Three years ago, Alex Abrahams was flicking through the pages of a newspaper when he chanced upon the advert which would end up changing his identity.

“I saw that the governments of Spain and Portugal had passed restitution laws to offer citizenship to the descendants of those expelled by the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions at the end of the 15th Century and beginning of the 16th Century. I thought: ‘Wow, that’s amazing!’”

Alex Abrahams

Alex, a 32-year-old lawyer, is British and has lived in London all his life. Like many British Jews, his ancestors came to the UK in the early years of the 20th Century to escape political and civil unrest in Europe.

Alex’s mother’s family came to Britain in 1914 to escape war in the Balkans. They hailed from Salonica - now modern day Thessaloniki in Greece - where they had lived for generations. But it was well known that the Jews of Salonica had settled there after being expelled from Spain and Portugal centuries earlier.

Alex recalls his grandfather telling him never to forget that he was a Sephardi (the name for Jews who hail originally from the Iberian peninsula).

Harry Assael, Alex's grandfather

“It’s part of my identity” he explains. “My grandfather, even though he was born in London, spoke to his family in Ladino. It’s medieval Spanish with some Portuguese pronunciation, infused with bits of Turkish, Italian and Hebrew.”

The inheritance was also culinary, as Alex recalls: “He and my grandmother used to cook something called bimuelos during Passover. They’re basically doughnuts made out of matzah.“ Alex laughs and mischievously adds: “They’re OK if you put honey on them.”

Three years on from seeing that advert, Alex has just become a father for the first time. He’s also in the process of becoming Portuguese, despite only having been to the country twice (once for his own stag weekend).

Alex on holiday in Portugal

For him, it’s a way to formally recognise a key part of his identity. “I know it sounds like an incredibly tenuous link considering how many generations of the family you have to go through from essentially the Middle Ages till now. But half of my family comes from that community and these traditions. I think if my grandparents and great-grandparents and their ancestors were alive today, they would take up the opportunity too.”

The streets of Lisbon’s Alfama district are winding, cobbled and atmospheric. Tourists are drawn to the area for a sense of what the medieval city would have been like (as well as some celebrity spotting - Madonna has a house in Lisbon, and can occasionally be seen eating in local cafes).

Ruth Calvao, from the Centre for Jewish Studies Centre in Trás-os-Montes, is gesturing to a very old, rough-hewn stone wall providing shade from Lisbon’s strong spring sun. Despite its obvious age, it still looks like it could withstand any kind of modern military attack.

This is the site of the one of the city’s old Jewish quarters, nestled into the side of the old city wall. A street sign says Rua da Judiaria. The story that ends with Alex Abrahams begins in neighbourhoods such as this.

In 1492 the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, issued the Alhambra Decree, expelling Jews from the Spanish kingdoms of Castile and Aragon. Tens of thousands of Jews sought refuge over the border in Portugal.

A Portuguese priest, Andrés Bernáldez, observed at the time how the refugees “walked along the roads and over the fields with great difficulty and misfortune, with some of them falling, some of them dying, others being born and every single Christian felt sorry for them.”

At the peak of this influx, it’s estimated that up to a fifth of Portugal’s entire population was Jewish. Ruth - who was born into Catholic aristocracy but later converted to Judaism - describes the refugee crisis: “All the Jewish quarters were overflowing because of all the people coming in all the time.”

In 1495, Manuel I ascended to the Portuguese throne. Although first seen as friendly towards the Jewish population, Manuel wanted to marry Ferdinand and Isabella’s daughter, the Infanta of Aragon. As part of the marriage contract, the Spanish rulers insisted Manuel copy their strictures on the Jews of Portugal.

On 5 December 1496, Manuel ordered the expulsion of all Jews who would not convert to Catholicism. Some did leave but as the policy took force, Manuel vacillated and even sought to delay the departure of the Jews.

Ruth Calvao

“Manuel was very ambiguous about this,” says Ruth. “He knew much of Portugal’s finances were in Jewish hands – such as the ports, the trades and the construction of the caravels (ships) that helped with the discovery of the New World. He didn’t want the Jews to leave so that’s why he staged forced conversions instead.”

In the centre of Lisbon, Ruth shows where a mass conversion involving 20,000 Jews took place in late 1497. Herded together in a courtyard, they were doused with baptismal water. These converted Jews became known as “New Christians”.

Despite their conversion, New Christians faced limitations on their legal, financial and civil rights, as well as threats to their safety. Under Manuel’s heir, João III, the Inquisition was set up in Portugal in 1536, focusing on New Christians suspected of secretly practising their old faith. It’s thought more than 40,000 individuals were charged by the Inquisition, which lasted until 1821 although the last public trial was in 1765.

An engraving shows the burning of heretics by the Portuguese Inquisition

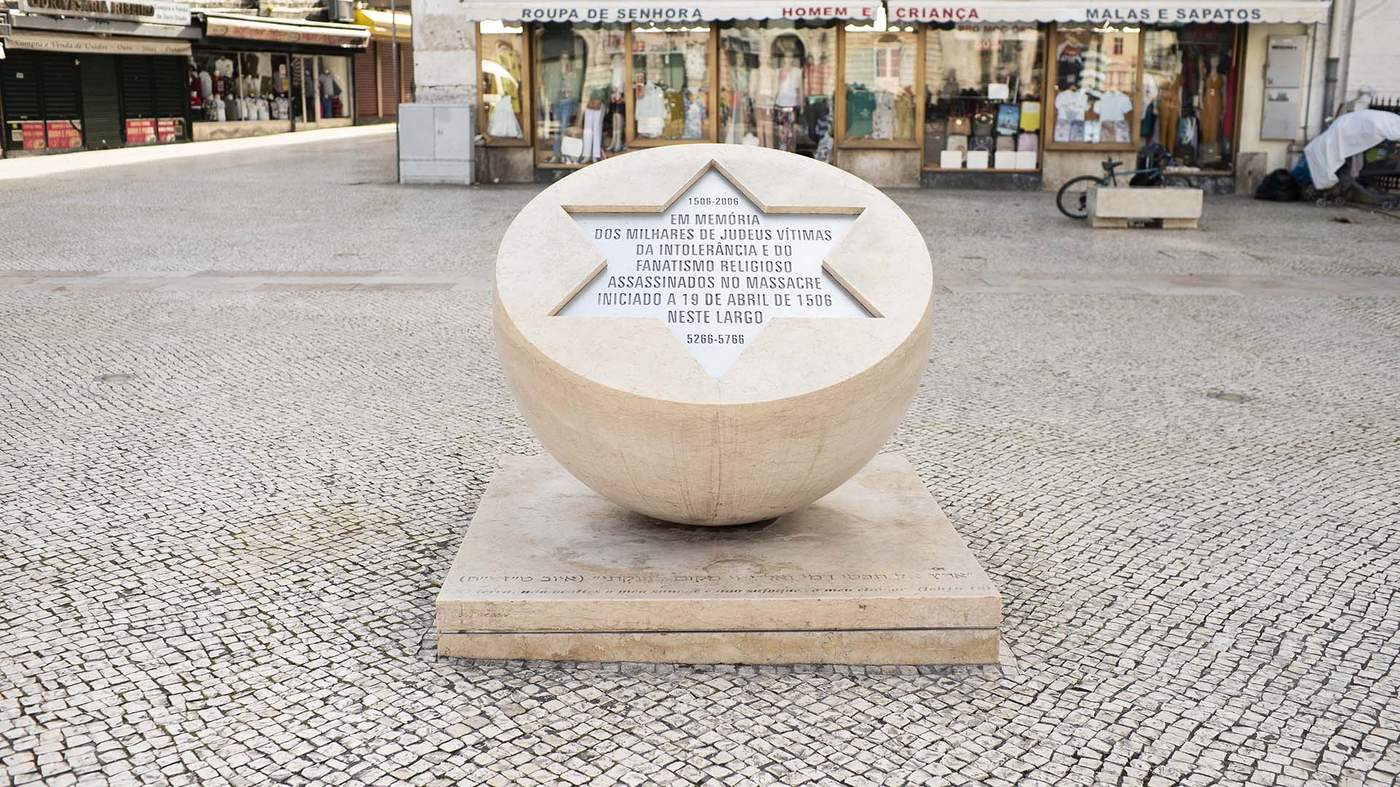

In 1506 a Lisbon mob invaded one of the city’s old Jewish quarters and massacred around 3,000 people – including women and children. It’s commemorated by a monument outside the Church of São Domingos - half of a stone orb with a metal Star of David set in it. It was unveiled in 2006 and calls for a spirit of tolerance in place of fanaticism.

The massacre set off another wave of emigration. The Ottoman empire, under Sultan Bayezid II, saw the dividend in offering refuge to exiled Jews - including Alex’s ancestors in what was then Salonica.

In 2013, Portuguese MPs unanimously passed a law allowing the descendants of Sephardic Jews to apply for nationality in Portugal. The bill was the idea of the country’s former health minister, Maria De Belém Roseira.

“When I was in high school and I read history, I never understood why Portugal had institutionalised the Inquisition.” she says. That nagged away at her over the years until she decided to do something about it.

“You cannot make things the same as before. But you can say it was a mistake and it was unacceptable. When we have the power to repair an injustice, we should do that.”

Maria De Belém Roseira

Maria insists that the events of the 15th and 16th centuries are still relevant to today’s politics: “We cannot sign international treaties on human rights, tolerance and equality if we persecuted people because of their beliefs. In politics, you have to give the right signs.”

Spain also passed a similar law but it decided to place a time limit on applications and it required applicants to pass a language test. “Our law was broader,” says Maria, “This was something that happened five centuries ago. So we wanted to give people the opportunity to look into their roots and their families. This is not a problem of time.”

For that reason, many Sephardic Jews have chosen to apply for Portuguese citizenship. In any case, many of their ancestors would have crossed the border from Spain to Portugal as refugees.

Today Ruth has lots of groups contacting her from these diaspora communities – especially from Turkey. She’ll be showing ten Jewish Turkish families around the Porto area this summer. “They really want to see their roots,” she says. “It’s so lovely.”

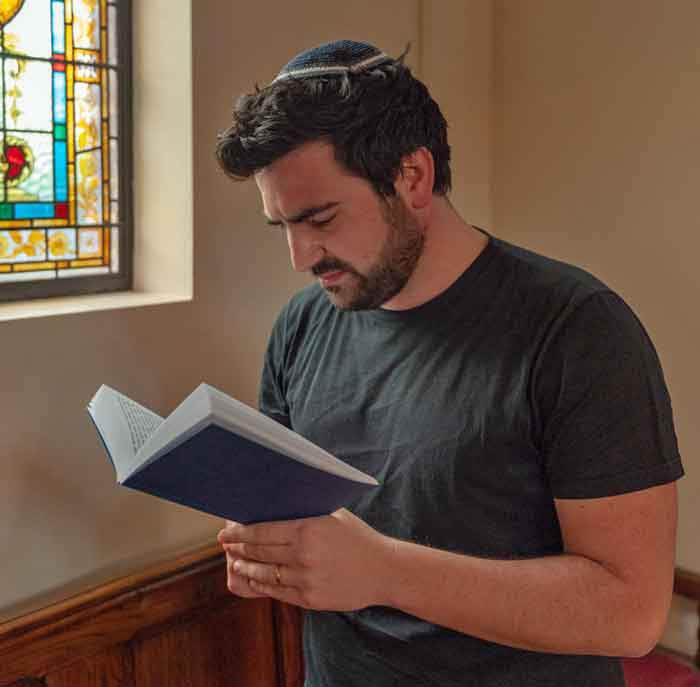

Lisbon Synagogue was built in the early 1900s appropriately enough by Jews who had returned from a long exile in Morocco and Gibraltar. These returning Jews originally worshipped in their homes but as their confidence as a community grew, so did their desire for a proper place of worship.

The building has wooden pews with 12 elegant pillars round the edge supporting an upper gallery. At the front, there’s a frieze of glittering mosaics over the ark which contains the Torah scrolls. Above that, carved into stone, is the inscription in Hebrew: Know Before Whom You Stand.

The staff have been surprised by the number of applications for Portuguese citizenship. To help the government, they have been issuing certificates to those who can prove they have Sephardic ancestry. After that, applicants must apply via the Ministry of Justice for the formal naturalisation process.

Gabriel Steinhardt (below) is the President of the Jewish community in Lisbon. Although he himself is descended from Ashkenazi Jews (from eastern Europe and Russia), he was born in Portugal and so the new nationality laws have an emotional pull.

“I call it a law of return,” he says, “allowing Jews to get back a passport that they normally would be holding if their ancestors had not been forced to leave. It’s the closing of a circle of reconciliation between the Jews and Portugal.”

Since 2015 (when the laws came into effect) around 30,000 people have applied to the Ministry of Justice. Out of them about 25% - or just over 7,000 - have already got Portuguese nationality. The largest group of applicants is from Israel, then Turkey and Brazil.

One of those who knows most about the motivations of applicants is Yoram Zara, an Israeli immigration lawyer.

He says large numbers of Jewish Turks applied early on because of political instability at home. “They were worried about their own well-being; about Turkey becoming less democratic; more Islamic and less predictable. They wanted an insurance of sorts.”

As for the Israeli applicants, Yoram says often they apply because “an EU passport is a bit of a status symbol – to walk through the short line at border control”. But he also adds a more serious point: “It wasn’t that long ago that Jews were persecuted and if you had the right papers you could escape your destiny. So there’s a feeling that having another identity can’t hurt.”

What about Brexit and British applicants?

“The day the referendum results were announced my phone didn’t stop ringing and the emails didn’t stop landing in my inbox,” says Yoram. “It was a kind of panic.” He says it’s calmed down a lot now.

Gabriel Steinhardt also says that interest from the UK has not been that high: “The numbers are relatively small - just 1 or 2%. So we’re talking hundreds, not tens of thousands”.

The synagogue in Porto, which has dealt with many of the UK applications, says it’s approved 419 certificates of Sephardic ancestry to Britons since the law came into effect.

Proving Sephardic heritage can happen in several different ways. Many people have been able to draw up family trees using records from established Sephardic communities such as the Bevis Marks Synagogue in the City of London and the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam.

If, like Alex, you have strong family links to such a community you might only require a letter from a Rabbi and a family document such as a ketubah or marriage certificate.

Kadoorie Mekor Haim Synagogue in Porto

Gabriel Steinhardt has seen some British families trace their family roots right back to the 17th Century but he admits that is an exception. There’s even been some talk of individuals presenting rusty keys from ancient family homesteads as evidence.

“I know of at least two cases of Jews from Turkey that have kept keys from homes in Portugal and transmitted them over 500 years from generation to generation,” he says. “Obviously, those houses do not exist any more, nor do they know where the houses were. But it’s a very moving story.”

Other pieces of evidence sent in have included photographs of gravestones and recordings of songs sung by parents and grandparents perhaps in Ladino, Spanish or Portuguese.

By way of a demonstration, Rabbi Natan Peres from the Lisbon Synagogue sings a traditional table prayer in Spanish called Bendigamos or Let Us Bless: “It’s an example of how the Jews who left the Iberian Peninsula kept a cultural and spiritual connection back to their homelands.”

Gabriel explains that often family names are a good clue, combined with the regions people have come from - for example, the established diasporas in Turkey or Morocco.

“We understand, and the Portuguese government understands, that except for some very rare cases it is hard to be 100% sure. But it is possible – with a high level of certainty - to say that the person applying is a descendant of a Sephardic family.”

Gabriel says there are now only about 1,500 practising Jews in Portugal although in the last census 5,000 people identified as Jewish. It’s one of the smallest populations in the EU.

“Our big hope is that perhaps 1% of those who’ve been approved for nationality will stay in Portugal amongst us and make our community grow a little bit. That would be fantastic.”

Etel Sason is a retired university lecturer from a Turkish Sephardic family. She now fills her time with volunteering in a local high school in Istanbul and part-time healing work at a wellness centre. She loves her life as it is, but even at the age of 61 there’s a restlessness there – something pulling her back to the Iberian Peninsula. Etel tells me her ancestors had lived in Toledo, Spain until 1492: “They were forced to leave and part of us still feels we belong there.”

Etel Sason

Etel and her family got their Spanish citizenship in 2016 through its version of the Sephardic ancestry scheme. She’s now considering splitting her year between Turkey and either Spain or Portugal - possibly Lisbon.

“Something calls me – perhaps my genes are telling me I have lived there before. There are so many similarities. Even the cookies they sell in Portugal – they are the same cookies that were baked by my grandmother. The soup too – it’s my grandmother’s soup!”

Perhaps the most uncanny thing is that Etel says she can pick up the languages of Spain and Portugal just like that. “It’s miraculous. I’ve never had lessons and I don’t know how to write those languages but I can understand almost everything.”

Etel’s parents, like Alex’s grandparents, spoke Ladino at home and there’s enough overlap to help Etel get the gist of what Spanish and Portuguese people are saying to her.

“It’s so easy to feel at home in Portugal. Lisbon is really like a smaller Istanbul. Whenever I visit I feel the call.”

Etel will be renting a summer home in Lisbon this year and she tells me she knows other families who are moving there permanently.

She admits it’s not just their Sephardic roots which make it an attractive prospect. It’s also the fact that Portugal and Spain have good universities and business opportunities as well as a good standard of living compared to more expensive European cities. A sunny climate, of course, also helps.

Not every member of Alex Abrahams’ family shares his enthusiasm for becoming Portuguese. “My Mum thinks I’m nuts,” he confesses, even though it’s her family roots which give him the right to claim Portuguese citizenship in the first place. “She thought it was ridiculous when I first told her but as more people have applied, she’s started to take it more seriously.”

When he decided to apply, he was able to delve into the family archives to prove his ancestry. He is lucky to have such a well-documented family.

Alex has a picture of his grandparents getting married in the Holland Park Synagogue, and he even has a pristine copy of their marriage certificate - in Hebrew but with Ladino phrases in it too. His application included a copy of this document alongside a letter from the synagogue’s rabbi, testifying that his family had strong historical links to the congregation there.

Fortunée Stella Amar

Interestingly Alex’s family records also contain a miniature portrait from the 18th Century. It shows a woman in local Sephardic dress from Morocco. Alex tells me this is Fortunée Stella Amar – his seven-times great aunt. She is from his maternal grandmother’s side but it’s yet another sign of his Sephardic roots. It’s a beautiful but fragile picture. Thankfully Alex didn’t need to part with it for his passport application.

Alex still has the documents to show how his great-grandparents were exempted from the Aliens Restriction Order controlling their movements. The Home Office was satisfied that because they were originally a family of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula they posed no internal threat to Britain.

So the family stayed. Alex’s grandfather, Harry, was born in West London in 1915. He’s the man who told his grandson never to forget his Sephardic heritage.

Following the Brexit vote in 2016, many British citizens applied for second passports. An estimated 200,000 applications for an Irish passport were made by UK citizens in 2018.

Alex says that Brexit played some part in his decision: “It wasn’t just airport queue time. Brexit was the catalyst but I would have done it anyway.”

Alex says he’s worried by a resurgence of what he calls ethno-nationalism: “It is frightening. I know that’s not representative of most Brexiteers, but it harks back to previous eras and I think many Jews are scared by that aspect because it never bodes well for them.”

He says he’s also concerned about the “conspiratorial language” of some left-wingers in the UK: “They do have a problem with modern Jews,” he says. “They don’t think they can be victims of racism. So I do worry about the world my children will grow up into if that becomes the prevailing politics.”

His growing family has also been a factor in obtaining an EU passport at an uncertain time in British history: “I’ve been thinking about the opportunities afforded to my son and whether he’ll be at a disadvantage.”

Alex describes himself as a “proud Brit and a proud Londoner” and he insists he is not planning to up sticks and leave. But he did think about freedom of movement when he made his application in 2016: “Dual nationality is hopefully not a taboo. You can have two parts of your identity expressed through your passports.”

Alex has spent about £2,500 on his quest for Portuguese citizenship. The application itself didn’t cost much but he’s had to employ a lawyer in Lisbon and many documents had to be notarised or sent by courier. All that adds up.

The process has also taken about two and a half years and it’s still not officially over – he’s waiting to have his details written in the Portuguese birth register. After that, he’ll be able to get a citizenship card and passport.

He’s already told me he has no immediate plans to move his growing family. But he wouldn’t rule it out altogether either.

“There’s the possibility that this isn’t just a symbolic thing that Portugal is doing and that Jews will move there and rebuild these ancient communities. That would be incredible - an amazing part of Jewish history.”

He points out his family was in the Iberian Peninsula and then the Ottoman Empire for longer than it’s been in Britain:

“Empires change, cultures move on and identities change too.”

He’s still waiting for the actual piece of paper – or email – that tells him he’s officially Portuguese as well as British. What will he do to celebrate when it finally arrives? “I will properly invest in a Portuguese language teacher,” he laughs, “because the app I’m using isn’t that great!”