By Alastair Leithead

The Congo is one of the world’s great rivers.

It flows for 4,700km (2,920 miles) from the heart of Africa to the Atlantic Ocean through the second largest rainforest on the planet.

The Congo River drains the Democratic Republic of the Congo - a beautiful, resource-rich, but deeply troubled country the size of Western Europe.

Stunted by centuries of exploitation, what was once one of Africa’s richest countries is today one of its poorest.

But along the mighty river you can find precious resources and amazing wildlife found nowhere else on Earth.

Over millennia the outpouring of the Congo River has carved a deep trench in the sea floor up to a thousand metres deep - a submarine canyon which heads hundreds of kilometres out into the Atlantic Ocean.

If tamed, the Congo would have the potential to generate twice as much hydroelectric power as the world’s largest dam, the Three Gorges Dam in China, and to supply electricity across Africa.

The European explorers

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover the river in 1482 when they saw muddy water flowing far out to sea and followed it to shore.

They encountered the Kingdom of Kongo - a well-organised society open to outsiders and trading in slaves and ivory.

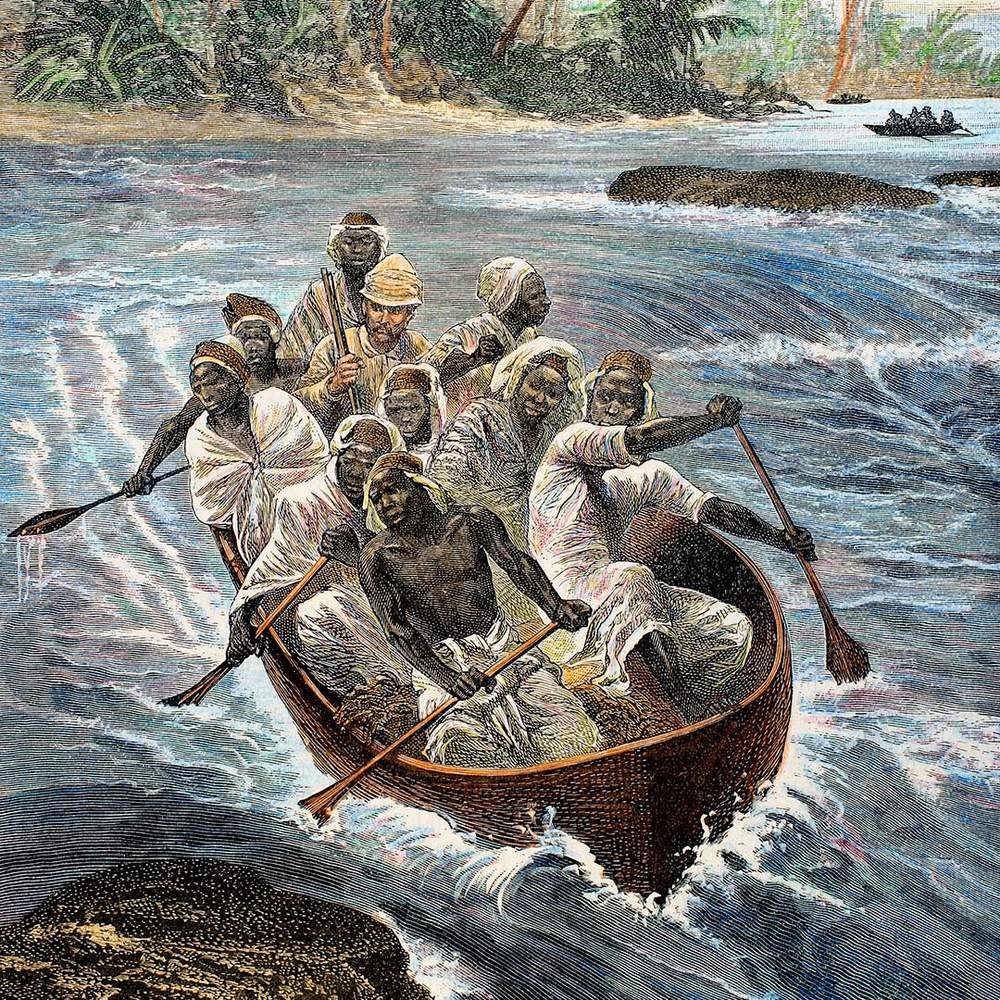

But just 100km (62 miles) upstream, a long stretch of fierce rapids makes the Congo impassable by boat, and it was centuries before the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley became the first European to travel the length of the river.

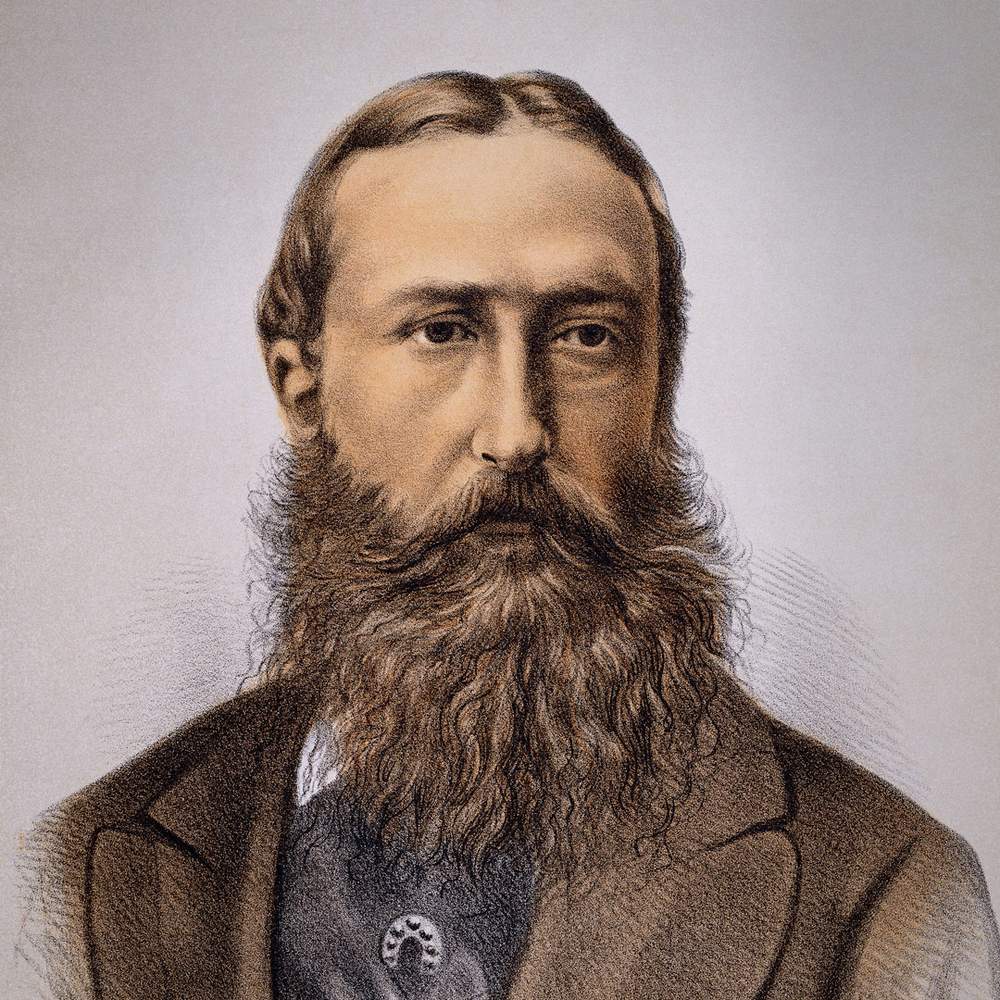

Henry Morton Stanley and, below,

navigating rapids on the Congo River

From the east coast of Africa it took him 999 days to reach the Atlantic on the west coast - and his arrival in the port of Boma in 1877 opened up the interior of Congo and changed it forever.

At a time of European expansion, King Leopold II of Belgium made it his own personal colony and employed Stanley to exploit its riches and build a railway around the rapids.

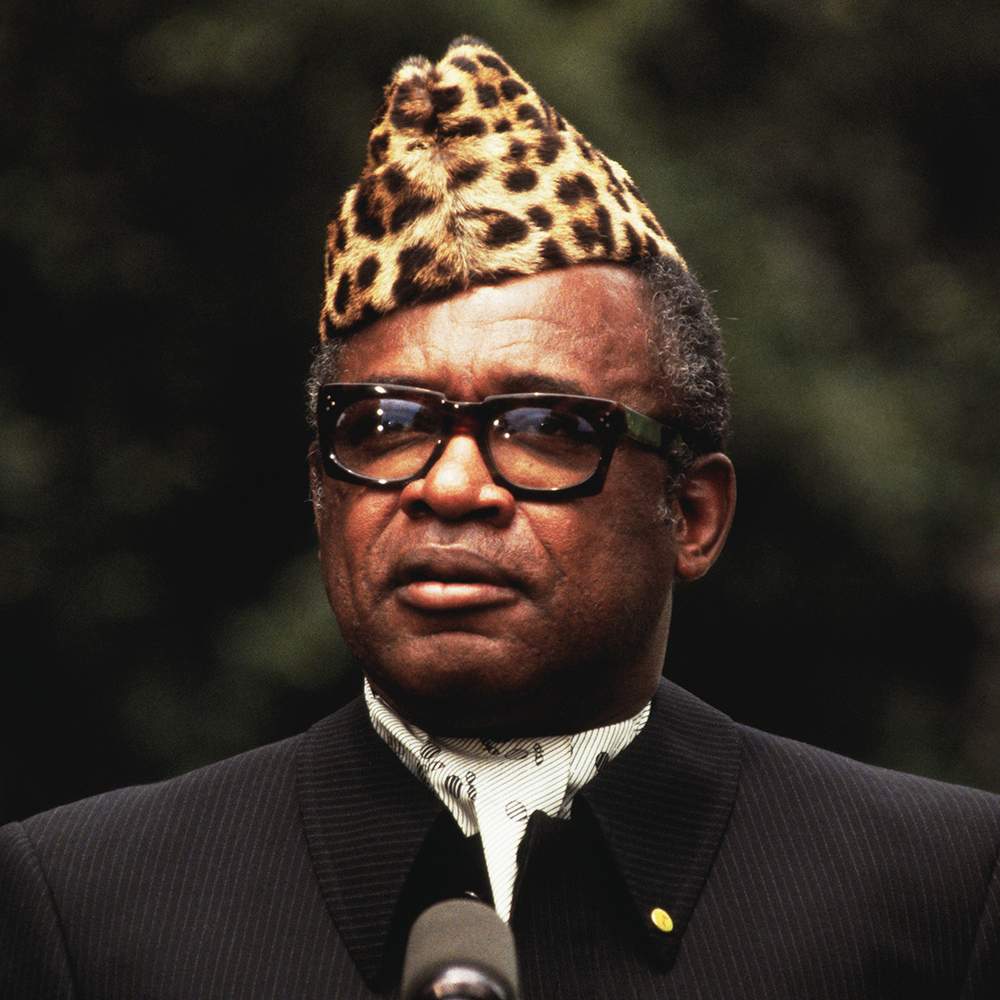

King Leopold II

Along the banks of the Congo River, some of the worst to suffer under King Leopold’s rule were the pygmy communities who were forced to collect rubber from wild forest vines.

The pygmies still hunt in the jungle for plants and animals.

Mobutu's rise and fall

The vast swathe of central Africa now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DR Congo) has been exploited for centuries - by the early European explorers, by Belgium and its cruel king, and then through the more recent greed of its Congolese leadership.

In 1960, the country that for decades had been the Belgian Congo gained its independence.

Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba (l) and Belgian Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens sign the act of independence, 1960

After elections, the first prime minister was Patrice Lumumba, but amid a struggle for political control of the country he turned to the Soviet Union for help.

The Cold War was at its height and both Belgium and the CIA interfered, backing the army chief Mobutu Sese Seko.

He handed Lumumba over to rebels who executed him, cut up his body and dissolved it in acid.

Mobutu Sese Seko (1984) and, below, signs in Lubumbashi: “Thank you citizen president. Mobutu Sese Seko our only hope.” (1979)

In 1965, Mobutu assumed the presidency after a bloodless coup and became a textbook dictator, dividing and persecuting his rivals - and through nepotism and corruption he enriched himself at the expense of the country, which he renamed Zaire.

In his remote home town of Gbadolite, he built a lavish palace and an airport to fly in luxuries like pink champagne. The runway was long enough to land Concorde - which he chartered.

But when he was ousted in 1997, time stopped in the remote town. The jungle has now reclaimed his palace.

Travelling the Congo

Infrastructure across DR Congo is crumbling - not just at Mobutu’s palace or in his home town.

In this country the size of Western Europe it’s incredibly difficult and expensive to get around.

Africa, with DR Congo marked red

The country’s only superhighway is the Congo River and even its vast network of tributaries is not used as much as it once was, or as it could be.

The river is navigable from the capital Kinshasa 1,600km (990 miles) upstream to Kisangani, and it’s the main route for transporting people and goods across the country.

There’s a real energy about life on the river - a place where people work, travel, live and trade.

Alastair Leithead's journey through the Democratic Republic of the Congo is also available as an interactive Virtual Reality experience.

A land of riches

DR Congo has vast resources - from the pristine rainforests to the valuable ores that lie beneath the soil.

It has gold, diamonds, uranium, rare-earth metals, copper and cobalt - an essential ingredient in electric car batteries.

The south-eastern province of Katanga is the centre of the country’s mining industry with vast areas of open-cast pits and 60% of the world’s cobalt reserves.

The shiny, brittle metal extracted from blueish-green ore is an essential stabiliser in batteries. It used to be a waste product of copper production, but its price has dramatically increased in the past few years.

It’s so much in demand that thousands of “artisanal mines” have sprung up - small, mostly illegal and unregulated pits where women and children often work in appalling conditions.

Artisanal miners sorting minerals

Well-connected families, military officers and local warlords make Katanga a Wild West of big money deals and corruption.

“Corruption is one of our challenges… a bad habit we have inherited when we got independence,” says Lambert Mende Omalanga, minister of communications and government spokesman for DR Congo.

“We can’t say that we have won, but still we are trying to stop it because we can’t maintain being a very rich country with a very poor people.”

The gorillas

The drive to extract resources from the ground is in conflict with protection of the dense forests - home to a species found only in DR Congo, the critically endangered eastern lowland gorillas.

Use your mouse, trackpad or arrow buttons to look left, right, up and down in this 360 video.

It will not work in some web browsers - and is best experienced on the YouTube mobile app.

The troubled east

War has ravaged the east of the country for the past 20 years. Five million people have died as a result of conflict.

It began when Rwandan troops pursued those involved in the 1994 genocide over the border.

With designs on the DR Congo’s mineral wealth - and allied with Uganda - they helped overthrow President Mobutu.

But it wasn’t long before the successor they had backed - Laurent Kabila - rejected the continued presence of foreign troops in the country.

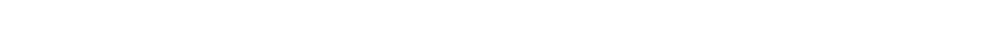

Laurent Kabila (1997)

Efforts to remove him sparked what some call the Great War of Africa, which at its height sucked in nine countries.

Cross-border militia groups grew and splintered, local strongmen armed their supporters and the fighting continues to this day as Kinshasa struggles to control the eastern edge of the country.

At the moment the epicentre is Beni in North Kivu province, where a group of rebels is killing civilians, soldiers and UN peacekeepers - and also allowing the Ebola virus to spread out of control.

Today's politics

The dominating face of Congolese politics for the past 17 years has been Joseph Kabila who took over as president when his father was assassinated by his bodyguard in 2001.

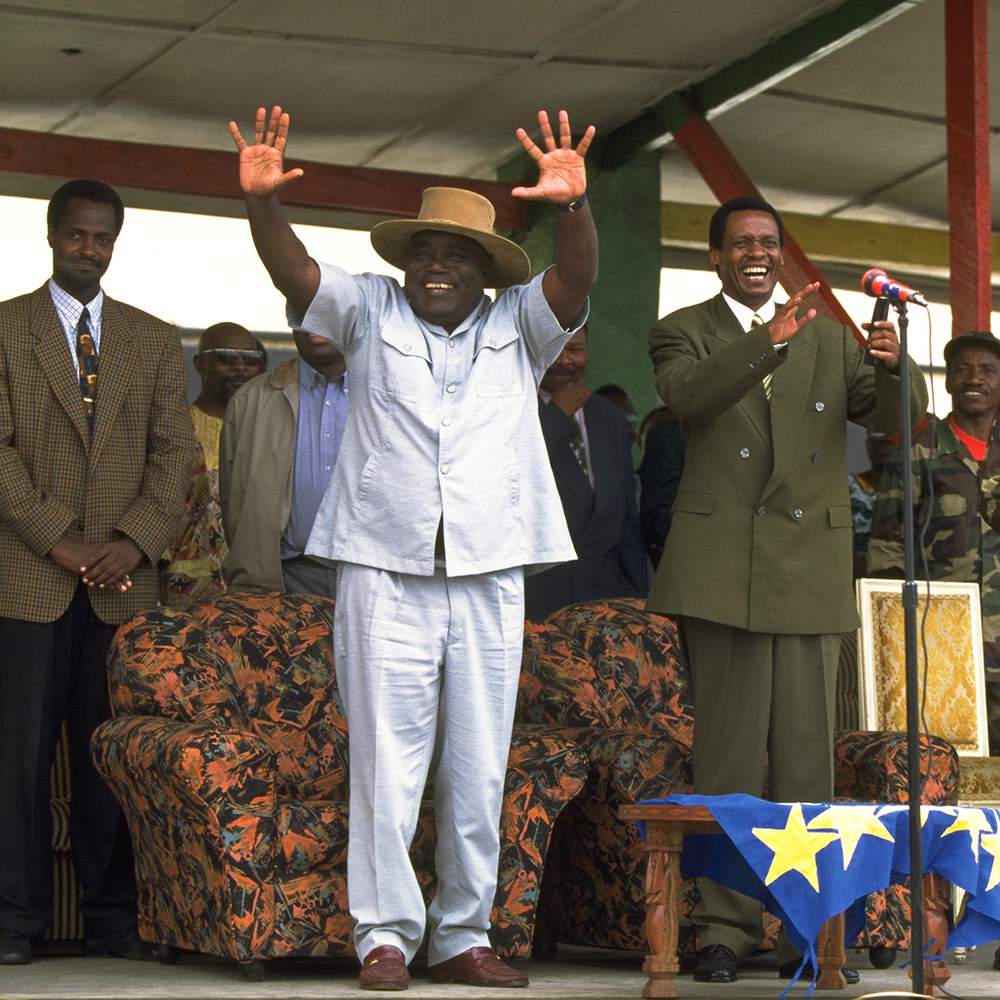

Joseph Kabila

Elections were delayed two years ago, but they’re now going ahead without him on the ballot paper - so they should bring change to the country’s leadership.

The opposition is galvanising around two candidates and Kabila has his choice. And while there has been controversy over electronic voting machines, now the country will decide.

Here’s a look at some of the key political issues in the DR Congo.

The future

DR Congo is a vast and beautiful country which has been held back by its history and kept down by corruption.

Its colonial rule was brutal and repressive, and its post-independence leadership was based around enriching the few at the cost of the many.

Since the fall of its defining dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, in 1997 it has been plagued by war and a continued instability that can suddenly spark into conflict that forces millions from their homes.

Militant groups and local strongmen use ethnic divisions for political gain.

It is also incredibly poor - the UN says at least 13 million people out of a population of more than 85 million need some form of assistance and many live in absolute poverty.

But it is young and energetic - two-thirds of the country are aged under 25. They have hopes and ambitions and are waiting for opportunities.

The current president has been accused of making his family rich on the country’s resources and of trying to hang on to power - allegations he denies.

But now that he has agreed to step aside, an election is being held and the people will vote.

Change is coming and with it DR Congo has the chance to transform itself into the beating heart of Africa.