Warning: This article contains details that some people will find very distressing.

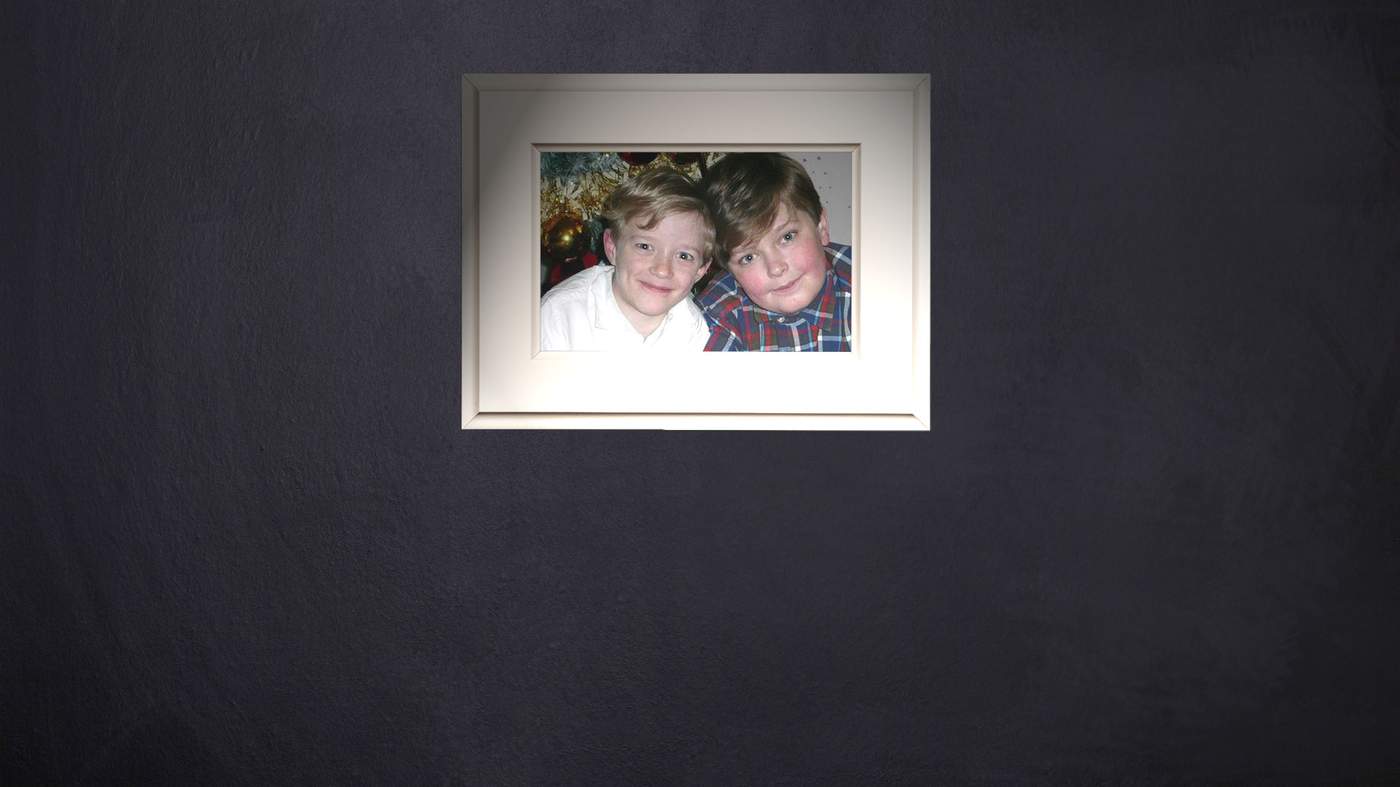

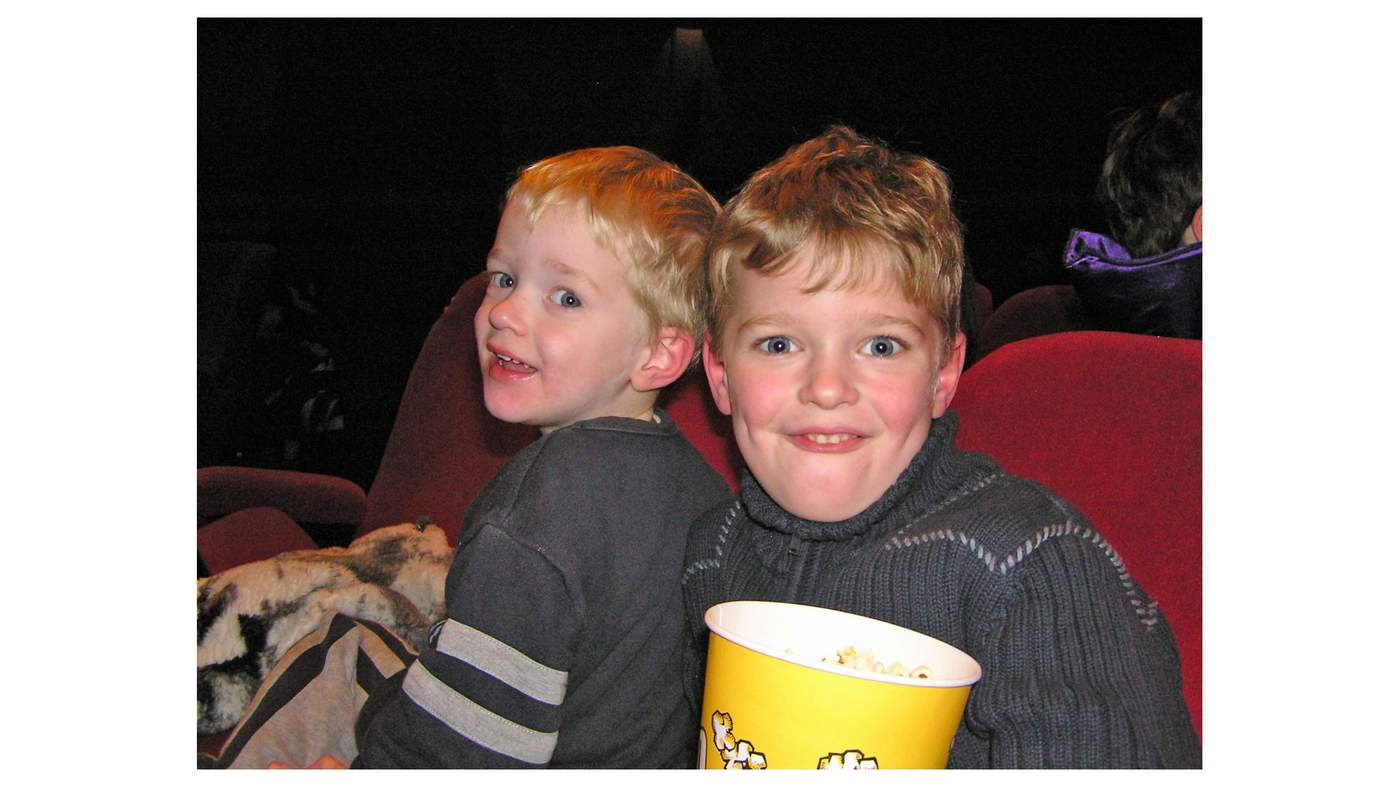

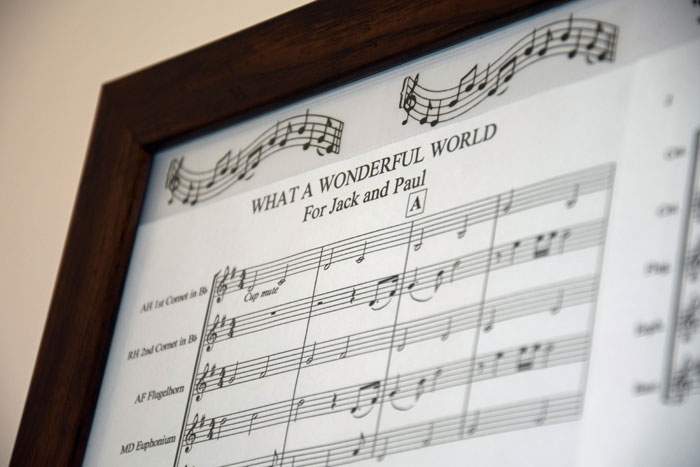

Jack was the older of the two. He was 12 and he was a musician.

“Music ran through his veins like water runs down a stream.”

He was a talented trumpet player. His music teachers thought he might go all the way. He dreamed of studying music at university. A lovely, quiet, gentle boy.

Paul was cheeky and full of confidence. A good sportsman - a runner, a sprinter.

“I think he ran before he could walk.”

Jack was. Paul was. Both are now dead.

On Wednesday 22 October 2014 the boys were murdered by their father.

Claire Throssell’s flat is full of photos and other reminders of her two sons.

She will never forget the last time she saw them.

Since then she has been fighting. Both to remember them but also to try to prevent a tragedy like this happening again.

Claire had lived all of her life in a small market town in South Yorkshire. She met her husband Darren at a work function one evening and the relationship moved quickly.

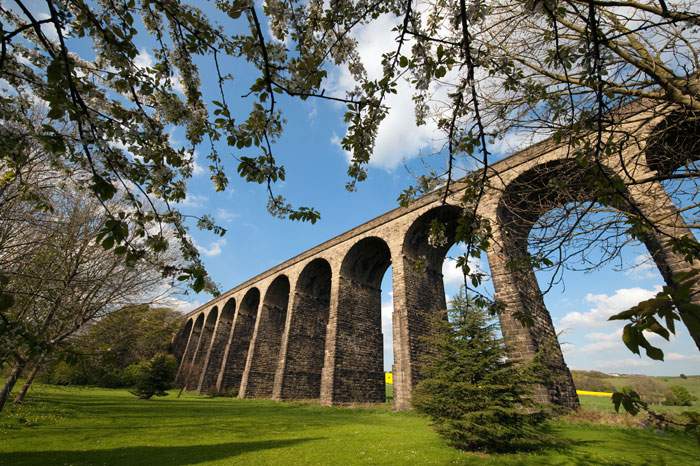

His attentive behaviour seemed to be just part of the intensity of a young relationship. There were regular flowers and phone calls. They married and children followed. The family were living in a house by a viaduct, a river and a park.

But Claire began to realise something was wrong. Her husband was too “caring”. He was too interested in what she was up to. His behaviour was too intense. There started to be something slightly sinister in his character.

Claire now knows this was coercive and controlling behaviour. It’s against the law in England and Wales, and Scotland moved to legislate this year. A law has been drafted in Northern Ireland but is yet to go through.

Professionals are trained to look out for manipulative and controlling actions. It’s when a person, typically a partner, repeatedly behaves in a way which makes someone feel dependent, isolated or scared.

Claire’s husband completely controlled her life. Repeated phone calls while she was at the supermarket, insults about how she looked, calling her stupid, distancing her from her friends and family, controlling the finances.

“It had got to a point where I couldn't even look in the mirror and recognise the person that was looking back at me. My self-confidence had gone.”

The boys were becoming more and more cautious around their father. He imposed heavy discipline. With Paul, the younger, his father became bullying over his food - he was made to eat things he didn’t want to. One time he was forced into a chair to eat.

The boys regularly saw their father insulting and shouting at their mother.

“Jack in particular would say, 'Stop threatening my mum'.”

It was April 2014 and after many years of this difficult life, Claire decided she was leaving for good.

“The whole process was made even harder by the fact that he was very controlling and aggressive, and things deteriorated very quickly between us.”

Her husband stayed in the marital home, while Claire and the boys moved into her mother’s house. Initially Claire and her husband agreed on shared custody, but her husband’s controlling and aggressive behaviour was escalating. He had a track record, having once been cautioned for assaulting a neighbour.

The police were aware that there could be trouble. They put a high priority tag on Claire’s phone and her mother’s address - in the event of an emergency call, they would send an immediate response car.

But Claire worried every time her boys went to see their father.

In June, Paul became very upset at school. He told his teachers that his dad had hurt him in the past - dragging him along by the throat.

This was the final straw. Claire applied for an emergency residency order to stop the shared custody of the boys. As well as Paul’s complaint, Claire’s submission included two remarks her husband had made to her - that “he had nothing to live for and intended to commit suicide” and that “he can understand fathers killing their children”.

A court hearing concluded with an interim arrangement for much more limited access to the boys for Claire’s husband. Although he had agreed to this, along with Claire, this angered him further.

Things really got out of control, because he'd lost control.”

He took Claire’s belongings from the family home and threw them into the front garden of her mother’s house.

Abusive texts and messages followed in a torrent. After he threatened to kill himself, Claire called the police.

Even then he was trying to control Claire. He told the police that he would only talk to them if she came to the house as well.

Claire always had a feeling that her estranged husband was capable of hurting the boys. She still questions whether she could have done more to prevent the contact visits they had with their father.

“Things really got out of control, because he'd lost control.”

The boys were allowed to see their father for five hours each week on Sunday afternoons and Wednesday after school, from August 2014. This was unsupervised.

But Claire knew the boys didn’t want to spend any time with their father.

By the middle of October 2014, the divorce had come through.

Cafcass - the Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service - was involved. Claire had warned the service that her estranged husband was often volatile and aggressive, especially when he was told things he didn’t want to hear.

There had already been two hearings. The final one was set for 17 November 2014.

A “Section 7” was requested. This report was to include the wishes and feelings of Jack and Paul so the judge could help make the decision about the boys’ contact with their father. It was expected to be ready two weeks before the November hearing.

That hearing never happened.

The morning of Wednesday 22 October 2014 started off the same as any other morning. Claire went to drop Jack off at his grammar school. She said “I love you”, as she always did.

He called back, as he always did, with Buzz Lightyear’s line from Toy Story, “To infinity and beyond”.

Jack always looked back once. But Claire remembers on that morning he turned and looked back a second time before walking into school.

Claire dropped Paul off at his school. He had the exact same ritual as his brother. When she said “I love you”, he said, “To infinity and beyond”.

She went to work.

The boys were due to see their father after school. He had put a train track in the attic in the old family home. He had texted that morning saying he had two new trains for them, and all he needed was two drivers.

Just before 5pm, Claire says she got a call from an officer at Cafcass. The officer later said the call was routine, but Claire gives a slightly different account of it.

The boy’s father had come into Cafcass on Monday that week, two days before, and it hadn’t gone well.

The Cafcass officer wanted to know - Claire recalls - if the visit between the boys and their father was going ahead. Claire said they were already there. The Cafcass officer suggested Claire keep an eye on them when they returned from the visit.

It took 15 minutes for my life to end... and my existence to begin”

When she got home from work, Claire felt deeply uneasy.

There was a knock at the door. Claire’s mother said it would be the boys, back early.

But the boys would never have knocked. They used to rush straight in.

Claire found a policeman at the front door. “There's been an incident at the house.”

She said: “He's done it hasn't he? He's done something to them.”

The officer wouldn’t say more but the look on his face was enough.

“I knew, I knew.

“It took 15 minutes for my life to end... and my existence to begin”

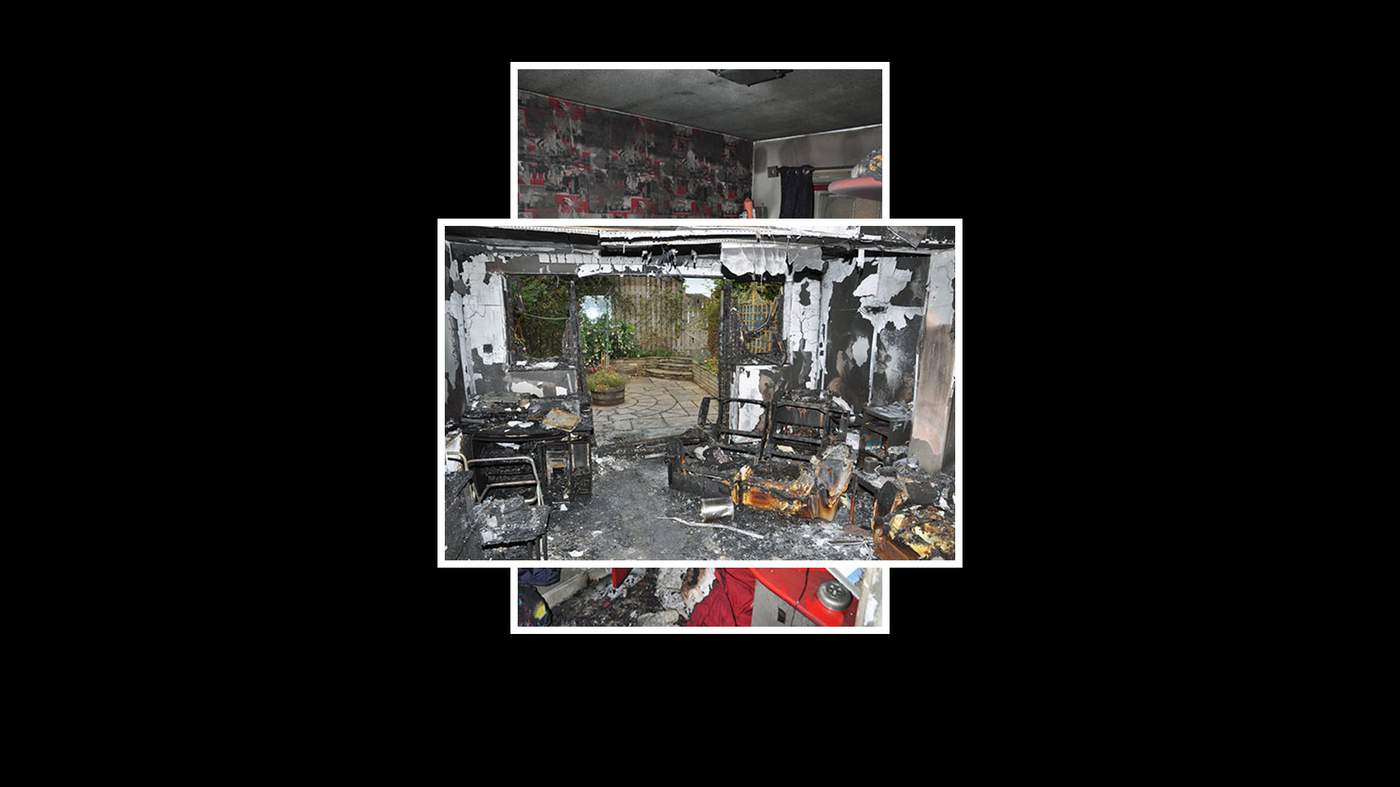

Jack and Paul had gone up into the attic to play with their new trains. Their father had blocked the front and back doors before setting fires all around the home.

He joined them up in the loft, closing the hatch and trapping them.

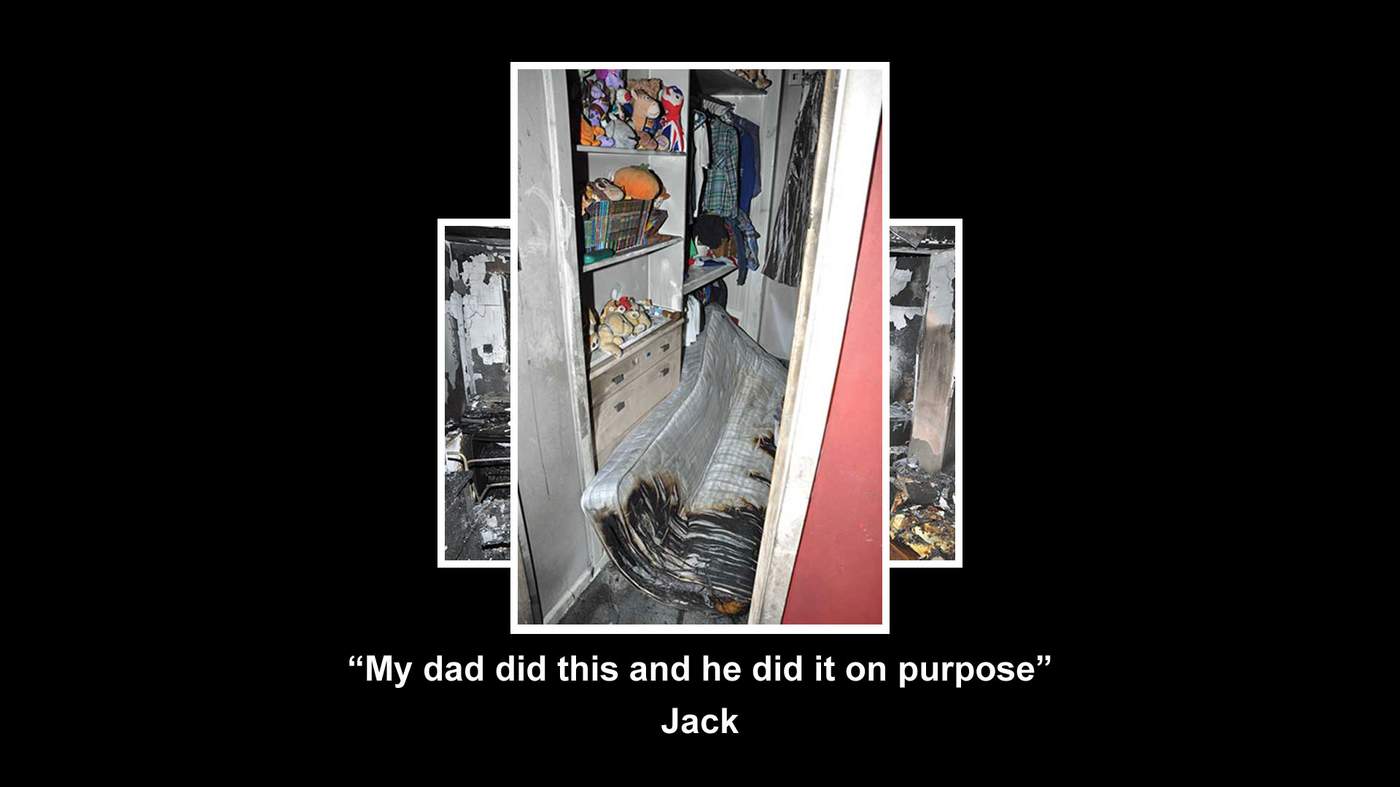

The first firefighter found Jack on the landing and picked him up. But he was already badly burned. He had tried to escape and get help for his brother.

Despite his condition, he went on to reveal what had happened. “My dad did this and he did it on purpose.”

He and his brother were rushed to Sheffield Children’s Hospital - Jack had 56% burns and Paul was unconscious.

Their father was taken to another hospital in the city, where he died.

A police car sped Claire to the hospital to see her children.

“I went into a room and the consultant was drenched in sweat.

“There was Paul and they were doing CPR on him. I knew pretty much that there was no hope.”

The doctor stopped the CPR and Claire held Paul in her arms. “My tears were in his hair. And his hair was damp. His eyes closed and it was just as if nothing... was looking back.

“I promised him that no other parent would have to do what I did... and hold a child in their arms whilst they died, knowing it's at the hands of somebody who should love and protect them.”

Jack was transferred to the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital for specialist burns treatment. Claire stayed by his bedside for the next five days. She finally said goodbye on 27 October.

That was the day that Jack had been due to give his views about his father for the Section 7 report. He never got the chance to be heard.

Only a very small proportion of abusive spouses go on to commit murder.

Each time though, questions are asked as to whether the authorities could have done more.

There are serious case reviews.

Claire feels that Cafcass let down her children. Claire learned from the police that the boys’ father had blocked the family liaison officer in her office on Monday 20 October - two days before the fire.

Claire says that if only she’d been told promptly about that, she would never have allowed her sons to see their father later in the same week.

Cafcass does acknowledge the meeting had to be stopped but doesn’t believe there was any indication that the boys' father might cause immediate harm to them.

“Cafcass accepted the findings of the coroner and the serious case review, who agreed that the children died due to unlawful killing and that no public authority could have predicted or prevented the tragedy,” a spokesman says.

“However, we do regret that some aspects of our work with Ms Throssell’s family did not meet the high standards we set for our staff.”

Cafcass says it has now improved the way it assesses risk. “We continuously develop our practice and this year launched a Domestic Abuse Practice Pathway, which provides our staff with a clear, robust framework to assess cases involving domestic abuse.”

The serious case review into Jack and Paul’s deaths at the hands of their father said: “The vast majority of estranged fathers would not consider such actions and... there is no known way of identifying those who will do so.”

But while it is only a small minority who murder, there is a great deal of other harm that is done.

Could more be done to put the interests of the children at the heart of how we deal with abusive relationships?

Claire now spends her time campaigning and working with the charity Women’s Aid to highlight the effects that domestic violence and coercive behaviour have on children.

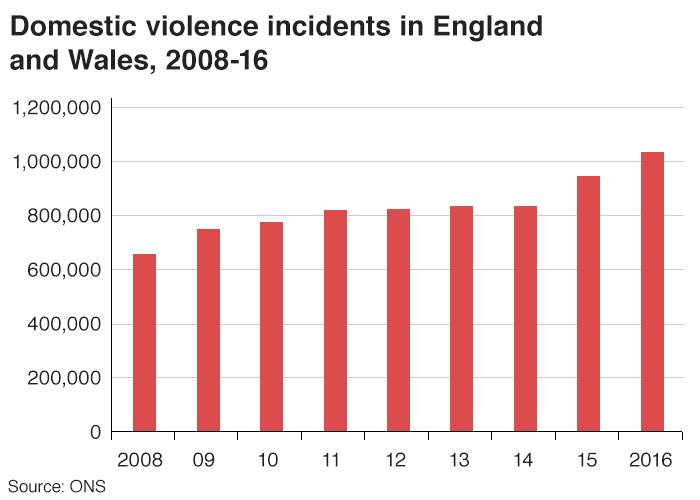

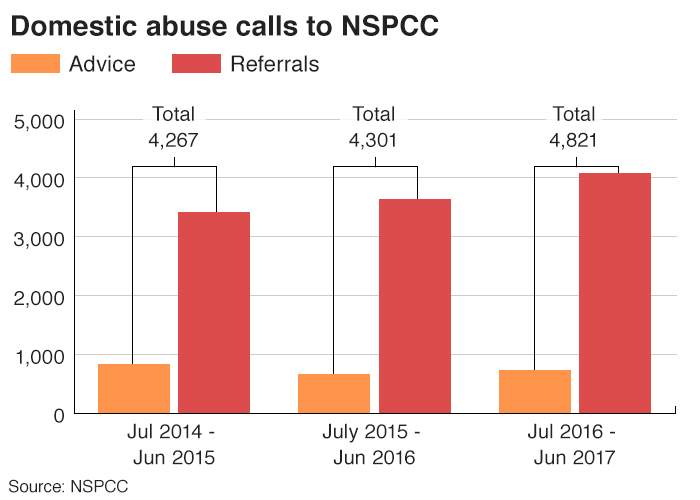

The charity points to statistics that are sobering.

Women’s Aid want the authorities to understand domestic abuse and coercive and controlling behaviour. The group says that a joined-up response, early intervention and support are essential.

Claire says that when children witness domestic abuse, it ends up “going into their whole being”.

Jane (not her real name) knows exactly what Claire is talking about. Jane has taken her children and left her controlling and physically abusive partner.

She put up with nearly five years of terror. She knew this would affect the rest of her children’s lives. One night she fled with them in a taxi.

Jane had been trapped in a life of control.

The curtains had to remain shut, family days out didn’t exist. She was told what to wear, she was told who to speak to, and she was made to lie to social workers. She was not allowed to show affection to her children. Jane was left on her own, to care for her children as well as those from his extended family, while regularly being insulted.

“Yeah I've had black eyes. Like he never outright punched me in the eye. But I've had elbows and knees… or my head would be bashed off something or stuff might be thrown at me. All of this happened while the kids were there.”

As Jane recounts the desperate times, tears pour down her face.

“You'd be in the middle of having this fight and you'd be looking at your kids, and you could just see the fear. You can't get out of the situation. I hated the fact that they were so confused by it.”

Life was never normal. If the children ever expressed interest in a game or an activity, they were always made to feel it was wrong. They were never allowed to make a mistake.

Jane’s case isn’t rare.

Dame Vera Baird QC, Police and Crime Commissioner for the Northumbria police force area, has long campaigned about domestic abuse. She has been introducing changes. Northumbria Police was the first to carry out force-wide training on how to spot coercive and controlling behaviour.

Now Dame Vera wants to focus on the court system and give more protection and understanding to victims. She believes there is a problem when access arrangements are being made for families where domestic abuse is prevalent.

“The perpetrator can pursue them right or wrong through the family court and actually use that court really to carry out abuse and continue the abuse.”

The Ministry of Justice has accepted the law must change. “We will legislate to give family courts the power to stop abusers from cross-examining their victims in family proceedings,” a spokesman says. “And we are investing more than £1bn to modernise our courts system, to make it more sensitive and accessible to victims and witnesses.”

Of course, there are those who think it's easy to go too far in criticising the family court system, and who point out their duty to try to make sure children have their parents in their lives.

“Obviously there are tragic cases that have been dealt with by the Family Court and one death is too many,” says Chris Fairhurst, a family law specialist at Slater and Gordon, “but if you look at the private law cases alone that Cafcass is dealing with, it is in excess of 40,000 a year and generally the balance appears right, although there's always room for improvement.

“The beauty of our family law system is that it is largely discretionary and flexible, treating people as human beings, taking account of their faults. By all means you should have guidance on these types of issues, but once you start tying the hands of judges too much, you can enter dangerous territory.”

It’s the effect on the children that still haunts Jane. One of the boys has become very quiet and withdrawn while another struggles to control his anger.

With the help of family and a local charity, Jane is rebuilding her life in a different part of the country. The children are settled in school, and she has a light, airy, clean, welcoming house for them all to come home to. Jane is now getting ready for Christmas. She is determined to make special memories for the rest of their childhood.

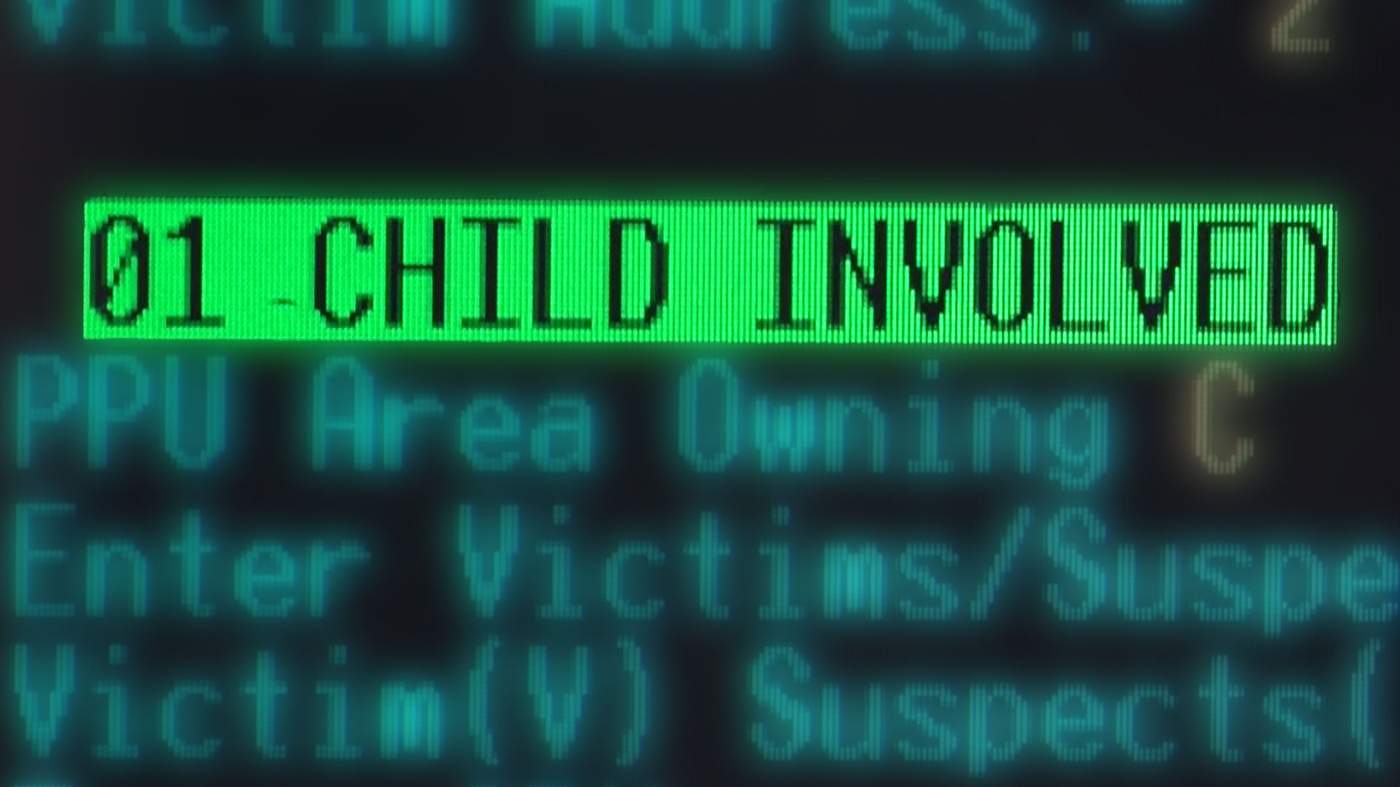

In Northumbria Police’s control room, domestic abuse calls are prioritised.

“It’s come in as a domestic, with reports of someone having been stabbed with a screwdriver.”

“Has she got any children at the address do you know?”

For any ongoing domestic violence call, a response car goes with blue lights and sirens. The caller is kept on the line.

Mark has just had a caller hang up. “I rang it back and spoke to the caller. She said that her ex-partner had threatened to beat her and her 12-year-old child up.”

He assures her someone is on the way immediately.

The following week, PC Jason Parkin and PC Michael Paul are on a late shift in Sunderland the night we join them.

A member of the public has rung in, after seeing a woman being treated violently in the street:

“There’s a male who’s got tight hold of a female’s arm and has hit her on the back, she was quite distressed and shouted ‘get off me’.”

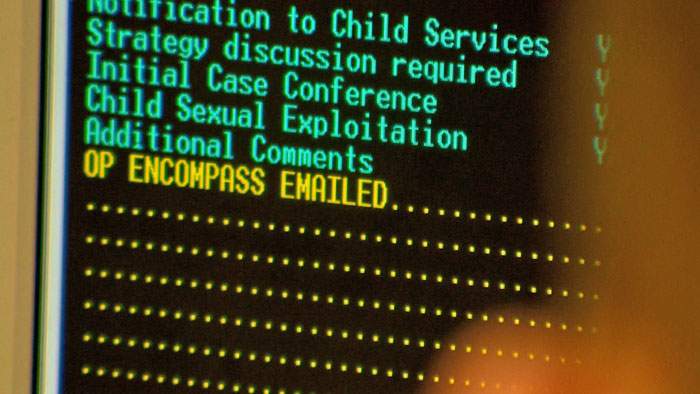

The team switch on their blue lights and they’re off. If children are involved in a domestic violence call, it is flagged on the police computer system.

Every morning a special team at Northumbria Police HQ scans a log of calls, ready to pass information on to schools. Steve Dixon, leader of the Protecting Vulnerable People team, recounts a typical case.

“Mam has been assaulted by dad, a child has been present during this incident. The child is 11 years old. Mam has been taken to hospital and dad has been arrested at the scene by police.”

When that 11-year old comes into school, there will be someone to greet them who will understand what’s happened to them.

It’s all down to Operation Encompass.

It began in a Devon primary school when head teacher Elisabeth Carney-Haworth noticed a dramatic behavioural change in one of the children.

‘’We didn’t know why. The child couldn’t tell us. We spoke to the child’s mother and she couldn’t tell us either. ‘’

The little boy had been exposed to domestic violence at home. But it took months for Elisabeth to find that out. She was furious that she had not been told earlier, so that the school could have acted faster to help.

Operation Encompass's website

She knows how devastating domestic abuse can be to children. “MRI scans show that the bits of their brains that ‘fire up’ are exactly the same as in soldiers exposed to combat with PTSD.”

When she told her police sergeant husband, David, of her frustration, he agreed that things had to change. Operation Encompass was born with the start of a line of communication between the police and seven schools in Devon.

For each school, the police are in direct contact with a trained “key adult” - usually the head teacher. Whenever a child is caught up in an incident of domestic abuse the school is told immediately.

Elisabeth says: “The first thing we will do is greet that child with a smile. If they’ve not got school uniform on, we can find school uniform. We can check that they’ve had breakfast and that they are all right.

“They need school to be a safe, secure, nurturing environment.”

Now Operation Encompass has been taken up by more than 22 of the 43 police forces in England and Wales. The ambition is to eventually cover the entire UK.

Things are changing. In September, new guidance was published for judges and magistrates in child contact cases where domestic abuse has been alleged.

Sir James Munby, the president of the Family Division of the High Court for England and Wales, made several changes.

Wording now sets out what judges and magistrates are “required” to do rather than what they “should” do in cases where there is domestic abuse.

It's now mandatory for the courts to determine whether children and non-abusive parents will be at risk of harm from a contact order.

The definitions of domestic abuse, coercive control and the harms caused to children have been clarified.

Judges must carefully consider how domestic abuse affects children, and question whether the “presumption of contact” applies.

These all change how the courts and other authorities weigh up risk when it comes to allowing allegedly abusive partners access to their children.

But for campaigners like Claire there is still more that needs to be done.

We met Melissa in the early hours of a Saturday morning. She was sitting in her sparsely furnished flat in the north-east of England. There had been a fire in the stairwell recently and the blackened peeling paint covered the wall. She was curled up on the sofa. She hadn’t eaten all day.

He’s taken everything away from me. I’m in so much pain. It’s ruined my life basically.”

We had arrived with the domestic abuse response car - police officer PC Michael Urwin and Gemma Ridley from Wearside Women in Need, who has years of experience supporting women like Melissa.

PC Michael Urwin and Gemma Ridley

Melissa had been in an abusive relationship for nearly five years. When we spoke to her, the tears came as she thought of the baby taken away by social services. Melissa says she was essentially forced to chose between her abusive partner and her newborn baby.

“He’s taken everything away from me. I’m in so much pain. It’s ruined my life basically.”

The abusive relationship meant that social services couldn’t let Melissa keep her baby son.

“He wasn't bothered. He wanted me more than anything. He controlled us really badly.”

Melissa is trying to turn her life around. She has Wearside Women in Need for support and she has a job now, for the first time in a long time.

She now realises the cost of the years of her ex-partner’s controlling behaviour and she wants change. Her battle is to rebuild her life.

For Claire, there is a wider battle - to change attitudes in courts and council offices and police stations.

She will continue to fight.