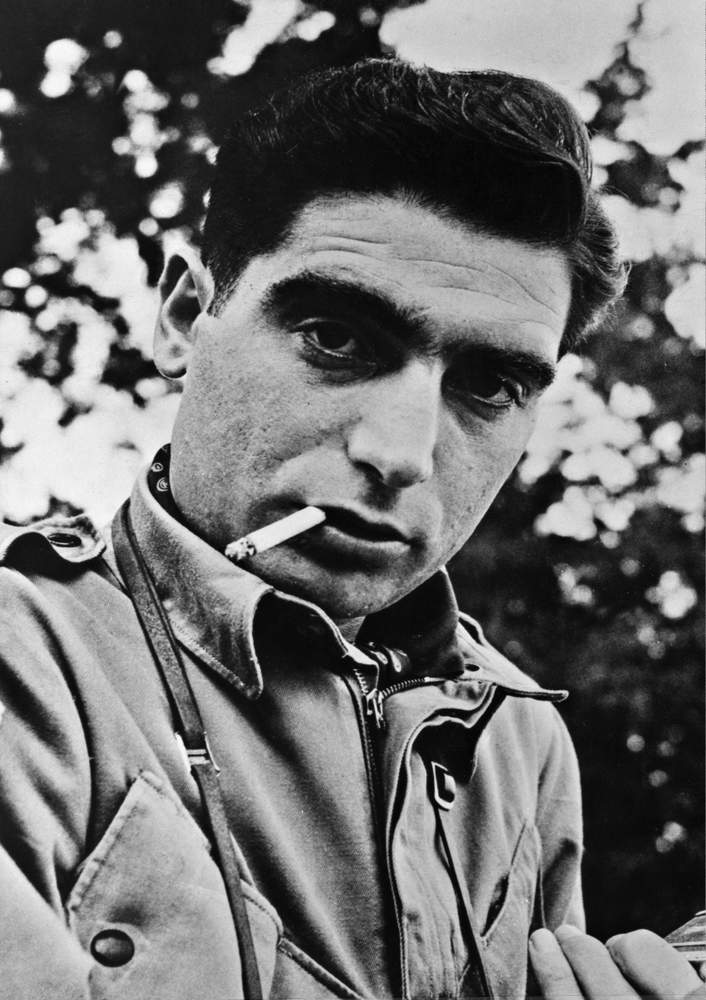

The Swapper is a story about the internationally-acclaimed British documentary photographer David Hurn; it is a story of a dyslexic, Welsh schoolboy written off as being "a bit thick" and an extraordinary "succession of bizarre coincidences" which would propel him into the ranks of photography's elite.

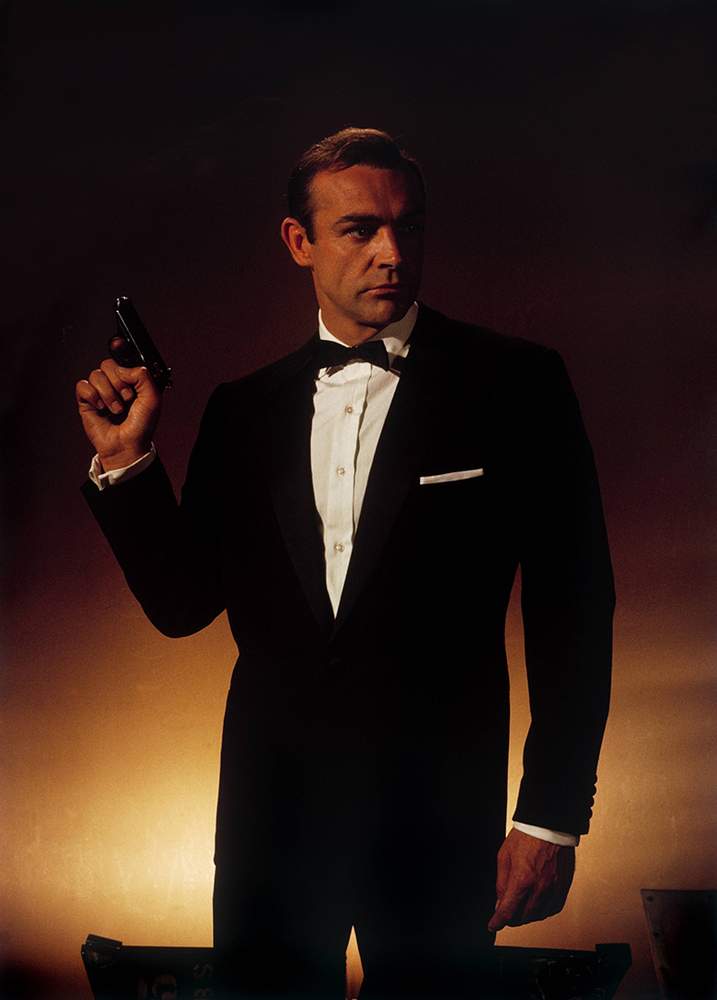

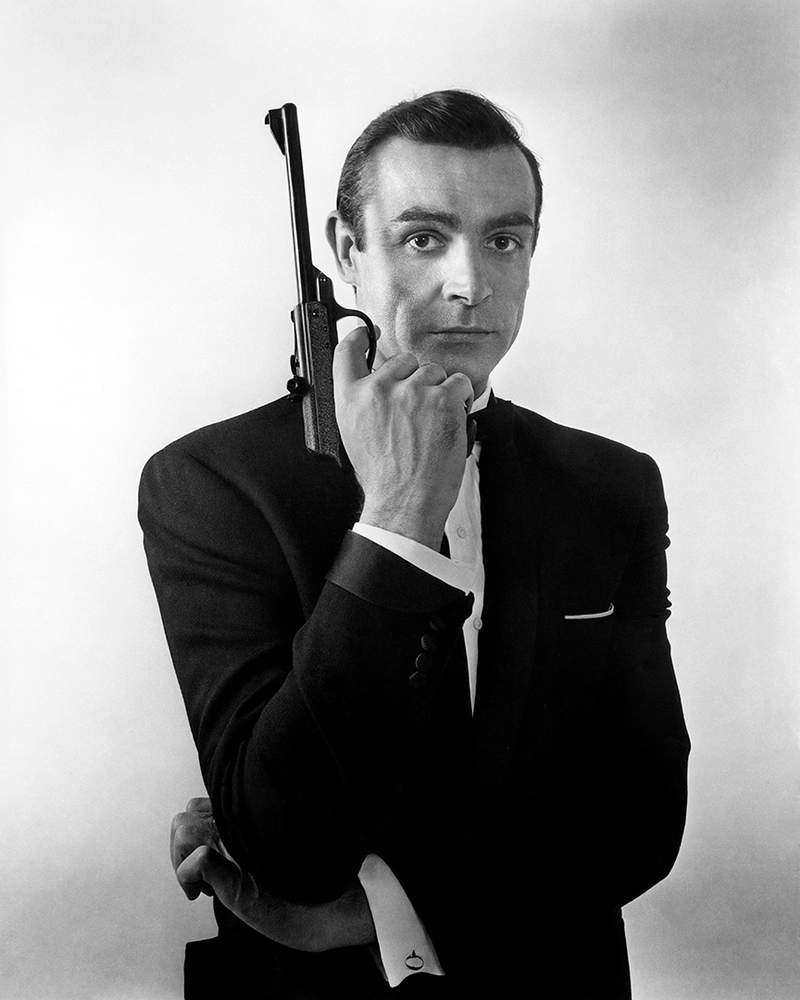

A fixture of Sixties London and the Hollywood inner sanctum, his images of Jane Fonda as Barbarella, Sean Connery as James Bond, and the Beatles on the set of A Hard Day's Night, became icons of the 20th Century.

But they are mere window dressing on a body of work so influential that recognition by him is now regarded as something of an anointing of careers.

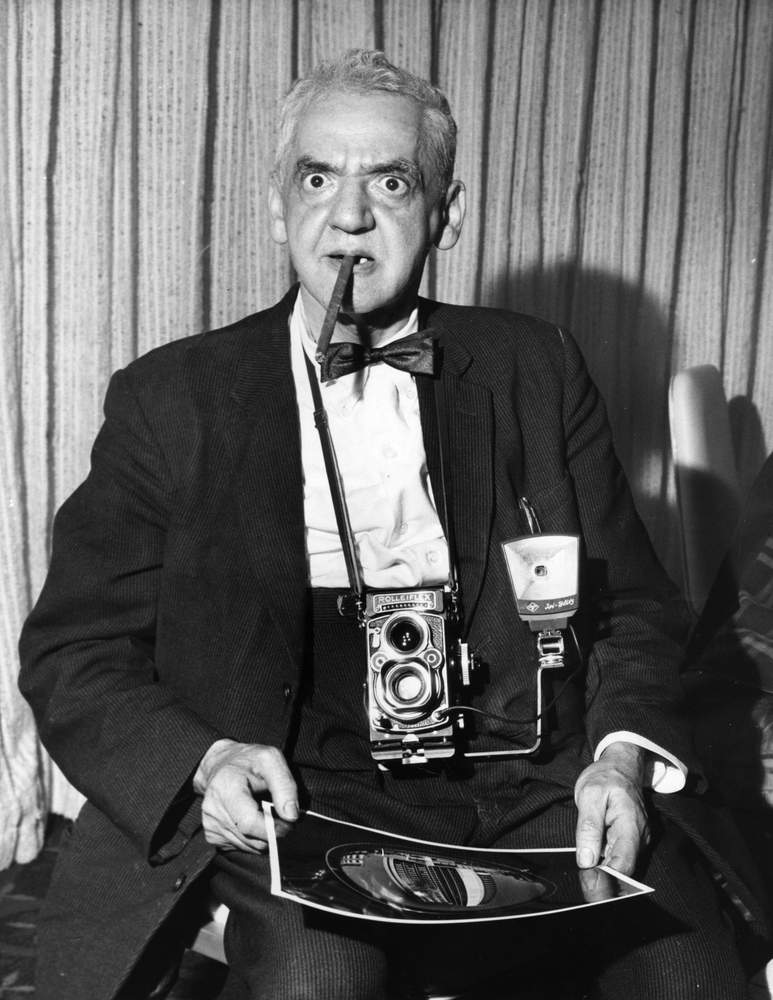

David Hurn is a luminary of Magnum Photos.

Magnum is the stuff of legends. Being invited to join its hallowed ranks - there are only 62 working members in the world - is notoriously difficult; think of it as a kind of SAS, Harvard, an Olympics gold medal of photography.

It is one of the most revered and exclusive organisations in the world which has documented life on virtually every corner of the planet over the past 70 years. That one famous photograph that sticks in your mind? Chances are it is a Magnum shot.

Its photographers have informed generations with some of the most indelible, mind-blowing, thought-provoking, disturbing, entertaining and curious images of our time.

Once nominated by existing members, you run a rigorous four year, three-stage gauntlet of continually proving your worth. Only the chosen few survive to be voted in as fully-fledged members.

"One of the first emails any new nominee will receive, on being accepted by Magnum, is from Hurn, inviting them to exchange," says Martin Parr, out-going president of Magnum Photos.

"Everyone always willingly agrees; they select their favourite Hurn image and vice versa."

To swap with David Hurn is a flattering entrée into the big time for photographers both inside and outside Magnum, young, old, established and lesser-known.

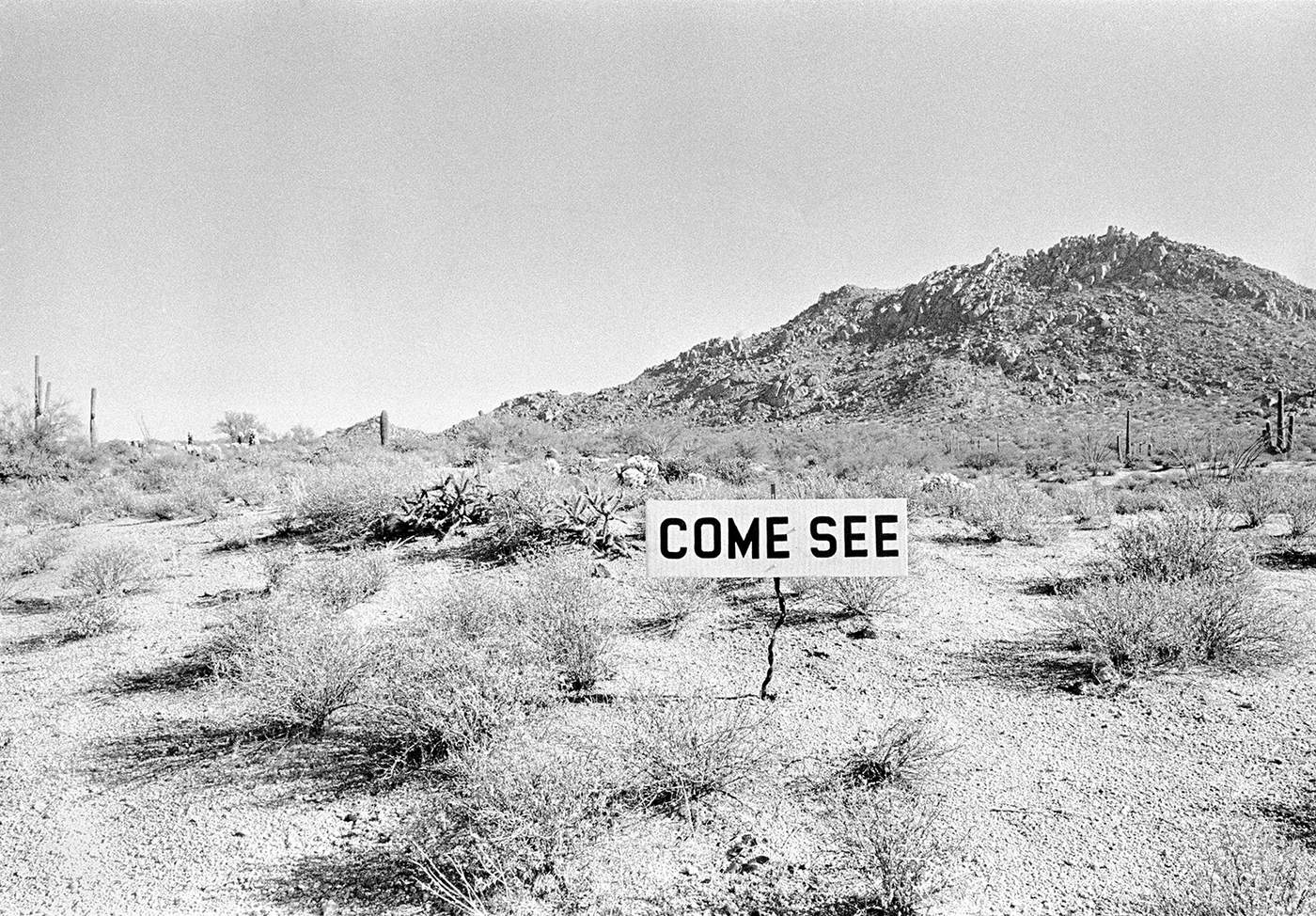

It is continuing a tradition started by Hurn in the late 1950s. Just as then, whenever a photographer's talent catches his eye today, he approaches them to swap a print.

His collection - now a 700-strong who's who of photography - is the subject of a major exhibition entitled 'Swaps, Photographs from the David Hurn Collection' in his native Cardiff.

It heralds the realisation of a long-held dream of Hurn's - the opening of the first permanent gallery dedicated to photography at Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales, where he has recently donated his entire £3.5m archive.

The museum is of deep significance. His mother, perhaps recognising something in her dyslexic son whom teachers had written off, would take him there on weekly visits. The marble-floored halls of Rodin statues and Brangwyn paintings ignited an insatiable curiosity that continues to fuel his work today.

The following sets out a selection of swaps from the exhibition which illustrate influences on his life, a selection of his own work along with the story of the "succession of bizarre coincidences" that shaped his extraordinary career as a self-taught photographer and educator.

And how aged 83, David Hurn has a new quest - to harness the phenomenon of the selfie to inspire photographers of the future.

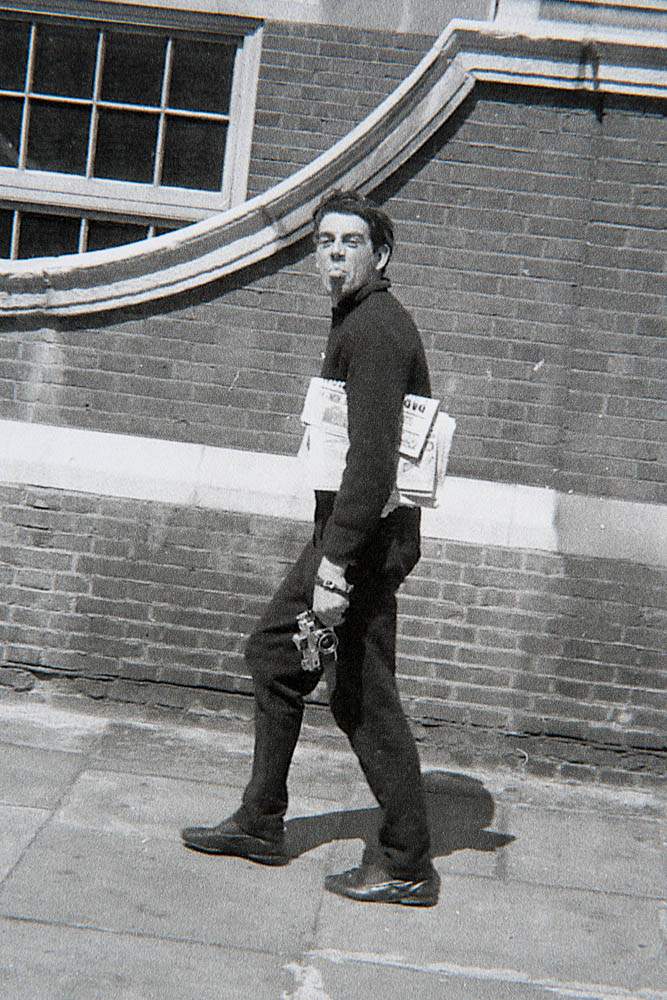

In 1963 Hurn was given the ultimate stamp of cool when a film by Ken Russell about his life work entitled Watch the Birdie was broadcast by the BBC.

It illustrates the versatility and diversity of Hurn's repertoire - a photo-journalist scaling a brick wall to escape a guard dog one minute, a meticulously-lit fashion spread for Harper's Bazaar the next.

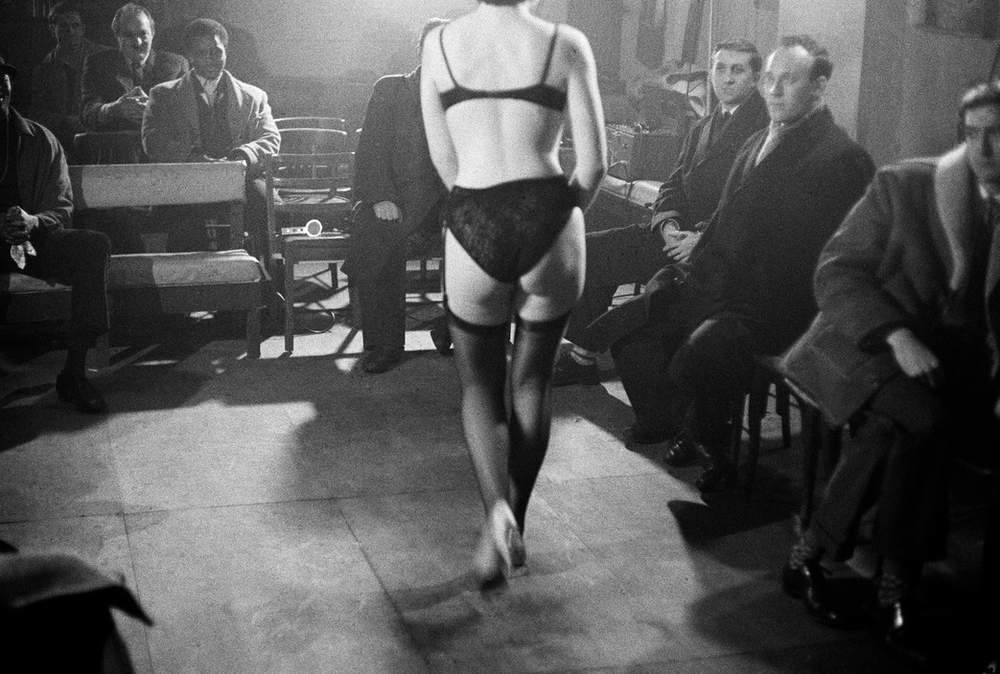

Then it cuts to him dropping in on Little Sisters of the Assumption in Notting Hill Gate to document their work tending to the sick and destitute before roaring off in his custom-built sports car to Joey the Soho stripper who performs 30 times a day, an example of his signature radical and ground-breaking (for the time) black and white photo essays on London's alternative lifestyles or subcultures, drugs, transvestism etc.

Nuns nursing the elderly unable to find hospital beds,Notting Hill,1963

Strip club - thought to be the first of its kind - in Old Compton Street, 1963

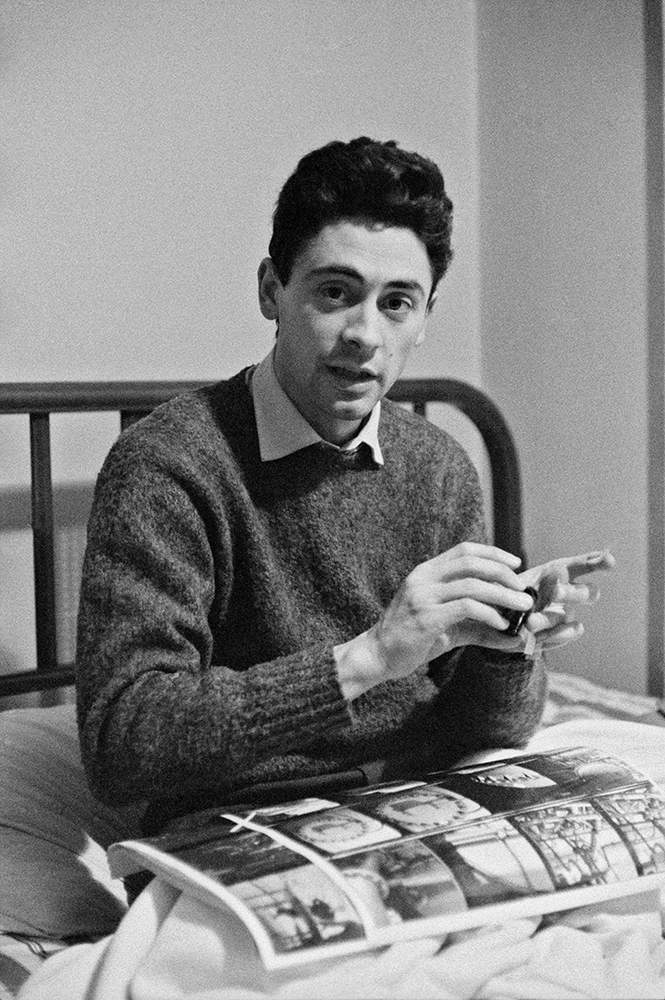

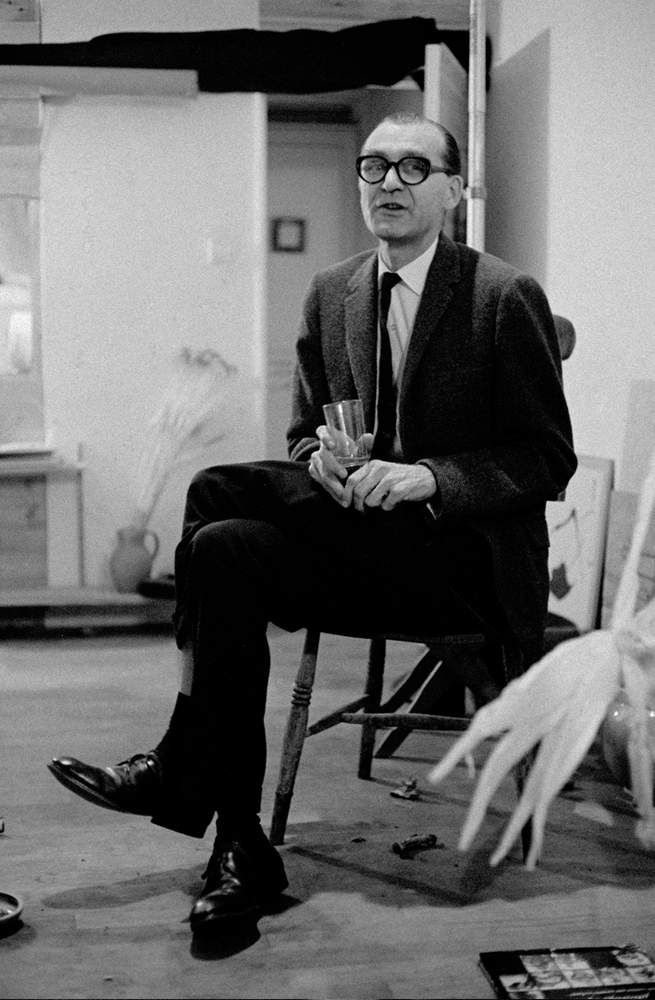

"That was thanks to the example of Elliot Erwitt I'd met a few years before and who was another big influence on my work," Hurn says.

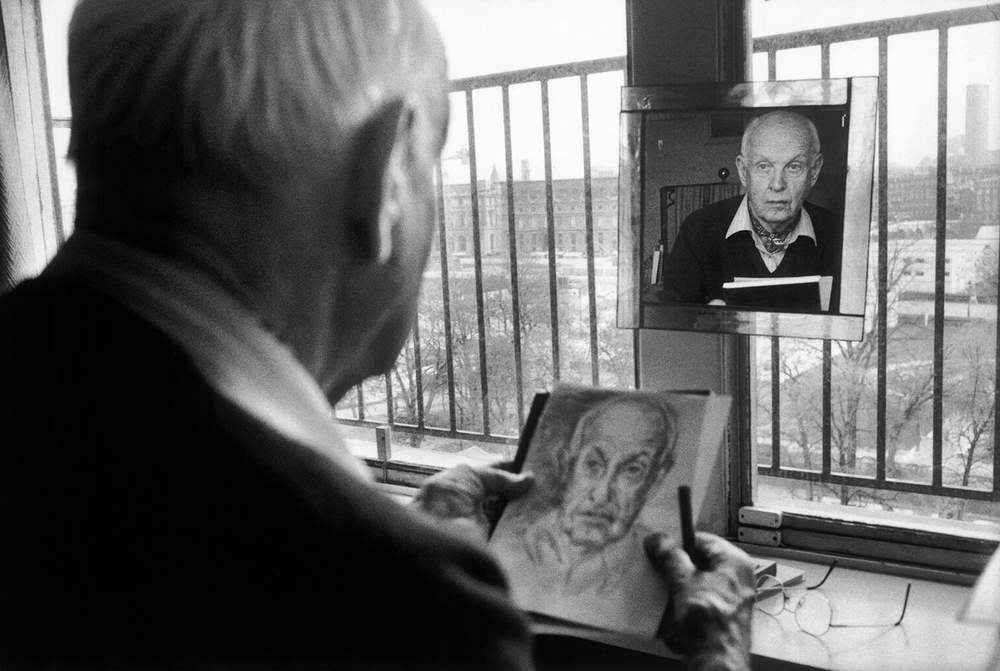

Erwitt, an American advertising and documentary photographer renowned for his quirky and immensely funny take on the absurdity and comedy of everyday life, is described as a master of Cartier-Bresson's so-called 'decisive moment' - that special moment that "transcends the subject and place and can be looked at for years to come" - to the layman it's identifying the exact split second to press the shutter.

"Meeting him was wonderful because he put into my head that you can actually do commercial photography as well as do the work you really want to do," Hurn adds.

"He worked in advertising but he never muddled that up with the fact that he carried a Leica camera with him at all times and shot his own pictures separately to the commercial work he was doing.

Elliott Erwitt

"So thanks to him I never had this hang up about 'selling out' by doing commercial work. It's the practise of doing things to your best ability, regardless of what you're doing."

To supplement his income and free him up to work on his preferred documentary or 'eye witness' photography, Hurn accepted invitations to photograph the film sets of countless films - El Cid, Bond, Alfie - after being introduced to a Hollywood film agent Tom Carlile through his late friend Richard Johnson, the distinguished actor who turned down the role of James Bond.

And on the subject of Bond, Hurn, who worked on the set of the first four 007 movies, shot the iconic film poster for From Russia With Love at his flat in Bayswater's Porchester Court, a creative hub and landmark destination for photographers the world over during the 60s.

An entourage including Hollywood producer Cubby Broccoli, descended along with Sean Connery. But there was one problem.

"The film's publicist came up to me and said 'I don't know what we're going to do. I've forgotten the gun'. To drive back out to the film studios would have taken hours. It happened that I enjoyed target shooting with an air pistol. It was a Walther and had a beautiful box with Walther written on the outside of it. Bond's pistol was a Walther PPK.

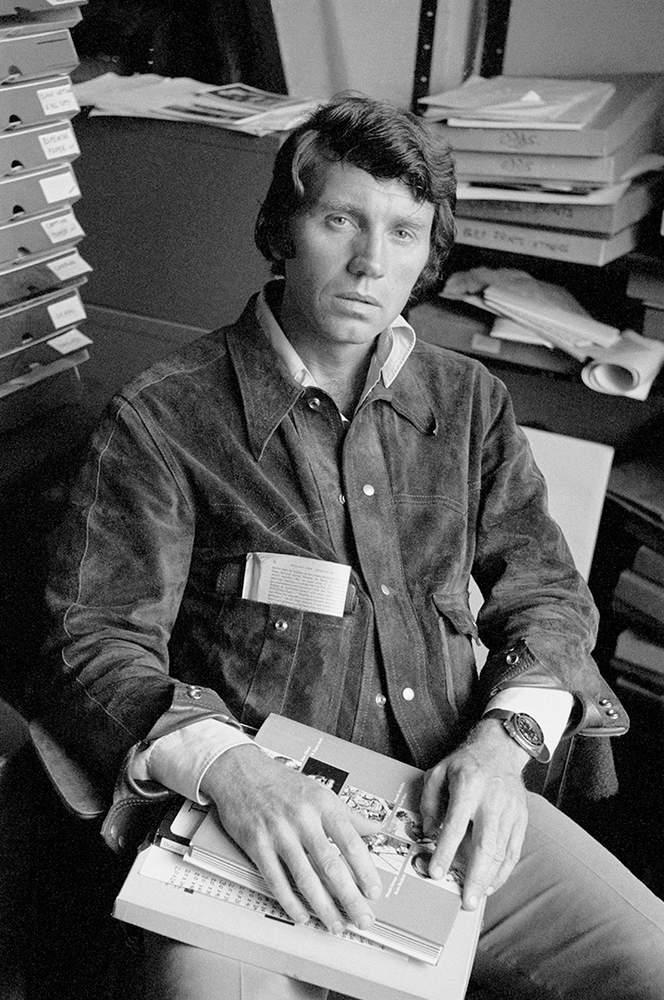

Movie publicist Tom Carlile in Hurn's studio on a Bond shoot. He would later hire Hurn for Barbarella

"I said 'Look, although it's an air pistol and has this great, big long barrel and Bond's has a small barrel, nobody here will know. The mere fact it's got Walther on the box they'll think it's the right one'.

"I said all you've got to do is make sure when they come to do the poster that the long barrel is cut off and it will be ok. But when it came to do the poster art they forgot. So if you look at any of those Bond posters, there's Mr Macho brandishing his air pistol."

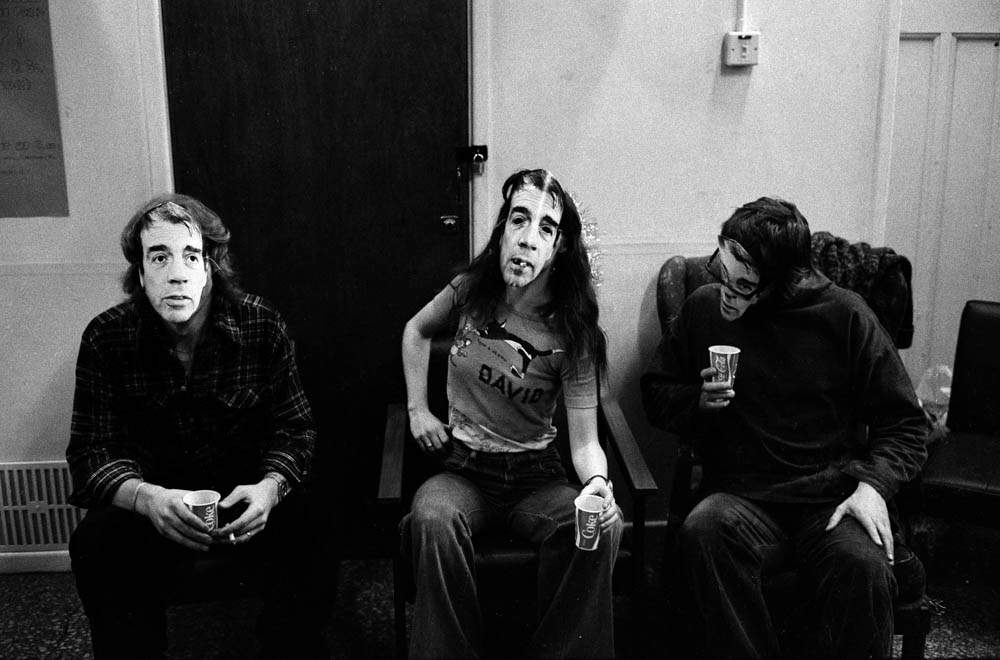

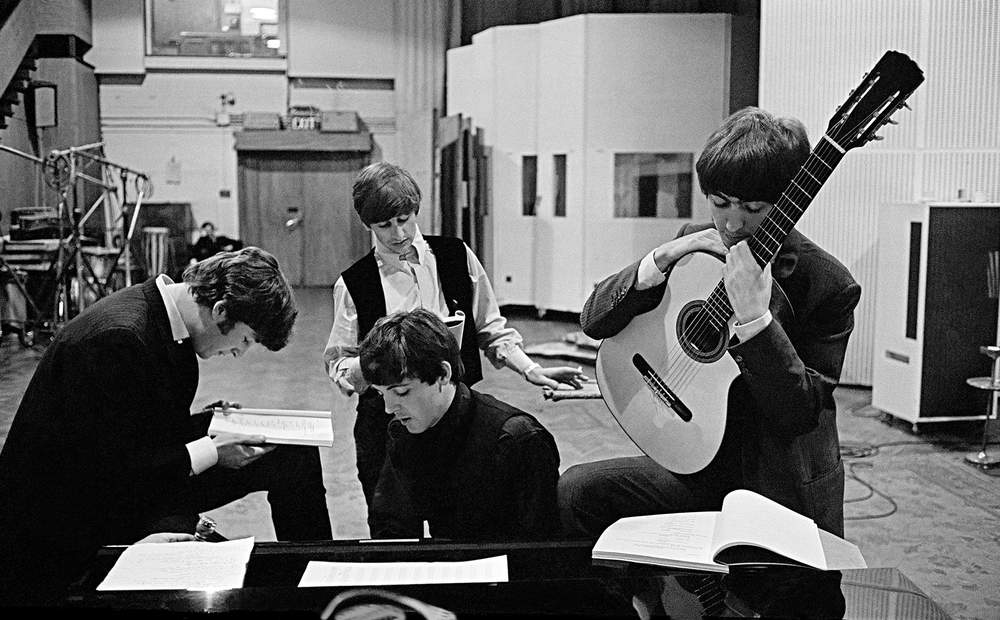

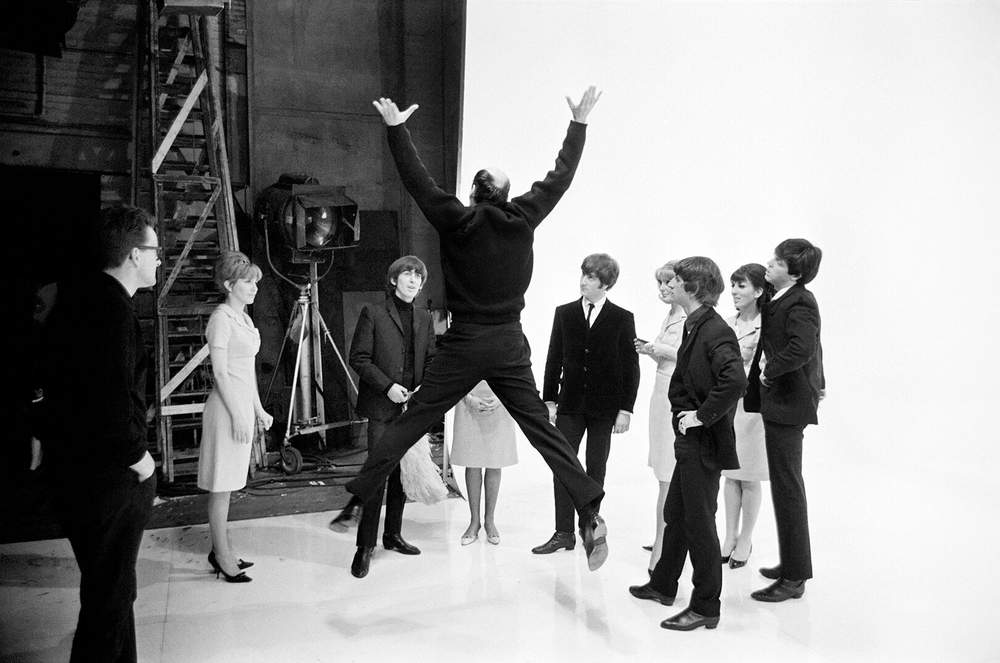

Soon after Hurn was introduced to the Beatles film director Dick Lester who asked him to follow the group around for the six weeks of filming for their first film A Hard Day's Night.

He liked Ringo Starr the best but it was the "exceedingly shy" George Harrison that Hurn would have the biggest impact on by introducing him to his future wife.

One of George Harrison's first encounters with Pattie Boyd

Hurn's friend, fellow photographer Eric Swayne was dating Pattie Boyd at the time.

Swayne was keen to meet the Beatles and Hurn somehow persuaded Dick Lester to allow them onto the set and Pattie became a film extra.

Harrison, who would later write the love song Something about her, was transfixed.

"I introduced her to them all," Hurn says.

"I had no idea that the one had goggled at her more than the others. Of course, I wasn't the greatest friend of dear Eric Swayne from then."

A Hard Day's Night had cemented the Fab Four's place at the forefront of the British Invasion - the storming popularity of British music and culture into the US.

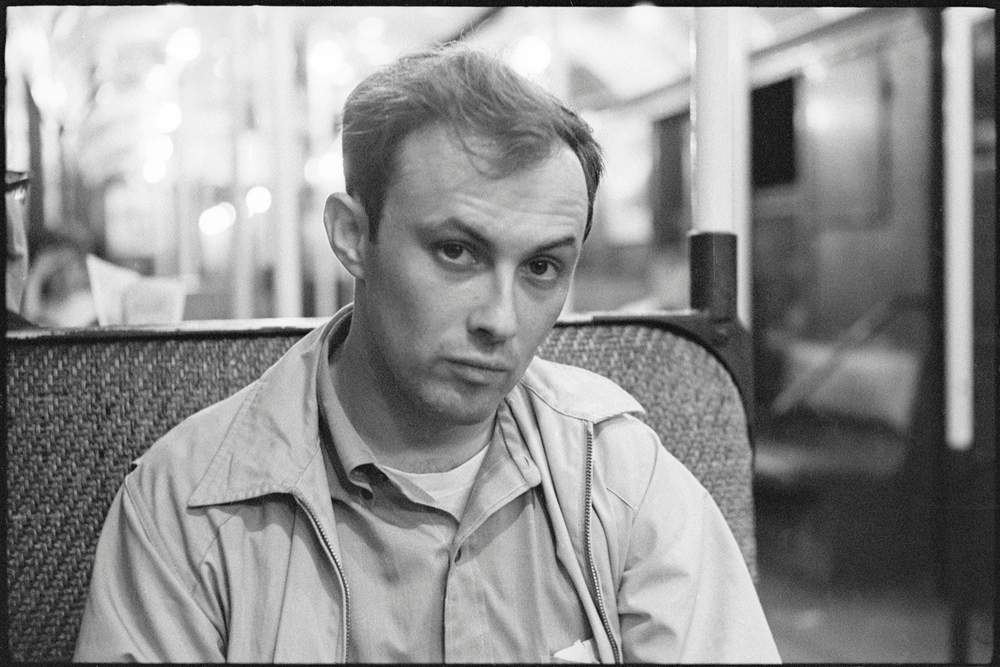

Director Dick Lester giving direction

Hurn, who became an associate member of Magnum a year later in 1965, had played his part in that but it was two years later in 1967 in an altogether more cosmic invasion that he was to become better known.

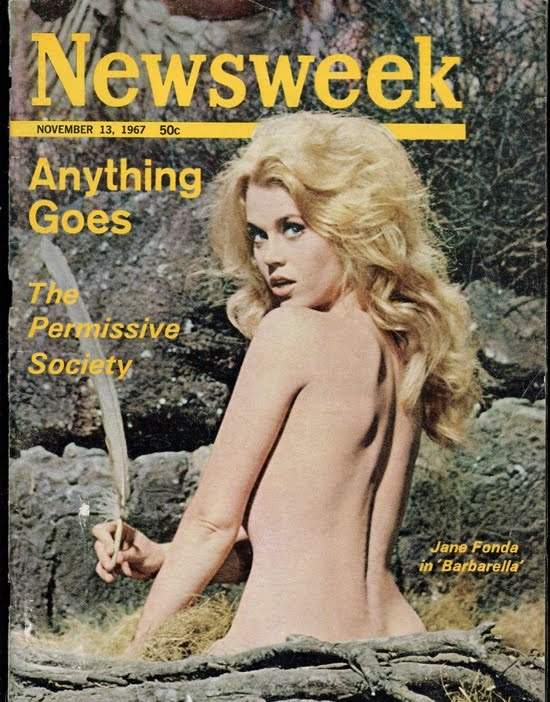

The New York Times described Jane Fonda as the leading lady in the cult sci-fi movie Barbarella as "the most iconic sex goddess of the 60s". But that might never have been the case had it not been for Hurn.

The young Fonda, insecure about her looks and who hated being photographed, was giving film producer Dino de Laurentiis a tough time over the publicity stills and had rejected them out of hand.

"The publicist Tom Carlile phoned me up and explained what was going on," Hurn says. "He said 'Look David, come over to Italy and see if you can sort it out for me and try and calm her down'.

"The moment we met we got on extremely well. She said she felt her face was lop-sided 'like a squirrel with one cheek full of nuts'. I managed to make her laugh and somehow won her confidence.

"We became very good friends and I ended up spending nine months with her and her then husband Roger Vadim on the set and at their home. She's still a friend. We met up in LA a few months ago."

The Barbarella images graced the covers of 126 magazines around the world.

Newsweek reportedly achieved both its greatest news-stand sales and its highest number of subscriber cancellations when it published pictures of a naked Fonda on its cover under the headlines Anything Goes, The Permissive Society.

By this stage Hurn's hero and inspiration Henri Cartier-Bresson had actually visited his famous flat to personally examine his contact sheets shortly before he was voted in as a full member of Magnum in 1968. "It was like seeing God," he says.

Hurn's then wife, model and actress Alita Naughton with their daughter Sian

Hurn led a rarefied life; an internationally-successful career, a beautiful wife, accomplished and celebrated friends, and an Aston Martin parked outside the front door.

The dyslexic schoolboy from Cardiff had done pretty well for himself.

But just over a year after Barbarella hit the screens, Hurn had left London, his marriage had broken down and he was living in a VW camper van on the banks of the river Severn near Newport, south Wales.

Credits

Author

Ceri Jackson

Web production

Philip John, Sophie Mutton, Ceri Jackson, Gwyndaf Hughes

Video production

Philip John

Cover photo

Brian Carroll, Ffoton

Photo credits

Magnum Photos, Getty Images, International Center of Photography, Oakland Museum of California, Ella Murtha,

Eva von Oelreich

Built with

Shorthand

Date 29 September 2017

All images subject to copyright