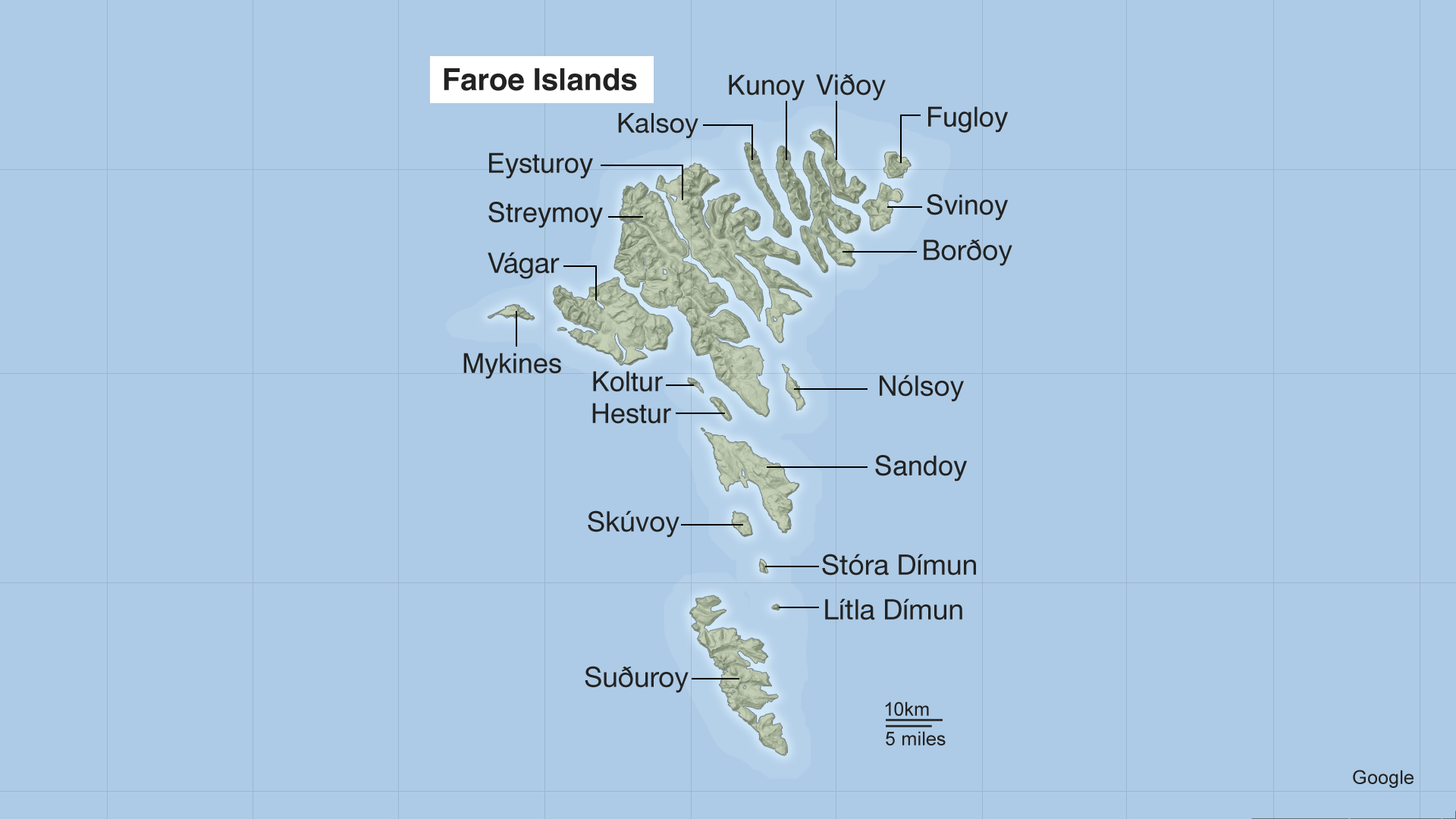

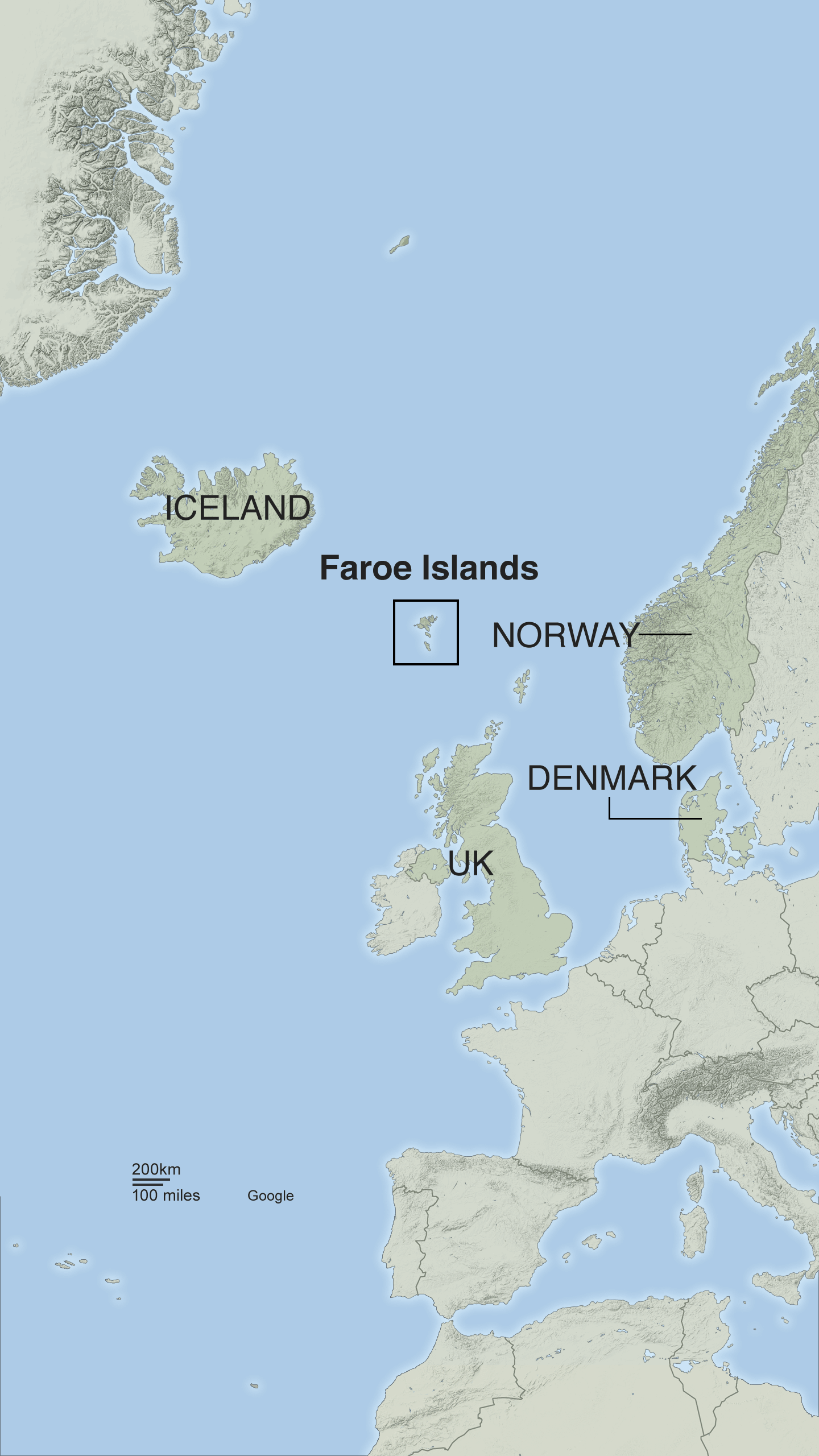

When it comes to remote, the Faroe Islands has it all.

Tucked between Norway and Iceland, in the dark waters of the North Atlantic, the 18 tiny islands are home to a population of just over 50,000.

Half of those residents live in the archipelago's capital Tórshavn “Thor's harbour”. But some of the islands are sparsely populated, with just a handful of people living on them.

The Faroese are self-reliant, modest people, with a rich heritage of storytelling and a deep desire to share information with one another.

The self-governing nation has a well-developed communication network - courtesy of the Kingdom of Denmark of which it is part - but many still rely on the postal service.

Some of the islands are connected by tunnels and bridges, but on others, mail bags arrive by boat or even helicopter.

A network of hard-working postal workers then criss-cross islands on old mountain routes used since the 19th Century delivering the post.

The fittest people used to be nominated to walk these routes, but these days 4x4 postal vehicles cross the rugged terrain.

But still, on the smaller islands, post is delivered on foot by locals. Meet some of them.

She will soon retire and pass on most of the responsibility to her brother Bjarni.

It’s winter on the Faroe Islands and an icy wind blows.

Jancy meets the helicopter that brings the island's post wearing a floral headscarf, simple jacket and short wellingtons. She doesn’t wear gloves, despite the freezing wind coming off the ocean.

She says she’s never cold.

In summer the island is served by boat, and the mail arrives in brown hessian sacks. But in the winter, it’s too dangerous to sail.

Most of the islanders gather at the helipad when the helicopter arrives - this is a big moment in the day.

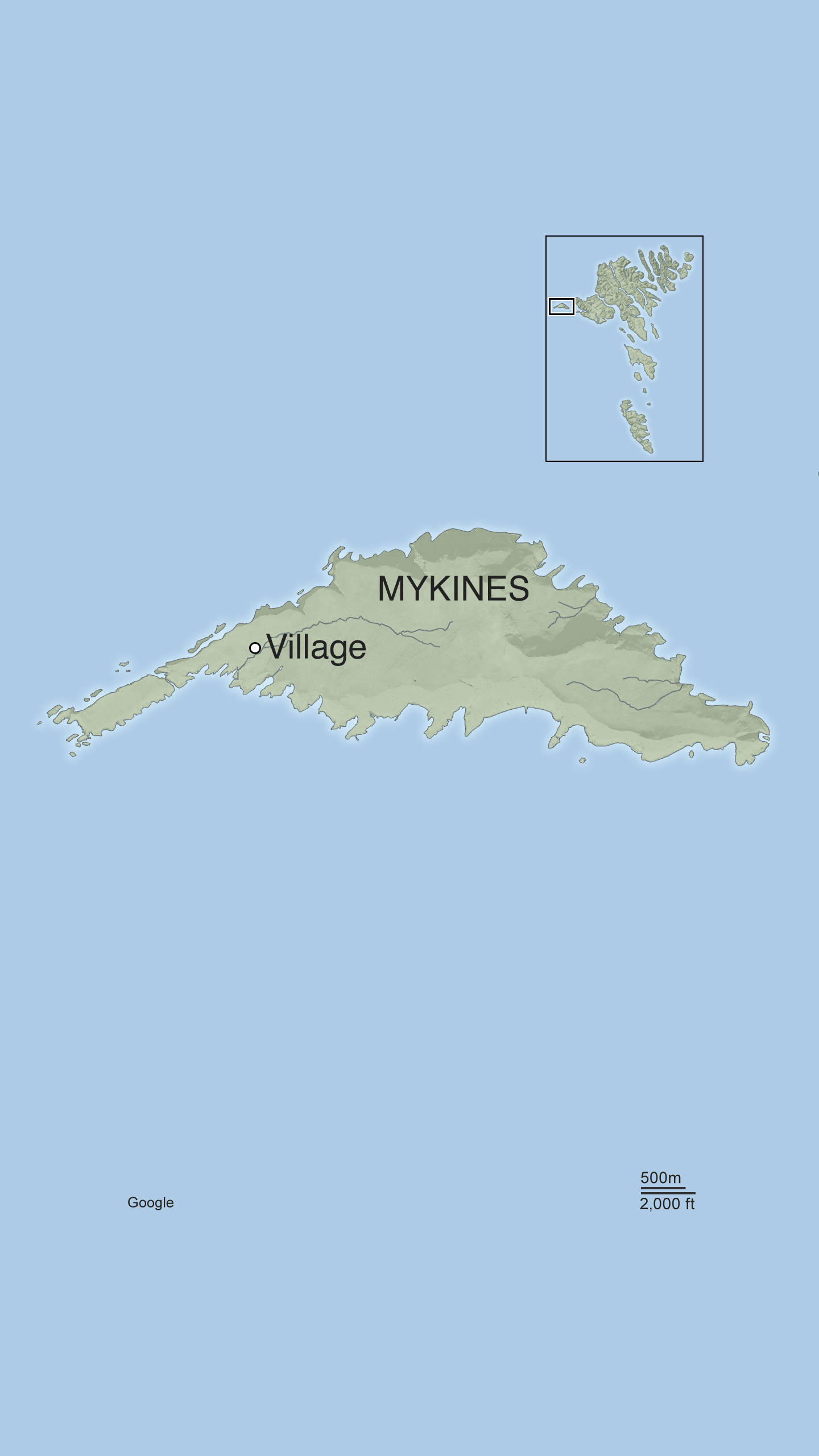

Sheep graze high up on the slopes, and seabirds - most famously puffins - nest all along the island’s westerly tip.

Jancy’s canvas shoulder bag often carries copies of the Faroe Islands’ two daily newspapers - both of which have loyal readerships and connect many of the islands’ older residents to the issues of the day.

There are currently no children living on Mykines. Two young people left the island recently. One went to study physics abroad and the other went to study in a Faroese town on what's known as the mainland - the largest islands in the archipelago, all connected by road tunnels and bridges.

Jancy’s daughter is in her 30s and lives in Copenhagen where she works as a vet. “She'll never move home,” says the post woman. “I understand. I like Copenhagen, you can be anonymous - unlike here.”

The residents of Mykines visit their neighbours every day. Doors are never locked - there’s no crime - and visitors are always welcome. In summer, tourists arrive - mostly to view the seabirds.

Flasks of black coffee and tins of old-fashioned chocolates sit on plastic-covered tables in every home, ready to welcome visitors.

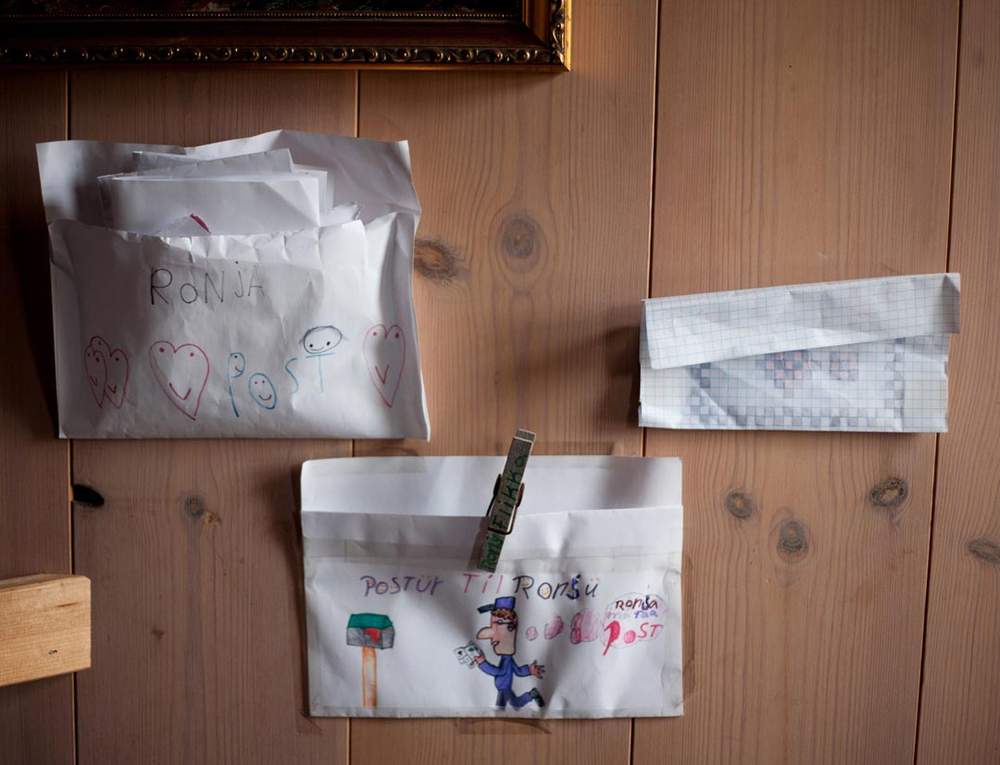

Kristina runs a small guesthouse on the island. She tells me how her children, the last to leave the island, “kept the postal service in business” with their eBay and Amazon purchases.

Ordering parcels worth less than 300 Danish Kroner (£35) means residents can avoid heavy taxes - so across the islands, young people order lots of individual items.

Internet shopping keeps them connected to the fashions of the outside world.

Kristina tells me how she would always mail order clothes for herself and the children from shops in Denmark.

She felt it gave them an identity that was far away from their island home.

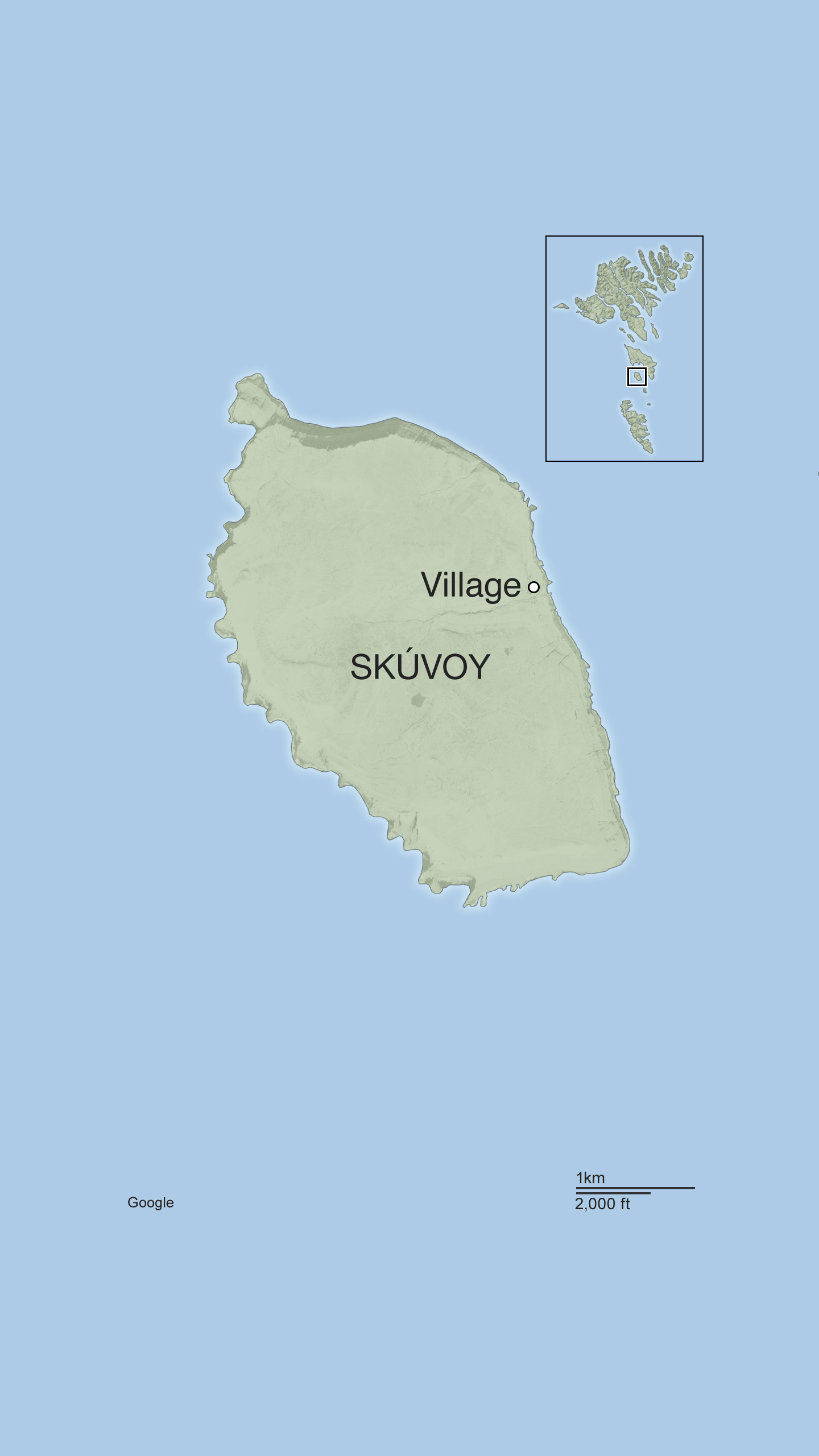

Meinhard and his wife Jessie are among the island’s 22 permanent residents.

Skúvoy is famed for its North Atlantic bird population, and local men hunt for Fulmar eggs on the high cliffs in the summer.

Before taking over from his father, Meinhard worked as a fisherman. In the 1960s, it was typical for the Faroese boats to fish around Scotland and it was there that he met Jessie, a native of the island of Lewis.

The couple married and opened the island’s supermarket.

Meinhard took over as a postman in 1975 - a job his father had started in 1938.

Today, the mail boat or helicopter arrives on the island three times a week.

Meinhard has rarely taken a holiday. Occasionally he travels to the mainland to spend time with the couple's eight grandchildren.

Dogs on Skúvoy roam the lanes freely, including Meinhard’s 13-year-old Rolf, who follows him on his postal round.

The boat to Skúvoy is relatively new.

Light and fast, it was built in Denmark and then sent to Spain to take workers to their jobs.

On a previous visit, I travelled to the island on an older, smaller ferry. Strapped to its deck was a shiny white coffin. It would be delivered to the home of Gretur, a local sailor and fisherman who had recently passed away.

The crossing is always bumpy as currents merge. The boat is the link to the island’s survival, connecting Skúvoy to the nearby island of Sandoy.

Soon Sandoy will be connected to another larger island by a tunnel, and it’s hoped this will encourage more people to start a life there.

There is also talk of a tunnel being built to Skúvoy, but islands with tiny populations are unlikely to attract this kind of investment.

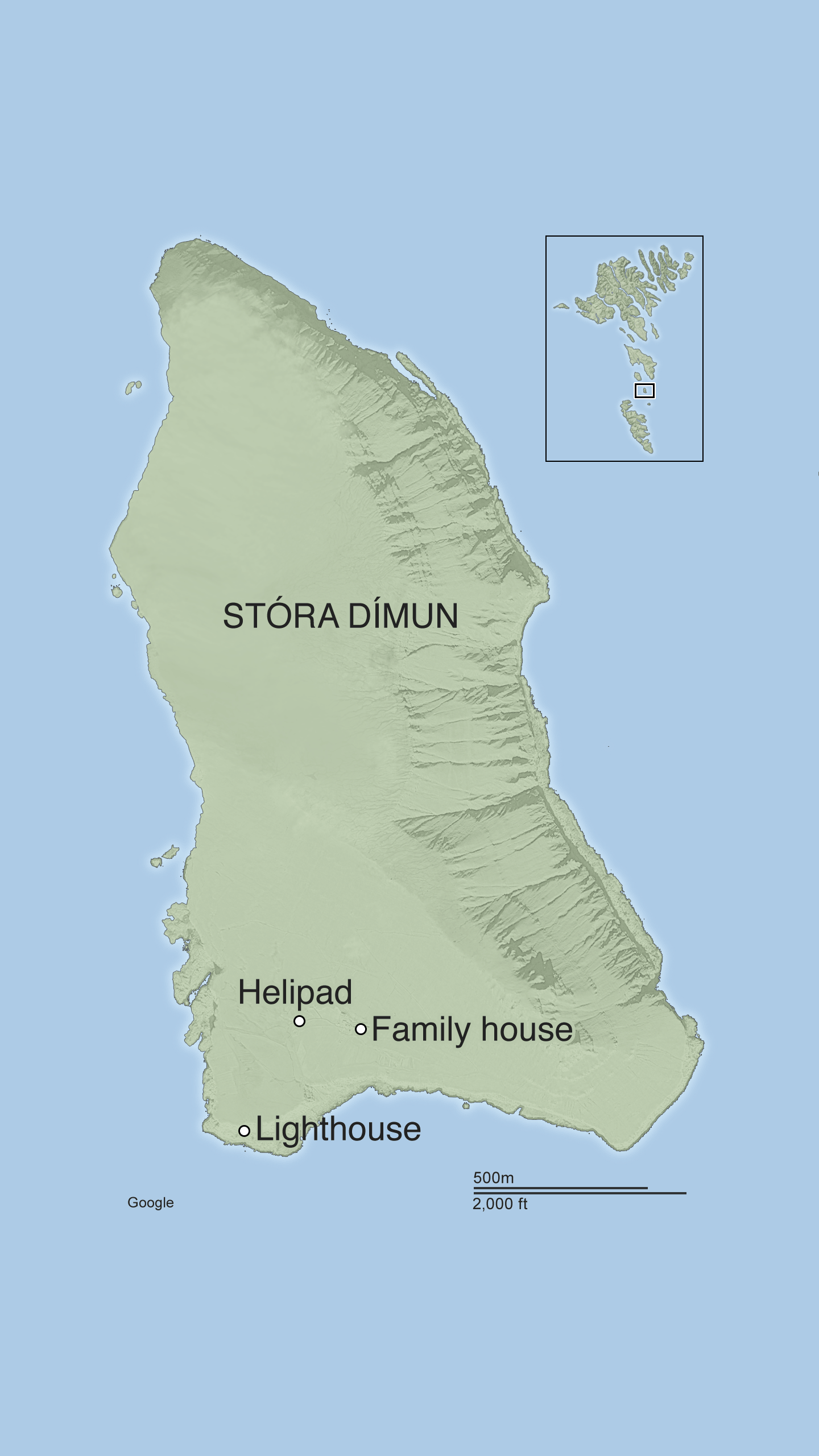

Stóra Dímun can’t be reached from the sea without climbing a cliff face, so the only way on to the island in winter is by helicopter.

At one end is a steep, wind-battered peak on which sits the island’s lighthouse. At the other, is a steep, curving hillside populated by hardy sheep.

This glaciated slope curves up to a narrow plateau at the top where Icelandic horses graze.

The white Atlantic Airways helicopter named Ruth, after a famous Faroese painter, turns to make her descent on to Stóra Dímun.

A woman sits in the helicopter wearing thick, padded farmer’s overalls and low-cut wellington boots. Wiry with brown hair tied back, this is Eva.

She helps unload the provisions from the back of the helicopter and she is greeted by her niece Andrea.

The arrival of the helicopter is a big event and the only contact the families have with the rest of the world.

Everyone is there to watch.

From outside, the houses and farm have the appearance of a fort, protecting its inhabitants from the elements.

Inside, a lunch of wind-dried lamb, boiled eggs, cow tongue, thinly sliced cured halibut, and rhubarb jam has been prepared.

The family squash on to long wooden benches in the low-roofed room and a conversation on Faroese politics begins.

On the previous day, a Danish academic was secretly filmed by a Spanish journalist saying how much the Faroese were dependent on Denmark.

Not long before this, the Danish government flew an incorrect version of the Faroese flag in Copenhagen.

Erla, a mother to three children and wife of Janus, says how this attitude towards the Faroese from the Danish authorities upsets her.

This is a family trying to survive on this island, blending old and new.

There are reminders of tradition around the house. Above the dining table hang amber-coloured transparent ellipses.

They are dried sheep’s bladders, which the children sell at small markets elsewhere in the Faroes.

Both Janus and Eva's families are entrepreneurial and full of energy.

Their plan is to make cider or an aquavit spirit with the turnips in partnership with a Faroese brewer.

The farm buildings are covered by solar panels, utilising the exposed setting.

The children Óla Jákup, Andrea and Tórur are schooled on the island in a specially built, traditional grass-roofed cottage that doubles as a house where visitors to the island can stay.

The teachers are often young graduates or early in their teaching careers, looking for a new experience. A rota ensures the children see different teachers regularly and this is working well.

The children are also connected to corresponding classes in the school on the mainland via the Internet.

This allows them to see their “classmates”. Friends and pupils come to stay on Stóra Dímun via helicopter.

The post and the helicopter are essential to life on the island.

Oil is flown in drums, hung like a trawler’s net full of fish below the helicopter.

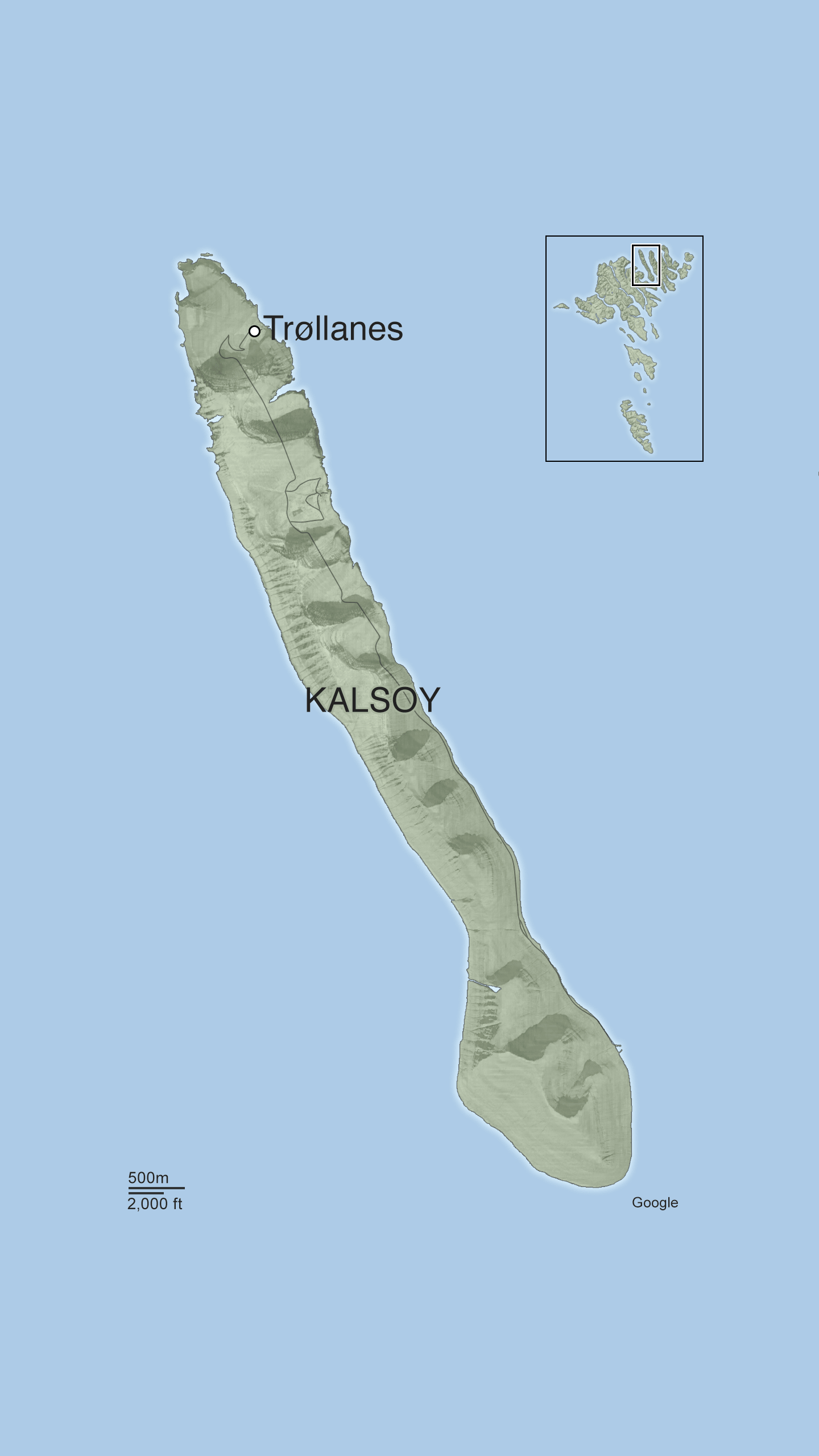

He lives with his wife and their three grown-up children in a village called Trøllanes on the most northerly tip of the island.

The village sits in a hollow, smoothly rounded by glacial ice.

To get to the village you must drive through a narrow one-way tunnel with no lighting. Before it was built in the 1970s the village could only be accessed by boat.

Fewer than 20 people live in Trøllanes - which when translated into English means Troll peninsula. The "troll" relates to humanoid creatures from folklore and mythology.

Eyðun’s mother was born in the nearby village of Mikladalur, home to the Faroese legend of the seal woman, or selkie. The whole island of Kalsoy has this folkloric significance.

Eyðun is the renaissance man of the island, having lived away and studied before returning to make a home in the village.

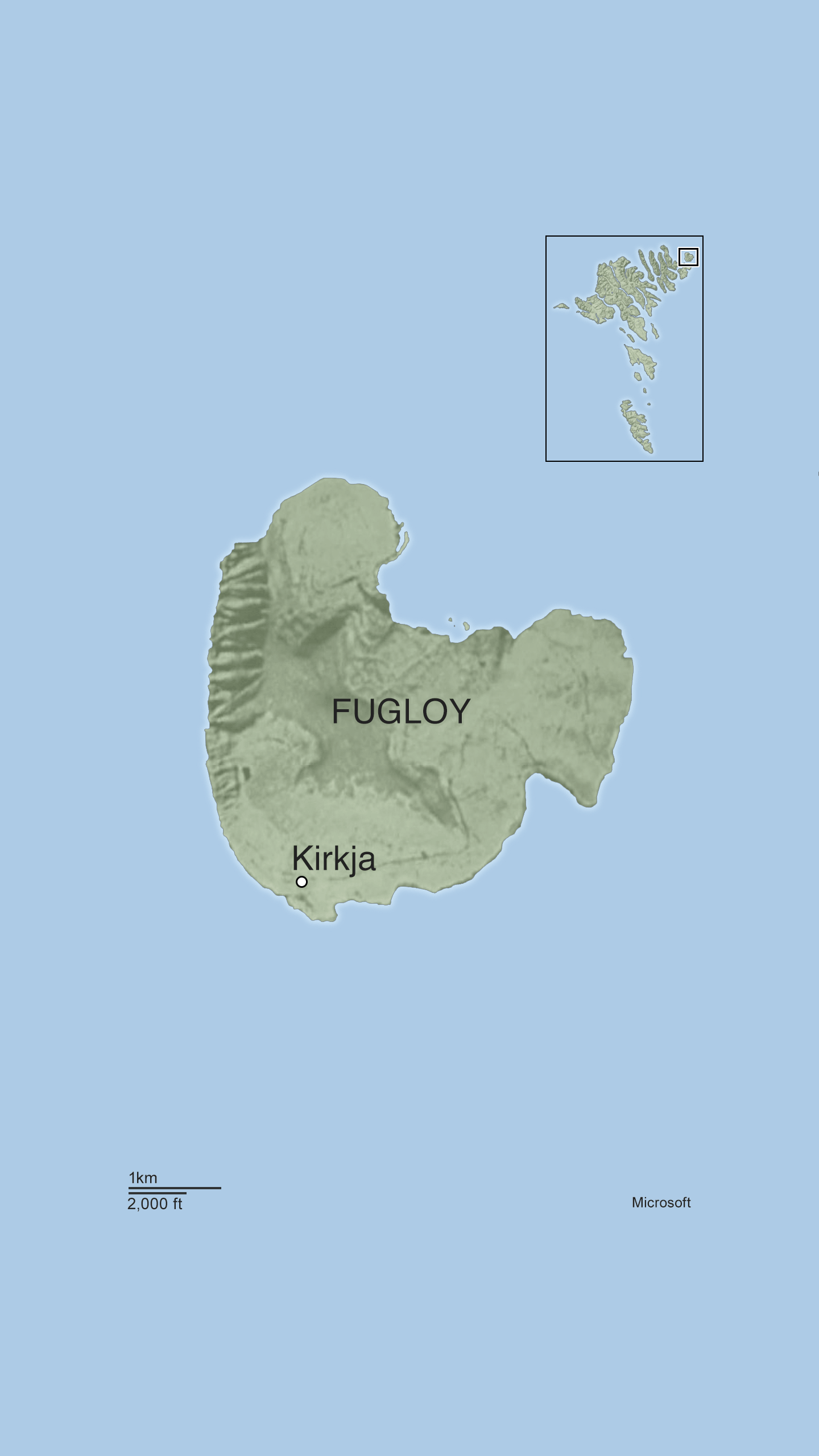

The ferry to Fugloy brings the post from Hvannasund, a village in a fjord between the islands of Borðoy and Viðoy.

It was winter when I visited and there was an icy breeze. The boat’s cargo was light - a postal sack and a box filled with about 50 light bulbs. The bulbs had been used at a party to illuminate a community house, a deckhand said.

Below deck, a worn Bible lay on a shelf at the waterline, the front cover missing. Two bubblegum machines with globe-like tops were chained to the stairs leading to the deck. Their colourful sweets rolled around with the swell. I was the only passenger.

It grew colder as the boat left the fjord for open water and her destination of Fugloy.

Arriving at the island, the swell was high at the village of Kirkja. The boat couldn’t dock and so deliveries had to be thrown towards the harbour, where postman Joannes was waiting.

In the family home Svanhild his daughter is sitting at the dining table. Her forearms are covered with white emulsion paint. She’s been helping her father on the farm, painting the buildings that house the sheep during winter.

“We have four calves and we still keep sheep,” she says. “The village is shrinking. The last of the children have left and the school is empty. There are just four of us. People come and go.” Still, she is determined to make a go of it, working on the farm and helping with the helicopter duties.

All the postal workers, like Meinhard on the island of Skúvoy, have worked hard to keep the disconnected islands connected - not just with letters and parcels but also by providing a vital community link.

He hopes that new enterprising families will follow in the tradition of Faroese self-sufficiency and set up homes on his, and the other the remote islands, ensuring the postal sacks are always full.