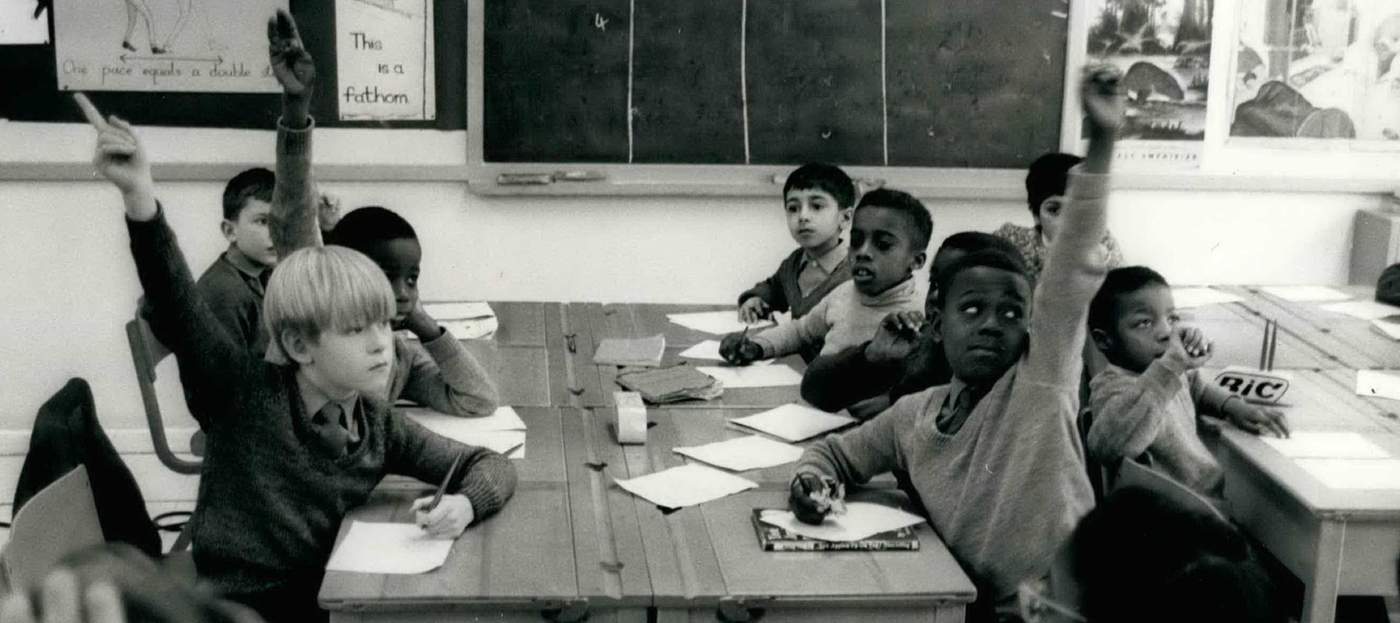

In February 1968, eight-year-old best friends Mike Edwards and Raymond Comrie found themselves thrust into the spotlight when their class at West Park School in Wolverhampton was interrupted by a visitor.

"I can remember the door was open, someone has come in with a camera," recalls Mr Comrie. The camera "ended up pointed at me and Michael".

To the boys it wasn't a big deal - they didn't even know why the photographer was there, or who had invited him into the school.

The media attention had been prompted by something Wolverhampton South West MP Enoch Powell had said earlier that month.

Two months before his notorious speech of April 1968, he had spoken of a constituent he said had told him how her "little daughter was now the only white child in her class at school" - and the press wanted to find her.

The school was never identified by Powell.

Indeed, there were doubts about whether it existed at all, but it was suspected the MP might have been referring to West Park.

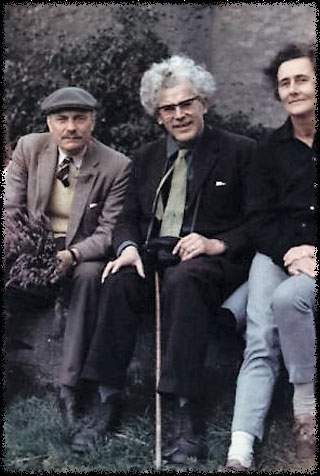

A few days before the speech, Powell went to see his good friend Clem Jones, the editor of Wolverhampton's Express & Star newspaper.

The two men had grown close over the years - their families lived only a few streets away and would go on outings together.

During the visit, somewhat cryptically, Powell told Jones: "When a rocket goes into the sky, the stars burst out. This time they are not going to fall to the ground, they are going to stay up there."

Jones's son Nicholas says that while Powell wouldn't reveal what he was going to say in the speech he promised he would soon be giving, the MP was clearly hinting at its likely impact.

"He was making the point it was explosive," Mr Jones says.

Nicholas Jones followed his father into journalism, going on to work as a BBC political correspondent

The friendship between the two men was beneficial for both. It gave Jones a heavyweight political contact, while Powell learned how best to promote himself and exploit the media.

"My father says that he claims to have been Powell's spin doctor, and Powell was a very good student," Mr Jones says.

On the day of the speech, Jones and his wife Marjorie were looking after Powell's daughters.

It was only at this point the newspaper editor actually saw a copy of it.

"He brings it home and my mother devours this. She reads the speech through and she is appalled," says Mr Jones.

"This crossed the line for her and was the end of a friendship.

"My parents had been very close [to Powell]... but from my mother's point of view, there was no going back."

For the newspaper editor, it was not just his personal life that would be affected.

Marjorie Jones was horrified by the contents of the speech

"All hell breaks loose and my father is in this terrible position," says Mr Jones.

"Ninety-nine percent of the letters are in support of Powell; he is trying to do a balanced job and it all gets really bumpy for him as an editor trying to produce balanced coverage."

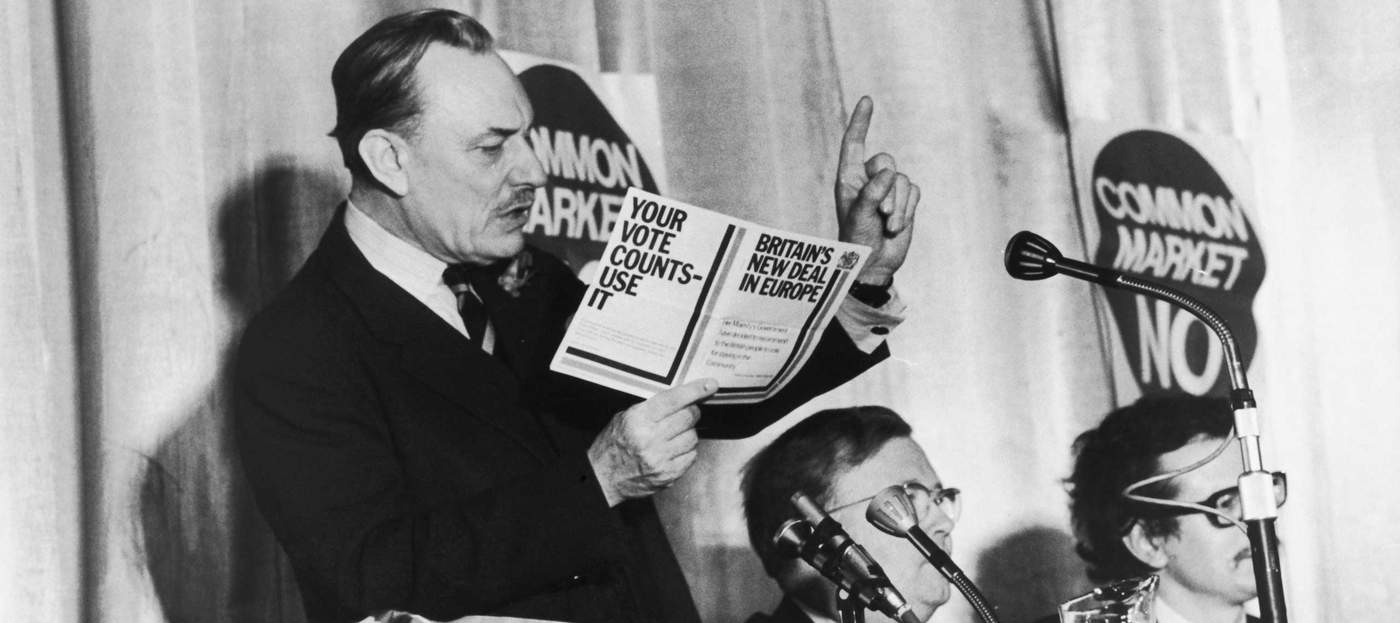

Enoch Powell gave the speech that was to define him, on 20 April 1968, at a Conservative Association meeting at the Midland Hotel in Birmingham.

Flanked by two stony-faced colleagues, Powell told his audience about what he said was an exchange with an unnamed constituent.

"If I had the money to go, I wouldn't stay in this country," the MP claimed he had been told.

"In this country in 15 or 20 years' time, the black man will have the whip hand over the white man."

And Powell didn't stop there.

"We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population," Powell said - his own words, this time.

It was "like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre," the MP continued.

"As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding: like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood."

With the television cameras filming - ATV had been tipped off about the contents of the speech - Powell went on to tell his audience of the only white woman remaining in a Wolverhampton street.

A war widow, he said, who was abused by "negroes", had "excreta pushed through her letterbox" and would be taunted by children he described as "charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies".

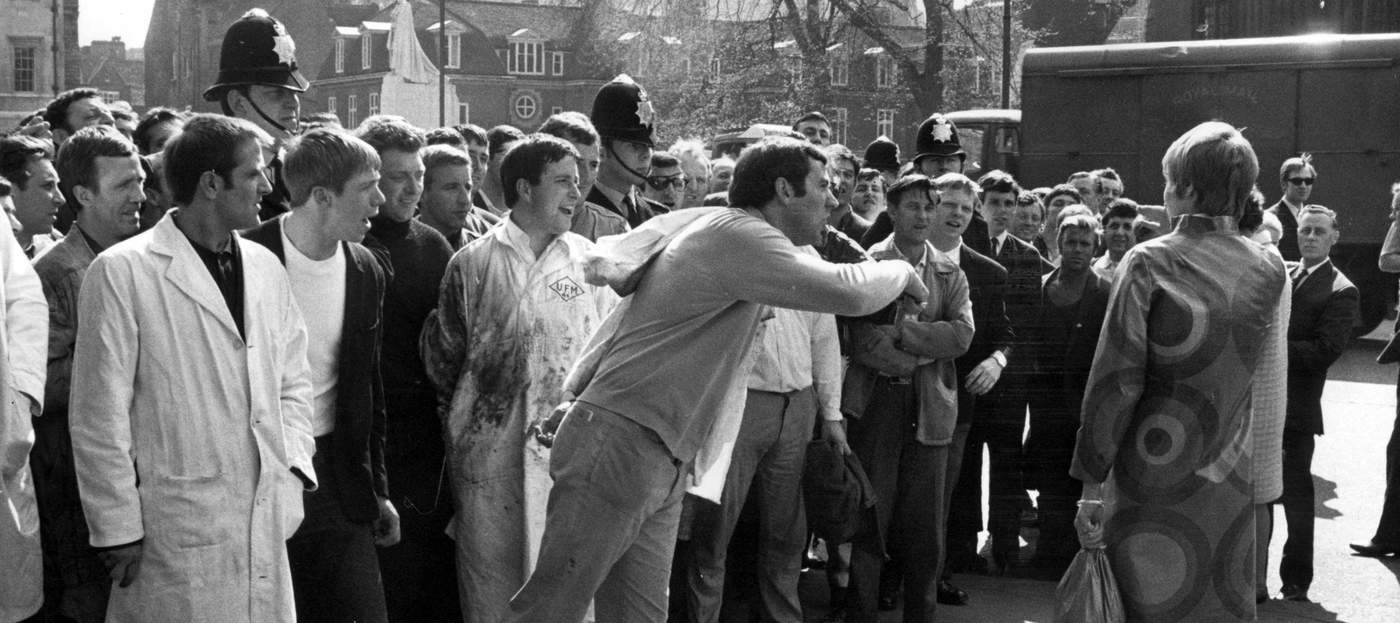

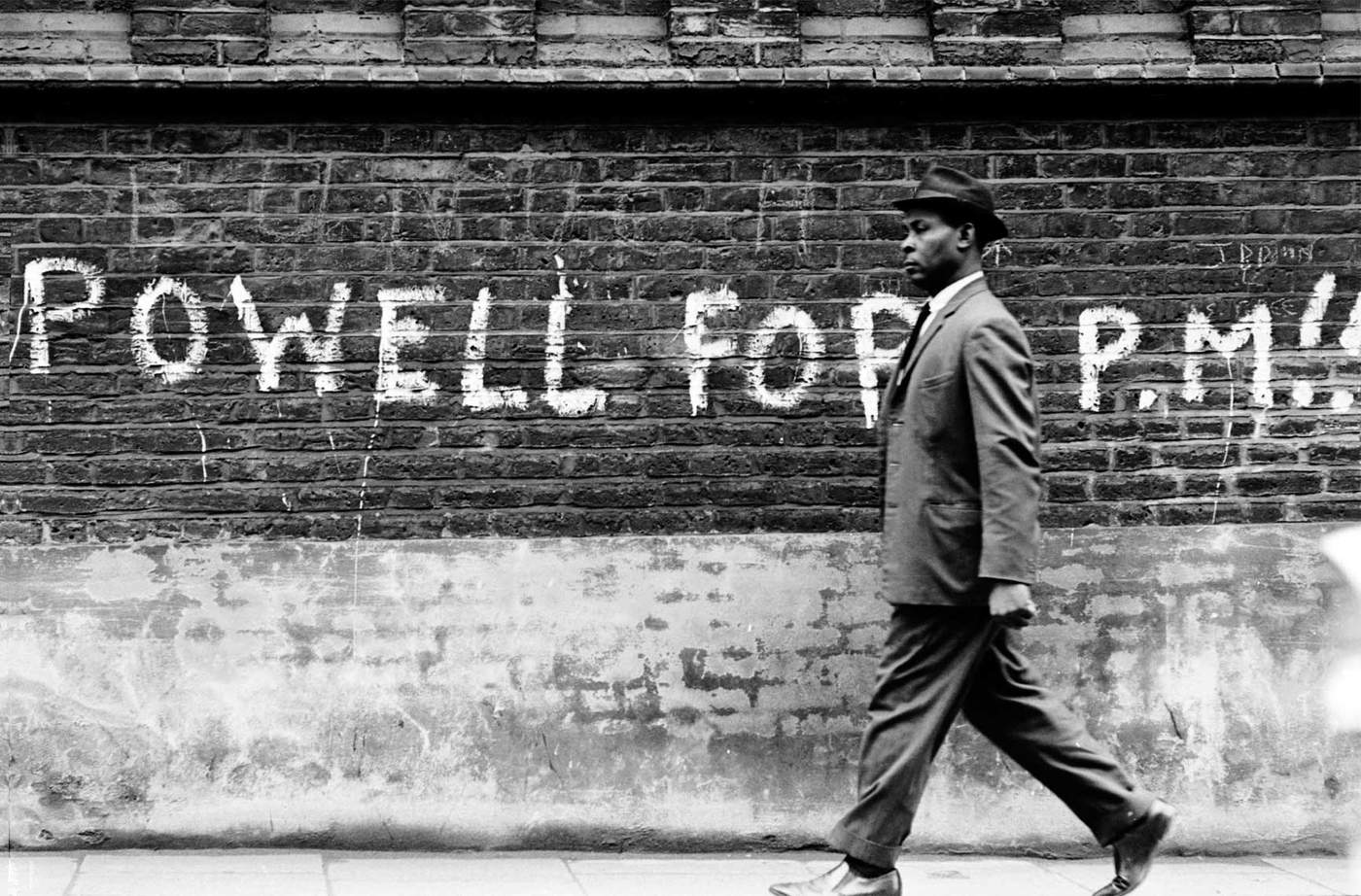

The impact of the speech was explosive.

Powell was sacked from the shadow cabinet by Edward Heath, although he received strong support from the public, with dockers and meat packers marching in support of him.

For the immigrant community, Powell's rhetoric - and the reaction to it - was terrifying.

The MP in Enoch Powell's old seat of Wolverhampton South West is currently Labour's Eleanor Smith - who became the West Midlands' first female black MP at the last election - and between 2010 and 2015 it was held for the Conservatives by Paul Uppal, a Sikh.

It was this community that was held up as an example by Powell of why immigration wouldn't work.

Eleanor Smith is the current MP for Wolverhampton South West

But it's that same community that has become "so integrated and conservative", according to Mr Sanghera.

"The Asian community have been in Wolverhampton for 50, 60, 70 years. They are a conservative community - they believe in education, they believe in family.

"I [also] think the West Indian community are quite conservative."

The way the city voted in 2016's EU referendum - 19 of its 20 wards backed Leave - was not surprising to Mr Sanghera.

"It’s human nature to worry about immigration, to worry resources are going to be taken by outsiders," he says.

"Every phase of immigrants is worried by the next phase of immigrants – that’s human nature."

Sathnam Sanghera went to Wolverhampton Grammar School

Five decades on from his speech, some of Powell's ideas have taken hold in mainstream politics, according to Dr Hirsch.

"The idea of 'immigration numbers' that simply need to be 'controlled' was once seen as an attack on people's rights," she says.

"It is now accepted within mainstream politics, and support for these immigration controls pushes ideas of nationalism and hierarchies of who is and isn't allowed into the country that are often connected with race."

Shirin Hirsch is writing a book about Powell

For Dr David Wearing, an academic at Royal Holloway, University of London, Powell's speech was a very early example of a modern phenomenon, what he describes as "a racist member of the elite hiding behind the white working class".

"Read the full text of Rivers of Blood and what strikes you is the sheer familiarity of it.

"Among other things, it falsely associates hostility to immigrants with the working classes alone, contrasting their supposedly legitimate concerns with those of an out-of-touch liberal elite."

David Wearing argues that Powell's speech gave legitimacy to racists

Dr Wearing adds: "Obviously Powell's speech was severely detrimental to the physical safety and wider well-being of people of colour in the UK, both immediately and for decades after he made it.

"It legitimised every racist beating, stabbing, arson attack, every denial of a job or housing, all the thousands of instances of these things that people endured up and down the country through the 70s, 80s and beyond."

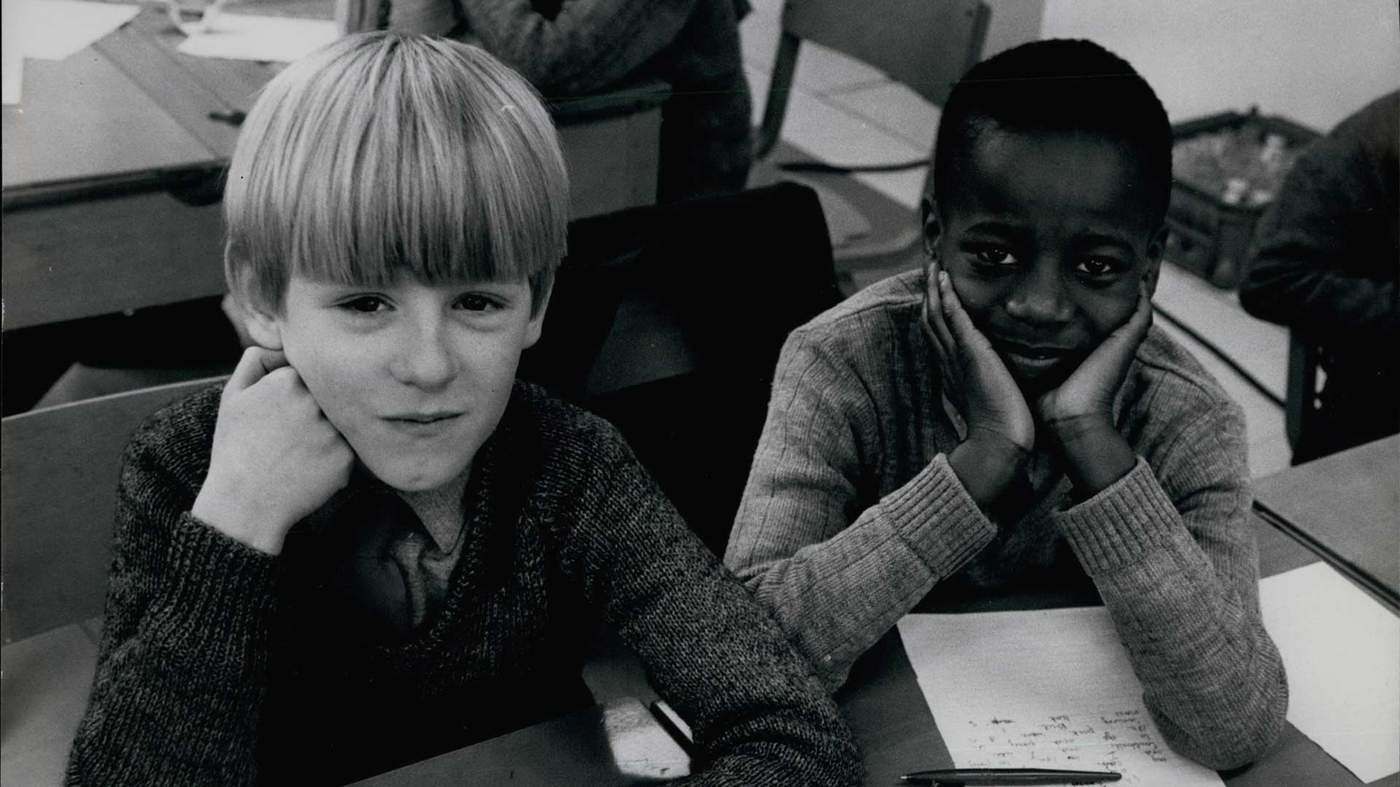

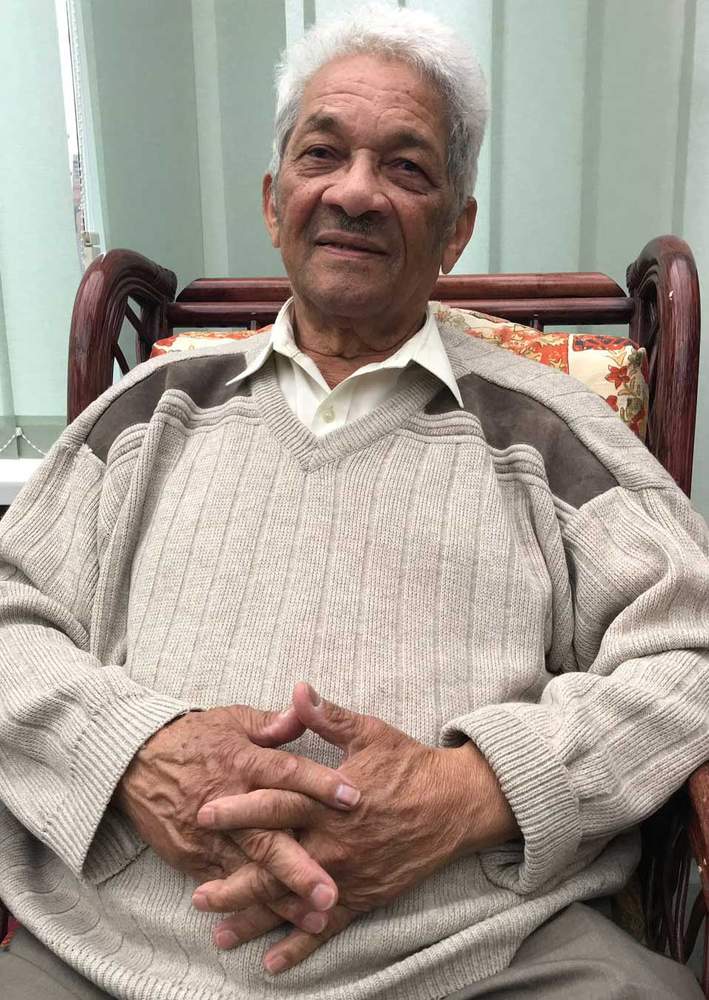

And what of the two little boys who were inadvertently thrust into the limelight by Powell?

"At one stage I said, 'should I be here?' I questioned myself at the age of around nine or 10 - 'why did my parents come here?'," says Mr Comrie.

"Even though I was born in this country I still felt like I was born in the wrong place.

"Even though it's multi-racial, I still feel I'm in the wrong place today."

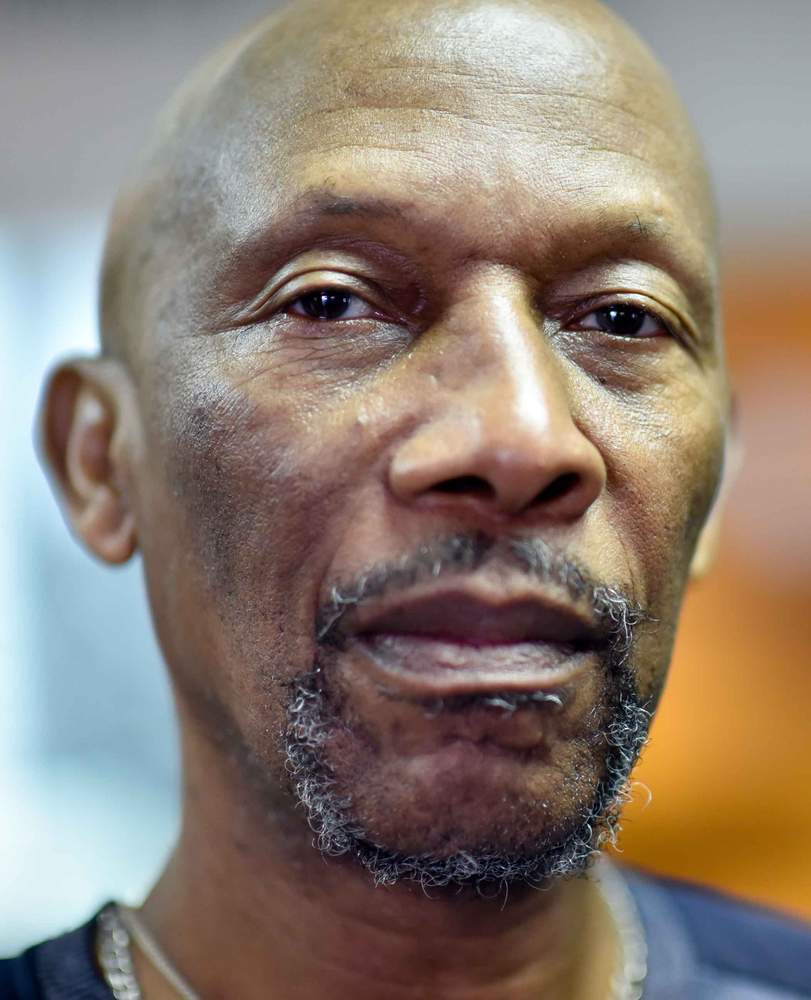

For Mr Edwards, Powell's speech helped to shape his life in a positive way.

Now a lecturer in union studies, he became a union rep at the age of 19.

Powell's former constituency office is now Wolverhampton's African Caribbean Heritage Centre

"Going back, I think I was politicised by where I was from: my family background, white working class, boat people living a slum.

"Going to West Park School and the Rivers of Blood speech - this is a part of it."

At a recent reunion of West Park's class of 1968, Mr Edwards says he contemplated the legacy of Powell's speech.

"It was calculated, intended to create division, and to some extent it worked," he says.

"This is the importance of our story today and the kids that went to that school.

"If you think about Britain today, it looks very different to how it did in 1968, and certainly going back to the reunion was just amazing because we all told our stories.

"We are Powell's legacy because we have won."