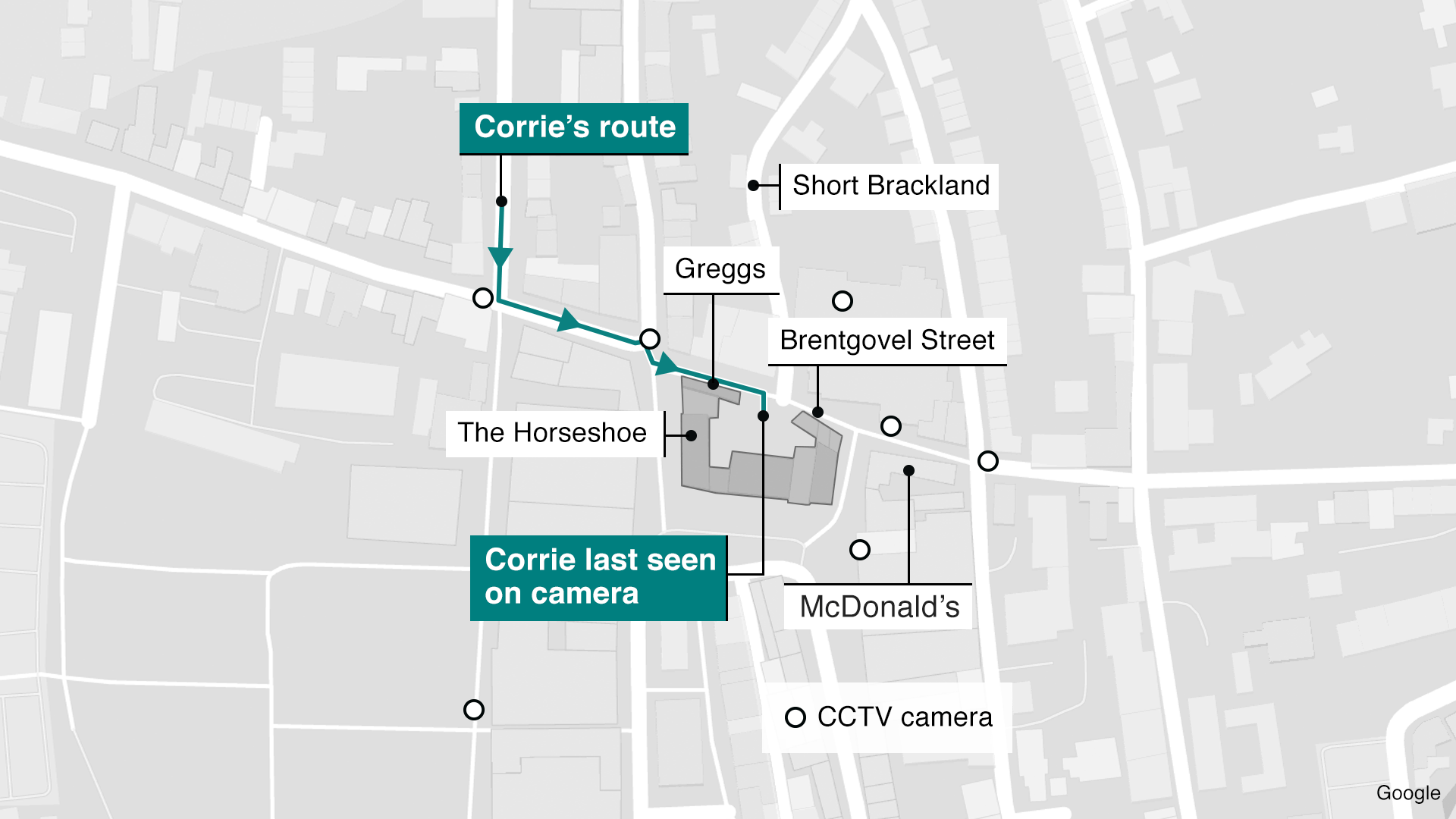

Corrie Mckeague's last known journey was recorded by CCTV.

The footage shows him alone, in the early hours of the morning, after a night out drinking last September.

Clutching a takeaway, he walks and sometimes staggers through the near-deserted streets of Bury St Edmunds, in Suffolk.

The time is 01:20 BST. He has become separated from his friends after being thrown out of a nightclub. Soon he will sleep for an hour in a shop doorway.

At 03:25, he appears again in front of the cameras in Brentgovel Street.

He pauses, before disappearing from view into an area known as the Horseshoe.

He has not been seen since.

Almost a year on, an enormous police search and social media campaign has found no trace of him.

Officers have spent months searching a landfill site for his remains without success.

His girlfriend has given birth to their baby daughter.

His family fear he is dead but remain haunted by unanswered questions about how he died.

According to his mother, the 23-year-old RAF airman was a risk-taker whose approach to life was shaped by a shocking experience in his childhood.

Did this play a role in his disappearance?

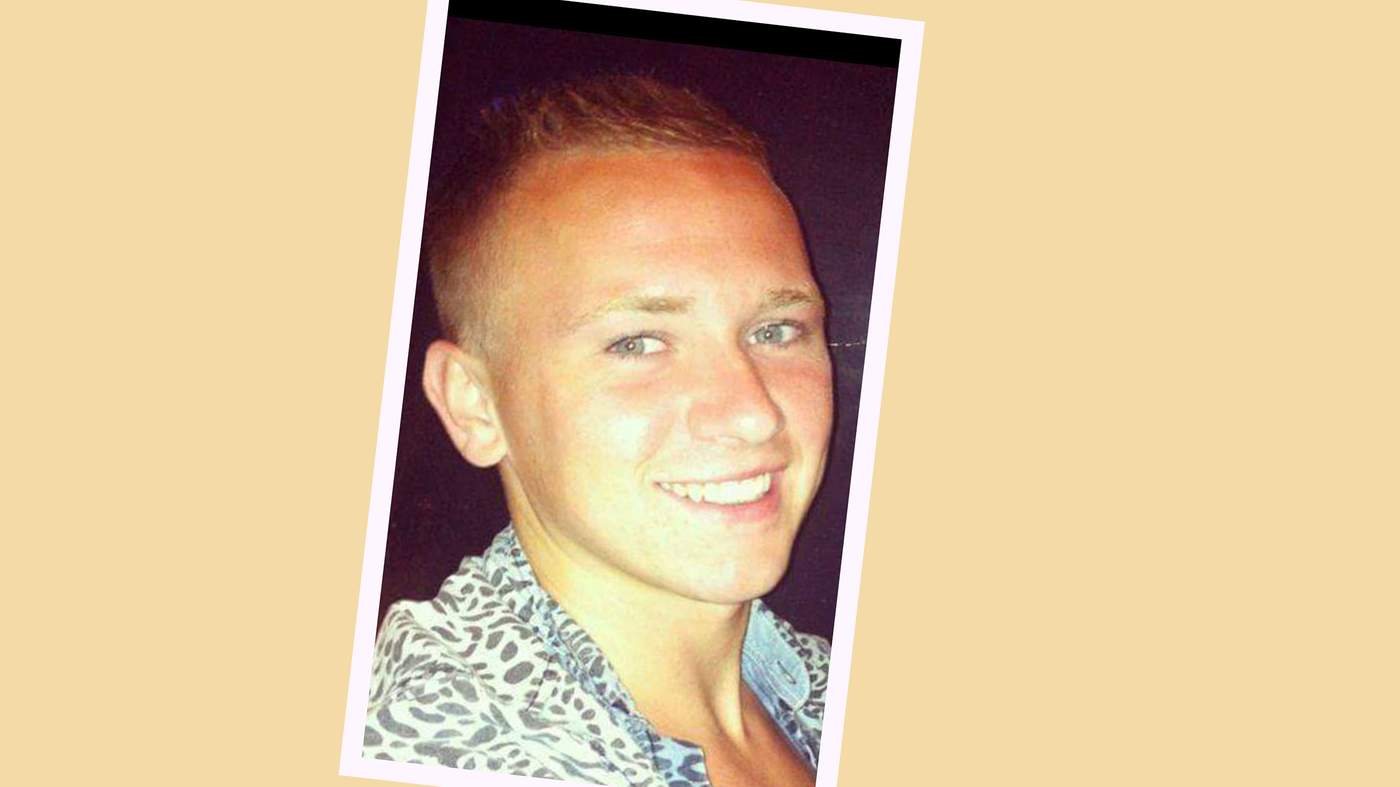

Corrie was a confident young man, popular with the opposite sex. With his good looks and Scottish accent he stood out from the crowd.

Even the way he dressed reflected his outgoing nature. On the night he disappeared he was wearing a pink shirt and white trousers, a look that caught the eye in a small town like Bury St Edmunds.

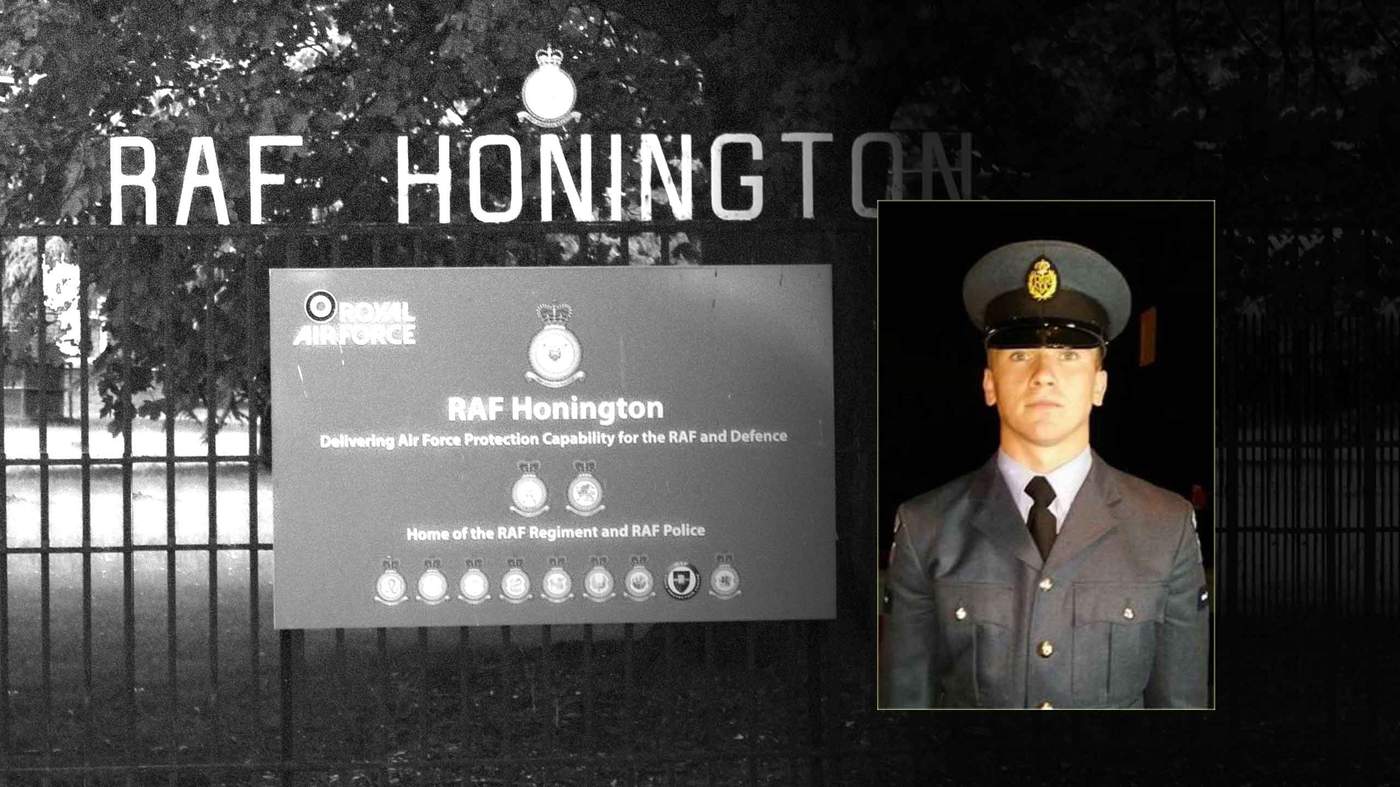

He and his friends from RAF Honington - an airbase 10 miles away - were regulars in Bury’s bars and clubs. On 23 September 2016 they had planned a typical night out.

However, there had been a mix up. Two of Corrie’s friends had each thought he was getting a lift with the other - and as a result he was left behind.

Undeterred, he drove his BMW into town. Once parked, just after 22:00, he spoke to his younger brother Darroch on the phone for 45 minutes while drinking a bottle of rosé wine.

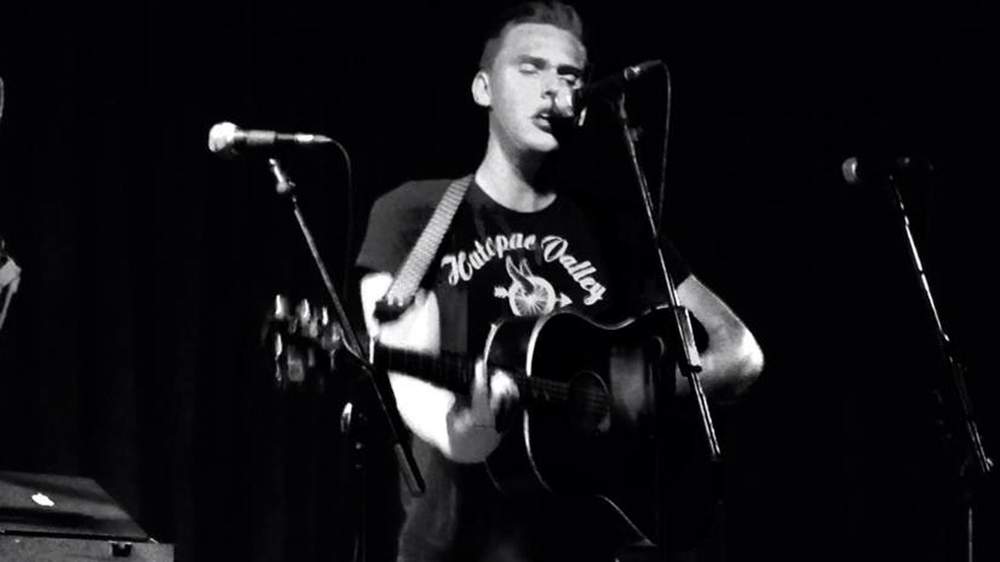

Finally, he caught up with his mates at So Bar. Here, local musician Nick Lowe was playing his normal mix of covers.

Corrie was not content to merely listen. Instead he went up to him and asked him to play the 1940s hit "Chattanooga Choo Choo" while he sang along.

Musician Nick Lowe performed an impromptu duet with Corrie in So Bar

"He knew all the words, which surprised me," he said.

"When we finished, there was the pitter patter of applause, and I was a bit like ‘what the hell was that?’ It was all very random."

The group then hurried on to Wetherspoon's at about 23:30.

Once inside the grandiose former Corn Exchange, Corrie moved around, greeting and hugging people he knew.

"He was coming up to loads of different tables, saying 'hello' to everyone," said Megan Manning, who was in the bar that night.

"He was chatty, he was nice."

Bouncer James Dilnot, who knew Corrie as a regular, said he was "happy, bubbly, bouncing about - his normal self".

"Through the night he came outside for a cigarette two or three times, had a conversation with me each time and gave me a hug.

"When he left he was intoxicated but he was able and capable of knowing what he was doing, where he was going, who he was with."

The door staff at the next venue were less happy about Corrie.

As his group arrived at Flex nightclub at about 00:30, he stumbled through the door, before slurring an "I love you" to the manager.

About 30 minutes later, he stumbled again while walking past a doorman, who tapped him on the shoulder and firmly told him to leave.

Corrie held his hands up before walking back outside. It was just after 01:00.

He walked down the street towards his favourite takeaway, Pizza Mama Mia.

Here he ordered a huge dinner - two burgers, a kebab and some chips.

Collecting his food, he walked a short distance around the corner, before sitting in front of Hughes electrical store to eat.

Soon, slumped in the doorway, he was sound asleep.

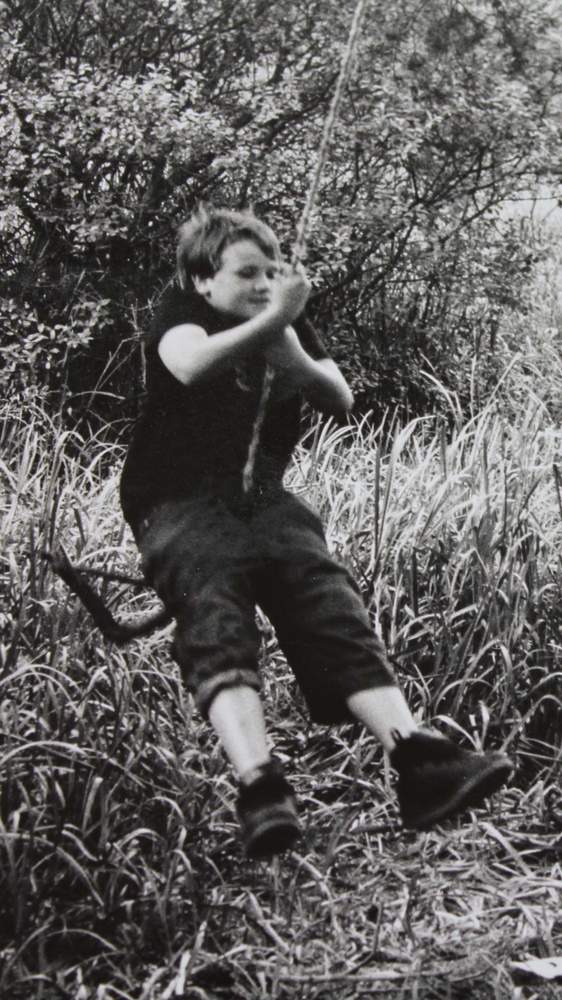

The "heaven stones", as Corrie and his two brothers used to call them, were dotted between the ruins of the thick cathedral walls.

They stand alongside the soaring towers and arches of the medieval St Andrew’s cathedral, which overlooks the North Sea on the east coast of Scotland.

As boys, the brothers loved to play among them.

They would study the weather-battered names and dates of each lopsided gravestone, imagining the lives of the people buried below.

Behind them, an elderly couple would follow close by. Their grandparents, Oliver and Mary, brought them here most weekends. It had become a bit of a ritual.

The Mckeague brothers: Darroch, Corrie and Makeyan

"They were always very good with us," recalled Mary.

"We used to take them to the chapel for mass, and then I’d give them the choice of what they wanted to do.

"They always wanted to go for a picnic, and it was always through to St Andrews to the old cathedral."

There were just a couple of years in age between each of the Mckeague brothers - Makeyan, Corrie and Darroch.

They lived with their mother and father in the small Fife town of Cupar, a place where most people knew each other, a place surrounded by rolling hills and green fields.

The boys made full use of their proximity to the countryside, spending days on their bikes, messing about in a stream or building dens with friends.

Corrie and Darroch - the two younger boys - were particularly close. They looked alike and were sometimes mistaken for twins.

All three enjoyed the macaroni and cheese their grandmother would make for them, or watching The Simpsons on TV.

Their home was full of pets - a dog called Homer and a rat called Stuart Little among their number - and it was a short walk to the primary school the boys attended.

However, their happy childhood was not to last.

Their parents, Nicola and Martin, divorced and the family was split apart. The boys and their mother moved 30 miles away to Dunfermline.

Aged 11, Corrie was hit particularly hard.

Corrie's grandmother Mary said Corrie was very upset by his parents' divorce

"The break-up of the marriage affected all three of them, but Corrie most of all," his grandmother said.

"He couldn’t handle it. He manipulated other people to get what he wanted. It seemed like he needed a little bit more help than the other two."

Academically, he struggled. There was a delay in diagnosing his dyslexia and he left school aged 16 with few qualifications.

Then, in the summer holidays that followed, Corrie experienced a devastating trauma.

It was early August, and he had been invited to a friend’s birthday party in Springfield, a few miles from Cupar.

Things got out of hand and police were called, his mother Nicola Urquhart said.

The group decided to continue the party in nearby woods where they would not disturb anyone. The woods were the other side of a railway track.

Natalie Mulholland, with whom Corrie had been friends since primary school, was with the group.

As they approached a level crossing, a train hurtled past at 70mph. The group heard a bang.

Corrie told his friends to stay back. He walked down the track and saw Natalie had been struck.

He found her phone, shoe and then her body.

"That changed him so much," Nicola said.

"He really did then have the attitude of ‘I won’t waste my life. If I want to do something fun, I will do it. I will take chances because you don’t know what’s around the corner tomorrow'."

It was an outlook that would shape the rest of his life.

Nicola was working out at the gym in Dunfermline when she got the phone call from her youngest son, Darroch. Corrie was missing.

It was Monday and no-one had seen or heard from him since the night out in Bury St Edmunds.

Her job as a family liaison officer for Police Scotland meant she was adept at detaching herself from the emotion of a situation.

But she felt uneasy. Her maternal instincts told her something was wrong.

Corrie's eight-month-old puppy, Louell, had been shut in his room at RAF Honington. Corrie wouldn't have left him alone.

Corrie hadn’t spoken to her, or his brothers, or anyone else from home over the weekend. That was also out of character.

Corrie had left his puppy Louell in his room before going out

Corrie had joined the RAF aged 19. It had turned his life around.

There had been many occasions when his family feared he would never settle down.

At 17, he had moved out of the family home into a flat in Dunfermline, where he lived with his older brother Makeyan.

The boys would often go on nights out in the town centre.

Lourenzos was one of the Dunfermline bars the brothers frequented

"If you asked me what Corrie liked? Corrie liked to party. He was the life and soul," said his father Martin.

"He was partying too much, to be honest with you, out in Dunfermline and in the flat."

Corrie dropped out of college, where he was training to be a hairdresser, and moved back in with his mum.

He fell into a series of jobs: Working in a clothes shop, at a call centre and as a fitness instructor.

His family was relieved when he announced he would follow in his maternal grandfather's footsteps and join the RAF.

However, Corrie found it hard and the RAF threatened to throw him out.

"I remember a phone call with him and he said ‘what am I going to do, Dad?’

"At that time he was out of control, and wasn't sticking to anything, partying all the time. He was never in trouble with the police, but was going out and drinking.

"I said if you want to stay, you have to try - and he did."

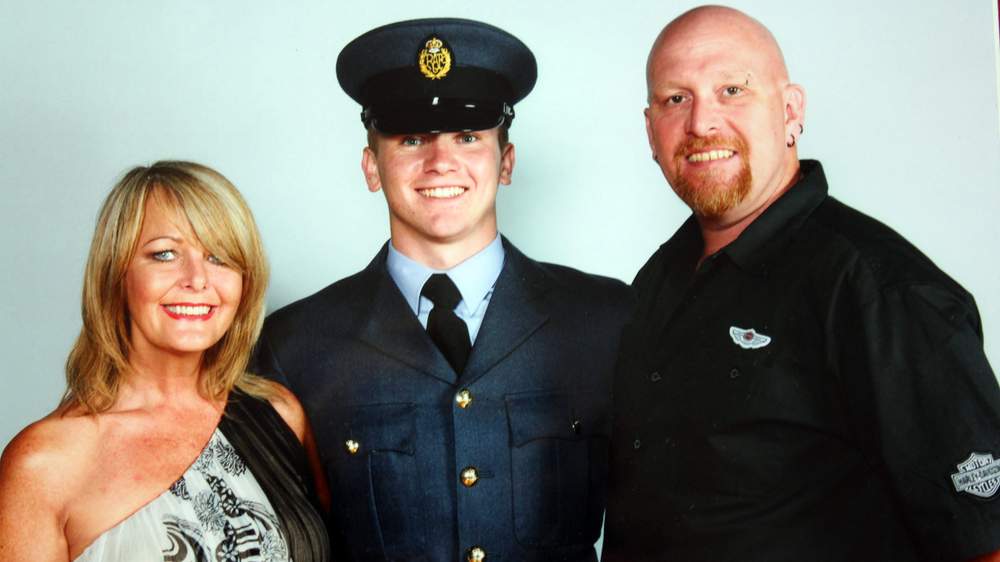

This photograph hangs in the living room of Martin McKeague’s bungalow in Cupar, in a spot where everyone coming through the door can see it.

On the day of his passing out ceremony, Corrie's family was

reunited for the first time in years.

After years of fractious relations and tension, both of his parents were there to celebrate his success.

"For Corrie, that was a proud moment," his stepmother Trisha recalled.

"He told us he got his mum and dad speaking again.

"He wanted to change his life and turn it around for everyone - and he did. It was amazing. It was something else."

It had seemed the young man’s life was finally on track.

So what had gone wrong? Where was Corrie?

After receiving that phone call from her youngest son, Nicola remembered something she’d heard on the news.

I knew something was wrong."

There had been an attempted abduction of a serviceman at RAF Marham in Norfolk, about 30 miles away from Corrie’s base at Honington.

At the time, police had said they could not discount terrorism as a motive. Nicola telephoned the guard’s office at RAF Honington.

The police were already there, trying to establish Corrie’s last known movements.

"I knew something was wrong, but I also knew [there was] only so much I could do," she said.

"I knew they needed information, bank details, phone details, all of that. I know what police officers do when they start to search, and that there was nothing I could do by running down there."

A few days later, and her son still had not turned up. Nicola and Darroch decided to travel down to Suffolk.

Martin and Trisha also made the long trip by car, and all four arrived in Bury almost exactly a week after Corrie had last been seen.

Their destination was the Horseshoe - the bin loading bay CCTV had recorded Corrie walking into.

It had been described to them by officers on the phone but they felt they had to see it with their own eyes.

Standing in the middle of a semicircle of the shabby backs of buildings, Nicola wondered: What could have happened to Corrie in this place?

And how had he managed to leave it unseen?

The Horseshoe is an unappealing place. An open space, surrounded by the backs of shops, with litter strewn on the floor and cigarette ends clustered in saucers left by workers.

Large red and blue bins are lined up on one side, overflowing with sacks of waste, juice cartons, scraps of paper and rotting bits of food.

It has a reputation as a haunt for drug users.

There are no CCTV cameras on the high walls of the buildings surrounding the bins.

Unless someone walks past, it is not monitored. In theory, it is impossible to leave the Horseshoe without being picked up by the cameras on the surrounding streets.

Short Brackland, Brentgovel Street and the road towards McDonald's are all covered by CCTV.

Corrie's movements on Friday and into the early hours of Saturday were captured, but the trail went cold when he walked into the Horseshoe at 03:25.

The only hint of where he was came from his mobile phone signal.

It was picked up in the early hours of Saturday where it was to be expected - in Bury town centre.

But at 08:00 it was 12 miles away, in Barton Mills.

Soon police realised the movements of the phone matched those of a bin lorry which had been to the Horseshoe not long after Corrie was last seen and travelled to a landfill site.

It seemed the obvious explanation. Corrie had somehow either got into the lorry or been put there and then travelled to the landfill site.

Corrie would take risks that other people wouldn’t."

Police later said he had previously been known to sleep in rubbish after a night out.

But his mother disputes that he would have tried to sleep in a bin. She points to his pride in his appearance and the fact he could have easily slept in his car, which was only a short walk away.

Talking in general about his character, though, she admits he could be reckless and would not always think of the consequences of his actions.

"Corrie would take risks that other people wouldn’t because he truly believed that he could handle himself," she said.

"I have never tried to paint that boy as a saint," she added.

"If anything was going to go wrong with any of my boys it was always going to be to him.

"If anyone was going to be in trouble it was always going to be him.

"If anyone was going to have drama, it was always him.

"He is absolutely adored by everybody – every girl he meets falls in love with him, every bloke he meets just thinks he’s the funniest person going."

Many people have questioned why the waste site was not searched earlier.

Weight data from the bin lorry indicated it had carried a load of about 11kg - far too light to have included Corrie.

As a result, police decided not to search the landfill site.

"You've got a situation where the weight was the only blocking fact to the logical explanation," said Colin Sutton, a former detective with the Metropolitan Police.

"They knew he went into the Horseshoe at a certain time, they knew his phone followed the route of the bin lorry - the only thing that prevented that hypothesis was the weight."

However, although Corrie's mobile phone was moving at a similar pace to the bin lorry, police believed his body would have been detected long before it reached the landfill.

"The strongest line of inquiry at that time was that Corrie had tried to walk home," said Det Supt Kate Elliott, of Suffolk Police.

Was not searching the landfill site the right decision?

It was now December. In a misty woodland near RAF Honington, the dull light was beginning to fade. Nicola was using a long stick to search through the undergrowth for any signs of her son.

Witnesses had told police after Corrie left the nightclub he had told them he planned to walk the 10 miles back to RAF Honington.

To cover as wide an area as possible, Nicola and other members of the public had been allowed to join the official search.

Supporters calling themselves "Corrie's Army" used Facebook and Twitter to spread awareness of the case all over the world and keep the story in the public eye.

One Facebook post, next to a photograph of Nicola searching through woodland, read: "This mum is searching forest undergrowth for her child. Her baby boy. Though an adult, he's her baby still.... It could be one of us parents looking for our child instead.

This photo of Nicola searching through woodland was shared worldwide

"You'd want everyone to help in ANY way. A tweet. A share. A pound. This photo could be you."

The post was shared almost 270,000 times and resonated around the world.

Nicola made an emotional appearance on ITV’s This Morning in early January for anyone who might have seen or heard from Corrie to come forward.

Media attention ratcheted up another notch when, on 9 January, a 21-year-old fitness instructor called April Oliver revealed she was pregnant with Corrie's child.

April Oliver later gave birth to a baby daughter

She and Nicola told reporters she had not found out about the baby until mid-October, two weeks after Corrie went missing.

Suddenly, pictures of the good-looking couple were splashed across newspapers and websites.

Further revelations about Corrie’s sex life were to come, including the couple’s membership of an online swinging site.

Soon questions were even being asked about the case in Parliament.

The #FindCorrie hashtag was already trending on social media and the family were being overwhelmed by the amount of information pouring in.

After a crowdfunding campaign, a private company was brought in to trawl through it all before passing anything relevant on to police.

But the physical searching and scouring of social media failed to turn up any significant new evidence. Theories were raised and discounted.

People recorded on CCTV in Bury on the night Corrie went missing were traced and spoken to, but provided nothing in the way of clues.

Suffolk Police - one of the smallest forces in the country - was coming under increasing pressure.

The investigation had only ever managed to establish one thing: The movement of Corrie’s phone matching those of a bin lorry.

But the weight data appeared to make the landfill an unlikely place for Corrie to have ended up.

The discovery of a major error in the bin weight data changed all that.

The artificial scent of bubblegum was being pumped out over the landfill site to disguise the stench of decomposition.

Eight police officers, dressed in white boiler suits and masks, were poking through the rubbish. They were looking for a clue, any clue, as to what happened to Corrie Mckeague.

It had emerged the bin lorry that had travelled from the Horseshoe to the landfill site had a load of more than 100kg, rather than 11kg as first thought.

It was therefore possible Corrie had been inside.

A 26-year-old Biffa employee was arrested in March on suspicion of perverting the course of justice but was later released without charge. It seemed the data error had been accidental.

For Corrie’s loved ones, the discovery was a devastating blow.

Any last hope he might have gone absent without leave, or chosen to hide away somewhere, seemed to have been extinguished.

Their torment grew as the search dragged on for months.

Corrie's mother and brothers could not face visiting the landfill site, but his father regularly travelled down from Cupar to be near the search.

"With every lift of the bucket - the jaws of the excavator - there’s every chance Corrie could be lifted in that," he said.

However, on 21 July, after more than four months, the search was finally called off.

Within days, 25,000 people had signed a petition calling for the search to be resumed.

Corrie's father even went to the lengths of blockading it with his motorhome, hoping to persuade police to change their mind.

Police insisted the decision to call the search off was not due to the cost, which was more than £1.2m.

They said they had exhausted the area where Corrie's body was most likely to be - but there was no evidence to support any theory "other than that Corrie was in the bin".

However, there has been criticism from several quarters.

Corrie's brothers, Makeyan and Darroch, with their mother Nicola

Nicola said she was "angry... beyond devastated" at being "misled" by police, saying: "They truly had me believing that he’s in there."

"I can live with Corrie never being found - any parent would just find a way of coping with that - but that’s on the back of knowing that everything has been done to try to find them," she added.

"Why waste £1m searching if you’re not going to finish it?"

Former Met officer Mr Sutton said: "It seems pretty self-evident if you're actually committed to [the search], and you believe you know where he is, then keep looking there.

"We were told that money is not the issue so, if it isn't the issue, then I don't see any good reason for stopping."

Police were arguably facing an uphill battle though. The 120-acre site takes in 96,000 tonnes of waste each year and - in some places - the rubbish is 26ft (8m) deep.

Officers were able to locate the section where waste from Bury St Edmunds would have been deposited, but even this took months to search.

The five-month delay between Corrie's disappearance and the start of the search would also have hindered their efforts.

Forensic pathologist Dr Stuart Hamilton said if Corrie's body had been crushed in the lorry, it would have decomposed at a faster rate.

It would also have made it difficult to carry out tests if his remains were found.

"A lot of information will have been lost, and there would be a greater potential for contamination," he said.

"Even if a fresh body [was in the landfill], there’s so much DNA going on [in the waste], the potential for contamination is huge."

A scrap of clothing, a shoelace, a mobile phone cover, could all have answered the questions they were asking.

But there was nothing.

Suffolk Police have said no new rubbish will be disposed of in the area where they have been searching until a review of the investigation has been carried out.

Corrie's father Martin and stepmother Trisha

Corrie's father said he welcomed this.

"From the leads and the facts the police have, he must be in the landfill," he said.

"If it does come back that Corrie’s in the landfill, I fully expect them to search there again.

"That’s my son in there."

April Oliver gave birth to a healthy baby girl in June. She named her Ellie-Louise.

During the later stages of her pregnancy she had posted a photo of herself alongside an emotional statement on her Facebook account.

She was holding a pair of baby boots, similar in style to the ones Corrie was wearing on the night he went missing.

"Your daddy would be proud of you my little one and would love you as much as I do," she wrote.

"Corrie will be a part of both of us forever and no-one can take that away."

They had been in a relationship for five months when he went missing.

April with her baby daughter, Nicola's mother Pat Spencer and Nicola

When the personal trainer announced her pregnancy, she described her boyfriend as "just the sweetest and most outgoing person I've ever known".

Thanks to the high profile campaign to find him, his daughter will at least have some sense of who he was.

A couple of months after Corrie went missing, Nicola posted a video of him sitting in the back garden singing "I Want to be Popular" from the musical Wicked.

"That just sums that boy up completely," she said.

She has pledged never to give up trying to find out what happened to her son, saying she owed it to the members of the public who had supported her.

In August, she also said her granddaughter gave her a strength she never realised she had.

Writing on Facebook, next to a photograph of Ellie-Louise, she said: "Some days are difficult.

"Trying to find something positive in each day always helps. I am sharing a photo with each of you on this page, it was taken this morning while we were all sitting in the Suffolk sunshine.

"This is the hand of one of my sons being held by the daughter of his brother.

"This photo, to me, is simply beautiful. It gives me a strength I never realised I have.

"There are still so many unanswered questions about what has happened to Corrie, but I do feel confident that all these will be investigated and answered.

"So many of you keep asking questions we are also still asking, I just wanted to let you all know my determination to find Corrie is as strong as ever."