Dundee's V&A Museum of Design, one of the most eye-catching public buildings of recent years, will finally open on Saturday.

It is a remarkable coup for Dundee, the small city on the east coast of Scotland, best known for the Beano and marmalade.

The V&A is the world's leading museum of art and design and has been in London for well over a century without ever branching out across the UK.

So it might seem odd for it to set up in Dundee, a city of just 150,000 people with a troubled history of industrial decline and social problems.

But Dundee insists it is on the up and embracing design and creativity.

It is a far cry from 25 years ago when the city's Timex factory shut down after one of the most acrimonious strikes of the 1990s.

It was an “army” of women that made the Timex tick.

At its height the company employed about 6,000 people in Dundee and 80% were women, who mainly worked on the assembly line putting together mechanical wristwatches.

Timex took on a highly-skilled female workforce as the once-dominant jute industry lost out to man-made fibres.

Jute, an industry that defined Dundee for years, was at the bottom end of the textile league, used for things like ropes, sacks and carpet-backing.

The Timex assembly line workforce were mainly women

Wages were relatively low and the workforce was largely female.

So much so that in the early part of the 20th Century, Dundee was often known as a “she town”.

Abertay University's Mona Bozdog has carried out research on Generation ZX

It was a place where women were the breadwinners and the unemployed men who stayed at home were “kettle boilers”, says Abertay University reseracher Mona Bozdog

In the Timex boom years, thousands of women worked on the watch-making production line but they continued the traditions of the jute mill by organising social clubs and outings.

There are tales of women being able to arrange everything from a haircut to the week's meat delivery all from their seat at the assembly line.

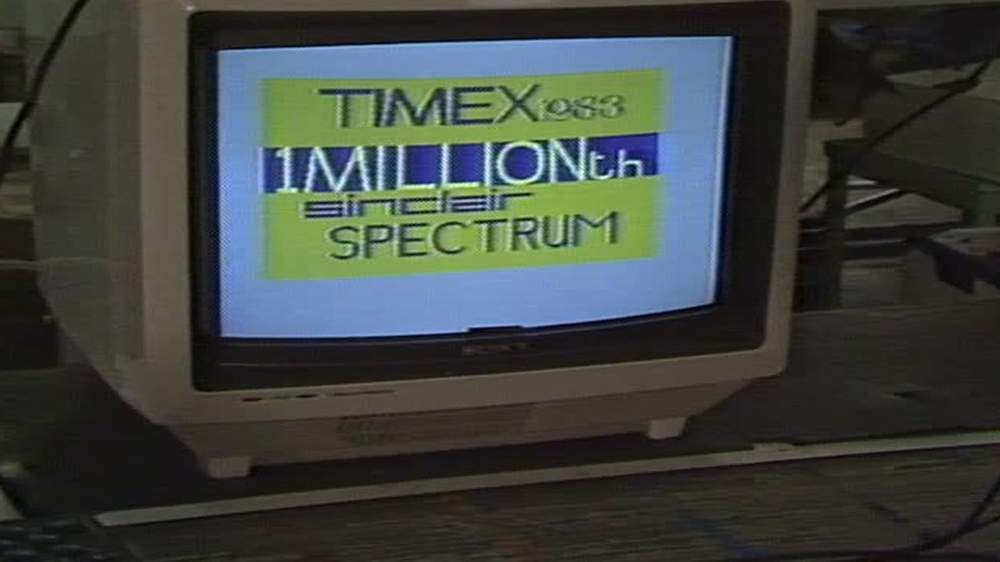

Timex made watches for decades before moving into computers

Bozdog calls it “playfulness”, a rebellious resistance to the boredom and regimentation of the work.

“That's why Timex was amazing,” Bozdog says.

“I can visualise thousands of women, all in their uniforms, walking up Timex Brae every morning and hearing their heels and the chatter.”

But by the early 1990s there were only a few hundred workers left at Timex.

Watch-making had stopped a decade earlier and at the time of the final dispute the workers were relying on making printed circuit boards for IBM computers.

But a drop in demand led to the bosses planning to lay-off 130 staff just before Christmas in 1992.

The workers came out on strike.

The strikers were mainly women but thousands of activists and supporters turned up from all over the UK to fight their cause.

So it was that Timex's Harrison Road factory became the scene of some of the most bitter picket-line protests since the miners' strike a decade earlier.

The dispute was played out in front of the TV cameras and attracted attention from around the world.

The women walked out in January but they were planning to go back when they found themselves locked out of the factory.

They were told they needed to accept a wage cut, reduced union representation and an end to a range of benefits.

When they refused, all 343 striking workers were sacked.

Timex brought in replacement workers through the picket line

The dispute got even uglier when Timex began to bus in replacement workers.

For the next six months there were angry scenes outside the factory as protesters clashed with police.

MPs and others accused militant activists of 'rent-a-mob' tactics as supporters were bussed in to join the picket.

The dispute ended suddenly in August 1993 when the management announced the immediate final closure of the factory.

It brought to an end 47 years of Timex in Dundee.

The highly-skilled workforce had shrunk throughout the 1970s as tastes in watches changed and in the early 1980s it diversified.

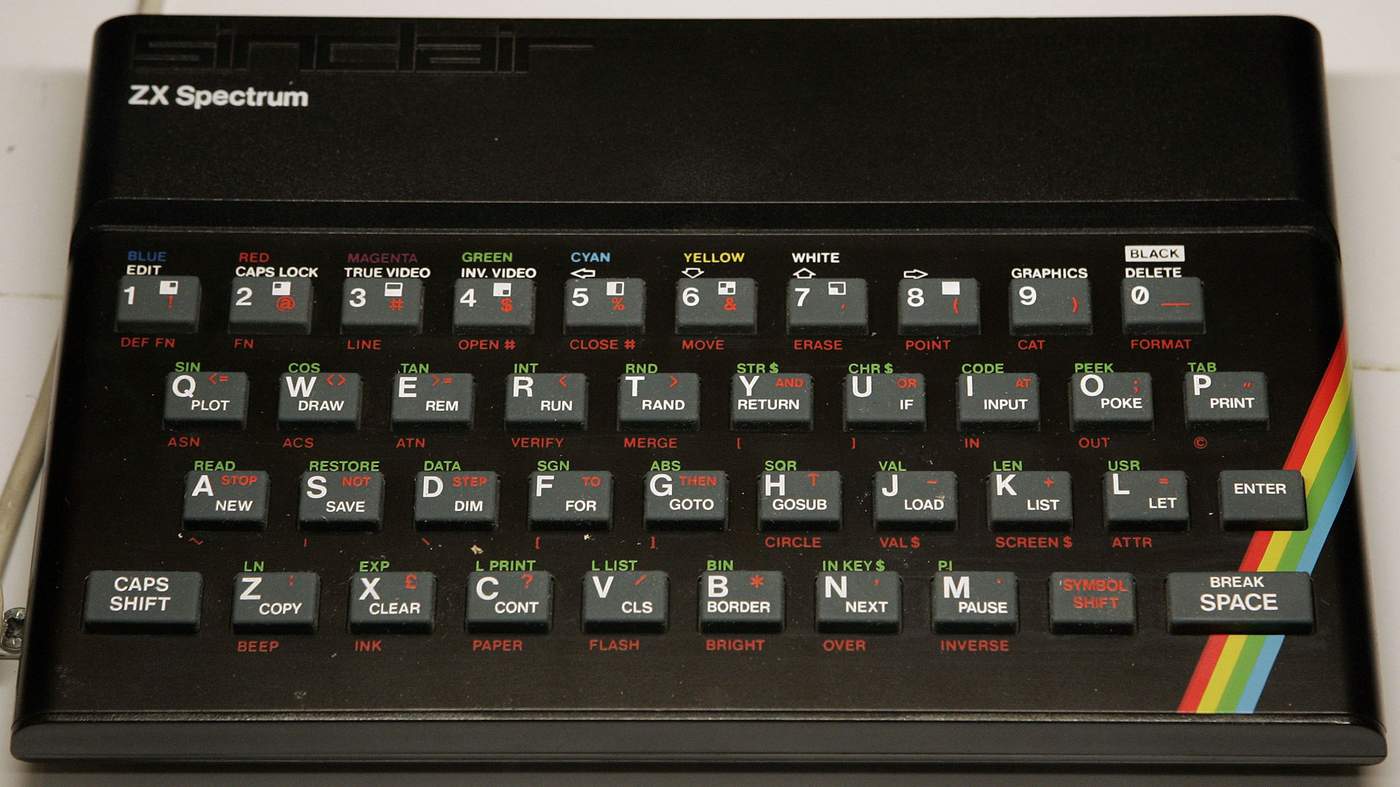

This ushered in a brief era when Timex played a major role in bringing the home computer to the mass market in the UK.

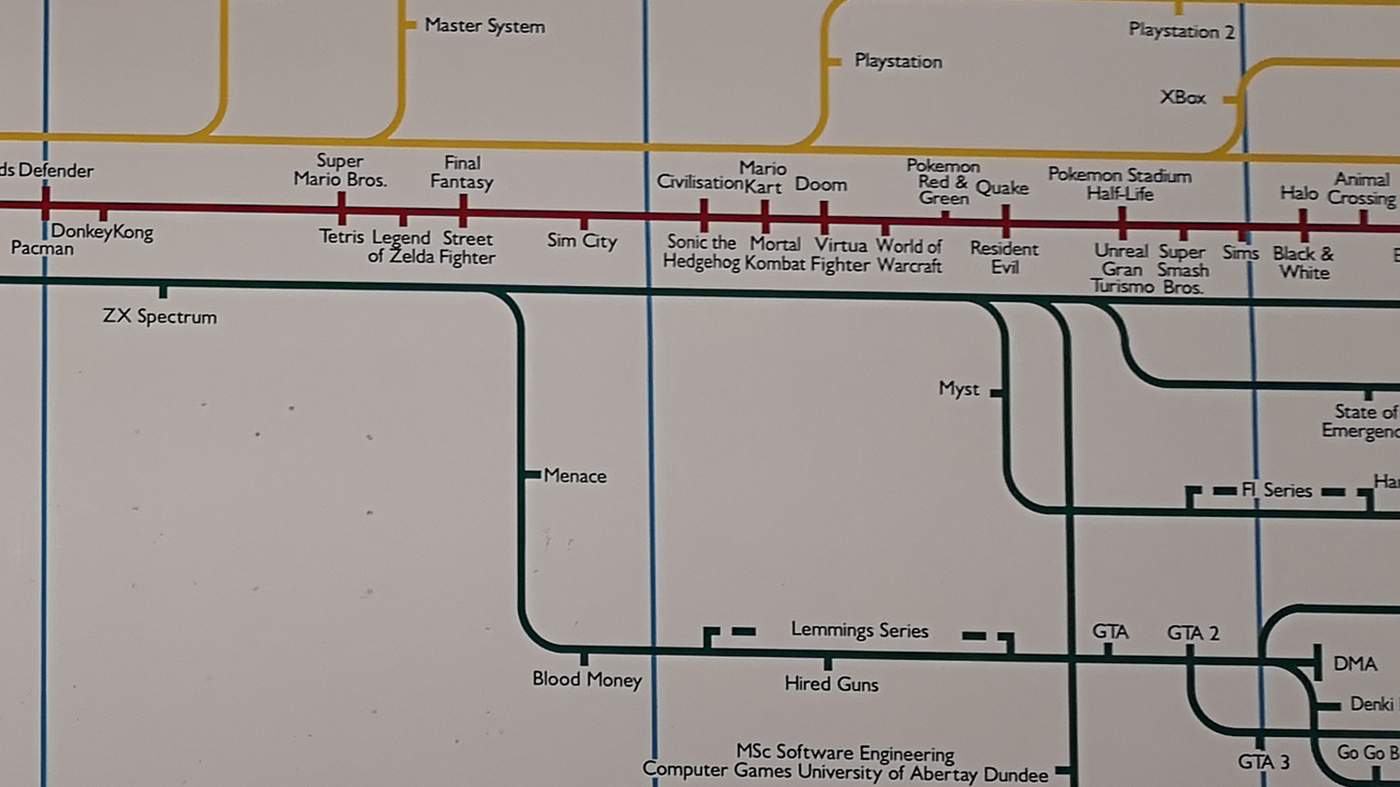

It inspired a generation of youngsters, especially in Dundee, and laid the foundation for a new industry in the city - computer games.

Twenty years ago, another unloved coastal city was suffering economically as its traditional industries disappeared.

Bilbao was also still under the shadow of years of conflict from groups such as the Basque separatist organisation ETA.

It gambled on a landmark waterfront redevelopment and transformed its fortunes.

Inaki Esteban, a reporter with El Correo newspaper in Bilbao, says there was originally opposition to a North American architect building the “foreign” Guggenheim museum in Northern Spain.

But Frank Gehry created one of the great buildings of the 20th Century and an equal of Frank Lloyd Wright’s original Guggenheim in New York.

The Guggenheim has become a focal point for celebrations

It was his decision to place the titanium-clad building alongside the river on the site of a former shipyard.

Esteban says: “It changed the Basque country image. It changed the city's image.

“We became an international city within a couple of months.

“The feeling of the people changed because the success was immediate.”

The Guggenheim in Bilbao has changed the city

He says: “The Guggenheim became a symbol for the regeneration of the city and for the regeneration of the soul of the city also, because we were in a depression.

“The Guggenheim changed all that.

“It became a venue for the city, for weddings, for festivals and for meeting people.

“It was a social place rather than a museum.”

Dundee is hoping for a similar effect.

Dundee has one of the UK's top art schools in the Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design.

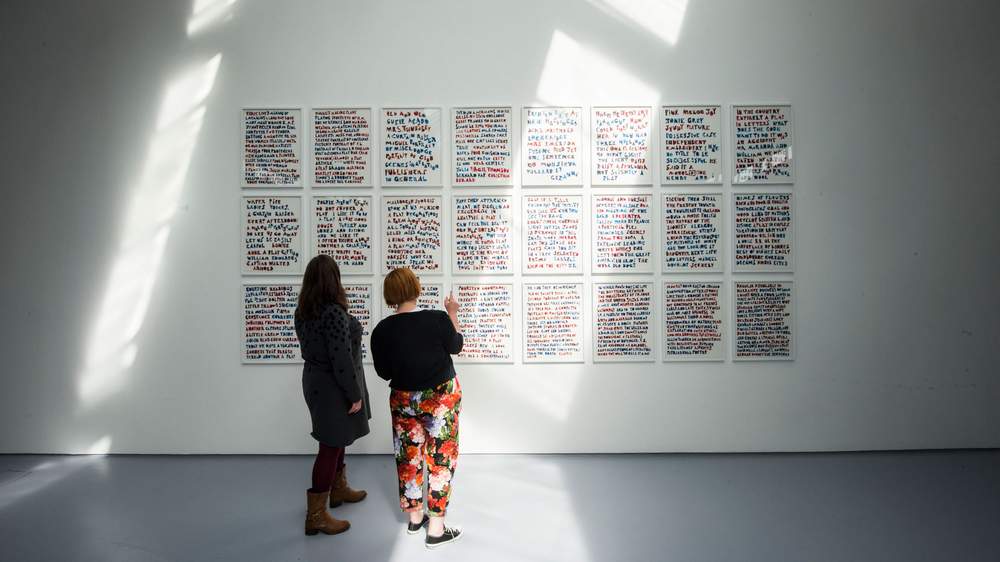

Dundee Contemporary Arts was opened in 1999

And in 1999, Dundee took its first step in making the arts central to the life of the city by opening the DCA (Dundee Contemporary Arts).

Next came the waterfront and the plan to regenerate it, with art and design at its heart.

But quite how Dundee got the V&A is hard to pin down.

There was no competition, no bidding process or shortlist.

Philip Long, the director of V&A Dundee, says the process was “much more organic than that”.

“There was a masterplan for the waterfront but it needed a 'spark',” according to Mike Galloway, director of planning at Dundee City Council.

“A plan involving a museum of design began to take shape, and the V&A saw something in it they liked and wanted to be a part of.”

The V&A is part of a huge waterfront development

The city already had links to the V&A through Duncan of Jordanstone and this helped bring it on board.

But Philip Long insists that the city chose the V&A not the other way round.

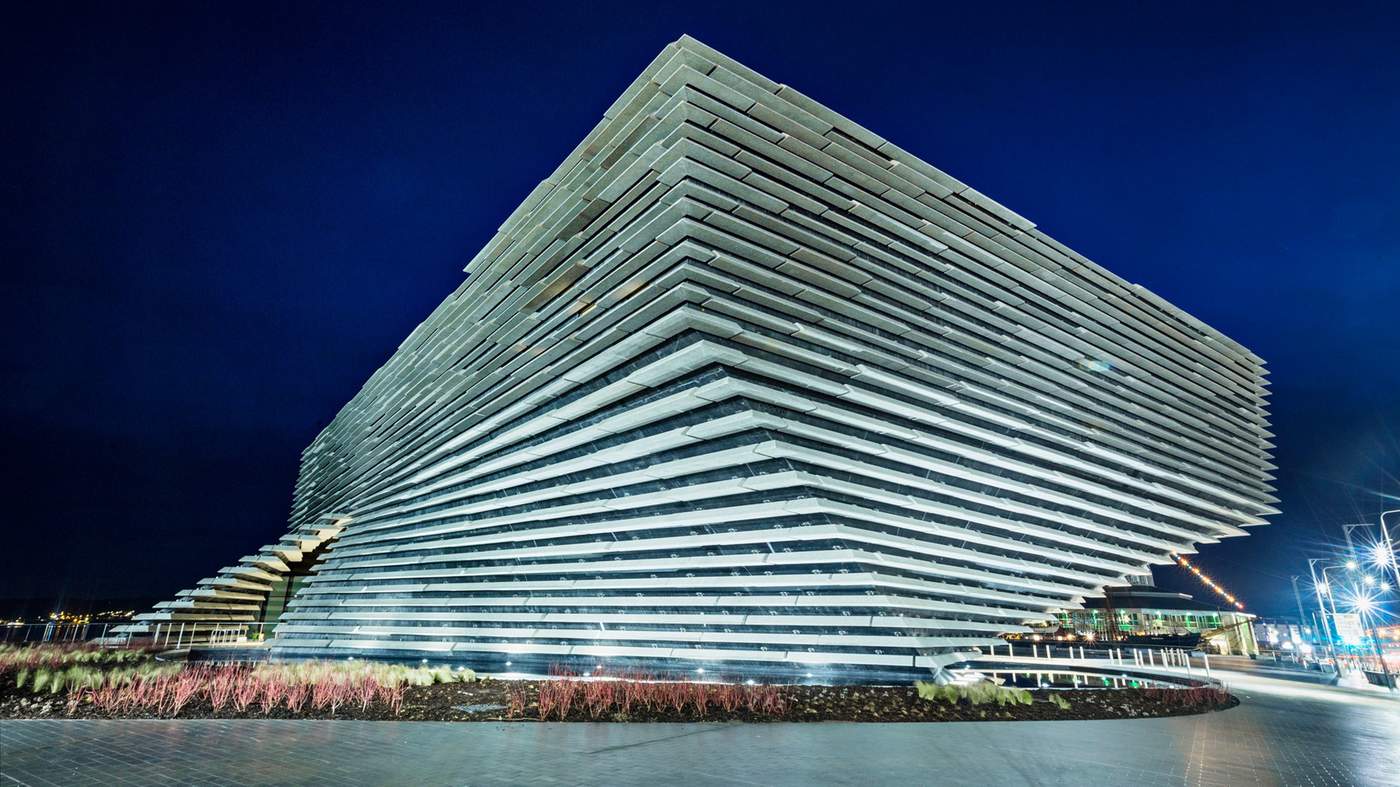

Kengo Kuma's design proved expensive to build

The original budget for the museum was half its eventual £80m but Japanese architect Kengo Kuma's design proved costly to bring to life.

The museum has been built out into the River Tay, with a 'prow' jutting over the water like a boat, recalling the shipbuilding heritage of the city.

The 63-year-old architect has also designed the New National Stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics but this is his first building in the UK.

The V&A juts into the water like the prow of a ship

Kuma says the big idea was “to create a new living room for the city”.

The architect says the form of the museum was inspired by the cliffs on Scotland's north-eastern coastline.

The effect was achieved by cladding it in lines of pre-cast reconstituted stone panels that run horizontally around the curving concrete walls.

The 2,466 stone panels, which were made in moulds, weigh up to 3,000kg each and span up to 4m.

Dundonian writer AL Kennedy says: “It is the most successful grey I have seen in Dundee.”

Inside the museum, the Scottish design galleries are filled with more than 300 pieces brought north from the V&A in London as well as borrowed from other collections across Scotland.

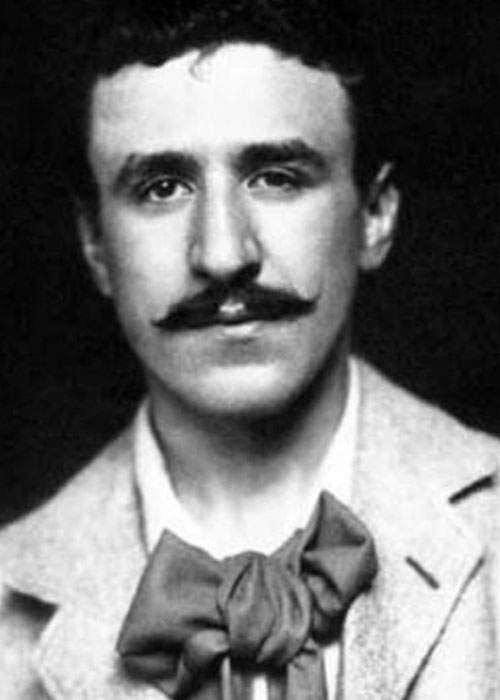

The main feature will be Scottish designer Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Oak Room, which has not been seen in public for almost 50 years.

It was saved from demolition in 1971 and has been kept in a council storage unit ever since.

Charles Rennie Mackintosh is one of Scotland's most famous designers and architects

The restored Oak Room is given new heart-breaking prominence after Glasgow School of Art, Mackintosh's finest creation, was destroyed by fire in June.

While the art school is seen by experts as his finest achievement, many of the public view his tearooms as the place that defined the Mackintosh style.

The Oak Room was designed in 1907, when Mackintosh was at the height of his career and planning the final stages of his art school project.

It is the largest interior designed for Miss Cranston's Ingram Street tearoom.

But fashions changed and it was not used as a tearoom after the 1950s.

In 1971, the building was knocked down to make way for a hotel but the Oak Room was saved.

Each section was recorded and referenced before it was put in storage.

Plans and elevations of the rooms were drawn to show how everything fitted together.

However, it still took a major restoration effort to get it fit for display in the V&A.

A diamond-winged Cartier tiara will be one of the items on display

The museum's Philip Long says he hopes the design galleries will be a “revelation”.

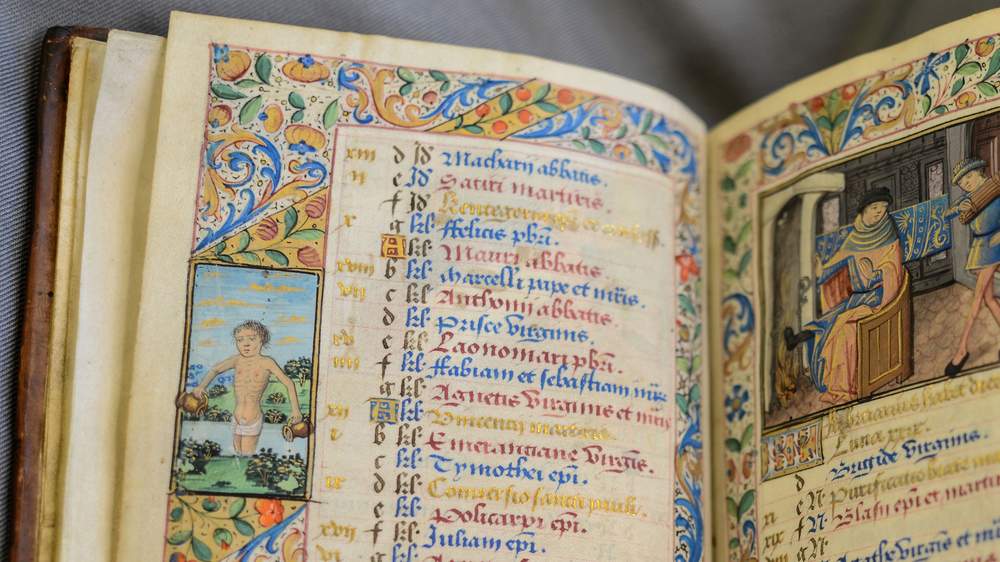

Wellies, tiaras, a copy of the Beano and a 15th Century illuminated manuscript are among the items on display.

A decorated 15th Century Book of Hours is one of the items in the museum

But perhaps the most important work of art is the building itself.

There is no doubt that the new V&A has brought a buzz to the place that brands itself “the city of discovery”.

Inside Spex Pistols, an independent store dedicated to all things eyewear, there is a mirror connected to a cloud-based facial recognition service.

It guesses your age and tries to play songs from when you were 14.

The mirror was developed with Dundee University and has been exhibited in the V&A in London.

The shop's owner, Richard Cook, says Dundee has always been a destination of interest for design-minded people.

He says: “There has always been a strong artistic culture woven through the fabric of Dundee.”

Richard thinks the arrival of the V&A is definitely positive for the city.

“There are hundreds of people who will say that they will be left out or that it’s not for them.

“But most people will at least be able to experience the renaissance feeling in Dundee.”

He says he's already seeing a big rise in tourists coming into his shop.

“It’s a beautiful city, in a lovely part of the world, but until now, we’ve been a world class secret.”

On the one hand, there is a genuine and positive mood in the city about the V&A and the global spotlight it has created.

However, Dundee has one of the highest drug death rates in Europe.

Per head of population, more people die from drug overdoses in Dundee than any other city in the UK.

Last year there were 57 drug deaths, one for every 2,600 people in the city. And the rate has been high for the past five years.

Dave Barrie works in drug rehabilitation

This is the “real dichotomy” in Dundee at the moment, according to Dave Barrie, who works for drug rehabilitation charity Addaction.

It is a devastating and real tragedy for Scotland.”

He says: “We are losing on average more than one person a week through fatal overdose and that’s a real person that’s lived a life and has a family.”

But Dundee is not alone, he says.

Places like Glasgow and Fife are also seeing a large rise and almost 1,000 people die of drugs each year in Scotland.

He links the problem to years of poverty, unemployment and lack of hope.

Along with Glasgow, Dundee was the council area with the lowest levels of employment (65.4%) last year.

However, Barrie is hopeful that the excitement and creativity in the city can help change its future.

“There is a real positive buzz and we are trying to replicate that within the recovery community,” he says.

“There is a lot of really good work going on.”

He says the global spotlight can be used to benefit the city.

“Dundee needs to become a city of recovery.”

Dundee - cool, fashionable and a hot tourist destination?

“Is this some bizarre joke?” Dundonian writer, academic and stand-up comedian AL Kennedy told the BBC radio documentary Designing Dundee.

As someone who grew up in Dundee in the 1960s and 70s she finds it hard to believe people around the world are taking notice of the city.

She says Dundee is “historically beset by ugliness and brutalism”.

“And the things we see every day tell us whether we matter, whether we are loved, have power,” she says.

Kennedy says the arts can act “like rocket fuel” and be the key to all kinds of freedom for marginalised people.

Could it actually be that the V&A - a piece of art containing other art - might be about to provide fuel and freedom for a whole city.”

V&A Dundee director Philip Long hopes so.

He says: “One of the things I hope it can do is to help Dundee find its voice and be proud of its achievements.”