He is staring at me. I feel it.

His pale blue eyes are cold and penetrating.

But it is his expressionless face that is most unnerving - a face disfigured by bayonets. Daylight seeps through holes that have been gouged into his cheeks and forehead.

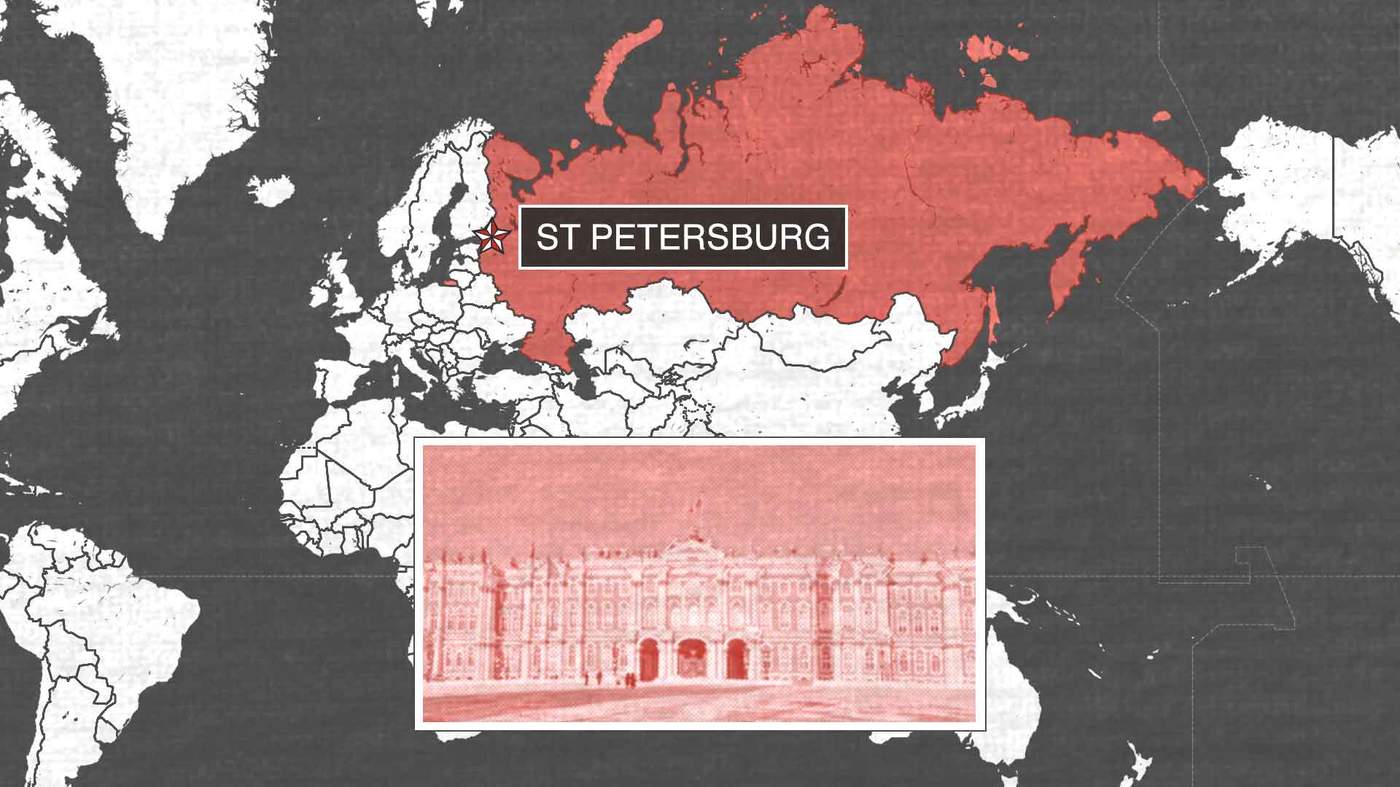

This portrait of the Russian Emperor Alexander II transfixes me. The Austrian artist Heinrich von Angeli painted it in 1876. Russian revolutionaries ran their bayonets through it in 1917 when they seized the Winter Palace in Petrograd - as St Petersburg was then known - a sign of their hatred for the old Russia they were sweeping away.

Ever since, the painting has been hidden in the vaults of the State Hermitage Museum housed in the Winter Palace. For the 100th anniversary of the revolution, the damaged portrait is being displayed in Russia for the first time. I am given a private viewing.

It is only a painting - just oil and canvas. But the pockmarked face of Emperor Alexander conveys the drama and the brutality of Russia’s revolution more powerfully than anything I have seen.

There were, in fact, two revolutions in 1917.

The February Revolution deposed the monarchy. The imperial Winter Palace became the seat of the Provisional Government.

The second revolution imposed Bolshevism on Russia, creating the world’s first communist state.

The Great October Socialist Revolution – as it became known – actually took place on 7 November. But in 1917 Russia was using a different calendar from the West, according to which the date was 25 October.

Soviet propaganda would portray what happened as a mass uprising of workers, peasants and soldiers who – led by the Bolsheviks – stormed the Winter Palace to seize power for the people.

That was the picture dutifully painted by Soviet cinema. A decade later, film-maker Sergei Eisenstein re-enacted the revolution for his epic entitled October.

Filmed on location at the Winter Palace, it depicted Red October as Russia’s Bastille moment, with thousands of people breaking down the gates of the palace and pouring inside. The cruiser Aurora was accorded a starring role - firing the shot that signalled the start of the uprising.

The Aurora

It was a magnificent spectacle. But it wasn’t true. The Winter Palace is widely believed to have suffered more damage from Eisenstein’s film crew than from the actual revolution.

In 1917 there was no dramatic storming of the Winter Palace. Most of the Red Guard revolutionaries who had got inside did so through an unlocked door.

As for claims of a mass uprising, this was fake news from the Bolsheviks. Red October was a coup. Vladimir Lenin’s party had seized power in Russia.

In St Petersburg a century on there are few banners or advertising hoardings celebrating the anniversary of Red October, and there are no official commemorations on the scale, or style, of a French Bastille Day. For if modern France still identifies with the ideals of its revolution – “liberty, equality, fraternity” - modern Russia, particularly its government, is hesitant about 1917.

Like Russia’s national symbol - the double-headed eagle - the Russian authorities are torn two ways over the events of 1917. On the one hand, Red October gave birth to the Soviet Union, a superpower President Putin has often praised. The Kremlin leader once described the collapse of the USSR as “the greatest geo-political catastrophe” of the 20th Century.

Yet an armed uprising against the government is not the kind of example the Kremlin wishes to promote - especially in the light of Russia’s economic problems.

“The attitude of the authorities to the Russian Revolution is radio silence,” says historian Sergei Podbolotov. “One of the revolution’s main ideas – the abolition of private property - is totally alien to the current regime. So is the idea of taking up arms and attacking police.”

But the revolutionary cocktail of a century ago - food shortages, an unpopular war and widespread disillusionment with the government – does not exist today.

Despite Western sanctions against Russia, the supermarket shelves of St Petersburg are well-stocked. The coffee shops and trendy bars of Nevsky Prospekt are packed with young Russians chatting on smartphones or glued to their tablets.

Many of these people were born after 1991, the year communism collapsed and the Soviet Union crumbled.

Nevsky Prospekt

Bathed in the sunlight of a late Russian autumn, the “Venice of the North” looks like an oasis of calm. But political discontent still stirs.

In a St Petersburg park, named after Mars, the Roman god of war, hundreds of people have gathered for an anti-government protest. Many are supporters of opposition leader and Kremlin critic Alexei Navalny, who wants to run for president next March. But convictions for fraud, which Navalny claims are politically motivated, bar him from the ballot. The suspicion that the Kremlin is not playing fair has brought people out on the streets.

“I want to live in a Russia that is fair to all its citizens,” one of the protesters, Olga, tells me. “And I want a leader who listens to his people. Vladimir Putin doesn’t.”

“Personally, I don’t think that Navalny would be a good president,” another protester tells me. “But I believe elections should be democratic – not what we have now.”

No-one here is calling for a 21st Century Russian revolution.

“Revolution means blood and deaths,” Katya tells me. “We want honest elections, not revolution.”

The authorities are taking no chances. There is a heavy police presence. Through loudhailers, police are asking the crowd to disperse, declaring this an unsanctioned gathering. The protesters believe they do not require permission to express an opinion.

Some of the protesters decide to march off through the city centre. It is Vladimir Putin’s birthday. The crowd is about to spoil the president’s party.

“Putin is a thief!” they chant.

“Russia without Putin!”

“Send the tsar to the labour camp!”

Riot police with truncheons line up across the road. Minutes later, they start dragging people from the crowd. Police buses quickly fill up with detained protesters.

At night a few dozen protesters appear outside the Winter Palace. They hold up signs with Alexei Navalny’s name and chant sarcastically “Happy birthday!” to the president.

Their protest is a faint echo of those 1917 revolutionaries who seized the palace and dug holes in Emperor Alexander’s portrait.

Yet these young people are not here to make a revolution. They are making a point - that the government should listen to the people.

The Russian authorities often brush off protesters as a tiny minority. But with real incomes falling and 20 million Russians living below the poverty line, any signs of dissent make the Kremlin nervous.

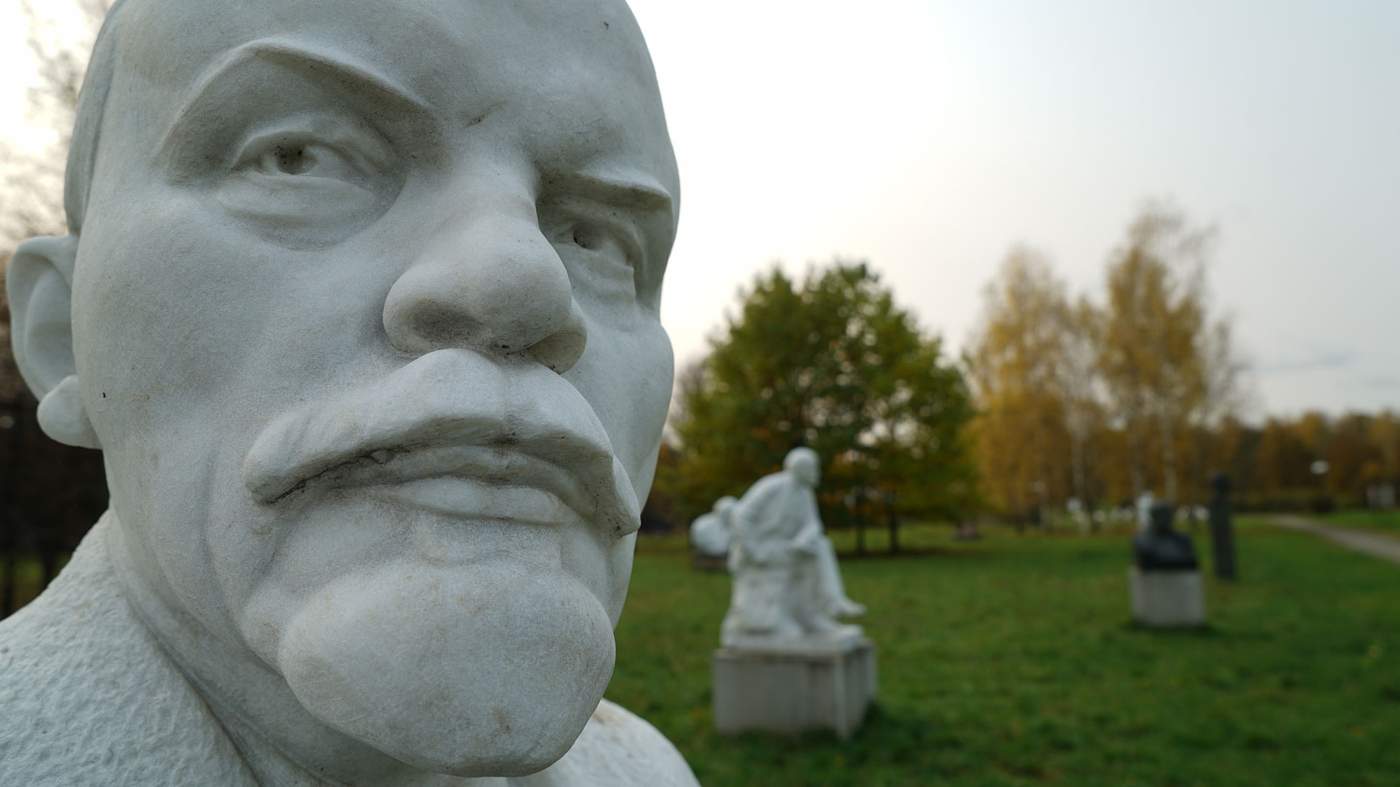

I see the ghosts of communism past.

Philosopher Karl Marx is here. He looks deep in thought.

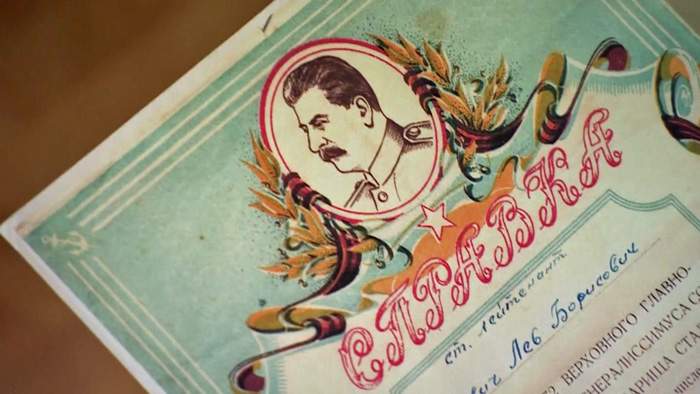

Dictator Joseph Stalin is here, too. He looks sinister.

Once communist idols, these giants of history – or rather their statues – have been put out to grass in a park near Moscow.

Here, too, stands the leader of the Russian Revolution, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known to the world as Lenin. Indeed, there are lots of Lenins here. In one pose, he is the great thinker, with hand on chin. In another, he’s chatting to children. A third statue has Lenin toiling away at his desk.

A recent study calculated that there are more than 14,000 Lenin statues across the former Soviet Union. It used to be that wherever you went in the USSR, you could be certain there was at least one Lenin looking your way.

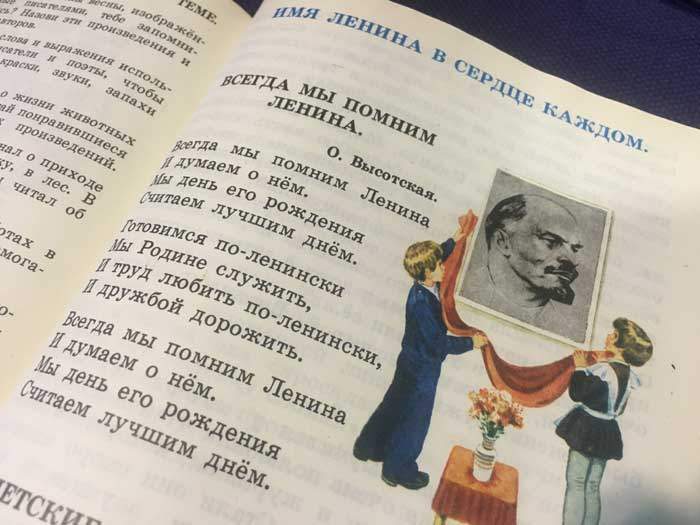

In life, Lenin was a charismatic revolutionary. In death he was transformed into communism’s first personality cult. As well as the statues, his face stared down on Soviet citizens from billboards; his portrait was carried at communist parades; he was praised in songs and poems. The cradle of the Russian Revolution, St Petersburg, was renamed Leningrad in his honour.

Lenin taught generations of Soviet children to read. On a trip to the USSR, I once bought a reading book for nine-year-old school kids to practise my Russian. Here is my translation of page 149:

“Lenin’s name is in everyone’s heart!

“We always remember Lenin,

We think of him so dear.

We consider that his birthday,

Is the best day of the year.

“We learn to serve the motherland,

Just like Lenin would,

To love labour and value friendship,

Like only Lenin could.”

Accompanying the poem is a picture of two children gazing religiously at Lenin’s portrait.

It is one of the ironies of the Russian Revolution that the man who led it, who waged war on the Church and declared all religious ideas “an abomination” ended up the closest thing communism had to a god.

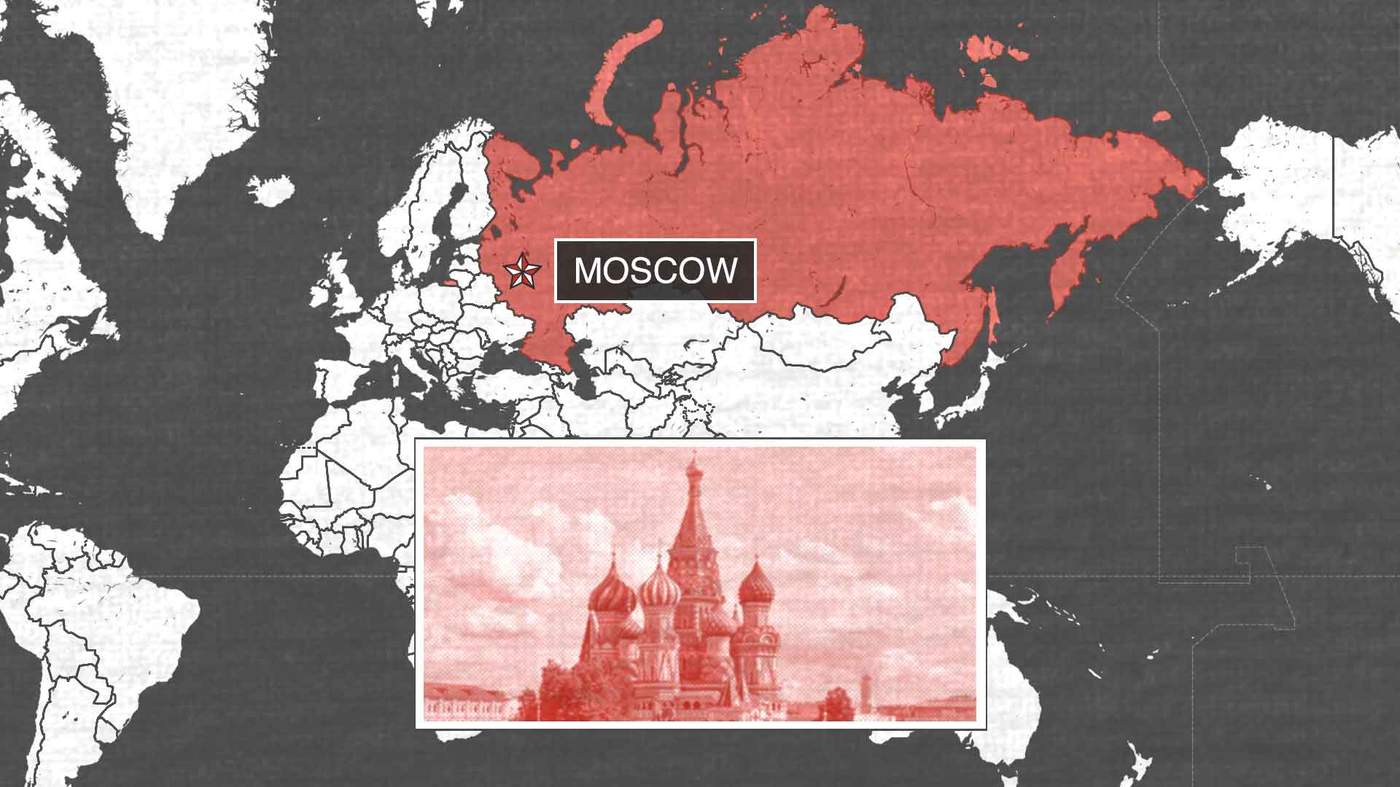

At the heart of this cult was Lenin’s final resting place - the macabre mausoleum on Red Square, where his embalmed body was displayed and worshipped like a Soviet saint. A whole scientific institute was created to preserve the corpse. To keep Lenin looking like Lenin, the team of scientists has had to replace some skin and flesh over the years with plastics and other materials.

In communist times people would queue for up to six hours to see the body of the "vozhd", or "great leader". Not today. To many in modern Russia, Lenin is more a museum piece than an object of adoration. Curiosity still draws foreign tourists. But the much shorter queues suggest that Russians have lost interest in him.

1950: The queue to see Lenin's body stretches across Red Square

Today there is a new cult in town. True, I have yet to see a statue of Vladimir Putin in Moscow. But the souvenir shops here are full of Putin busts. You can also buy Putin mugs, fridge magnets, T-shirts, smartphone covers, even Putin chocolates. You name it, Putin’s face is currently on it. I have counted at least five different Putin 2018 calendars on sale in the newspaper kiosks. They all feature various pin-up poses of Russia’s action-man president.

While Brand Putin sells, Bolshevik Lenin is under fire. And it is the Orthodox Church, increasingly influential in Russia, which is leading the charge against him.

“One lesson of the revolution is we should not allow society to be shaken by people coming from abroad with a special task,” Metropolitan Hilarion, head of external relations for the Russian Orthodox Church, tells me.

Metropolitan Hilarion of the Russian Orthodox Church: The Bolshevik revolution was a “criminal” act

“The Bolshevik revolution started with the arrival of Lenin and more than 200 other revolutionaries who came by train through Germany. Their trip was sponsored by Germany, which was at war with Russia. This indicates the whole affair was criminal.”

In other words, with Lenin’s help, a foreign power orchestrated regime change in Russia in 1917. The argument has a contemporary ring to it. In recent years Moscow has accused Western governments of plotting social unrest in Russia.

The Russian authorities also link the West to the so-called “coloured revolutions” that have deposed pro-Moscow regimes, from Ukraine to Georgia. Russian officials often refer to Red October as “the first coloured revolution.”

So, if Vladimir Lenin is a fallen idol, is it time to remove him from the mausoleum and bury his body?

Despite Lenin’s declining popularity, it is a controversial question. When debating it earlier this year, a popular Russian TV talk show descended into a shouting match.

“Remove Lenin, he’s a criminal,” shouted one nationalist politician.

What’s the point?” retorted a communist MP. “Will that make food prices any lower?”

A nun chimed in: “Who brought us Lenin? The Germans did in a sealed train. I say put his body back in the same train and send it back to them!”

Among the guests taking part in that raucous TV show was businessman Stanislav Svistunov. I visit him at his factory in the north of Moscow.

Stanislav’s company decorates plastic products, including funeral accessories. Plastic coffin handles and crucifixes go into the machines and when they emerge they are sparkling with a golden coating.

There is an irony to Stanislav being in the business of religious appendages.

He shows me a book. It is the family history of Vladimir Lenin - the communist who declared war on the Church.

“I am Lenin’s great-great-grandnephew,” declares Stanislav, pointing to a family tree. “My great-great-great-grandmother, Sophia, was the sister of Maria, Lenin’s mother.”

Stanislav assures me that only once did his family benefit from their famous relative. One year back in the 1930s winter was so cold that his great-grandfather and great-grandmother had to burn some of their furniture to keep warm. Out of desperation they wrote to the authorities mentioning the family connection.

Stanislav Svistunov - related to Lenin

“Some people came to check their identity papers. Shortly after, a lorry arrived with firewood. My great-grandfather was sworn to secrecy about it.”

As for what to do with Lenin’s body, Stanislav assumes it will be up to the Kremlin to decide.

“Only one man can take the decision to bury Lenin - our president,” Stanislav tells me.

He raises an interesting point. If Lenin’s body is removed from Red Square, does that mean all the other bodies interred there should be taken away, too?

There are lots of them. More than 200 revolutionaries lie in a mass grave on Red Square. Also buried beside the Kremlin are dozens of Soviet leaders, scientists, military commanders and cosmonauts.

“One idea may be to bury Lenin inside the mausoleum,” suggests Stanislav. “This would partly satisfy those people who say his body should be in the ground, and those who want him to stay on Red Square. I back this option.”

The Orthodox Church takes a different view.

“He should be buried. Not because he deserves a Christian funeral - he was anti-Christian. But because this symbol of the revolution should find its proper place - not on Red Square and not in a mausoleum,” says Metropolitan Hilarion.

“I regret his burial was not conducted in the early 1990s, when it would have been easier to do. It is more difficult now. There will be protests. The Communist Party is strongly against this. But I believe it is only a matter of time before he is buried. This should be done sooner or later.”

“Lenin lived! Lenin lives! Lenin will live!” proclaimed a famous Soviet slogan.

In a way, he does live on - in the thousands of Lenin statues, Lenin Avenues and Lenin Squares that exist in Russia to this day; in his mausoleum beside the Kremlin; in the hearts of committed communists. But the shadow he casts over Russia is fading. Whether or not his body remains in Red Square, to most Russians now the man who made the revolution is like those statues I saw in the park - a ghost from a lost world.

Outside Yekaterinburg, autumn has carpeted the forest with golden leaves. All around me, silver birches seem to be whispering, as their leaves rustle in the breeze.

It is so beautiful here - like walking through a Russian fairy tale.

Then, through the trees, I spot something that jars with the magical setting - an Orthodox cross. It marks the place of a grim discovery - the remains of Russia’s last tsar, Nicholas II, and his family. The Bolsheviks had murdered them, mutilated their bodies, and disposed of their victims in a shallow grave in the forest.

Pensioner Vladimir Kotlyakov is sweeping leaves and twigs away from the cross. He comes every day to keep this place tidy.

The Soviets demolished the Ipatiev House in 1977 - an attempt to erase the memory of the tsar. But on the spot where the house stood, modern Russia has built a church.

The tsar’s killers saw themselves as gods. This sickness of the mind became the fever of the 20th Century.”

Painted on the walls of the Church on the Blood are scenes from Tsar Nicholas’s life, such as his coronation. At the front of the church an icon bears the faces of the tsar, tsarina and their children. The Orthodox Church has elevated them to sainthood.

“The calamities Russia endured, the civil war, the 1930s terror, World War Two, they were all a punishment for what happened here,” Bishop Yevgeny of the Urals diocese tells me.

“Emperor Nicholas understood that God was above him. But the tsar’s killers saw themselves as gods. This sickness of the mind became the fever of the 20th Century.”

In the 1990s, a Russian government commission concluded that the bones exhumed in the forest belonged to Nicholas, Alexandra and three of their children - Olga, Tatiana and Anastasia. They were laid to rest in St Petersburg.

In 2007 what were believed to be the remains of Maria and Alexei were found. The Russian Orthodox Church demanded further tests and has yet to recognise these as the remains of the Romanovs. But when I spoke to him in Moscow, Metropolitan Hilarion indicated that there was “a very strong chance” the Church would do so in the near future.

In a building next to the Church on the Blood, I attend a children’s choir rehearsal. Looking down from the wall is Nicholas II. His portrait provides inspiration to the young choristers.

“The tsar and his family set us a moral example that we try to follow,” Alexandra explains. “They believed in God so much, they suffered for it.”

“I always think of him as the captain of a big ship called Russia,” says Anastasiya. “He was on this ship till the very end, till the country ended. He was so brave and I admire him.”

![Anastasiya: “[Tsar Nicholas] was so brave and I admire him.” Anastasiya: “[Tsar Nicholas] was so brave and I admire him.”](https://news.files.bbci.co.uk/include/shorthand/38658/media/nastya700-lr_mqmxmpr.jpg)

Anastasiya: “[Tsar Nicholas] was so brave and I admire him.”

It is an idealised and somewhat distorted image of Russia’s last tsar. For, if Nicholas II was the captain, does he not bear some responsibility for the sinking of imperial Russia?

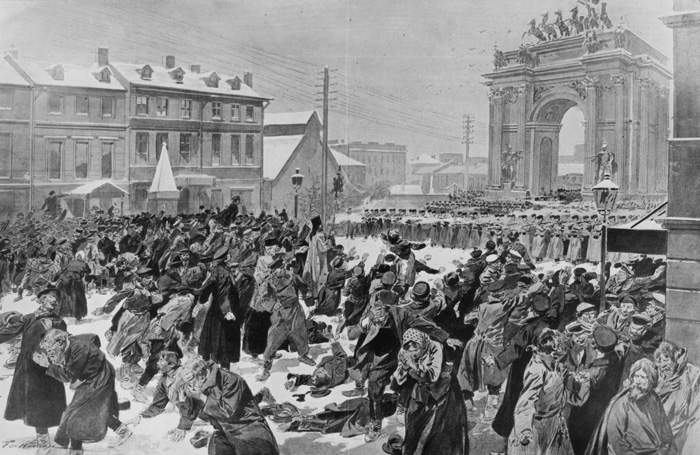

It was the tsar’s soldiers who fired on peaceful protesters outside the Winter Palace in 1905. It was Nicholas who brought the mystic and faith-healer Grigory Rasputin into the royal court. As a private adviser to the Romanovs, the renegade monk interfered in matters of state and further damaged the prestige of the monarchy.

Illustration portraying Bloody Sunday, January 1905, when tsarist soldiers fired upon unarmed marchers in St Petersburg

Nicholas’s decision to take personal command of the tsarist army in World War One proved disastrous. And ever the inflexible autocrat, the tsar was incapable of steering Russia clear of revolution.

The Provisional Government that took over from him made mistakes, too. But ultimately, the Bolsheviks seized power in a country that had been weakened by years of imperial mismanagement.

In post-communist Russia, it is not only the tsar who is enjoying a revival. So is the Church. In 1989, Russia had 6,000 Orthodox churches. Today there are more than 36,000.

Formerly a pillar of tsarist autocracy, Orthodoxy once again enjoys a close connection to the state. As the Kremlin strives to shape a new national ideology around patriotism and ultra-conservative values, the Church is playing a key role.

In a school playground on the edge of Yekaterinburg, I watch children practising traditional Cossack sword-spinning. The school, which has built its own church, is one of several in the area where education is centred on piety, patriotism and a glorious past.

“We are rediscovering our culture of a century ago, not just with swords, but with songs and dances,” 14-year-old Nikolai tells me. “But for me, faith is the most important thing in life - it is the reason we are here.”

I talk to the school director, Alexei Solovyov. He recalls that in Soviet times, when atheism was an official state doctrine, only one church was open in Yekaterinburg, or Sverdlovsk, as it was known under communism. It is a city of more than a million people.

“Outside the church there were always police in civilian clothes,” recalls Alexei. “They didn’t harass the old people. But any young people that went up to the door were taken aside for a conversation.”

Yet communism failed to replace God in Russians’ hearts.

“My great-grandmother was a communist,” Alexei recalls. “She worked as a cook. She even cooked for Tsar Nikolai’s killers in the Ipatiev House. But in the 1930s she was a victim of Stalin’s purges. She spent five years in the gulag for being a ‘Trotskyite’. When she came out, she ditched all that revolutionary hype and turned to religion.”

But if Russians are looking to the past to shape their future, might they decide to restore the monarchy? That is unlikely.

“Monarchy is a good way of governing,” schoolteacher Olga tells me. “But times have changed. Anyway, our president is a man who kind of governs the way the tsar tried to govern. He is a real ruler, a real patriot. He doesn’t allow other countries to humiliate our citizens.”

Back in the forest, where the bones of Nicholas II were found, Vladimir Kotlyakov seems confused.

“Russia needs a tsar. I’m fed up with disorder here. ‘President’ isn’t a Russian word. ‘Tsar’ – now that’s a Russian word! Let the people choose a tsar.”

My trip to Yekaterinburg has reminded me that Russia is a country of extremes.

It is a country that can leap from “Down with the Tsar!” to “Saint Nicholas”; from destroying churches to building them; from communism to capitalism; from freezing winters to boiling hot summers.

It is a country of contradictions.

The Russian Revolution hadn’t even happened when Lev Lipovich was born.

By the time the Bolsheviks had seized the Winter Palace, Lev was already seven months old.

A hundred years of Russian history are etched into his face.

Lev Lipovich

“I fought in four wars, and I survived three famines,” Lev tells me with a hint of pride.

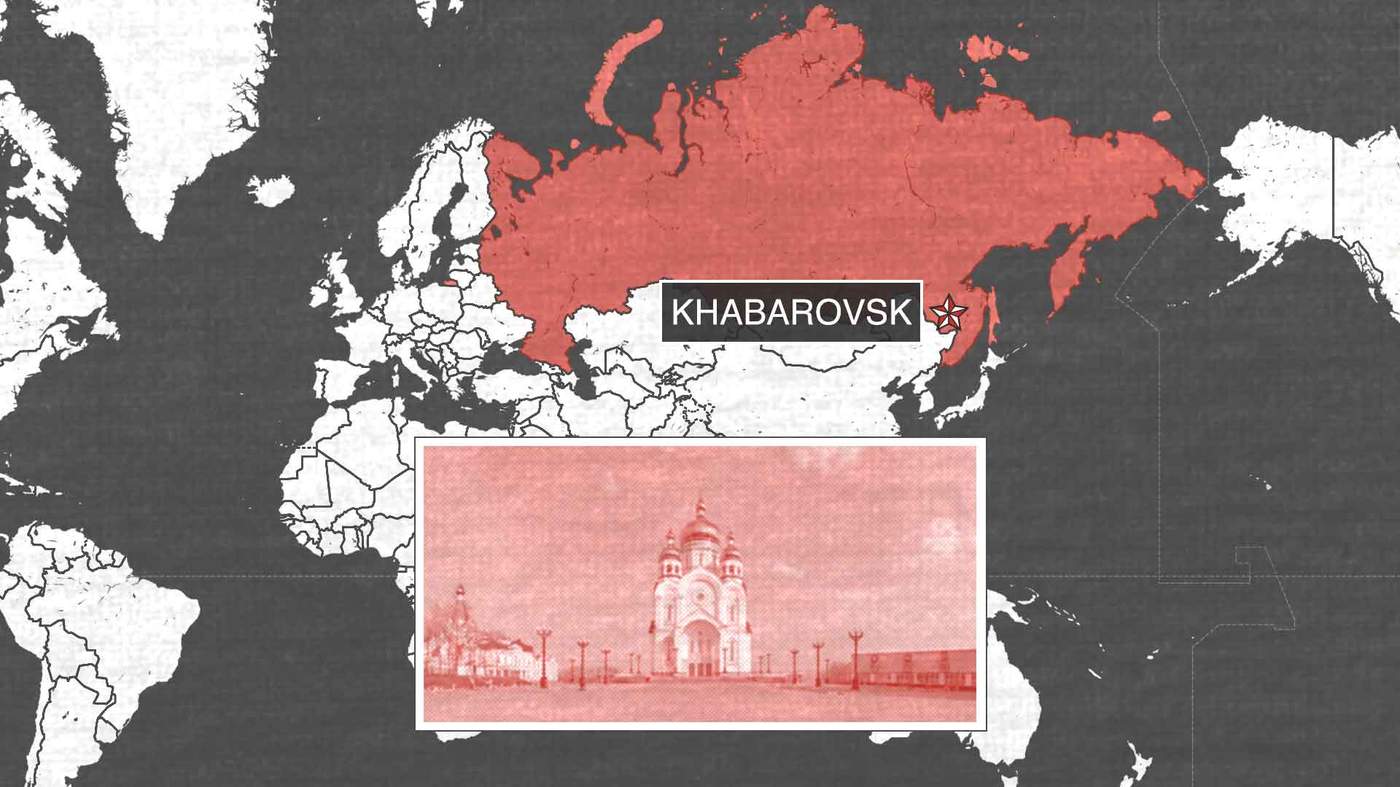

We are sitting in his tiny apartment in the city of Khabarovsk, the capital of the Russian Far East. Out of the window you can see the point where the two great rivers of eastern Russia meet - the Amur and the Ussuri.

On the roads here there are few Russian-built cars - it is cheaper for people to buy right-hand drives from Japan. The border with China is just 25km from here.

Red Square feels a world away. And we are more than 6,000km (3,700 miles) from the cradle of the October Revolution, St Petersburg.

Khabarovsk

“I am a son of October,” he explains. “To me, Revolution Day - 7 November - is my second birthday because I see that as the day the USSR was born.”

Lev was born in the Crimea in April 1917. When he was 11, his parents sent him to a factory boarding school.

“For my first 20 years my motherland fed me, clothed me, put shoes on my feet. It gave me an education. When I joined the army, I started to repay my debt to my country.”

At the age of 15, Lev learnt to fly. He became a fighter pilot. His first experience of battle was the Winter War between the Soviet Union and Finland; he fought in World War Two, what Russians refer to as the Great Patriotic War; in 1945 he flew missions against Japan and in North Korea.

The decisive battle of the civil war took place near Khabarovsk, on a hill by the village of Volochaevka. When the Reds won, the victors did all they could to make sure that history would record them as the heroes.

Soviet artists produced a 43m-long panoramic painting of the battle to proclaim the victory of communism. It was celebrated in song, too. A military march about Volochaevka became one of the most popular numbers in the Red Army Choir’s repertoire.

On the battle site, a museum was built to honour the heroism and sacrifice of the pro-Soviet soldiers. A memorial plaque referred to 118 Reds in a communal grave. There was no mention of the Whites who died here.

The monument marking the battle at Volochaevka

Yet as post-communist Russia begins to look more critically at the revolution, the official interpretation of the civil war, too, is changing.

On Volochaevka hill today the museum is closed; the building is crumbling. The Orthodox Church has erected a small chapel here - a sign that this area is no longer a communist shrine.

At the local high school, children are taught that the civil war was a tragedy for all Russians, with no “good guys” or “bad guys”. The school museum recounts the battle of Volochaevka in neutral tones. On display here are rusting bayonets, bullet casings and guns from the battle, found by students in the forest.

“It would be wrong to show a bias for the Reds or the Whites,” teacher Alexei Zaitsev tells me. “We try to find a middle way and recount this historical event through facts.”

The school museum is open to the public. But not all the visitors appreciate the revised history.

“It wasn’t that long ago that the Soviet Union disappeared,” Alexei reminds me. “Some of our visitors still support the USSR and don’t like what we say now about the Whites.”

Like shifting sands, the past in Russia seems to change right under your feet. One moment Russians are being told to praise “Great October”; the next they are being told the revolution was not so great after all. One day religion is the “opium of the people”; the next it is the life and soul of Russia. So often here the past is rewritten, reinterpreted, reshaped, depending on who is in power.

“Every 50 years everything changes here. We cope.”

Back in Khabarovsk, I meet three generations of one family strolling in the park: 13-year-old Sofia, her mother, Anna, and grandmother, Nina.

“It’s difficult when history changes,” Anna tells me. “It’s hard for youngsters to understand what is good and what is bad. TV says one thing, parents say another and teachers say something else.”

“Yes,” says Sofia. “It’s hard to know which opinion is the right one.”

“Then again, it’s always been like this in Russia,” reflects Anna. “Every 50 years everything changes here. We cope.”

On the banks of the Amur river, I chat to pensioner Alexander Vasilievich. He is clearly struggling to make sense of Russia’s past.

Alexander accuses the man who led the October Revolution of hoodwinking the people.

“Lenin promised land to the peasants and factories to the workers. But he didn’t deliver.”

He remembers how empty the shops were in Khabarovsk in Soviet times.

“I used to fly to Moscow to buy shoes,” he admits. And yet Alexander is nostalgic about the communist past.

“I want it all back as it was. Back then I always had a job and a decent salary. Workers had more social protection, too, than now.”

“Not under Stalin, surely?” I reply. “What about the terror?”

“Who on earth knows who was right back then and who was wrong?” he answers.

“Who on earth knows…?” is not the kind of question you will hear from 100-year-old Lev Lipovich. I suspect he will always see himself as a “son of October” and retain an iron belief in the revolution and its ideals.

But on my journey across Russia I have met many people who feel confused and disoriented by the current reinterpretation of history. For life is not easy in a country where not only the future is unpredictable, but also the past.