle.

In their basic two-room, rented apartment, Jaiswal, Ram Sagar Gupta and Mithilesh Yadav wake up at five in the morning. After a quick breakfast, they sit on a bed and “self-study”. A map of India adorns the whitewashed walls. Books on engineering, maths, English grammar and general knowledge are strewn all over the place. Sometimes their parents call from the villages, and ask whether they have got a job yet.

Ram Sagar Gupta

“Those calls are the most difficult. I feel very sad to tell them the truth. But they always support me. The family keeps us going,” says Gupta.

He believes Modi will deliver the jobs one day. He still holds out hope.

“At least he talks about the dreams and aspirations of the young. He himself works hard. We still have lot of hopes from him.” His jobless flatmates are not so sure. “Where are the factories he promised to build?” asks one.

Mithilesh Yadav

Yadav says one of his uncles finally cracked a test for a policeman’s job after 10 years of trying. The uncle was 27 when he joined the force. “One day, I will also possibly get a job. But patience also takes a heavy toll,” says Yadav.

A plot of government land is the venue of Modi’s inaugural campaign meeting in the northern Indian city of Meerut.

Minutes after entering a flower-bedecked stage and acknowledging the lusty cheering from several thousand people in the audience, Modi launches into his speech with gusto.

“The 1.3 billion people of India have made up their mind,” he says.

“Once again India will have a Modi sarkar (government).”

Modi is a preternaturally confident politician. Although his powerful aide Amit Shah has stitched up some smart alliances, he has made 2019 a verdict on his performance.

He is a tireless campaigner. In 2014, according to the BJP, he travelled more than 300,000km (186,000 miles) across 25 states to “connect to people”. This year, according to the BJP, he has travelled the entire country over 51 days and addressed 142 public meetings - a third of those in the two crucial states of Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal.

Modi is also pugnacious, deftly mixing nationalism, dog-whistle politics and populism.

He’s adept at creating binaries: the nationalists (his supporters) versus the anti-nationals (his political rivals and critics); the watchman (Modi himself, protecting the country on “land, air, and outer space”) versus the entitled and the corrupt (an obvious dig at the main opposition Congress party). Sometimes his campaign has sounded like he’s blaming previous governments for all ills - rather than a vision for the present.

2019 has been a bruising and brutal campaign.

India’s Grand Old Party, the Congress, led by a resurgent Rahul Gandhi, has unsuccessfully tried to re-establish itself as a credible opposition after sinking to its lowest tally in 2014. The BJP has also fought off the threat from a host of regional parties which are powerful in a number of states.

Arvind Panagariya, a professor of economics at Columbia University who served as the vice-chairman of a government think tank under Modi, has always believed that the prime minister would win a second term, despite what critics said.

He says Modi remains intensely popular with people and has “enormous energy and ability to communicate with the masses”.

“He has successfully conveyed to the average Indian that he is sincere, hard-working and decisive.”

Some analysts believe India is headed for a second “dominant party system”, this time led by the BJP. Previously, Congress led the country for more than four decades.

But one thing is clear - 2019 has proved that the power of Modi endures for now.