In January 2015, four days after the terror attack on the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, an estimated 1.5 million people marched through Paris.

Viktor Orban was one of 40 world leaders at their head, standing in solidarity for freedom of expression and against terror.

2015: World leaders march through Paris after the Charlie Hebdo attacks

Different countries drew different conclusions from the Charlie Hebdo murders, and later terror attacks.

Orban was clear from the first moment who to blame. Immigrants.

The troubled family background of the perpetrators, their upbringing in an orphanage, the radicalisation they succumbed to - all these were of no interest to Orban.

He told Hungarian TV: “We will never allow Hungary to become a target country for immigrants. We do not want to see significantly sized minorities with different cultural characteristics and backgrounds among us. We want to keep Hungary as Hungary.”

It was a narrative that Orban had used before but then started to exploit tirelessly to win votes at home.

In 2015 and 2016, in addition to a wave of terror attacks, Europe faced another challenge - the arrival of hundreds of thousands of migrants and refugees.

By equating migrants with terrorists Orban tried to offer both a simple explanation and a simple solution.

Most of those coming were not refugees, fleeing war and persecution, he explained. They were economic migrants wanting a better life in Western Europe.

His message struck a chord with many Hungarians.

Orban asked his population in a referendum in October 2016 whether they wanted the EU to “impose migrants” on Hungary. He got a resounding “no” from the 41% of the electorate who cast a valid vote, although that turnout was too low to make the final result count.

Votes being counted in the 2016 referendum on migration quotas

Hungary’s population has long been falling - 30,000 people a year, equivalent to the loss of a small town.

The solution is not immigration, but rather to encourage Hungarian families to have more children, Orban believes.

To understand why an anti-immigration agenda might be so successful, it’s necessary to explore Hungary’s history.

Less than 2% of the Hungarian population was born outside the country.

And Hungarians have long memories of foreign invasion - of being overrun by the Turks, the Austrians and the Russians.

In 1920, the Treaty of Trianon settled the post-World War One borders of Hungary, one of the successor states of the defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Hungary lost 72% of her territory, and 31% of ethnic Hungarians found themselves outside her borders as minorities in Romania, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

Hungary was also deprived of her multicultural communities - the many Romanians, Slovaks, Serbs, Croats and Ruthenians who had previously lived side-by-side with Hungarians.

In World War Two, most of her large Jewish population was murdered in death camps, and in the post-war deportations she lost many of the Germans who had settled in Hungary since the 18th Century.

Hungary had been emptied of all but her Hungarians.

There’s a historical and literary parable that Viktor Orban likes. Every Hungarian schoolchild reads Geza Gardonyi’s novel - The Eclipse of the Crescent Moon.

It's 1552 and the castle of Eger in northern Hungary is besieged by a huge Ottoman army. Captain Istvan Dobo and his tiny garrison defend the town and send the Turks packing. The hero is Gergely Bornemissza, an explosives expert who plays a central role in the defence of the fortress.

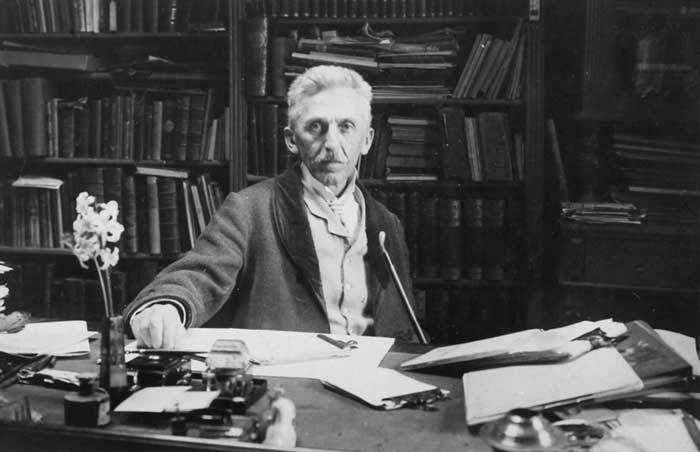

Hungarian author Geza Gardonyi (1863-1922)

Other Hungarian castles fell to the Turks in the following decades but only after inflicting such losses on the invaders that their advance into Europe faltered, then failed.

In September 2015 at the monastery of Banz in Bavaria, Orban conjured up the spirit of the 16th Century. He told his admirers from the German centre-right that he was just a captain, defending the outer castles from the same Muslim enemy, intent on swamping Christian Europe.

“If we want a Hungarian Hungary and a European Europe, and that is exactly what we want,” he said in a speech in October 2017 in Oradea, Romania, “then we must also want a Christian Hungary and a Christian Europe, instead of what now threatens us - a Europe with a mixed population and no sense of identity.”

Orban’s image of “mixed” versus “unmixed” populations provoked strong reactions. In February the UN human rights chief Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein called him a racist and a xenophobe. The Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto rejected the criticism as “unacceptable and inappropriate” and called on al-Hussein to resign.

They were on their way to the more prosperous countries of Western Europe. But Orban’s nightmare was that they might in future be sent back to Hungary by Vienna or Berlin.

In May 2015, the European Commission proposed compulsory quotas to redistribute asylum seekers. Orban was having none of it. “No-one will tell us who we let into our own house,” he thundered.

His answer was a fence. On 16 June 2015, Hungary announced the construction of a 175km (110-mile) barrier along the southern border with Serbia.

In the spring of 2015, Orban’s party Fidesz had lost two by-elections and the leader, according to his critics, saw the value of playing the migration card.

In the following months his party won back anything up to a million supporters, pollsters estimated.

The border fence (in red) spans Hungary's border with Serbia and Croatia

The fence was built by a combination of soldiers, prison inmates and unemployed people on community work schemes. It was completed on 15 September 2015.

By mid-October, a 40km extension was added along the border with Croatia. At 3m high, dug 1.5m into the ground, and topped with coils of razor wire, it was later reinforced with a second fence, a service road down the middle, a 900-volt electric current and night-vision cameras.

All of this was guarded by up to 10,000 police and soldiers.

“The old Iron Curtain was built against us, this one was built for us,” Orban told a press conference.

He introduced new laws to criminalise migrants.

Crossing or damaging the fence became a crime punishable by up to three years in prison. Most who do so are caught and summarily expelled from the country - through gates built into the fence.

One Syrian found guilty of inciting migrants to cross the border and throwing objects at police has recently been found guilty of “complicity in an act of terror” and sentenced to seven years in jail.

Two “transit zones” built into the fence at Tompa and Roszke, initially allowed 20 asylum seekers a day to apply. That figure is now down to two a day, according to the UNHCR.

The border near Roszke

In April 2017 the zones were enlarged into “container camps” where asylum seekers, including unaccompanied minors as young as 14, could be detained for many months.

In 2017, 3,700 were allowed to apply, of whom 1,300 were granted some kind of protected status. Most subsequently left the country. Integration programmes for the small number granted asylum in Hungary have been slashed or abolished.

Orban’s message is clear. Hungary is not open to migrants.

The phone rang in my 4th floor apartment overlooking the Kiraly Baths in Budapest. It was Miklos Haraszti, a well-known dissident. “I’ve got a young man here who wants to meet you.”

Later that day Viktor Orban was sitting in my flat, drinking tea from one of my chipped mugs. He was bearded, earnest, and keen to impress - explaining how he and his friends were setting up a new political movement.

It was to be called Fidesz - the Alliance of Young Democrats - and would be a rival of the Young Communist League.

It was March 1988 and Orban was 25.

At secondary school he had briefly pledged his allegiance to the Young Communists. But now they were falling apart.

The Party’s grip on power was always backed up by the presence of 55,000 Soviet troops. One would occasionally see them, always in small groups, at the zoo or railway stations, their broad-topped green felt caps looking like the baize on a miniature pool table.

But their effect was well understood. It was Soviet troops who had crushed the Hungarian attempt to break away from Moscow in 1956 under Prime Minister Imre Nagy. The threat remained in the years which followed.

When Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the Soviet Union in 1985, he publicly renounced the Brezhnev doctrine under which Moscow claimed the right to send military force to defend the Communist Party in any Warsaw Pact country.

This was a body-blow to the Communist leaders of Eastern Europe. They now realised that if the people ever rose up, the regimes might be unable to defend themselves.

They didn’t have long to wait.

Meanwhile, Hungary increasingly took over from Poland as the main seedbed of democracy in the region. Viktor Orban quickly became one of the bigger seeds.

He was born in Szekesfehervar in May 1963, a city 60km (37 miles) south of Budapest, and capital of Hungary in the Middle Ages. By the 1970s, it had recovered from heavy damage in World War Two, and boasted important bus and electronics factories, as well as a mechanised infantry battalion of the Red Army.

Orban grew up in the nearby villages of Felcsut and Alcsutdoboz, the oldest of three sons. He still has a weekend house in Felcsut.

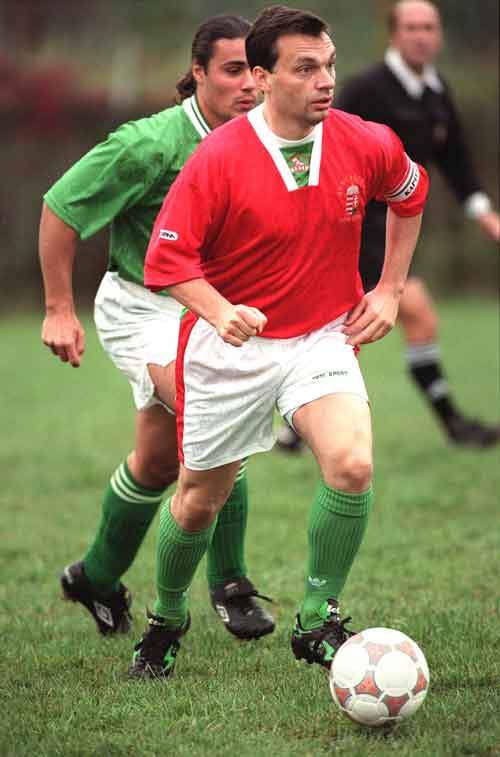

His father Gyozo was a member of the Communist Party and technical inspector in a local mine. The young Viktor was a bright pupil and a talented footballer. The trainer’s notes for the Felcsut team read: “Viktor Orban: Forward - quick thinker, fast shooter, dynamic passer - shows potential.”

Orban later told an interviewer: “I was probably the first in our family, when there was a choice of schoolwork or work in the garden, who chose to study.” He was beaten regularly by his father as a teenager for “disobeying him and being cheeky to his mother”.

His mother taught children with special needs.

Orban’s anti-Communism probably stemmed from the bullying and Marxist propaganda he was subjected to during his military service, according to one of his biographers, Paul Lendvai.

In 1982 he moved to Budapest to study law and political science at the Eotvos Lorand University in Budapest.

He quickly formed a tight group with his fellow students - who later became the core of Fidesz. There was a fierce loyalty among them, and according to their adversaries, “the best girls hung out there”.

Orban came from a Calvinist Protestant background but is thought to have been an atheist in his youth.

In 1986 he married university classmate Aniko Levai in a civil ceremony, despite her Catholic upbringing. They were both 23.

Orban with his wife Aniko Levai in 2016

Fidesz rapidly transformed itself from a youth movement into a political party, with a liberal ideology and an upper age limit of 35. “Rather than attacking Communist rule directly, we would create small islands of freedom, interconnected social circles and associations, which, when the moment came, could be connected to change the system,” wrote Orban.

In June 1989, anti-Communist and Communist reform groups agreed that it was time to rebury Imre Nagy and his colleagues, secretly executed by the Communists in 1958.

In front of a crowd of tens of thousands in Heroes Square in Budapest, Viktor Orban broke ranks with other leaders of the nascent Hungarian opposition, to demand that Soviet troops leave Hungary.

“If we are determined enough, we will be able to coerce the ruling party to submit to free elections. If we have the guts to will all of this, then and only then we shall fulfil the destiny of our revolution.”

In the taxi afterwards the Polish dissident leader Adam Michnik told him: “Viktor, you shouldn’t have said that.”

But while others on the stage were afraid of a coup against Gorbachev in Moscow, and hardline Communists returning to power in Hungary, Orban plunged in.

The last Soviet soldier left Hungarian soil in June 1991, as Fidesz activists waved triumphant banners beside their trains.

Fidesz won a respectable 9% in the election in 1990, but slipped to a disappointing 7% in 1994.

Orban saw a gap opening on the political right and seized it - dragging his liberal party to the conservative side, although several of his closest friends quit in protest.

Inspired by Germany’s long-serving centre-right Chancellor Helmut Kohl, from 1995 onwards Orban set about gathering everyone in Hungary who was right of centre under his own flag.

What mattered to him was to win power, and keep it, at any cost”

A conversation from the early 1990s illustrates Orban’s ambition.

“We were sitting in the Angelika cafe, across the Danube from parliament,” economist Peter Rona remembers. Orban was describing how he wanted to turn Fidesz into a modern conservative party, but Rona warned of the danger of abandoning the “modern” at the first sign of electoral trouble.

“‘I will not fall into that trap, but if necessary, so be it,’ replied Orban, to my surprise. What mattered to him was to win power, and keep it, at any cost.”

In the mid-1990s, while a Socialist-Liberal coalition ruled Hungary, Orban was becoming more conservative.

He had opposed the Pope’s visit to Hungary in 1991 and mocked Christian Democrats in parliament, but he now realised he would have to be a Christian.

His decade-long marriage to Aniko Levai was blessed in a Calvinist church ceremony in 1996. All his five children were baptised.

The 1990s saw dramatic change in Hungary.

Factories, agricultural land, forests, homes, and businesses were privatised. Many late Communist-era managers made fortunes overnight, but there were also opportunities for sharp-witted, younger entrepreneurs, unconnected to the old regime.

Foreign investment poured into the country, but a large part of Hungarian manufacturing was destroyed. Western companies didn’t want semi-obsolete industries. Unemployment leapt to one million.

The country was brimming with resentment - between the city and the village, the new rich and the new poor, and between nationalists and liberals. Many people felt that privatisation had gone too far, and that the national wealth had been lost.

Orban won the 1998 election, and formed a coalition government.

His government was viewed as moderately successful and quietly prepared Hungary for EU membership. Orban was stunned to lose narrowly to the Socialists in 2002.

“The nation cannot be in opposition,” he assured a mass torch-lit vigil by his supporters in the castle district in Buda, after conceding.

It was a turning point in his career.

That autumn Orban was introduced to Arpad Habony, a communications expert and a champion in the Japanese martial art of kendo.

“[Habony] taught him to change the way he dressed, and the audience he talked to,” says a source close to the government. “To create a new image for himself, to speak and act like an average Hungarian.”

To this day, Habony remains Orban’s communications guru, although he has no official role in the government, and does not appear on the payroll.

Behind the scenes, Orban’s old schoolfriend Lajos Simicska was building a financial empire that would also help Fidesz back into power. Simicska’s company specialised in concrete, steel, and tarmac. As Hungary built hundreds of kilometres of highway, largely with EU money, the cash flowed into the coffers of Simicska, and his party.

Orban was beaten again in the 2006 election. Finally in 2010, Fidesz swept back to power with a two-thirds majority in a country still staggering from the effects of the global economic crisis.

Orban during his successful 2010 election campaign

Orban went first to Brussels, to ask for more time to tackle the country’s excessive deficit. The cold shoulder he received there, and in Berlin, left him bitter towards “the Brussels bureaucrats”.

His government needed money. Private pension funds were diverted to the state. There were new taxes on bank transactions, mobile phone calls and text messages. The tax on the revenue of foreign-owned energy companies was doubled.

2010: A Fidesz supporter carries a banner reading “Thank you Hungary”

With a two-thirds majority in parliament, Fidesz was unstoppable, carving out a new state based on its own ideology. Orban pushed through a new constitution which stressed Christian-Conservative values - nation and family.

This new constitution stated that Hungary had lost its self-determination from March 1944 to May 1990 - the years first of Nazi then Communist rule - and so partially absolved Hungarians of guilt for the Holocaust. It also weakened the power of the Constitutional Court to act as a check on the power of the government.

Orban granted citizenship and the right to vote in Hungarian elections to more than a million Hungarians living in neighbouring countries. At the last election, 95% of those who voted backed Fidesz.

A new media law was passed, creating a powerful National Media Authority. Public TV and radio and the state news agency became government mouthpieces. Under international pressure, the law was amended. But a year later, in 2012, the Council of Europe criticised political influence over appointments to the authority.

Critics were purged from the civil service, state companies, schools and even hospitals. When I asked Orban before the 2010 election how many people he intended to replace if he won, he replied without hesitation “12,000”. It was as if he knew their names.

In 2014 Orban won again. The new election law, passed in 2011, turned the 44% won by Fidesz into another two-thirds majority.

Even his critics acknowledge grudgingly that he “got the country back to work”, though they challenge the way he did it. In 2010, only 54% per cent of Hungarians of active age worked - now the figure is nearer 70%.

Orban promised a million jobs in 10 years, and claims to have now reached 740,000. But 180,000 are employed in government work schemes, sweeping streets and clearing scrubland, with little training for the job market.

The boom in construction is fuelled by EU funds of €3-4bn a year. Massive state construction projects focus on football stadiums and the rebuilding of public spaces.

Many Hungarians undoubtedly feel better off than four years ago. Wages have risen at more than 10% a year. Annual growth is over 4% and unemployment is below 4%.

But there is a growing shortage of workers, as over 600,000 emigrated to other EU countries seeking higher wages.

Electronics companies cannot fulfil orders because of a shortage of IT engineers. Hospitals complain of a shortage of doctors and nurses. Loudspeaker announcements at train stations try to attract new train drivers. Restaurants and shops advertise in vain for staff.

Orban and his media lambast migration as both undesirable and stoppable, but Hungarian families are acutely aware of emigration.

There are allegations of corruption. The prime minister’s son-in-law, as well as a narrow coterie of ministers and businessmen connected to Fidesz stand accused of diverting public funds. Orban’s son-in-law denies any wrongdoing.

OLAF, the EU anti-corruption watchdog, is investigating alleged irregularities in contracts for the street-lighting of 39 towns. The most radical action the EU could take would be to suspend all payments until investigations are completed.

In the spring of 1986 a new sound could be heard in the secondary schools and libraries of Hungary - the whirr and clunk of photocopiers.

The Hungarian-born financier and philanthropist George Soros, who made a spectacular fortune after emigrating to the US, donated hundreds of them.

George Soros, pictured in 1991

It was about more than education. While teachers could copy pages for their classes, pupils could mass produce subversive pamphlets.

The young radicals around Viktor Orban were among the first to take advantage.

And that wasn’t the last time Orban benefited from the largesse of George Soros. The billionaire set up the first branch of his Open Society organisation in Budapest in the 1980s to support dissident groups. He also handed out scholarships liberally to a new generation of bright students.

In October 1989 Orban went to Pembroke College, Oxford, on a Soros scholarship.

From there, he watched the revolutions unfolding across Eastern Europe in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Bulgaria and Romania, then broke off his studies to hurry home to Budapest, to make sure he was in the front row of his own.

Then Orban was happy to accept support from Soros. Thirty years later he takes a very different view.

The Berlin Wall falls, 1989

Many non-governmental organisations (NGOs) have been targeted by the Fidesz government. They depend on contributions from philanthropic organisations like the Open Society Foundations.

These NGOs include Transparency International which examines state corruption, and the Helsinki Committee, which provides legal aid to the small number of people who still seek asylum in Hungary.

Soros’s support for groups like these has angered Orban.

In 2017, giant posters went up across the country, with a grinning Soros and the words “don’t let Soros have the last laugh”.

“National consultations” were launched, with questionnaires sent to all households in the country, blaming Soros and the groups which his foundations support for mass immigration to Europe.

George Soros was long silent but he hit back in June 2017 in a speech in Brussels.

Soros in Brussels, 2017

“I admire the courageous way Hungarians have resisted the deception and corruption of the mafia state Orban has established.” He praised the European Commission for taking action against Orban.

As well as the NGOs, a Budapest-based university became a symbol of the battle between the two men.

A new law restricting foreign universities was seen as an attack on the Central European University (CEU), part-funded by Soros. Fidesz officials took to calling it the “Soros university”.

After protests and international criticism, the fate of the university still hangs in the balance.

Those working in critical NGOs have been referred to as “the Soros mercenaries” in the government-controlled media.

“Soros is one of the most dangerous people in the world,” Andras Bencsik, editor-in-chief of the weekly Magyar Demokrata, and organiser of large pro-Fidesz rallies tells me. “Soros has caused bigger damage to civilisation than a world war.”

A “Stop Soros” bill, as the government refers to it, has already been tabled by parliament, to be voted on after the election. It could make the work of several groups impossible.

On Easter Friday Orban told state radio that his government had the names of 2,000 “Soros henchmen” and warned that they would be dealt with after he won the election.

That is likely to bring him into more conflict with the European Union, and its strongest member, Germany.

In November 2009, Viktor Orban paid a short visit to St Petersburg, to the congress of Vladimir Putin’s United Russia Party. It was a peculiar choice of trip for a man who had risen to fame in 1989 by telling Russian soldiers to get out of his country.

But the 2008 financial crisis had shaken Orban’s trust in the Western economic model. By “turning to the east” - including Russia, China, and Turkey - he looked for new investors whose willingness to do business wouldn’t be affected by disdain for his domestic actions.

Meeting in Moscow, 2010

He saw how the Germans, quick to lecture him about democratic issues, were quietly doing plenty of business with President Putin.

Hungary is heavily dependent on Russian energy. Giant pipelines, built in the Soviet era, channel it into Hungary across Ukraine.

Hungary’s lone Soviet-era nuclear power station at Paks on the Danube, was getting old. Orban was in the market for a brand new nuclear power station, Paks 2, and Putin was keen to sell.

Orban went to Moscow and signed the contract, despite studies suggesting that nuclear power would cost three times more than electricity bought from the European grid.

The Russians will both build and finance it via a massive loan. Full details of the contract were made secret by the Hungarian parliament for 30 years.

At about the same time, Orban agreed with the Russians to extend a 20-year gas deal, due to expire in 2016, on favourable terms.

“The prime minister’s strategy is to keep equal distance between two bears, the Russians and the Germans,” a close political ally of Orban tells me. “He sees the tragedies of Hungarian history stemming from being too close to one or the other. But Orban is not Putin’s puppet. In fact, Orban thinks he can manipulate Putin.”

Hungary’s economic fortunes are deeply intertwined with those of Germany. A quarter of Hungarian exports go to Germany, and 300,000 people work for German companies. The car industry alone provides 175,000 jobs in Hungary.

2012: Orban opens a Hungarian factory for the German car manufacturer Daimler

Relations with Angela Merkel have cooled noticeably since her last visit to Budapest in February 2015.

Since then, Orban has preferred to develop his contacts with German companies based in Hungary, and with individual German states rather than the federal government. He wanted “more understanding, a more business-oriented focus, and less criticism on human rights and political issues,” said Milan Nic, an analyst with the German Council on Foreign Relations.

Angela Merkel is said to distrust Orban

Even before the 2015 refugee crisis Angela Merkel regarded Viktor Orban as “a dangerous man”. Orban’s support for Merkel’s critics in the Bavarian Christian Social Union (CSU) - the sister party of her Christian Democratic Union - did nothing to improve their relations.

German diplomatic sources say Merkel now refuses to even pick up the phone if Orban rings. This is fiercely denied by Hungarian diplomats. Hungary’s loyalty to the EU and Nato, they say, is proven by Hungary’s decision to expel a Russian diplomat over the recent Skripal poisoning affair in the UK.

“There are other ways of showing solidarity with our European partners than taking in migrants,” says a senior government source, “for example by building fences to strengthen the outer borders of the EU.”

Senior politicians from Germany’s CSU have pressed Hungary to compromise on migration.

Part of the solution could be financial - countries that refuse asylum seekers, like Hungary, might give money to front-line states like Greece and Italy. Another option would be for Hungary to accept voluntary - not compulsory - quotas. But there are no signs yet of Orban backing down.

Orban insists that the EU pay at least half his €800m (£700m) bill for building and defending the fence on the border with Serbia.

Before Britain voted to leave the EU, Orban counted on it as a counterweight to French and German designs to create a stronger, deeper union.

Now he relies on the four Visegrad Group countries - Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Poland - to act as a counterweight, a champion of national sovereignty, in the east of the EU.

2016: Orban with fellow leaders of the Visegrad Group of countries (Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland and Hungary)

There is no European identity, Orban says, contradicting the assertions of German, as well as French leaders. But there is a central European one - between the two bears of Russia and Germany.

“What I admire most in Viktor Orban,” says his loyal champion, the journalist Andras Bencsik, “is his ability to predict the future.”

Bencsik compares him to a chess grandmaster who can see 25 moves in advance.

Viktor Orban has promised “a settling of accounts” after the election with those who mocked, criticised, or tried to undermine his rule. “Political, moral and legal” retribution will follow, he told a rally of 100,000 supporters.

Every Wednesday, Viktor Orban holds a cabinet meeting. Thursday is his reading day.

The Israeli author Yuval Noah Hariri’s Sapiens - A Brief History of Humankind is a recent favourite. Target Hungary by the British-based sociologist Frank Furedi is another. Boston Politics, by Thilo Schabert, a third. Natural Right and History, by the German Jewish emigre Leo Strauss, whose thinking strongly influenced a generation of Republican politicians in the US, is the latest addition to his coffee table.

What the books have in common is a pessimism about the future of Western liberal civilisation, and a fondness for strong leaders, rather than strong institutions.

“Orban concentrates harder than he used to, he’s not as jovial, as easy going as he was,” says Bencsik. “Those who call him ‘Machiavellian’ are mistaking that ability to concentrate, for something else.”

Budapest is a small city, and almost every year I bump into the prime minister, purely by accident. I was sitting in a cafe on Normafa, a popular hill overlooking Budapest, when Orban walked in without a bodyguard, looking for a table.

I greeted him and he replied: “Hello Nick. Are you still alive?”

Not the friendliest greeting, but I let it pass. We shook hands. His handshake is no longer firm, I noticed. In just the past four years he has put on a lot of weight.

I asked him about Hodmezovasarhely, where a recent by-election saw an independent candidate defeat the Fidesz favourite by gathering the entire anti-Fidesz vote behind him.

“It will certainly change the dynamic of the campaign,” he admitted.

But to the surprise of even his supporters, the Fidesz campaign focused on the “threat of migration”, instead of the economic achievements of his government.

Orban appeared rattled.

March 2018: Opposition activists at an election rally for the Socialist Party (MSZP)

“Orban runs the country like a city, in which he has a million workers,” says Sandor Csintalan, a friend of Orban’s former ally Lajos Simicska, who is now one of his chief foes. “If he wins again, the only way he can keep power is more autocracy. You cannot consolidate a system like this, because only fear and feudal relations hold it together.”

Viktor Orban has stamped his own personality on the map of Europe. He is admired across the world by people who want to defend national sovereignty from globalisation.

But how will history judge him? It depends whether he ends up on the winning or the losing side.

If the Visegrad 4 countries grow stronger, as a counterweight to Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel’s visions of Europe, he will feel reassured.

If his critics concede that he was right to identify migration as the “curse” of this age, he will claim victory.

But if future EU funds are linked to respect for European values, or if the Hungarian public grow weary of his authoritarian style, Viktor Orban will be left out in the cold.