The Irish government announced the referendum date,

25 May, at the tail-end of March, signalling the start for campaigners – although many are no strangers to hitting the streets over abortion.

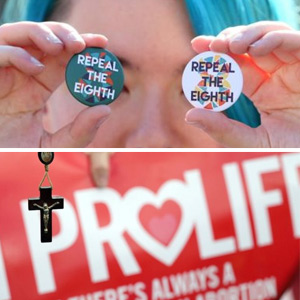

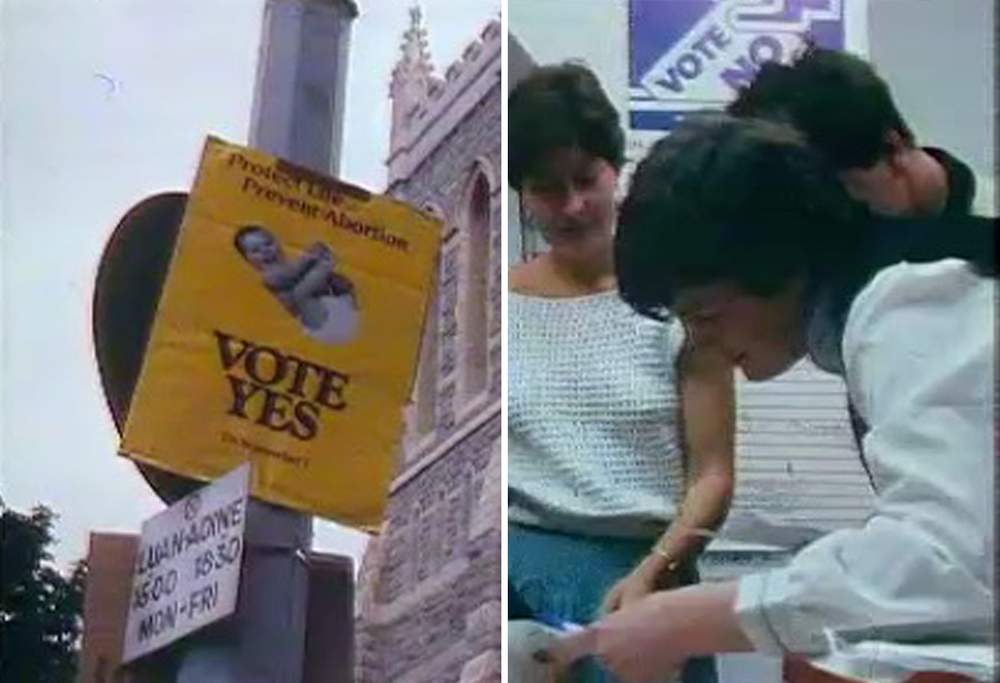

This is the sixth time Ireland has gone to the polls over its abortion laws since 1983, when the Eighth Amendment was added to the constitution.

Yes

The Yes campaign launched under the title Together For Yes, and has been bolstered by healthy early polling numbers and support from actors including Saoirse Ronan and Cillian Murphy.

The country's two largest parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, will allow their members to vote with their conscience.

Two smaller parties, Sinn Féin and the Labour Party, back repealing the Eighth Amendment.

Irish Prime Minister Fine Gael’s Leo Varadkar, and Fianna Fáil leader Micheál Martin are supporting a Yes vote.

No

The No campaigns, LoveBoth and Save the Eighth, have likewise been a highly visible presence on Ireland’s streets as the referendum day draws closer.

While polling numbers initially suggested a healthy lead for Yes, No supporters have been boosted in recent polls showing that the gap is closing.

And while Micheál Martin is supporting a Yes vote, a majority of his Fianna Fáil members of parliament and senators will be voting No.

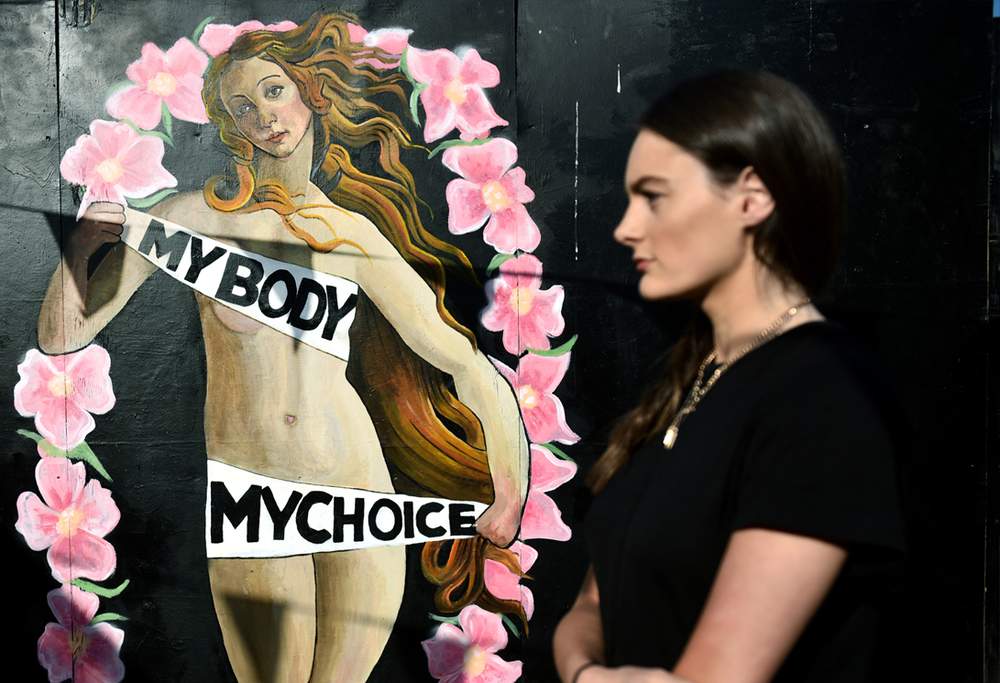

Lucy Moore is a full-time artist based in Dublin. Her mural of a pro-choice Venus at a Dublin pub, the George Bernard Shaw, has become one of the striking images in the final weeks of the Yes campaign.

The repeal movement means a lot to me and I wanted to contribute something.

I’m not very good with words, so I wouldn’t be good at canvassing or going door to door – painting is what I do.

The mural went up about three weeks ago - I was getting quite frustrated after watching a debate on televison.

So I emailed a few businesses, but it’s difficult because some people don’t really want to put a political mural on their business.

I guess this is my contribution to the campaign. I care a lot about the rights of women in Ireland.

Ireland needs to up its game in terms of women’s rights.

I really didn’t think the mural would have as much reach as it did. I thought it might not have that much impact, because I don’t think many people who would step into the Bernard Shaw will be voting No.

But I suppose Instagram is a good way of spreading it around, people have been taking photos of it while having a few drinks and I’ve seen it on a few news sites.

I was quite certain that we would be getting repeal going forward but I don’t know – I’m getting a bit scared now.

I would feel very happy and proud of Ireland if it was a Yes.

If you take it back to the marriage equality referendum, that was such a great day.

Obviously, there’s a very serious side to this, it’s not all joy – at the end of the day we are talking about abortions.

Katie Ascough is a No campaigner for the LoveBoth campaign.

Last year, she was impeached as University College Dublin student union president after a row about information on abortion being published in a student magazine.

She is due to graduate in September.

My mum had a miscarriage and I was asked if I wanted to meet my 13-week old brother.

I got to hold him in my hand and look into his face.

I was shocked.

He had a fully-formed body with arms and legs, fingers and toes.

He had a face with eyes, ears, nose and mouth. He had tiny fingernails and even creases on his knuckles.

I think it brought us a lot of healing, allowed us time to mourn and say goodbye.

I realised, in that moment, he and others like him deserved a right to life.

Another thing that strengthened my view was that I felt I needed to know what I was talking about when I discussed abortion, so I watched one online.

It was one of the most horrific, violent and inhumane procedures I’ve ever seen in my life.

We hear so much on the Yes side about care and compassion but I’d really like to challenge those words because I think they’re euphemisms for what we’re really talking about.

Women do deserve better but we haven’t been talking about anything other than abortion.

We need to be talking about financial support for mothers, better and more accessible care, perinatal hospice care for children with life-limiting conditions.

Adoption services haven’t been discussed in any great lengths. Irish women deserve better, but abortion is not the answer.

Young people know more than any other previous generation about the development of a child.

If more people would look at the evidence and be honest with themselves about what an abortion does, then a lot more young people would be vocal about voting No.

Everyone has the right to voice their concern.

I’d be sad for Ireland if it was Yes – Ireland can do better.

But I’m hopeful, and quietly confident, of a No.

In 2001, Gaye and Gerry Edwards, first child Joshua was diagnosed with anencephaly, a condition in which a portion of the brain or skull of an embryo does not develop.

Joshua was delivered at 22 weeks via induced labour in a hospital in Northern Ireland.

Gaye and Gerry are both campaigning for a Yes vote.

When the scan started, the midwife was very chatty. She showed us the heartbeat, the spine – then she moved up towards the head.

She wasn't seeing all that she should.

A consultant came and did the scan in complete silence.

She said the baby had anencephaly.

It didn't dawn on me what it meant.

I was still waiting for her to tell me how they were going to fix it.

She told me the baby wasn't going to survive.

I went home and got the computer out – I wanted to prove her wrong.

But I found out there was no “happy ever after”.

I was overwhelmed, devastated.

I had pictured our future, starting our family. It had been taken away from us.

We had a consultation with a geneticist in Belfast and then were referred to an obstetrician in the city.

He scanned us again and, for the first time, I was asked: “What do you want to do?”

I said that if there was no prospect of life, I didn't feel I could carry on.

Three days later, I was back for my appointment.

I took two tablets and tried to get some sleep.

The next day contractions started. He was stillborn.

The nurses asked if I wanted to see him, but I had seen the scan and knew the condition was catastrophic.

I didn't want that to be my memory of him. They took him, washed him, took his footprints.

The hospital chaplain, a Catholic priest, came and gave a little service.

Two weeks later we received a couriered delivery, a little box containing Joshua's ashes.

In the hospitals in Dublin, there were no options given apart from continuing – and that felt like judgement.

But the doctors and nurses in Belfast were reassuring that this was an awful, devastating thing to happen.

In Dublin, I was only told what would happen, that I'd carry forward and have ante-natal appointments.

But the thought of going into the waiting room and being with all those happy bumps at 30 weeks, 40, 42 weeks – I didn't see how I could carry on.

I got angry. This was around the time of the 2002 referendum.

I shared my story and there was a flurry of activity.

Then I fell away from it; I was bringing up babies and having a family.

In 2012, I saw someone speaking on television about fatal foetal abnormalities.

I was racked with guilt – if I had worked harder, had spoken up more, then maybe that wouldn't have happened to that other woman.

So from then, I've been hard at work campaigning.

Irish people are starting to see in great detail the damage done by the Eighth.

And I have great respect for people who choose to continue with pregnancy in a situation like mine.

But whatever a person decides should be supported.

If it does get changed, this will go back to being a private issue.

For us, it was more than just private – it was secret to have had an abortion.

Now, I'd like it to go back to just being private.

Caitríona Lynch is a grandmother and LoveBoth campaigner from Dún Laoghaire.

She spoke during a break from going door-to-door in south Dublin.

It's my second run campaigning for the Eighth Amendment.

The first time was in 1983.

I was part of the campaign to put the Eighth into the constitution.

Campaigning in 1983

For me, it's a matter of life and death.

I believe the unborn child is precisely that – a child.

I understand abortion to be the direct and intentional killing of an unborn child.

And I am a woman who has experienced a miscarriage and a number of my friends have had issues such as ectopic pregnancies.

We were never in any doubt about the care we received. And there are unavoidable cases where the baby dies.

But we never intended to kill the child and what we're looking at now is a procedure with that intention.

It comes down to one question for me – whether you believe that the life of an unborn child is just that, a human child.

If you do, then this is a horrendous act that needs to be opposed.

On the doors, people are genuinely wanting to engage. They want to know both sides of this.

I haven't had much contact with the Yes campaign, but I've engaged with any number of people on the doors and I haven't seen many people who are angry or rude.

Most are quite polite.

I get the sense there are less people voting my way than in 1983 (67% voted in favour of the Eighth Amendment in the 1983 referendum).

But I'm heartened by the sense that people see the unborn child as a child and they don't want to bring in unrestricted abortion.

I'd be very sad if there was a Yes vote. I'd see it as the end of an era and the beginning of a long, hard road to bring people back to an understanding of how sacred and precious unborn life is.

I agree that we should offer women something better than simply “kill your child”.

We should pursue options around allowing people to keep their baby or look at adoption services.

And I understand about the hard cases, they are awful. But they make up a tiny proportion.

Abortion is like taking a gun to your head to cure a headache.

I'm proud that we have this stance as a small country.

In some ways, we have led the world with legislation such as the smoking ban.

So why shouldn't we lead the world on something as serious as the life of an unborn child?

I'm quietly confident we'll get there. As long as lives are protected, that's what matters.

Then we can roll up our sleeves and get on with taking care of our pregnant women.

That's the thing – we believe we can take care of both.

Dr Cliona Murphy is an obstetrician and gynaecologist based in Dublin.

She is the incoming chair of the Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in Ireland and is supporting a Yes vote.

The current situation is not working for doctors and it's not working for women in Ireland.

I've had a number of cases where the woman's life is at risk during pregnancy.

You're trying to weigh up what is a “real and substantial” risk (as defined in the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013).

Real and substantial is not a medical term, you cannot quantify it.

For example, we frequently have patients where the waters rupture.

A miscarriage is inevitable; there is no hope for the life of the foetus. But when there's a heartbeat, it's difficult to intervene.

The correct action would be to expedite the miscarriage, which is what would happen in the UK or any other jurisdiction.

I’m also troubled by people who needed a termination for their health needs but did not qualify under the act.

That's very frustrating. I've found it unworkable.

The other main sticking point is the woman's viewpoint doesn't come into it.

In any other decision, the patient is part of the decision-making process.

Here, the woman doesn't get to put up her hand and say: “Actually, there's too much risk to my life to continue with this pregnancy, so I vote not to.”

That's just unacceptable.

I didn't start out to be an active member of the Yes campaign. I've never canvassed for anything in my life.

I suppose my views have changed over the years.

There was no choice but to go out and advocate for women.

If it's a Yes vote, there will have to be a process where we have the correct procedures and guidelines in our hospitals.

But it will take a weight off our shoulders as doctors and will be a relief for people going around with guilt and shame, who feel they can't tell their doctors they had a termination or feel ambivalent about a pregnancy.

We can talk openly about their choices.

Caroline Simons is a Dublin-based lawyer and legal adviser to the campaign for a No vote in the abortion referendum.

I accept that it’s sometime necessary to terminate pregnancies in order to save mothers’ lives.

I have survived complicated pregnancies. What is being proposed in legislation is termination of the baby and there’s no evidence that you need to terminate babies in order to address women's health issues.

If the constitutional protection for the unborn is removed, then any future legislation for protecting the unborn won’t endure against the constitutional rights holder – the mother – in any legal challenge.

That’s why a professor of constitutional law, Gerry Whyte, has said it will mean abortion on demand.

The only procedure envisaged in the government’s proposed legislation is a termination – but it’s actually defined in the legislation as a medical procedure intended to cause the death of the foetus.

So there’s no misunderstanding, no misapprehension – it couldn’t be more clear.

I’d be extremely upset if it was repealed.

I would feel that people have been frightened into voting for this because we’re talking non-stop in the media about very few cases, hard cases, like disability and rape.

If people want to put out a proposal for more abortion, on its own merits, as a service which society demands of medics, that’s one thing.

But to pretend that women are being denied healthcare to avoid risks to their life and frighten people into voting for it – I find that absolutely repugnant.

I don't know anybody who's been involved in the pro-life side of these debates who isn't also involved in voluntary work, in assisting women who are in these situations.

That's my reality.

For some medical conditions in other countries, they terminate the baby first and then they treat the mother.

Here, we don't do that and yet we have better outcomes in terms of mortality and morbidity. So I don't see the medical argument for abortion.

There may be a societal demand for it, but that's a different thing.

Una Mullally is a journalist and commentator. Andrea Horan is an activist and entrepreneur.

Together, they are the founders of the Don't Stop Repealin' podcast, which has interviewed Taoiseach Leo Varadkar amongst others in the lead up to this week's vote.

Una: We started the podcast because, personally, I was sick of those adversarial, binary broadcast debates.

From a journalistic point of view, I don't think they add that much to the conversation.

People just get frustrated and angry and Andrea was a natural go-to because of her activism.

Andrea: I've never done any broadcasting but there was no arm-twisting.

It was also good to have someone who wanted to talk back to me whereas my friends didn't – so I was like: "Finally, yes! I can actually talk about all of this!"

Una: What we do is irreverent, it's motivating but it's also quite serious.

We're getting tens of thousands of listeners and party leaders to speak to us.

So, yes, our logo is pink, we sing the theme tune but in many ways we're out-punching mainstream media.

Andrea: We're very for the people, of the people, by the people.

We're easy to listen to and bringing something that maybe has been out of reach to a lot of people who are not in the political or journalistic worlds.

Una: We provide an outlet for good humour and positivity that is much needed because these campaigns are so stressful.

The No campaign has been disgraceful, in many ways. I think their tactics online have been unethical, I think they have deliberately misled and spread misinformation.

And I don't say those things lightly. Some of that messaging has cut through, but I don't think the Irish electorate are big fans of the behaviour of the No campaign.

I think a lot of their messaging and imagery has turned a lot of people off. I have spoken to loads of undecided voters who are really offended by No camp posters.

Andrea: I think there's a worry that you don't change people's minds with facts, you change it with emotion.

And the No campaign has been heightened in emotion, unfairly, and that's a worry.

If it's a no vote, I don't know how the women of Ireland will cope. It'll feel like a punch in the face.

Una: Elections, referenda are always about something else.

This one, at the heart of it, is about personhood, how people are valued and cared for.

That's why the referendum is going to pass, because I think people really believe we need to take care of the women and girls of Ireland.

There are thousands of people out every night knocking on doors.

This is a massive rising of women and their allies. And you're not going to beat it.

Andrea: In my mind, I feel like I don't know how it's going to go.

But, when I step away, my heart says Yes. I can't see how repeal can't pass.

Tim Jackson is a 28-year-old from Ballybofey,

County Donegal, who is part of the Vote No Roadshow organised by the Save the 8th Campaign.

In the four weeks leading up to the referendum, the roadshow visited 100 towns and cities in the Republic's 26 counties.

I sometimes think about the first time I understood what the word abortion meant.

Myself and my mum were in a car and, for some reason, the topic came up.

I can't remember how or why but I just started imagining what abortion meant.

That there was some little person in the mother that was growing and I didn't know what to think about the idea of its life being ended.

I still vividly remember going through that dilemma and not knowing – being conflicted about it.

Almost 10 years ago, my friend asked me to come to a conference.

I was 19 and I had no strong opinions on abortion. But we were shown a video of an abortion and I could not believe my eyes.

It was from that point on it ceased to be a theoretical issue and started becoming something that didn't sit easily with me, thinking about how many lives were on the line, were lost and are still being lost.

I realised that it was the most important human rights issue of our time.

We’re in Dundalk after four weeks travelling with the roadshow.

We’ve been very encouraged by what we’ve seen on the ground.

We don't hold back from sharing the truth because the truth itself isn't palatable.

The tone we're taking is quite frank with people about the issue because people respect that kind of honesty.

They don't want to talk in politically diplomatic terms about issues of life and death.

That honesty is probably reflected in the posters as well.

The polls would suggest we have every chance in the referendum; we've been narrowing their lead all the time.

But it's hanging in the balance, without a doubt.