“Ehe... ehehehehehe... eh-he-he-hee... ahahahahayeee.”

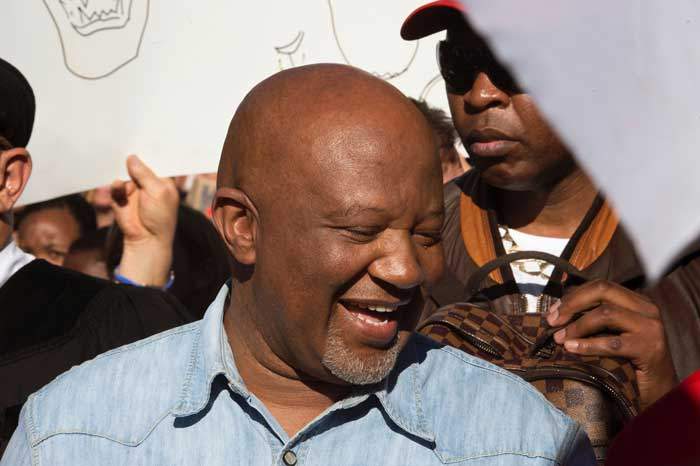

The warm, rich, indulgent chuckle of South Africa’s President Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma ripples through a solemn conference chamber in Pretoria.

It’s his trademark - a disarming, seemingly unlimited well of good humour, deployed to break the ice, lighten the mood and wrong-foot his opponents.

Many people who know him talk of Zuma’s extravagant charm.

I remember watching him gleefully bounding on to a stage, one cold night in central Johannesburg in April 2009, to celebrate the election victory that had just elevated him to the post once occupied by President Nelson Mandela. His laughter, his dance moves, his raucous singing - all seemed to promise a new era of confidence and energy for a country finally being led by “one of us” - a charismatic, salt-of-the-earth man rather than his predecessor, the elitist “professor” Thabo Mbeki.

Flawed, yes, the cheering crowds might have conceded. But aren’t we all?

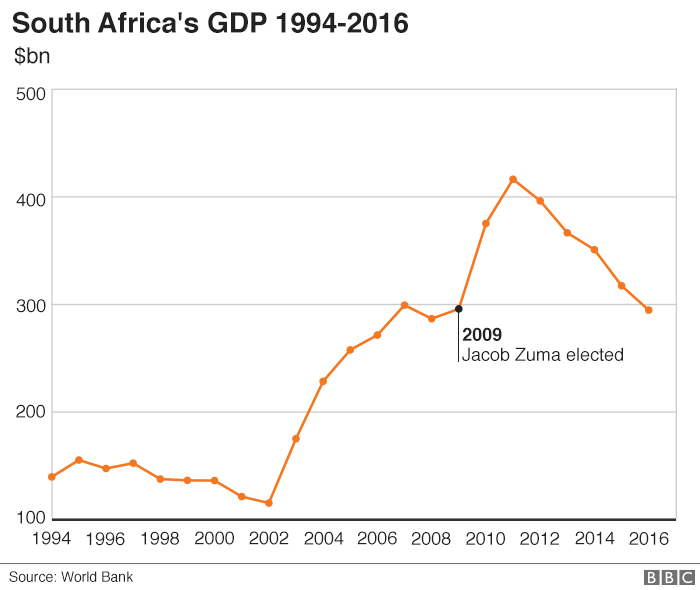

Today, after nearly a decade as South Africa’s leader, Jacob Zuma’s laughter has turned against him. To many in this country it has become a jarring, charmless cliche - the hollow mirth of a man whose presidency is widely blamed for the corruption, misrule and economic stagnation that now afflict a nation.

“President Zuma represents a betrayal of the South African dream,” says Sipho Pitanya, a leading critic from within the ANC, the liberation movement that came to power a generation ago after the long struggle against racial apartheid.

“Zuma lives up to his middle name. It’s a Zulu name that means, ‘I laugh at you as I destroy you.’ He is brazen and reckless,” says Redi Tlhabi, author of a book about the woman who accused Zuma of rape.

And yet others argue that Zuma is a victim of outrageous prejudice, mocked for his lack of education and his rural upbringing - his genuine achievements in government overlooked by a biased “white media” in favour of a relentless focus on his personal failings.

Zuma doesn’t have to do anything for him to be disliked. The prejudice is so ingrained”

“The accusations against Zuma are clouded by suspicion, by prejudice, by conjecture... spun by a very aggressive media,” says Jessie Duarte, deputy secretary-general of the ANC and a former special assistant to Nelson Mandela.

“You have a peasant, with no university degree... Zuma doesn’t have to do anything for him to be disliked. The prejudice is so ingrained,” says the political commentator Prof Sipho Seepe, who has in the past advised the Zuma administration.

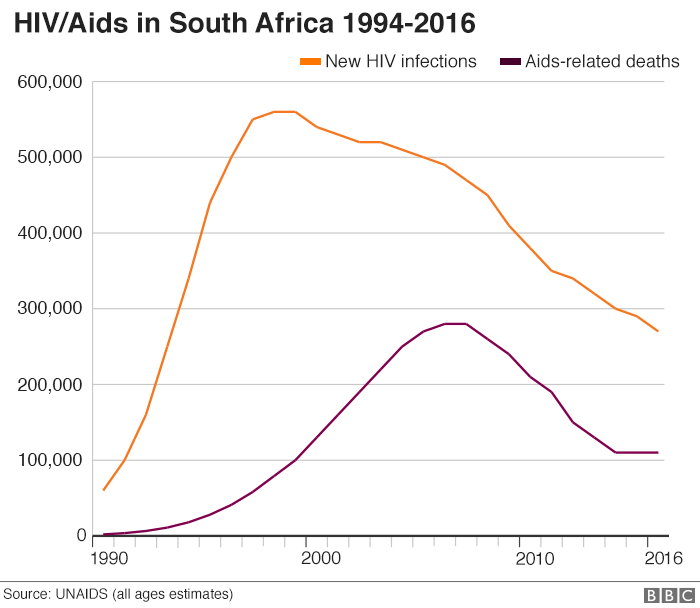

His supporters point to the successful fight against HIV/Aids and his efforts to push the government to focus more on tackling rural poverty. Under Zuma, higher education has become a priority, the civil service has expanded dramatically (for better and worse), ministries are more closely monitored, in theory at least, and a long-term National Development Plan has won support from across almost the entire political spectrum.

But which is the real Jacob Zuma?

Much of his life story is one of hardship overcome. He grew up as South Africa’s economy and society were being warped by the racist policies of a white-minority government that sought to separate, suppress and control the black majority.

Zuma’s father was a rural policeman who died when his son was five. His mother struggled to earn a living as a domestic worker in Durban, unable to give her son a formal education. As a teenager, Jacob joined the ANC, and then its underground military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe - formed to fight against the apartheid government both from within South Africa and from bases in neighbouring countries.

He was considered a “bright, very keen” recruit - uneducated but with an obvious intelligence and leadership potential.

In 1963, he was arrested by the apartheid police and sentenced to 10 years in prison on Robben Island along with Nelson Mandela and other prominent leaders in the liberation struggle. After his release he quickly resumed work in the ANC’s underground intelligence structures, mostly in exile in countries like Swaziland and Mozambique.

“A very charming person, very grounded, a man of the people, charismatic. Not as sophisticated as Thabo Mbeki, but very strategic,” remembers Colin Coleman, who met him in exile and now runs Goldman Sachs in South Africa.

But others were more wary.

Ronnie Kasrils was initially won over by that “very engaging laugh... we got on famously”. But as the two worked closely together for the ANC in Mozambique, he came to see a different side.

“Behind the facade of this simple man, he’s highly ambitious... very spiteful and even vindictive,” Kasrils - who would later become minister of intelligence in democratic South Africa - remembers thinking.

But the ANC was engaged in a deadly struggle against apartheid. Flaws and mistakes had to be overlooked until the fight was over. Finally, in 1990, Jacob Zuma returned home to take up increasingly powerful positions in a South Africa that was shedding its apartheid past and transforming into the so-called “rainbow nation”.

For Kasrils, Zuma’s true nature was now on show. “Power really reveals your character.”

In an elegant, wood-panelled courtroom in Bloemfontein, on the high plains of central South Africa, earnest, gowned lawyers are arguing, respectfully, about a case that has mesmerised and frustrated this country for years.

It is September 2017, and the matter before the Supreme Court of Appeal is the fate of allegations of corruption, fraud, racketeering, money-laundering and tax evasion. In all there are 18 charges relating to 783 payments.

Their origins stretch back to the early 1990s when the newly democratic country was overhauling its military, and a 30bn rand ($5bn; £3bn in 1999) arms deal involving a number of European companies led to allegations of bribery. Zuma has always denied any wrongdoing.

The charges have been challenged, dropped, changed, challenged again and reinstated over so many years, by so many different lawyers, judges and prosecutors, that they now carry about them a cobwebbed, Dickensian, aura of legend. The charges that will not die. The “zombie” case.

The accused is Jacob Zuma. And the allegations against him have overshadowed his entire presidency.

Zuma has never been good with money.

Zuma was a good guy, warm guy, but, man, I don’t know what happened to him”

In the early 1990s the political exiles rushed home not just to take up leadership positions but also to rebuild their shattered family lives and make up for so many lost years.

Jacob Zuma in the 1990s

Many were broke, some were profligate, and a few were inclined to believe that, having sacrificed so much for their country’s freedom and its peaceful transition to democracy, they were now entitled to something more.

“Zuma was a good guy, warm guy, but, man, I don’t know what happened to him. Pure greed, for himself and his family,” says Bantu Holomisa, a former member of Nelson Mandela’s government but now an opposition MP.

In Durban, Zuma quickly found himself targeted by businessmen eager to build contacts with those who seemed destined for high office in the new ANC government.

“I don’t believe Jacob Zuma was a bad person, but he became surrounded by these people, and that's where the rot can effectively set in,” says Goldman Sachs’s Colin Coleman.

This is a man who now feels the country owes him a livelihood

Soon, Zuma was rising fast in the government of his home province, KwaZulu-Natal. He had a state salary, but before long, it is widely alleged, he was running up debts for groceries, cars, school fees and for the home he was building in his village of Nkandla.

“Zuma had such a huge appetite. He comes back with numerous children and at least two wives. This is a man who now feels the country owes him a livelihood,” says Kasrils.

Zuma has been accused of benefiting from dirty tricks - the timely leak, for instance, of mysterious wiretap recordings of senior officials discussing the case led to it being dropped just days before he was due to become president.

Once in power, he was criticised repeatedly for appearing to stack the criminal justice system with loyalists, allegedly in order to keep the “Zombie” case at bay.

“That’s how Zuma operates. He has manipulated government institutions. Look [at] the National Prosecuting Authority,” says Bantu Holomisa.

The National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) has experienced a high - and much criticised - turnover of senior staff. In December 2017, South Africa’s High Court ordered the NPA boss, Shaun Abrahams, to step down and insisted that the president was too “compromised” to select his successor. Zuma is appealing against that ruling.

2005: Zuma with former South African President Thabo Mbeki

Of course, in his day ex-President Thabo Mbeki was accused of using the NPA as a political tool against Zuma.

But over the years, it's widely claimed, this case has fuelled Zuma’s taste for conspiracy, and victimhood.

He has long blamed his legal troubles on political rivals in the ANC, on opposition parties, and on “former colonial” governments who, he argued in a recent television interview, “look at some leaders in Africa as their enemies, and I’m one of those”.

Every new criticism, every allegation of corruption, now appears to reinforce Zuma’s apparent perception of himself as a target of racists and imperialists who are determined to thwart his struggle to free South Africa’s economy from the white businessmen who are still “monopolising every space of the economy”.

There is no doubt that South Africa is a profoundly unequal country, and the legacy of apartheid continues to skew the economy in favour of white people, but many people suspect Zuma is now portraying himself as a champion of “radical economic transformation” and enemy of “white monopoly capital” for self-serving reasons.

It is standing room only inside Johannesburg’s upmarket Hyde Park shopping centre. Middle-class South Africans, black and white, are waiting in polite silence for an evening book talk.

No-one can remember anything quite like it - the huge crowd, the sense that an old drama is being brought back to life.

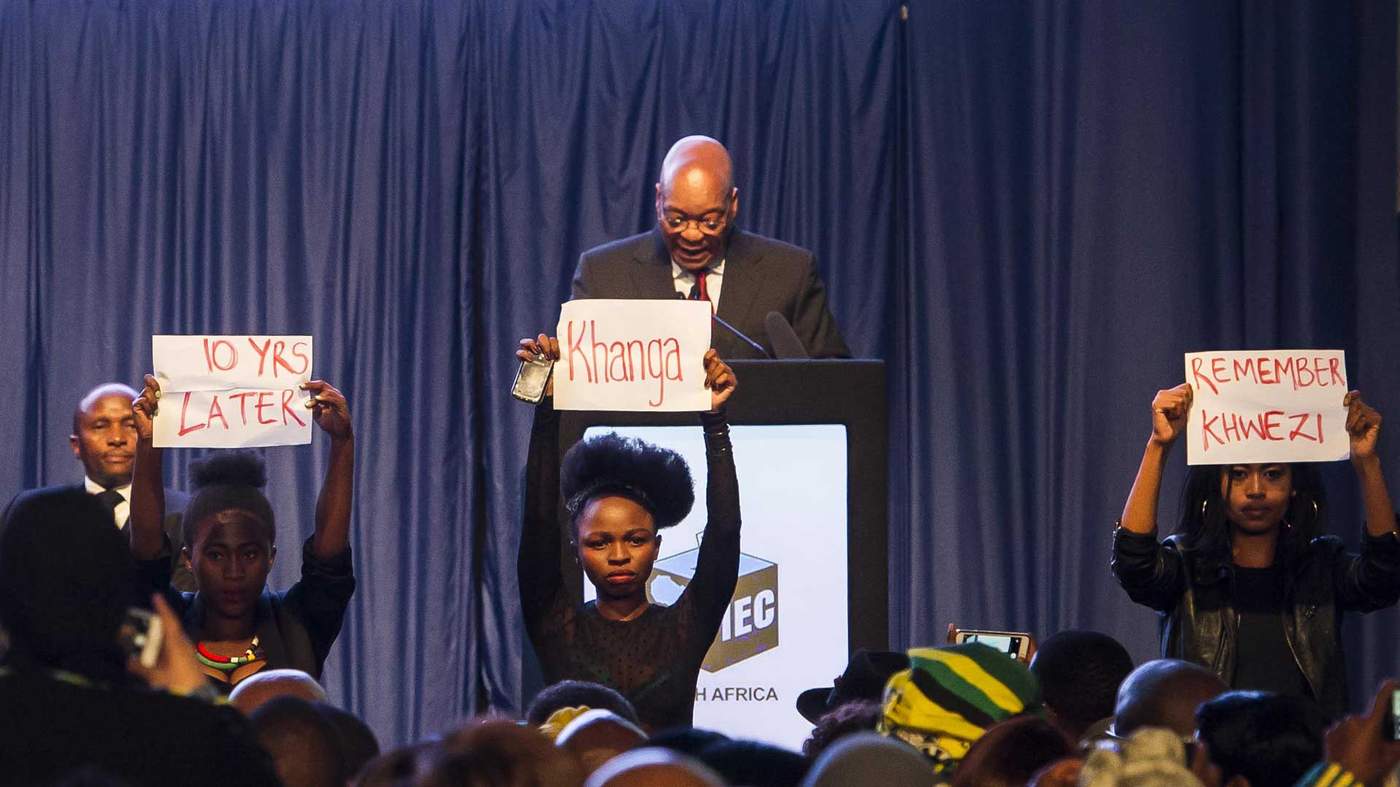

In 2006, Jacob Zuma was acquitted of rape.

Of all the stories about him, and all the allegations against him, this is the most personal, the most vivid, and the one some South Africans believe exposes their president’s true character in the most damaging way.

“This is a typical story of a young woman and a powerful man. And I just didn’t want Jacob Zuma to get away with it,” says the prominent local broadcaster Redi Thlabi.

She has written a book about Fezekile “Khwezi” Kuzwayo, who went to court to try to prove that she’d been raped by her dead father’s old friend, a man she considered as an “uncle”.

Fezekile “Khwezi” Kuzwayo accused Jacob Zuma of raping her

Something close to a collective shudder ripples through the mall as Thlabi begins to explore the notion of consent in a patriarchal culture.

A few weeks later the president's deputy and rival Cyril Ramaphosa brings more attention to the issue when he says that he believes Zuma’s accuser, prompting Zuma's office to state: "The court acquitted the president of the rape charges."

During his trial, Zuma was supported by a raucous crowd shouting “burn the bitch” and “100% Zulu boy”. Inside the courthouse, he insisted he and Khwezi had had consensual sex, and that he’d behaved in accordance with his patriarchal Zulu culture when presented with a woman “at that state” - in other words, sexually aroused.

South Africa is a violent country, and violence against women remains a national scandal, with more than 40,000 rapes reported to the police each year and a widespread assumption that the true figure is vastly higher.

But the story of Zuma’s rape trial has come to underline the divisions between rural and urban communities in a country still wrestling with issues of culture and chauvinism.

The judge acquitted him of rape, but condemned his behaviour as “unacceptable”. Zuma had told the court he’d had a shower after sex to “minimise the risk” of contracting HIV - a comment that would stalk him in mocking cartoon-form for years afterwards.

A political demonstrator mocks Zuma's “shower” comments

From the start, Zuma chose to see the case as yet another attempt by President Mbeki and his elitist, urban allies to frustrate the ambitions of a country lad - part of a pattern to humiliate him.

“Bring me my machine gun!” Zuma sang to his supporters outside court, immediately after the verdict. The words of the old struggle song were an explicit sign that he saw the trial in purely political terms.

“The public condemnation of [Khwezi] was so gleeful,” says the writer Sisonke Msimang. “It’s so emblematic of the way women are treated here, and shamed here.”

Khwezi was forced into hiding, fleeing abroad after her house was burnt down. She would return, quietly, a few years later only to fall ill and die, in 2016.

Zuma was, it must be stressed, found not guilty of rape, and Khwezi struck many as an unreliable witness.

But in the years since the trial, Zuma’s behaviour towards women has continued to trouble some South Africans.

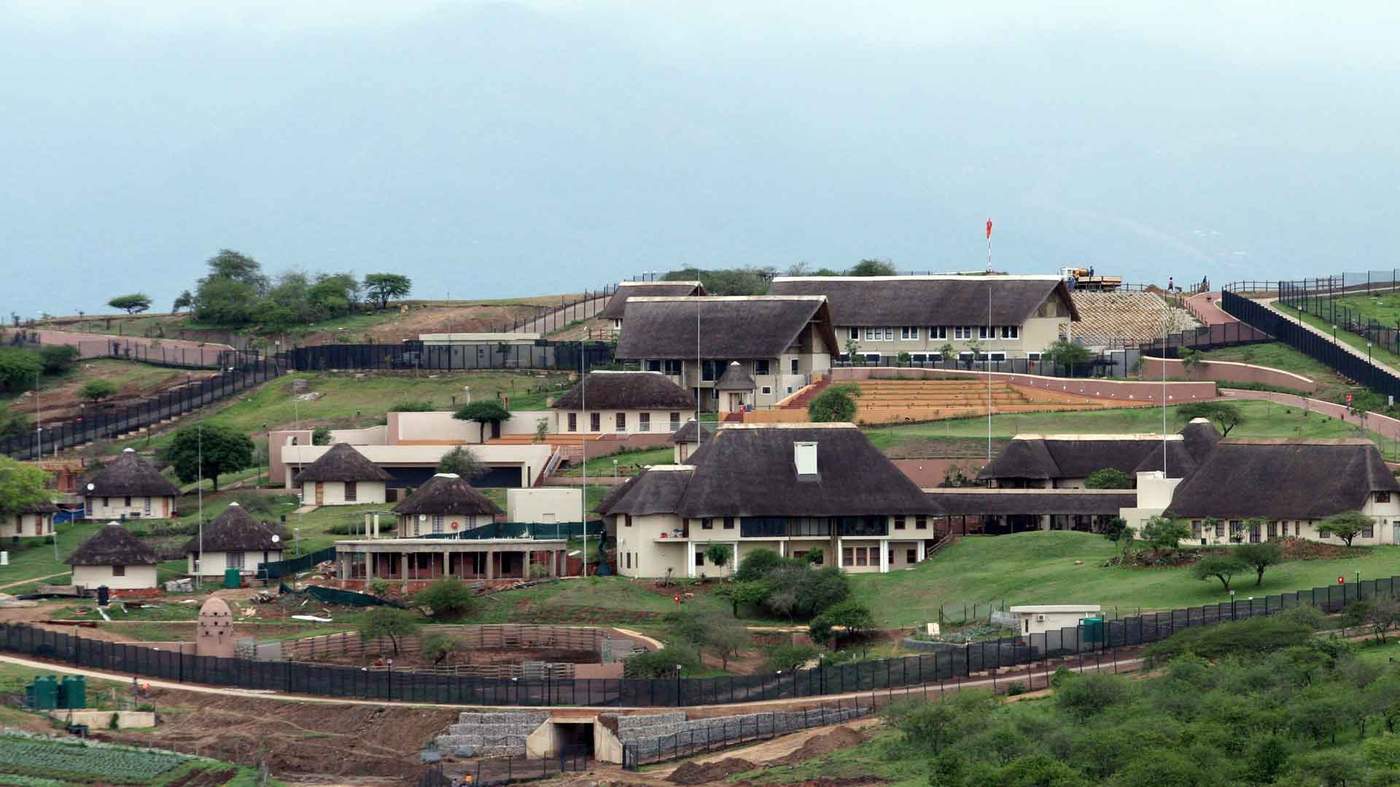

On a pale green hillside in rural KwaZulu-Natal, a cluster of conspicuously well-thatched buildings emerges from the surrounding countryside.

From a distance, it looks almost like a traditional African village, with round huts and an enclosure for the cattle nestling just below the brow of the hill. But if you approach the area on foot, you’ll quickly spot the high security fences and neatly paved roads, and if you look even closer, you’ll see a swimming pool, shaped like a spear tip, and a large amphitheatre surrounded by a maze of large buildings.

It is like wandering into a luxury resort.

This is Nkandla, Jacob Zuma’s private homestead, and the scene of an extraordinary scandal.

“Nkaaaaaandla!”

In 2012, a grinning Zuma told parliament that he and his family had paid for all the lavish upgrades to his home. He elongated Nkandla’s middle vowel to mimic and mock the accents of the white opposition MPs who were among those accusing him of illegally wasting taxpayers’ money on the refurbishments.

“I am not guilty,” he insisted.

It would take years of rival investigations, court cases, appeals and finally a damning statement from South Africa’s Constitutional Court to establish beyond doubt that many of the “security upgrades” - worth some 246 million rand ($23m; £13.8m in 2014) - that the government had paid for at Nkandla were nothing of the sort.

Zuma stood accused of improperly benefiting from a building programme that turned a comfortable array of traditional rural buildings into something that more closely resembled a five-star hotel. It is Zuma’s Versailles.

“The president has thus failed to uphold, defend and respect the constitution,” South Africa’s Constitutional Court concluded, pointedly citing the “cattle kraal, chicken run, swimming pool, visitors’ centre and the amphitheatre”. Zuma’s allies in government and parliament had tried, with increasingly comical contortions, to argue that these were essential security features.

Several officials described the swimming pool as a “fire pool”. “In order to eliminate or minimise potential risks and due to water supply which was erratic, a fire pool was decided on as the most viable option for firefighting,” said Public Works Minister Thulas Nxesi.

In protecting Zuma from proper scrutiny, parliament itself - the judges concluded - had “flouted its obligations” and broken the law.

Unlike the giant but opaque arms deal, Nkandla was something that every South African could understand.

Zuma finally conceded that unintentional mistakes had been made, and apologised for the “frustration and confusion” that had resulted. He reimbursed the state for some of the money spent.

But Zuma didn’t stand down as president. The majority of his party stood by him - through gritted teeth - as blame was shifted towards more junior officials.

“[President Zuma has] allowed the resources of the state to be used for the benefit of his family. He should stand down because he’s betrayed a constitutional responsibility that he swore to uphold,” says Sipho Pitanya, the prominent businessman, ANC stalwart and leader of the campaign group Save SA.

Zuma faces parliamentary questions about his Nkandla home, September 2016

“It’s the politics of patronage,” fumes Bantu Holomisa. “He rewards the people who would have challenged him by giving them cabinet positions. Many of these people who would have [spoken out] have a bone in their mouth, so they’re unable to bark too much.”

In private, Zuma’s closest aides still moan about their boss’s “stubbornness”, and about how a relatively minor issue - that might have been seen as a problem of inflated costs and a weak bureaucracy rather than overt greed - was allowed to turn into a festering, years-long controversy. Nkandla enabled the president’s critics to turn him into a caricature of a corrupt African “big man”.

It was the perception of a cover-up, not the crime, that did so much of the damage. He could, right at the beginning, have blamed the security services, apologised immediately for any confusion and paid up what he owed.

But some people admired his tenacity or saw him, yet again, as the rural chief being victimised by urban elites.

“He fought back on Nkandla because of the manner in which it was intially presented to him. The people who do the upgrades are from the state security apparatus,” says Jessie Duarte.

But in a country where many families wait for decades on government housing lists, or struggle in shoddy council homes or the ever-expanding tin shacks of South Africa’s “informal settlements”, Nkandla has become a byword for an increasingly pervasive culture of official entitlement and corruption.

Homeless people in a Johannesburg township

Nkandla was a prominent opposition slogan in the 2016 elections that saw the governing ANC’s share of the popular vote sink towards 50%, and key cities - Johannesburg, Pretoria, Port Elizabeth - join Cape Town by falling to opposition parties.

But if Nkandla seemed like a presidency-defining scandal, an even more serious one was poised to eclipse it.

In April 2013, a chartered Airbus A330 carrying 200 civilians touched down at the Waterkloof airbase south of Pretoria to an unusually extravagant VIP reception.

The plane was carrying guests from India to a lavish wedding at the Sun City resort. The host family’s name was Gupta.

Officials rolled out a red carpet and provided a huge police escort. They later told the media that they believed they were acting on instructions from, or anticipating the wishes of, the Guptas’ close friend “Number 1” - better known as Jacob Zuma.

The Gupta brothers had arrived in South Africa from India in the early 1990s, looking for business opportunities. They started in computers, prospered spectacularly, and in a canny move, hired two of President Zuma’s children to work for them.

The Johannesburg HQ of Sahara Computers, owned by the Gupta family

For a while the Guptas, in their vast compound in the old-moneyed Johannesburg suburb of Saxonwold, struck many as sharp-elbowed but relatively unremarkable figures - just one more family trying to muscle its way into the world of lucrative state contracts.

“Every human being has the right to have friends,” an indignant Zuma told parliament.

Then, late in the evening, on Wednesday 9 December 2015, President Zuma appeared on television to make an unexpected announcement.

Without explanation, Zuma informed South Africans that the highly respected Finance Minister, Nhlanhla Nene, was being removed. His replacement would be David Van Rooyen.

Who? Almost no-one outside the corridors of parliament had ever heard of him.

Zuma with his short-lived finance minister, David Van Rooyen

Nothing about the announcement appeared to make any sense. And the country reacted accordingly. The South African rand immediately plummeted. Billions of dollars were wiped off the stock exchange. And powerful figures quietly began begging President Zuma to change his mind. The newcomer Van Rooyen lasted just four days.

But the bizarre reshuffle remained unexplained until months later. Then Deputy Finance Minister Mcebisi Jonas issued his own explosive statement. He said he had been invited to the Guptas’ Saxonwold compound and offered the top job - finance minister.

“I will have to agree to co-operate with the Guptas. They offered 600 million rand, and 600 later,” Jonas later told me.

He turned it down.

Mcebisi Jonas claims to have been offered money by the Guptas

The Guptas were accused of seeking to buy control over one of the most important jobs in the country in a manner that strongly implied they had the president’s blessing.

“Essentially what it said is that you have a shadow state,” run by the Guptas and Zuma, said Jonas.

The Gupta family strongly denied the allegation and said they had never met Jonas. They later attacked an anti-corruption investigation. "Our cursory reading of [the report] shows the evidence gathered is riddled with errors and is subject to rebuttal."

Jacob Zuma and his son Duduzane, who was allegedly at the Saxonwold meeting, also denied it.

But before long, a vast haul of leaked emails appeared - apparently from the Guptas’ business empire - and began adding substantial flesh to the claim that the Guptas now wielded outrageous power within the South African state.

Some of those implicated have reportedly said the emails are genuine, but others have raised doubts.

The Guptas have said that the emails are not authentic and they strenuously deny any suggestion of corrupt behaviour. They have submitted sworn affidavits to the contrary.

The emails are ostensibly devastating. They appear to show that other ministers, and key figures at giant public companies like the power utility Eskom, were being groomed and co-opted by the Guptas.

There were lavish foreign trips to Dubai and numerous other perks.

To many in South Africa, it was obvious that a criminal investigation had to follow.

But the NPA has seemed to drag its feet. Its most recent leader, Shaun Abrahams - now ordered to step down by the High Court - was routinely mocked as “Shaun the Sheep” by opposition politicians and commentators who felt his true loyalty was to the president, not justice.

The NPA has vehemently denied that Abrahams is a puppet. “Those perceptions are really unfair. People should at times come with empirical evidence and say this is what the national director has done for us to come to this conclusion,” said NPA spokesman Luvuyo Mfaku.

New information on the extent of the Guptas’ alleged influence over Zuma has attracted the attention of investigators in the US and Europe. The FBI and Britain’s Serious Fraud Office are looking into claims of links to the Guptas’ business empire.

Zuma has angrily denied that the state has been “captured”. Instead he blames “foreign culprits” who have paid money to his political rivals “so they can help promote the interests” of Western governments and capital.

It’s an explanation that has been enthusiastically endorsed by the Guptas themselves, and by some radical voices in South African politics now championing the drive against “white monopoly capital”.

But Zuma’s rival Cyril Ramaphosa spoke openly of “a plan to implement grand-scale corruption, which was all-pervasive”.

“This saga left me with a very deep sense of grief and anger,” says Murphy Morobe, an ANC veteran who’d once spent time, like Jacob Zuma, imprisoned on Robben Island.

The impact on South Africa has gone far beyond the realm of politics. The allegations have damaged the economy and currency.

Ratings agencies now cite political uncertainty as they downgrade the country’s investment prospects ever closer to “junk” status.

White plastic chairs are flying back and forth across a crowded hall in Eastern Cape, hurled by rival members of the ANC.

In the grainy footage of the incident, filmed on a mobile phone, the chairs almost remind one of birds swooping and fighting over a brightly coloured rubbish tip.

Somehow that image feels appropriate for a grand liberation movement that is now tearing itself apart in what, to many, looks like an increasingly sordid, vicious, battle over the spoils of patronage and power.

ANC officials have been shot dead - particularly in Zuma’s home province of KwaZulu-Natal - and whistleblowers have been driven out of the party.

“There is a war that is silent,” one ANC MP, Makhosi Khoza, told me earlier this year, soon after declaring she’d received death threats for backing a parliamentary motion to remove President Zuma from office. She has since left the party to form a new one.

“South Africa is both a dictatorship and a kleptocracy. Maybe as a liberation movement we have reached a dead end,” she concluded.

“Ehe... ehehehehehe!”

In early October 2017, President Zuma chuckled his way through some rambling, genial remarks to a visiting delegation in a Pretoria conference chamber. Sitting opposite him was Zimbabwe’s 93-year old President Robert Mugabe, still in power, slumped in his seat and smiling at Zuma.

When it was his turn to speak, Mugabe drew parallels between his own liberation movement, Zanu-PF, and the ANC. Then, going off script, he worried out loud - and presciently, in terms of his own immediate political future - whether the “future is rendered into nothingness, torn apart”.

Standing behind a velvet rope, watching the two elderly men flanked by their cabinets, I was struck by the over-riding sense of weariness emanating from the chamber. These were tired old men, trudging through another choreographed encounter, each approaching the end of his term - although Mugabe could have had no inkling of the dramas that November held in store for him.

Both men have been rightly celebrated for remarkable achievements. Both are stubborn, courageous, and in their own ways, profoundly committed to their respective countries. And yet both men’s accomplishments are now overshadowed by their own individual flaws.

With Mugabe it was his brittle arrogance, his ruthless determination to hold on to power and, ultimately, his crass and insecure attempt to install his wife as successor.

Zuma is a warmer-blooded figure. But his profligacy, his philandering, his vanity, and his hard-learned habit of seeing a conspiracy behind every criticism, have turned him into democratic South Africa’s greatest cautionary tale.

In a rare television interview, Zuma tried to flesh out his achievements as president. But as usual, he quickly found himself distracted by talk of plots and intrigue.

“It is a reality - I was poisoned. Some people wanted me dead,” he said of a mysterious incident.

Zuma seemed to insinuate that unnamed “former colonial countries” might be behind the poisoning. “They’re trying every method to weaken the ANC,” he claimed.

“There’s nothing, nothing factual. It’s just political... political propaganda,” he fumed of the mountain of allegations that have piled up at his door.

“It’s easy to criticise.”

It is indeed. It is tempting to wonder how Jacob Zuma will spend his retirement. Relaxing, perhaps, with his family at Nkandla. Or, as is beginning to seem more likely as he loses a string of court rulings, continuing the long legal battle to clear his name.